6 minute read

THE CALIFORNIA LI'MBER MERCHANT

has this heretofore little-thought-of hardwood from the far North. They usc it for purposes that these aircraft technicians say no other wood hard or soft can begin to perforrn- The Birch going into this plane is all from Wisconsin, and from the Dominion of Canada. In the last World lVar we heard much of Spruce for aircraft. Spruce is in no less demand for aircraft now than it was then for all the uses for which it is so well fitted. But Birch and Spruce are not competitive in any way in aircraft construction. They are used in entirely different ways, for different purposes. Birch is very hard, yet workable, and possesses unapproachable strength and resistance to breakage. You can't break Birch, even the thinnest piece. You have to apply enough power to literally tear the fiber apart. The first rupture leaves something like a wooden rope that defies complete breakage. And it surfaces beautifully and smoothly, takes glue perfectly, and offers the most perfect laminating characteristics. The aircraft technicians would rather find a substitute for Birch than for almost any other material they use.

While it is reported that in those districts of the North where Birch is to be found they are using all-out efforts to produce a maximum amount of the wood, yet the supply is constantly dwarfed by the need for more and more wood of its characteristics. I'll have to tell you more later about the things they do with Birch. Suffice it to say here that this greatest of planes will be built entirely of Birch, ANd thAt it v/iII tAKC THREE MILLION FEET Of BirCh lumber to build it. The framing, the sheeting, the fuselage, the furniture, the wings, the wing coverings-all will be of Birch. And they make everything out of thin slices of this wood, not out of boards or planks. The stufr arrives about one-eighth of an inch thic\ six to eight inches wide, and in no long lengths. The second biggest building in the Hughes plant is the place where they do their Birch fabricating. Here this thin lumber comes in, and here it is glued-up, built-up, and worked to any size, or even any length, desired. They end glue these slices of wood together and make them as long as they wish. Birch strips will run the full length of the wings in that fashion. They build every piece of that great plane out of this thin Birch. Could you believe it? They build heavy framing and thin coverings, all from the same original raw material. It can be wonderfully bent and moulded in its fabricated form. rf*rF

Tell me, gentle reader, does this uncouth but enthusiastic tale of this Howard Hughes plane interest you as it does me?

I saw Birch used profusely in other aircraft plants. They mould and build it into wonderful things for planes. I saw a lot of Mahogany. Most of the gliders I saw building were covered with sliced Mahogany veneers. This famous cabinet wood also is used in quantity throughout the aircraft industry. Of the softwoods that go into aircraft, Spruce is far and away the most useful and popular wood, with Noble Fir nott, and Hemlock and Douglas Fir close behind. That's the way I sized the thing up.

(Continued on Page 10) fn these aircraft lumber yards they stack and air-dry the Spruce. They mostly kiln-dry the Hemlock, Noble Fir, and Douglas Fir. It is all bought green, and has to be seasoned in these distribution yards. Most aircraft lumber is resawn to thicknesses from one-eighth to six-quarters in thickness. Aircraft lumber in all species must be absolutely free from all defects, and straight grained from end to end. The inspectors of this lumber give most of their attention to the straightness of the grain. They inspect it very slowly, thoughtfully, thoroughly, as befits wood on whose quality the lives of our fighting men must depend. It takes several days to load a car of airplane lumber, at the very best. Sometimes it takes as much as ten days to load a car, on account of the deliberateness of inspection. The inspector feels each piece of lumber from end to end with his hands to judge the straightness of grain.

(Continued from Page 9.)

The aircraft lumber business is the most thoroughly and practically regimented part of the lumber business of the nation. I use the word regimented in no critical manner. It had to be done that way to get results. In Dayton, Ohio, the whole aircraft lumber industry is handled. They call this the Aircraft Schedule Unit. Nobody on the Pacific Coast (or anywhere else, I assume), can buy, sell, or produce aircraft lumber except through this agency. It allocates the logs to begin with. It then allocates the lumber produced from the logs. In Los Angeles there are tremendous lumber yards specializing in aircraft lumber. They are equipped with remanufacturing and drying facilities. They buy aircraft lumber in flitches and cants and small timbers from the milts of the Northwest. They have to get permits from the Aircraft Schedule Unit for every purchase. They are told how much they can buy, and of which species. This same agency tells the aircraft manufacturers how much of this lumber they can buy, and also tells them how much of each species they can buy. Everything is done through this unit, thus keeping the available supply of aircraft lumber thoughtfully and practically distributed.

The price of this aircraft lumber, cut from the most perfect parts of the most perfect logs, is interesting. It is, of course, fixed with a ceiling. The lowest price on green lumber is $90 at the mill and the highest is $690 per thousand, at the mill. To this is added freight, remanufacturing, dryrng etc., and the result is that the seasoned and prepared lumber sells from anywhere from $140 to $750 per thousand, in Los Angeles. It is interesting to note that this same price prevails for Spruce, Noble Fir, Hemlock and Douglas Fir in the same grades and items. A fact that impressed me is the difficulty of telling Spruce and ltremlock and Noble Fir apart when they are piled together. I mean just at first glance. There is great similarity. For that reason every piece comes from the mill plainly marked as to species. tfrt*

They tell me that there is just one type of lumber for war purposes made at the Northwest mills that is even higher in grade and more difficult in specifications than aircraft lumber, and that is ponton bridge lumber. (No, brother, not pontoon lumber. The pontoon is the float on which the ponton bridge is built. But the bridge itself is ponton.) There are three items of ponton bridge lumber, six by eight, four and one-half by six and one-half, and two and one-half by twelve. And the stuff has to be absolutely clear and free from defects, and even straighter of grain than the specifications for aircraft lumber. Lrmrbermen tell me that our troops training in engineering units in Southern California and Arizona will build a ponton bridge out of this stuff across the rushing Colorado River in about three hours, and have heavy trucks running over it. *r**

The more f see of the war effort, the prouder I get of lumber. The things I have recited are just samples. For example, it takes ten thousand feet of lumber-good lumber -to crate a wooden glider, and they are building these big gliders by the wholesale in the Los Angeles district, with scores of pl,ants working at nothing else. I am told that these big aircraft plants use around half a million feet of lumber-+ach-a month, for crating and boxing planes and plane parts. When they crate these babies, they take no chances. More later.

L W. McrcDoncld Hcs Three Sons

Armed Senrices

L. W. MacDonald of L. W. MacDonald Co., Los Angeles wholesale lumber firm has three sons in the country,s service. Jack is a Lieutenant in the Anti-Aircraft, stationed at Camp Haan, Calif., Robert is in the Medical Corps at Camp Barkeley, Texas, and James is in the Coast Guard, stationed at Orick, Calif.

Mcnultrctured by ASSOCIATED PtYttrOOD MIIIS

Distributed Brclusively Siacc l92l by

Navy Saluteg Wood

"You can't fight a war, much less carve out ultimate victory without wood," says Rear Admiral Clark Howell Woodward, Chief, Navy Incentive Division, in an article enumerating the services wood and wood products have performed toward victory on the Seven Seas.

The article, Wood at 'War, a Naval salute to the forest industries' contribution to the Navy's splendid performance, has been published as a small booklet, sized to fit into pay envelopes, by American Forest Products Industries, Inc., and is being distributed to forest industry firms in bulk, gratis, to be redistributed to their employees. It is hoped that this formal tribute from the Navy will stimulate woods and mill workers to redoubled efforts to step up urgently needed production. Copies may be procured on request from American Forest Products Industries, Inc., 1319 Eighteenth Street, N. W., Washington 6, D. C.

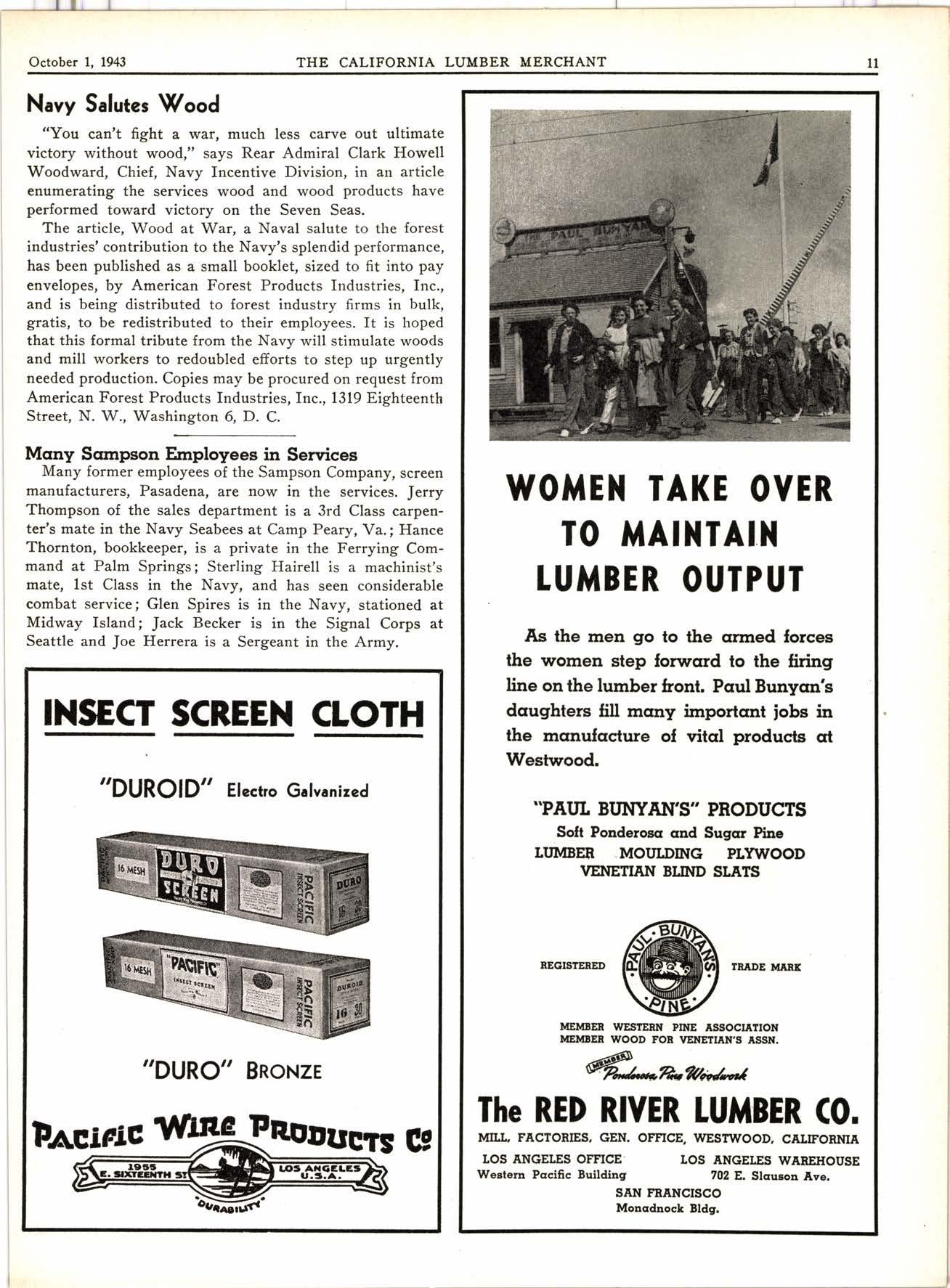

Many Scunpon Employees in Senrices

Many former employees of the Sampson Company, screen manufacturers, Pasadena, are now in the services. Jerry Thompson of the sales department is a 3rd Class carpenter's mate in the Navy Seabees at Camp Peary, Va.; Hance Thornton, bookkeeper, is a private in the Ferrying Command at Palm Springs; Sterling Hairell is a machinist's mate, lst Class in the Navy, and has seen considerable combat service; Glen Spires is in the Navy, stationed at Midway Island; Jack Becker is in the Signal Corps at Seattle and Joe Herrera is a Sergeant in the Army.