12 minute read

Reinsurance challenges

to be ready to confront Reinsurance industry needs challenges of a new decade

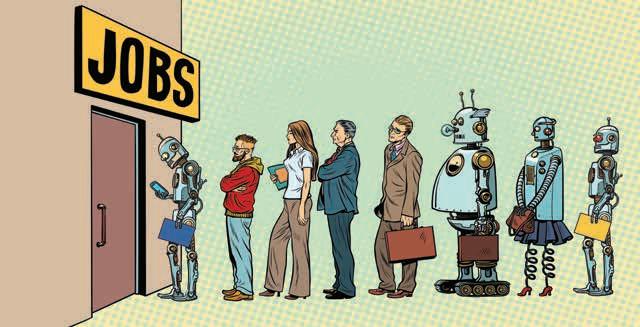

AN INABILITY to deploy new technologies and a lack of readiness to confront structural change top the list of risks facing the global reinsurance industry.

Advertisement

This comes from a biannual risk report by PwC. Entitled Reinsurance Banana Skins 2019, it reveals fears that the industry is grappling with legacy IT systems as new data sources proliferate.

Another major concern, listed as second in importance, is cyber risk, because of the unknown liabilities of underwriting cyber policies, and the threat of cyberattacks against insurance companies.

Closely linked to these worries, the report notes, is the industry’s concern around change

Ground

breaking

advances in

risk analytics

management. This reflects worries about insurance markets being upended by new technologies, and radical shifts in customer expectations.

Technology has opened-up a proliferation of data from new sources — such as sensors and Internet of Things connectivity — while ushering-in groundbreaking advances in risk analytics. The results are revolutionising risk evaluation and prevention.

The big risk for reinsurers was being left behind as the industry transforms, says Arthur Wightman, territory leader of PwC Bermuda, and insurance leader of PwC in the Caribbean. In this scenario, the front-runners recognise that talent and access to data are as important as the systems themselves in navigating change.

The inclusion of cyber risk so high on the list of banana skins reflects the accumulation of exposures and risk of unforeseen losses in portfolios on one hand, and the potential vulnerabilities

needs to

embrace

change’

within reinsurers’ digitalised operations on the other.

“Successful technological transformation isn’t just a systems issue,” Wightman says.

“It demands buy-in and upskilling throughout the organisation. The workforce needs to embrace change and see it as an opportunity.”

The third-biggest concern on the list is climate change — which received its highest-ever score. The reinsurance industry expressed anxiety about the costs of mounting claims from more frequent and more severe natural disasters, and the prospect that some risks could become uninsurable.

REGULATION RISK Rounding-out the top five is regulation risk, up from eighth place two years ago. This is largely due to concerns about a raft of new rules such as the EU General Data Protection Regulation and IFRS 17.

The remainder of the top 10 mostly focus on operating risks.

“The impact of climate change is at number three, a new entry in the top 20 and noticeably higher than for the insurance industry as a whole,” the report states.

“From floods to wildfires, the frequency of events and the severity of reinsurers’ losses are mounting as once-sporadic events become almost commonplace.

“Even greater risks lie ahead if climate change continues on its current trajectory. Through modelling of the vulnerabilities and their impact, reinsurers have a central role to play in strengthening prevention and resilience worldwide. “The industry can also bring hard numbers to the debate over how to tackle this global threat.”

Investment performance, at number six, reflects worries that low yields could encourage insurers to take greater investment risks to improve returns. Doubts were raised at number seven on the list — the industry’s ability to attract and retain talent, particularly in technical areas.

Cost reduction (up two positions to 10) and reputation risk (up five to 13) both reflect the current mood. Political risk is also rated slightly higher at number nine, with protectionism, populism and trade wars of particular concern for the

‘Even greater

risks lie ahead

if climate

change

continues on

its current

trajectory’

reinsurance industry.

“Respondents were more sanguine about the macroeconomic environment (11) and interest rates (14), which were down significantly from 2017 — although the survey was taken early in 2019 before concern around current interest rate declined,” the report notes.

In the bottom half of the table, governance risks were generally seen as under control, particularly corporate governance (18) and business practices (15) — although quality of management is more of a concern for the reinsurance industry.

The bottom cluster — including social change (18), capital availability (19), and the

Arthur Wightman

UKs departure from the EU (20) — are largely unchanged.

The survey also shows the extent to which the reinsurance industry shares risks with the broader insurance community of brokers, life companies, and other respondents.

A key difference is that the reinsurance industry places more emphasis on the threat posed by climate change. The score assigned to this banana skin (3.86) is higher than the score of any other ranked by the nonreinsurance response.

Technology and cyber risk are considered more urgent by the reinsurance industry. Regulation and investment performance are seen as slightly less worrying. IDENTIFIED RISKS The report also assesses reinsurance respondents on how prepared they feel the industry is to handle the identified risks. On a one-to-five scale (one bad, five good), they gave an average response of 3.17, which is higher than the average 2017response of 3.02.

The broader insurance industry gave an average response of 3.11 this year (up from 3.02 in 2017)..

“If we look at the top five risks as a whole,” the report notes, “what’s striking is the extent to which they feed into each other — technology is driving change management risks, for example, just as data regulation and cyber threats are heightening technology risks.

“This underlines the importance of looking at today’s fast-evolving risk landscape in the aggregate.”

more inclusive world: is this UN goal driving us towards a something we can achieve...?

BV’s JASON AGNEW takes a look at the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 1: The bid to end world poverty

INDIAN political and spiritual leader Mahatma Gandhi once said: “Poverty is the worst form of violence.”

While India has greatly reduced its levels of destitution, and much of the country would be unrecognisable to Gandhi in 2020, there are still over 70 million people living — or existing — in extreme poverty.

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were set by the United Nations' General Assembly in 2015, designed to be a “blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all”. The ambition is to achieve these goals by 2030.

SDG1 aims to “end poverty in all its forms everywhere”. Extreme poverty has been more than halved in the last 20 years — but one in 10 of the planet's population still has to survive on less than $1.25 a day.

Worldwide, the poverty rate in rural areas is 17.2 percent — more than three times higher than in urban areas, which explains the global exodus from the countryside, and the rise of the megacity.

Poverty does not just refer to a lack of income or resources; it encompasses healthcare, education, and security. Despite it being widely accepted that children constitute the majority of those living in extreme poverty, 63 percent of countries have no data specific to child poverty — and a staggering 97 percent have insufficient data to make viable projections towards Goal 1.

Having a job certainly doesn't save you from abject misery; in fact, eight per cent of the world’s

workers and their families were living in extreme poverty in 2018. So how have some of the major companies embraced these goals, not as an exercise in philanthropy but as a means of preservation for the marketplace of the future?

As the chief marketing officer of Unilever, Keith Weed, wrote in The Guardian: “The brands that have not yet caught on to this, and are not thinking about how they will embed environmental and social sustainability within their business model, will not be around in the next 50 years.”

Financial services company Visa is addressing SDG 1 by reaching out to under-served markets, to 500 million of the two billion “unbanked” adults with no or little access to financial services

Rural areas are often poorly served when it comes to the basics, such as education

because of poverty or where they live.

Electronic payments have become an important tool in helping people, especially those in rural areas, to avail themselves of such services. By empowering new consumers, a company is creating a whole new client base for itself.

The UNGSII (UN Global Sustainability Index Institute) was created to support, accelerate and monitor the implementation of the SDGs, evaluating and comparing sustainability performance of companies, cities and countries in a transparent manner.

Its Commitment Report considers the top 100 blue chip companies. Of those 100 with a combined market cap of $9.781tn, 82 disclosed their commitment to the SDGs in their 2016 annual reports. The results were not surprising: Volvo came top, Novartis second and Sainsbury third in terms of visibility, i.e. how many statements in their annual reports refer to the SDGs. US giants such as Walmart, Boeing and Apple didn’t make mention of the goals in their reports, although this is not necessarily indicative on their sustainability policies.

The problem for SDG 1 is that with such a broad, ambitious goal, it is hard for companies to know where to start. If you're a renewable energy company, your first instinct on looking at the SDGs might be to think, “Great, we are contributing to SDG 7 (clean and affordable energy) - and that's our role in the SDGs sorted”.

LOW PRIORITY GOAL Companies assume that SDG1 doesn't apply to them — and that is one of the major reasons why it is ranked as a “low-priority goal” for the business community.

The lack of specificity makes it easier for firms to identify with more narrowly focused SDGs and finding solutions for Climate Change, Gender Equality, and Reduced Inequality have been identified as the top SDG priorities for corporations.

This means that SDGs 5,10 and 13 are much easier for companies to prioritise whereas the eradication of poverty tends to be viewed as the responsibility of governments.

A good example of commitment to SDG 1 comes from Myanmar, where in 2015 the government was proposing to create a minimum wage of $2.60 a day for workers.

Garment manufacturers in the country were proposing an opt-out for their industry. But 30 European companies — including Tesco and M&S — wrote to the Myanmar government opposing the suggestion on the grounds that it would deter them from investing in the country. The government duly forced through the new base wage.

Such actions can lift thousands, even millions, out of extreme poverty, and relatively quickly at that.

The UN probably cited No Poverty as its prime objective because achieving that would lead to other sustainable development goals becoming achievable.

That, in itself, makes SDG1 an extremely worthwhile aim.

a-billion of world’s people Grim UN report shows halfstruggling to find work

ALMOST half-a-billion people around the world battle to find sufficient paid work, a UN report on employment and social trends shows.

The World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2020 (WESO) report by the UN’s International Labour Organisation (ILO) predicts that unemployment figures will rise by around 2.5m this year. Global unemployment has been roughly stable for the past nine years — but slowing economic growth means not enough new jobs are being generated.

Guy Ryder, the director-general of ILO, points to “persisting and substantial work-related inequalities and exclusion”. The trend had “profound and worrying implications for social cohesion”, he warns.

The WESO report shows that a disparity between labour supply and demand extends beyond unemployment into broader labour under-utilisation.

As well as the 188m people unemployed around the world, 165m don’t have enough paid work — and 120m have given up searching.

Inequality is higher than previously thought, especially in developing countries. Worldwide, the share of national income going to labour (rather than to other factors of production) declined from 54 percent to 51 between 2004 and 2017. That’s a greater fall than expected, and most pronounced in Europe, Central Asia and the Americas.

Moderate or extreme working poverty is expected to hamper the achievement UN Sustainable Development Goal 1 (eradicating poverty everywhere by 2030). Working poverty – earning less than $3.20 per day – affects more than 630m people: one in five of the global working population.

Other significant inequalities — defined by gender, age and geographic location — remain stubborn features of labour markets, the report says, limiting individual opportunities and general economic growth.

More than 267m people aged 15-24 are currently not in employment, education or training, and many more endure substandard working conditions. The report cautions that

The UN’s ILO says the pace and form of economic growth hampers efforts to reduce poverty

intensifying trade restrictions and protectionism could have a significant impact on employment.

The ILO found that the current pace and form of economic growth is hampering efforts to reduce poverty and improve working conditions in low-income countries. The report recommends that growth shifts in focus to encourage higher-valueadded activities through structural transformation, technological upgrading and diversification.

“We will only find a sustainable, inclusive path of development if we tackle these kinds of labour market inequalities,” says the report’s lead author, Stefan Kühn.

TEMPORARY STAFF ‘UPSKILLING PERMANENT EMPLOYEES’

THE average SME in the UK expects to spend £160,000 in 2020 to fill the skills gap in the organisation.

Research commissioned for recruitment agency Robert Half UK 2020 Salary Guide highlights the need to address the growing gap. The study found that it could cost the average UK SME £145,000 this year, rising to £318,000 in the next five years. Over two-thirds of SMEs said they planned to invest in training and development, with many looking at hiring permanent and temporary staff. The skills gap has widened as a result of macro challenges, including a shrinking talent pool (thanks Brexit), increased digitalisation and the future of work.

Digitalisation is especially concerning for UK SMEs. Half of respondents cited digital transformation as the most pressing change facing their business – with seven in 10 admitting that find qualified professionals was a challenge.

Three in five SMEs are investing more to train staff on new technologies than two years ago.

Some employers are turning to the temporary hiring market to fill the gap created by digital transformation. Three quarters of SMEs say that temporary staff have become increasingly important to managing digital transformation efforts – with 73 percent using interim employees to upskill permanent members of staff.

Matt Weston, managing director of Robert Half UK, said the skills required to thrive in today’s economy were different to those required five or 10 years ago.

“Temporary or contract staff are a vital asset for SMEs looking to navigate their way through digital transformation,” he said.