17 minute read

Plane by Day, Bus by Night (by Larry Plachno

Plane by Day, Bus by Night

by Larry Plachno

Advertisement

Photos from NBT Archives unless otherwise indicated

One of the reasons behind the development of the Pickwick Nite Coach was to transport airline passengers in comfort at night when the airlines did not fly. This example was one of a group built in later 1928 with several modifications from the original Alsacia. The most obvious change was to extend the roofline to the back of the coach as well as the different front grille and vents.

The April, 2021 issue of NATIONAL BUS TRADER contained an article on the 1917 Pickwick Packard converted bus that is now preserved at the AACAMuseum in Hershey, Pennsylvania. In that article, we mentioned a little bit about Pickwick Stages and how a major factor in developing their Nite Coach was to transport aviation passengers in comfort at night when the planes did not fly. Since then, we have received several questions from readers asking for more details on this. Hence, we decided to move ahead with this article.

While the Greyhound Scenicruiser normally ranks as the top iconic coach in the industry, I would guess that the Pickwick Nite Coach ranks in the top five. While nowhere near as successful as the Scenicruiser, the Nite Coach was not only unique but fostered the start of the integral construction method. The background behind the Nite Coach and its intended use is easily one of the more interesting stories of the early bus industry. It includes the rise of Pickwick from a single line to the largest bus company and its sale. It also includes some early aviation history and how the saying “fly by night airline” originated. Unfortunately, much of this story was impacted by Black Tuesday and the stock market crash that fostered the Great Depression.

As you probably have already guessed, much of this takes place 90 or more years ago. Your editor ended up climbing a ladder to the highest shelf in the archives to find some old aviation timetables from the 1920s. Parts of one of them will be included in this article. Our plan is to explain the background behind Pickwick Stages leading up to the development of the Nite Coach, then explain how aviation developed in the late 1920s, and finally show how the Nite Coach was intended to work with commercial aviation at that time. As we shall see, it is a great story but unfortunately does not have a happy ending.

The Pickwick Stages Saga

Pickwick Stages has an interesting history. The company started with one route and eventually grew into being the largest intercity bus operator in the United States. An emphasis on operating higher class buses prompted Pickwick to do their own bus assembly and manufacturing. Eventually, the company began moving toward aviation and building upscale buses that could be used in the aviation industry.

It all started in 1912 when Herbert L. Pattison and A. L. Hayes began running an automobile on a 155-mile route between San Diego and El Centro, California. This was two years before Greyhound would be founded in Hibbing, Minnesota in 1914. Running the route was at least a little bit of a challenge because of the primitive and unpaved roads in those early years. Credit is due to Pattison and Hayes for picking a route that had no direct rail service. The logical but round-about rail route involved going north to Los Angeles and then changing trains there and going back southeast to El Centro. The other alternative involved a difficult detour through Mexico. The company got its name from the fact that its buses originated from curbside in front of the Pickwick Theater in San Diego.

The first Pickwick Nite Coach was built in 1928 and was named Alsacia. It was built without a chassis and was a pioneer in developing integral construction. It turned out to be one-of-a-kind since following units were modified including extending the roof to the back. One of the more interesting buses built by Pickwick was the Cherokee. Completed in 1927 and built on a Pierce-Arrow chassis, it featured an upper level, a small galley and a raised driver’s area. While it operated from San Diego to San Francisco, it was never duplicated.

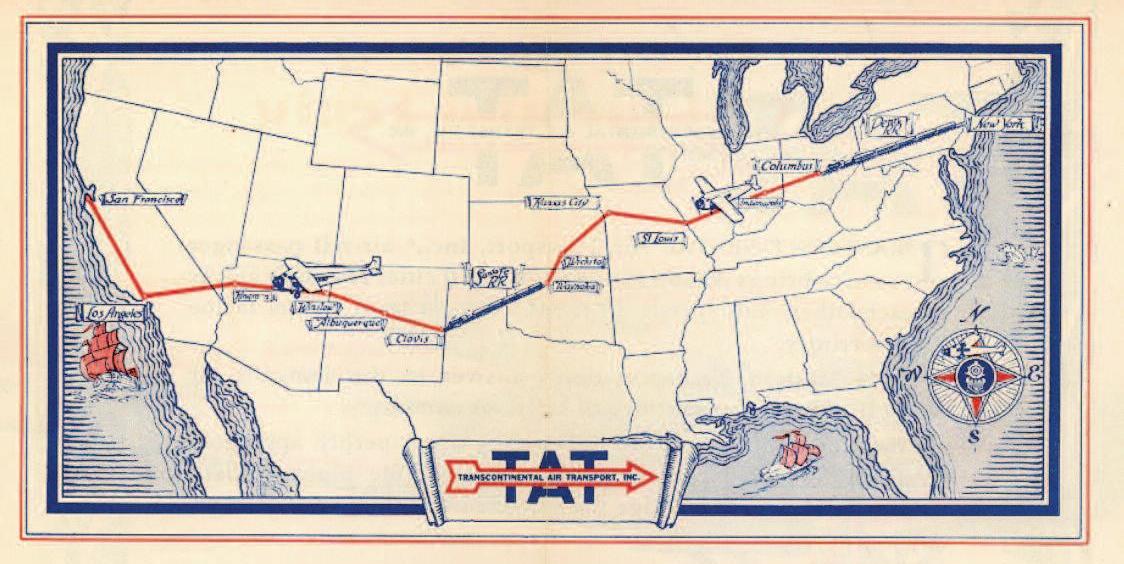

This map comes from the Transcontinental Air Transport Inc. timetable dated October 15, 1929. It provides a good idea of how the “Plane by Day, Train by Night” travel worked. Passengers rode the train overnight from New York and transferred to the plane in Cleveland. Landing in Waynoka, Oklahoma that evening, they then boarded an overnight train to Clovis, New Mexico. The last leg from there to Los Angeles was by plane.

History confirms that this original route was a wise choice and successful. It resulted in expansion in the following years that went well beyond the expectations of the founders. Asecond route was started north from San Diego via an inland route to Riverside and then into Los Angeles. Charles Wren then started a new route from Los Angeles north to Santa Barbara and eventually the 450 miles to San Francisco. This route was merged into Pickwick Stages in 1918.

What may have been a factor in Pickwick’s success was the company policy of using higher quality buses. Everything was body-on-chassis in those years. In many cases you could select your favorite chassis and your favorite bus body individually. Pickwick’s preferred choice was a stretched Pierce-Arrow car chassis with oversize radiators. In common with other big bus operations at this time, the company got into doing some of its own rebuilding and assembly work. This would eventually lead to their experience and expertise for building buses.

It was at this point that Pickwick Stages began expanding rapidly. As mentioned in the previous article, the company acquired a 1917 Packard bus with an interior converted much like a simple recreational vehicle. This was used to “scout” new routes since roads at that time could be unpaved, not well marked and often questionable. Pickwick’s bus routes reached north to Seattle in 1926, thus firmly entrenching the company on the West Coast. The company had already started expanding east.

Routes reached east to El Paso in 1926. At this point Pickwick had 2,250 route miles and 190 buses, making it the longest bus system in the United States. In 1927, the El Paso route was extended to Oklahoma City and then on to St. Louis. In St. Louis, Pickwick made a connection with Purple Swan Safety Coach, operating between Kansas City and Chicago. It was part of Motor Transit Corp.,

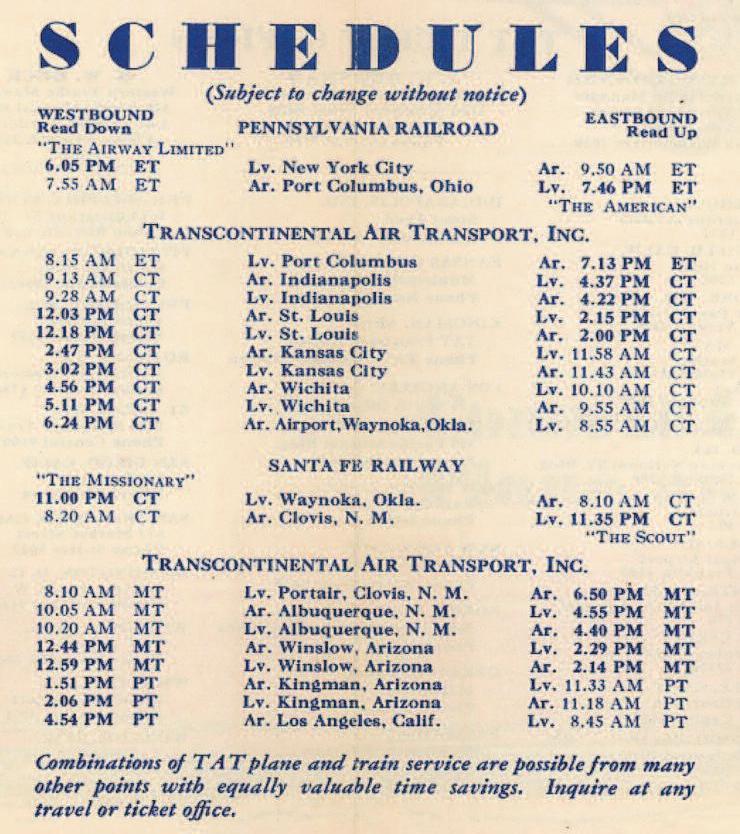

Here is the actual schedule from the Transcontinental Air Transport timetable for the plane/train combination from New York to Los Angeles. Read down on the left (Westbound) and up on the right (Eastbound). Going from New York to California in less than two days while being able to sleep at night was impressive.

This 1929 Ford Tri-Motor carries some Transcontinental Air Transport markings. With the development of the Ford Tri-Motor and similar planes in the late 1920s, aviation had reached a higher standard in aircraft. The biggest problems were weather and navigation. AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHY

BY MICHEL (HTTPS://WWW.FLICKR.COM/PEOPLE/119886413@N05).

This is the cover of the Transcontinental Air Transport timetable dated October 15, 1929. Black Tuesday and the stock market crash came only two weeks later.

the company that would become Greyhound. Motor Transit Corp. had concentrated more in the Eastern states while Pickwick was active in the Western states.

Following a 1928 agreement, Purple Swan wasrenamedPickwick-GreyhoundLines.Service was pushed east to Pittsburgh where connectionwasmadewithGreyhound’sCardinal Stages that operated to the East Coast. Hence, forthefirsttime,Pickwickcouldoffertranscontinental service. Pickwick and Greyhound were now working together and Pickwick’s bus expertise had evolved into the company looking at building buses in their Los Angeles shop for the upscale market.

Meanwhile, Up in the Air

On December 17, 1903 at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, brothers Wilbur and Orville Wright showed that heavier-than-air flight was possible. It is noteworthy that commercial aviation can point to a specific date and location as its birthplace. This is not possible with automobiles and buses because so many components and developments came on different dates in different locations. Following this, Wilbur and Orville returned to their bicycle shop in Dayton and began working on

improving their airplanes. One account relates that they would hop on an electric interurban car out of Dayton carrying a gasoline can and ride to their field to work on their planes. By 1910 there were stories about people coming to watch the planes “circulating. ”

Military interests helped aviation design progress. In 1909 the Signal Corps bought a Wright Military Flyer that goes down in history as the first military airplane. In 1911 the Navy purchased a Wright Model B and configured it to land on water. Aviation mushroomed in World War I with planes from several countries that would be a story in itself.

Although somewhat forgotten, it was the United States Post Office Department that was instrumental in developing and supporting aviation in the post-war period. On May 15, 1919, the Post Office started airmail service between New York, Philadelphia and Washington. Army pilots flew the mail for the first three months, but the Post Office hired civilian pilots and took over the operation on August 12, 1918.

In 1920, the Post Office started a 2,680mile transcontinental airmail route linking New York with San Francisco. As a preview of what would happen later, the mail flew in planes during the day and was transferred to trains at night. It took a letter 31⁄2 days to go coast to coast, which was a day quicker than by the all-rail route. This is where the phrase “fly by night” airline started; in these early days it was not safe to fly at night and in overcast conditions when the pilot could not see the ground.

In February of 1926, the Post Office started “feeder” routes from the main transcontinental airmail line. These were numbered and were operated under contract. This opened the door to commercial aviation. The earliest airline passengers often found themselves sitting in between or on top of mail sacks in an arrangement that would give a heart attack to a modern safety inspector.

In retrospect, it should be noted that by the late 1920s and the introduction of more modern aircraft such as the three-engine Ford Tri-Motor, the airplanes themselves had become relatively reliable. With the Ford Tri-Motor, airlines were able to have flight attendants serve meals and refreshments to passengers. The biggest problems facing aviation at this time were weather and navigation. It is interesting to note that these two same items were also problems for the bus industry. Unpaved roads could became a quagmire in heavy rains and the lack of major highways made routes difficult.

These early airplanes were not pressurized and hence could not fly above the weather. In addition, the pilots could not see the ground well at night or in overcast conditions. In the early days, many pilots followed railroad tracks and took advantage of the names of towns painted on the roofs of barns and buildings. Initially, light beacons were placed along the airmail routes to guide the pilots at night. Thiswasfollowedbysomeearlyradiobeacons that provided guidance at night or in overcast conditions. As a result, these early airmail routes became the first airways and were substantially improved in following years.

Much of commercial aviation that developed in the late 1920s was based on the airmail routes. One reason was that these routes offered some guidance for the pilots. A second reason is that carrying the mail provided some welcome income even if the number of passengers was limited. However, there still was some reluctance to fly at night with passengers. As an example, I will provide a map from the Transcontinental Air Transport, Inc. timetable dated October 15, 1929. Two comments are applicable. One is that Transcontinental Air Transport went on to merge with Western Air Express in 1930 as Transcontinental and Western Air that became today ’s TWA. The second is that Black Tuesday, the stock market crash that started the Great Recession, came only two weeks later on October 29, 1929.

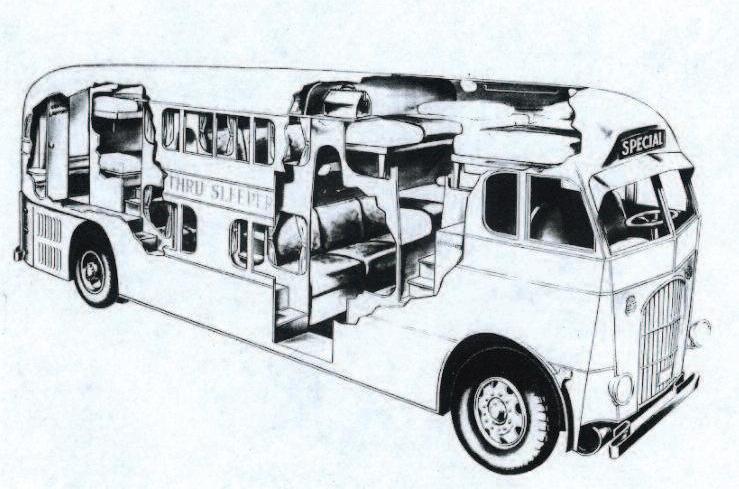

Here is a cutaway diagram showing the interior of a Pickwick Nite Coach. It was set up similar to a Pullman railroad coach with compartments that made into seats by day and berths by night. In addition to a lavatory at the rear, a chef could cook simple meals in a small galley near the entrance door. There are suggestions that Pickwick was considering leasing these buses to the airlines like Pullman leased its railroad cars to the railroads. The Pickwick Nite Coach

While the combination of flying by day and train by night looked good on paper, there were some major problems that might not be obvious. The first was scheduling. What would happen if the plane was late in arriving for its connection with the train? When the planes only carried mail, this was not a major crisis since the mail could simply be put on the next train. Passengers were a different situation. Would they be happy in a waiting room until the next train came? Would that next train have sufficient sleeper accommodations for the airline passengers?

The next problem was that the first Ford Tri-Motor only carried 11 passengers. That soon went up to 15. It was totally uneconomic to run a sleeper train for only 15 passengers. Hence, the connecting trains for night service virtually had to be regularly scheduled trains. This seriously limited options and scheduling for the planes.

Finally, the plane-train connections had to be made at locations where railroads and airports were adjacent. This again created some limitations. Alook at the Transcontinental Air Transport operation shows plane-train connections at Port Columbus, Ohio; Waynoka, Oklahoma and Clovis, New Mexico. It apparently took a little head scratching to figure out how to make an operation like this work.

As the astute reader has probably guessed, there was one solution to all of these problems. That was to use a bus with sleeping facilities for providing the night service. With a dedicated sleeper bus, it could afford to wait for a late plane while a train could not. The bus could be set up for sleeping 15 passengers and possibly a few more and hence would be exclusively used for the passengers from one plane. The third advantage of the bus was that it was not limited by railway tracks. It could meet planes at virtually any airport. This also gave the bus the ability to meet planes at different locations in the event that bad weather or

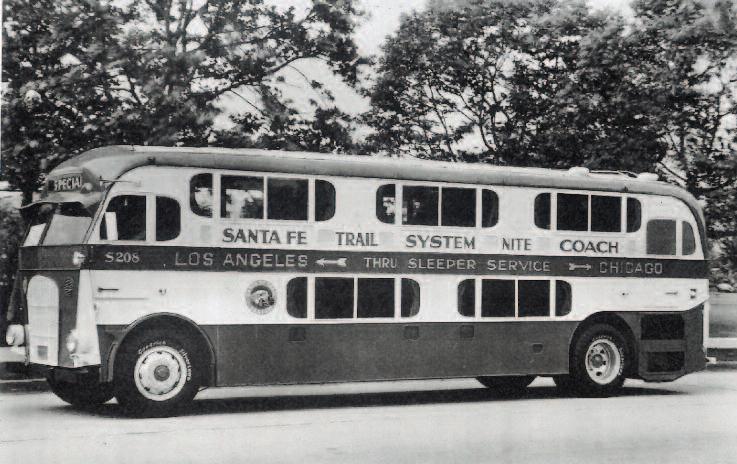

The Duplex was a seated version of the Nite Coach that could carry 53 passengers. Greyhound operated this model from Chicago to Detroit and St. Louis and from New York to Boston and Washington. Pickwick Airways operated from Los Angeles south to Mexico and Guatemala with tri-motor planes. The stock market crash and following recession forced it to go out of business in the spring of 1930.

some other reason forced planes to make a landing. The railroads could not do this.

The Nite Coach was developed to meet this need. Pickwick already had the experience and expertise in building buses at its Los Angeles shop. The company apparently saw the Nite Coach as an expanding market to partner with aviation. In fact, there were suggestions that Pickwick was thinking of leasing their sleeper buses to the airlines just like Pullman leased sleeping cars to the railroads.

Pickwick started moving toward aviation in 1928. Pickwick Airways was formed that year and 10 tri-motored airplanes were ordered. The route between Los Angeles and San Diego started operating in March of 1929. By September of 1929 the route had been expanded south to Mexico City and Guatemala.

Pickwick also got started building higher class buses. The first prototype was built on Pickwick’s preferred Pierce-Arrow chassis. This unique design had an upper level a small galley, a rear observation lounge and a raised driver’s area. It was named Cherokee since Pickwick often used names instead of numbers for their buses. This bus was put in service on the San Diego-Los Angeles-San Francisco route, but it was never duplicated.

Dwight Austin, Pickwick’s vice president, was in charge of building the Nite Coaches. It immediately became obvious that the large coach planned could not be built on a PierceArrow chassis. Austin developed the basics for what came to be called integral construction. This involved a “backbone” of two rails running the length of the coach and protecting the rear. In addition, Austin developed the transverse engine and V-drive to make the design more workable.

The first of the Nite Coaches was named Alsacia. It had 13 compartments, each accommodating two people, somewhat like a Pullman car. Seats were provided for day travel and berths for sleeping at night. There was only one center aisle although the berths were located on two levels with passengers either stepping up or down into the compartments. Other features included lavatory facilities and a small galley for food service. Each coach was apparently crewed by a driver, a steward and a chef.

Pickwick management made the decision to get out of bus operations entirely and concentrate on bus building and aviation. Adeal with Greyhound in 1929 led to the formation of Pacific Greyhound Lines that merged Pickwick’s routes with those of Greyhound. Included was the Pickwick fleet of 359 units. Pickwick received a payment of $1.5 million. This helped Pickwick in making the investment to build a bus factory in the Los Angeles suburb of El Segundo. The Aftermath

While there were several factors involved, the one that had the most influence on the future was the stock market crash on Black Tuesday, October 29, 1929, and the following Great Recession. This had a major impact on business and industry.

Commercial aviation initially suffered from a loss of passengers. However, technology took some major steps forward at this time. The new Douglas DC-2 was introduced in 1934 and was named the first airplane that could make money by many in the business. American Airlines talked Douglas into expanding the DC-2 slightly into a sleeper plane, which gave birth to the ubiquitous DC-3. By 1936, the new Variable Omni Range system was supplanting the

This photo provides some idea of the concept of traveling by plane during the day and transferring to a Pickwick Nite Coach at night. The Nite Coach provided many of the same amenities as a train including a comfortable berth, a lavatory, food service and even running water. The bus, however, could be more versatile than the train because it could afford to wait for a late plane or connect with planes at virtually any airport.

old airways. New airways were created by flying at various “radials” (compass headings)toandfromeachVOR.Insteadofneeding buses for night travel, the airlines had sleeper planes traveling at night.

Several people in the industry suggest that Pickwick made the wrong decision to give up on buses and concentrate on aviation.HadPickwickmovedintheotherdirection and purchased Greyhound, we might have seen the Pickwick name on the side of the Scenicruiser.

Pickwick Airways folded in early 1930. The Nite Coach never partnered with aviationforanylengthoftimeandonlyalimited number were built. A few operated on the West Coast and some in the Midwest, but size restrictions were a problem in some places. Some of them operated as late as 1942. The same design was offered as a seated coach, known as the Duplex. It provided seats for 50-54 passengers on two levels. While it was more successful than the Nite Coach, it never reached any volume production.

After the demise of the Nite Coach, Austin went on to develop a small bus known as the Utility coach to keep production alive at the new El Segundo factory. It had an angle drive, a transverse rear mounted engine and a capacity of 21 passengers.Itsintegral,chassislessconstruction wasconsideredremarkableatthattime.Like the Nite Coach, the Utility coach was pioneering but not very profitable.

Following the end of Pickwick, Austin joined Yellow Coach in 1934. He helped General Motors develop the Model 719 Supercoach that had a rear engine, underfloor luggage compartments and the start of GM’s integral construction. In the following years, Austin’s rear transverse engine, V-drive and integral construction became typical on the more popular GM coach models. q

Among the last of the Nite Coaches built was a 1932 order that apparently originally operated for Columbia Pacific. The company was purchased by the original Burlington Trailways, but the coaches went to Santa Fe Trails. Note the improved design including a more modern front. Some of the Nite Coaches operated as late as 1942.