20 minute read

BEFORE HE JOINED CALARTS FACULTY, JOHN BALDESSARI

Every experience is different. We didn’t know that Ocean’s Eleven was gonna be anything when we did it. We were just like, “Oh, this is a cool movie.” And I’ve worked with Steven [Soderbergh] before, and we stayed in touch.

I would bring my other friends. If they had one, they’d bring us. The casting directors were really tripped out because obviously it’s like if you get a job, then your friend can’t get a job. And if your friend’s gonna get that job, then you can’t get the job. We’re not really in competition with each other for individual roles. And anyway, at least one of us needs to get it because we’re all borrowing money from each other so we can pay rent, right?

Somebody in this crew needs to get it, somebody needs the job. So I think what actually happened, interestingly enough, was that we kind of became the darlings of these casting directors at the time, because we’d all show up as a pack and hang out with them and be goofing around and they would watch us perform. And it was just a whole thing. So that was kind of unique.

I don’t think we ever know. And the same thing goes for Marvel. Nobody knew that it was gonna do what it did. It’s trickier, obviously, when you’re in something like that as opposed to something like Things Behind the Sun, where you’re very small. There’s no bells and whistles. You’re there for the love of the game. You’re not making any money, and you’re not there for that reason. You’re trying to tell a real specific and important story. Those are the ones that I really love being a part of. It’s sad that those are so hard to find, and no one’s really making them. You have to grind so hard to get those made. It’s fun doing the Marvel stuff, and you get all of the bells and whistles and all the toys and all the cool shit to work with. In those movies, you’re working with a lot of good actors because a lot of strong actors are doing those movies now. At some point, everybody will be in a Marvel project, either on streaming or in the movies. But yes, they’re very different. At the core of it, though, you’re still trying to do the same thing. You’re still trying to find the truth of the character, the truth in the moment where you fit in the story.

GATHERED ALL OF HIS PAINTINGS IN HIS POSSESSION AND BURNED THEM. HE THEN FOLDED SOME OF THE ASHES INTO COOKIE DOUGH AND DISPLAYED THE BAKED COOKIES AS PART OF INFORMATION, A GROUNDBREAKING 1970 SURVEY OF CONCEPTUAL ART AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART IN NEW YORK.

You mentioned some of the other films that aren’t as appreciated and valued. As a storyteller, how does advocacy play a role in your work?

Let’s talk about your music and interdisciplinary practices in general. I loved you in Miles Ahead and Talk To Me. How have music and other practices besides acting played a role in your career? They work with one another. Language is music and a lot of what happens in script analysis. I think when you’re trying to understand not only a character but a story, there’s a lot that has to do with rhythm and there’s a lot that has to do with space, which is a big part of music as well as acting, obviously. Listening, being permeable, porous, and open, and allowing things to affect you. To be in this feedback loop of you affecting it, it affecting you. Finding that sweet spot where those things are just naturally happening. It’s magic when it happens.

You’ve been in a lot of films or stories that end up having such a wide audience—either cult classics or giant projects. What is it like as an actor being in something like Boogie Nights or something like Ocean’s Eleven that has a cult-classic feel to it, as opposed to something like Marvel films, which have become part of a giant Disney conglomerate?

As a producer, I’m always trying to support those voices and trying to center those who have not been centered and bring people to the table that, as you say, are often overlooked. As an actor, I’m often trying to find those storylines within that. It’s not just in front of the camera. I have a diversity mandate and have had one long before that became a thing to do. Always trying to make sure that the crews look like the world and that we always have people that are allies. That’s a big part of it. In this post-George Floyd moment, a lot of companies started having these wake-up calls and looking at their practices and realizing, “Wow, we’re not participating in the world in a way that’s conducive to really supporting everyone.” Some have done a 180. What I also feel now is there’s been kind of a blacklash, proceeding back to the normal that it was prior to this. We’re still struggling to find space and create opportunities for people. That’s always been, and not just in my professional life but in my personal life, something that’s important to support.

Jo Siri: So it was through your high school teacher that you came to CalArts. Tell us more about that.

Don Chea D le: I had an audition at CalArts, and it was a really bad audition. I think I did a Molière. I kind of forgot the monologue halfway through and then thought, “OK, I’ll just improv.”

I’m used to jazz [laughs]. The dean stopped me and she’s like, “I don’t know what that was. It’s a wrap, basically. We’re good.” And I said, “No, no, no, I have another piece. Let me do my other piece!” It was from The Shadow Box And she was like, “OK, that was really good—because you were outta here after that Molière thing.” But somehow I got accepted, and I went to CalArts and spent four years there studying. Do you have a favorite moment that you hold onto from your four years at CalArts? A special play, a workshop, a teacher?

I had an amazing time at CalArts. I wouldn’t trade it for the world. The friends I made there are still lifelong friends. Jesse Borrego ... his daughter is my goddaughter. She and my kids actually live together and are extremely close. Myself, Bruce Beatty, Geoff Thorne, Rhys Greene took the initiative and performed plays on our own in the Black Box Theater, no help from anybody. We just did ‘em. We did Fugard plays, ‘Master Harold’ ... and the Boys, The Island, too. Everybody came. It was in one of those spaces above the Main Gallery … E400? Are they still up there? Yeah, they are. During my freshman year, there were amazing studentled projects in E400. Students got together and made beautiful work. Now usually they’re in the Coffee House, and it’s still the same thing. Really? That’s so wild. Yeah, those spaces were the space. Those were our main theater spaces. Those, and when you got to do something, obviously in The Mod, you’re like, “Whoa.” But most of our things were in those black-box spaces. CalArts hasn’t really changed much. I mean our Halloween party, my first year there, Los Lobos performed. And the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

No way. Are you serious?

I would bring my other friends. If they had one, they’d bring us. The casting directors were really tripped out because obviously it’s like if you get a job, then your friend can’t get a job. And if your friend’s gonna get that job, then you can’t get the job. We’re not really in competition with each other for individual roles. And anyway, at least one of us needs to get it because we’re all borrowing money from each other so we can pay rent, right?

Somebody in this crew needs to get it, somebody needs the job. So I think what actually happened, interestingly enough, was that we kind of became the darlings of these casting directors at the time, because we’d all show up as a pack and hang out with them and be goofing around and they would watch us perform. And it was just a whole thing. So that was kind of unique.

Let’s talk about your music and interdisciplinary practices in general. I loved you in Miles Ahead and Talk To Me. How have music and other practices besides acting played a role in your career? They work with one another. Language is music and a lot of what happens in script analysis. I think when you’re trying to understand not only a character but a story, there’s a lot that has to do with rhythm and there’s a lot that has to do with space, which is a big part of music as well as acting, obviously. Listening, being permeable, porous, and open, and allowing things to affect you. To be in this feedback loop of you affecting it, it affecting you. Finding that sweet spot where those things are just naturally happening. It’s magic when it happens.

You’ve been in a lot of films or stories that end up having such a wide audience—either cult classics or giant projects. What is it like as an actor being in something like Boogie Nights or something like Ocean’s Eleven that has a cult-classic feel to it, as opposed to something like Marvel films, which have become part of a giant Disney conglomerate?

Every experience is different. We didn’t know that Ocean’s Eleven was gonna be anything when we did it. We were just like, “Oh, this is a cool movie.” And I’ve worked with Steven [Soderbergh] before, and we stayed in touch.

I don’t think we ever know. And the same thing goes for Marvel. Nobody knew that it was gonna do what it did. It’s trickier, obviously, when you’re in something like that as opposed to something like Things Behind the Sun, where you’re very small. There’s no bells and whistles. You’re there for the love of the game. You’re not making any money, and you’re not there for that reason. You’re trying to tell a real specific and important story. Those are the ones that I really love being a part of. It’s sad that those are so hard to find, and no one’s really making them. You have to grind so hard to get those made. It’s fun doing the Marvel stuff, and you get all of the bells and whistles and all the toys and all the cool shit to work with. In those movies, you’re working with a lot of good actors because a lot of strong actors are doing those movies now. At some point, everybody will be in a Marvel project, either on streaming or in the movies. But yes, they’re very different. At the core of it, though, you’re still trying to do the same thing. You’re still trying to find the truth of the character, the truth in the moment where you fit in the story.

You mentioned some of the other films that aren’t as appreciated and valued. As a storyteller, how does advocacy play a role in your work?

As a producer, I’m always trying to support those voices and trying to center those who have not been centered and bring people to the table that, as you say, are often overlooked. As an actor, I’m often trying to find those storylines within that. It’s not just in front of the camera. I have a diversity mandate and have had one long before that became a thing to do. Always trying to make sure that the crews look like the world and that we always have people that are allies. That’s a big part of it. In this post-George Floyd moment, a lot of companies started having these wake-up calls and looking at their practices and realizing, “Wow, we’re not participating in the world in a way that’s conducive to really supporting everyone.” Some have done a 180. What I also feel now is there’s been kind of a blacklash, proceeding back to the normal that it was prior to this. We’re still struggling to find space and create opportunities for people. That’s always been, and not just in my professional life but in my personal life, something that’s important to support.

Jo Siri: What movies and music inspired you growing up?

Don Chea D le: I’ve always been into jazz from a very young age and was listening to the albums that my parents had—Miles Davis; Earth, Wind & Fire; The Spinners; as well as classical albums. My parents were pretty eclectic, and it just continued from there. I loved the artistry. I love listening to people who can really play their instruments and really do their thing. I still have a pretty eclectic palate for the music that I love. So we were listening to everything.

In terms of movies, I was very fortunate to grow up during a golden age: ‘70s movies—The Godfather, Dog Day Afternoon—you can go down the line. Great filmmakers and great stories. That’s what I grew up on. I really miss that kind of storytelling and that kind of attention to detail and taking your time. The Godfather was on the other day, and you look at the sequence where he finds the horse’s head in his bed, how long it takes to actually get to the horse’s head. They would cut that all out today. We don’t have the attention span. And social media and every aspect of our popular culture has, I believe, just undercut our ability to sit in something, not want to rush to the end. It’s sad because I think we’ve missed out on a lot in the desire to make sure that somebody doesn’t change the channel or make sure that somebody doesn’t get bored. Is there an actor that inspired you? My dad said you reminded him of Paul Robeson when he first saw you on screen. He was really taken aback by your performance. Wow, that’s amazing. I mean, a lot of them. The great ones, right? Denzel [Washington], Laurence Fishburne, a great performer. Meryl Streep, Robert De Niro. I think Maggie Gyllenhaal is really good. Gary Oldman is amazing. Tom Hardy.

I do think they’re few and far between, right? There’s not a ton of amazing anythings—doctors, painters, lawyers. It’s not easy to be excellent and stand out in your field. I think that when you do it, it’s because of not just your practice and your study and your focus, but there’s something also that’s nebulous. You can’t necessarily determine what it is that makes someone compelling to watch.

What’s your hope for the future of the industry?

You’ve mentioned in past interviews that this is a very different industry than when you started.

I think it cuts both ways right now. It’s a very good time to try to be a part of this because there are so many platforms and there are so many places that are desperate for content and that need performers and actors and creatives, writers. All of these different seats need to be filled for all these different projects. There’s always going to be the crucible that you have to figure out how to get through, but at least there’s more opportunities. Now let me qualify that by saying, as I said earlier, at the same time I see that potentially the window is closing, so it’s high time to do it now. We’re seeing something that never would happen when I came out. Now when people wanna cast you in a movie they are checking how many followers you have on social media, and that could be a determining factor on whether you get a gig or not, which is bananas to me.

To wrap up, I want to thank you for your continued work in theater—I know you still are continuing with things like Strange Loop. Thank you for your work in film, obviously for many reasons. Thank you for your involvement in the community at CalArts specifically, and the work you do on the Board of Trustees. I also want to thank you for supporting marginalized voices. Hosting Saturday Night Live and choosing to wear the “Protect Trans Kids” shirt was very powerful. It was a proud day for CalArts. It’s such a simple and important thing to say. It’s crazy that it’s radical, but it was. Thank you for that work, and thank you for your time today as well.

Thank you very much. I appreciate that. ⁂

Don Cheadle’s Prolific Career (So Far)

BY Greg Houle

Don Cheadle hosted Saturday Night Live in 2019 and wore a statement.

’86 ’90 ’00 ’04 ’07 ’10 ’15 ’19 ’21 ’22

’ Upon graduating from CalArts, Don Cheadle (TheaTer BFa 86) scored supporting roles in such decade-defining television series as Fame, Hill Street Blues, L.A. Law, Night Court, and The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, as well as the Vietnam War-era film Hamburger Hill and the action movie Colors. ’ By the early 1990s, Cheadle had booked his first starring role, in the The Golden Girls spinoff The Golden Palace, which aired for two seasons on CBS. ’ His first major film role came in 1995, alongside Denzel Washington in Devil in a Blue Dress. That performance caught the attention of critics, earning him Best Supporting Actor awards from the Los Angeles Film Critics Association and the National Society of Film Critics, as well as nominations from the Screen Actors Guild and the NAACP Image Awards. ’ By the late 1990s and early 2000s, Cheadle had become a prolific actor, appearing in a range of popular and critically acclaimed films, including Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights and the Steven Soderbergh projects Traffic and Ocean’s Eleven. ’ In 2004, Cheadle’s much-lauded performance as activist Paul Rusesabagina in Hotel Rwanda garnered Best Actor nominations from the Academy Awards, the Golden Globes, and the Screen Actors Guild. That same year, he also appeared in, and co-produced, the eventual Academy Award-winning Best Picture, Crash, where he also earned a Best Supporting Actor nomination from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts. He received a 2004 Grammy nomination for Best Spoken Word Album for his narration of the Walter Mosley novel Fear Itself. ’ An outspoken activist and humanitarian, Cheadle co-founded the nongovernmental relief organization Not on Our Watch with George Clooney, Matt Damon, Brad Pitt, David Pressman, and Jerry Weintraub, with the goal of bringing attention and aid to those suffering atrocities in Darfur and around the world. He received a BET Humanitarian Award and the Peace Summit Award by the Nobel Peace Prize Laureates for his work in support of the people of Darfur and Rwanda in 2007. Cheadle also serves as a Goodwill Ambassador for the United Nations Environment Programme, among other charitable activities. ’ In 2010, Cheadle began starring in the blockbuster Marvel franchises: Iron Man, Avengers, and Captain America. To date, Cheadle, as James Rhodes/War Machine, has appeared in seven Marvel films.

’ In 2015, the actor made his directorial debut—as well as co-writing, co-producing, and starring as Miles Davis— in the unconventional biopic Miles Ahead. ’ On the small screen, Cheadle earned a Golden Globe for Best Actor in a Television Series and an NAACP Image Award for his performance as Marty Kaan in House of Lies, which he executive produced for its five seasons on Showtime. From 2019 to 2021, Cheadle starred in and executive produced the series Black Monday, also on Showtime. ’ In addition to his work as an actor, director, and producer for films and television, Cheadle produced the 2022 Tonywinning Broadway musical A Strange Loop

FOOD FOR THOUGHT:

Alarge kiddie-sized pool filled to the brim with Flamin’ Hot Cheetos. Cardboard cut-outs celebrating a quinceañera. At first, they don’t seem to have much in common. But both connect to themes that run through much of Jazmín Urrea’s visually striking work: an exploration of her Mexican and Honduran cultures and food. “Food makes it

Urrea (arT MFa 17) grew up in South Los Angeles, where she lives to this day. It was here, during a senior-year journalism class, that she developed an interest in photography, capturing images to accompany articles. It was also where, in middle school, she and her friends stopped at convenience stores before and after school to fill up on Gatorade, spicy candies, and her favorite snack: Flamin’ Hot Cheetos. We’re not talking about those little vending machine baggies. We’re talking jumbosize bags, which she’d consume all day long. Eventually she reached a point where she was subsisting mainly on Cheetos, swapping them for breakfast and snacking between and after lunch and dinner. Dessert? Hot Cheetos.

One night, Urrea woke up shivering and her mother took her to the ER. At first, doctors weren’t sure what was causing Urrea’s symptoms. But ultimately they determined her appendix was about to burst. She went into emergency surgery where doctors removed it. “The doctors told my mom that it was my diet,” she said. “Essentially, the dyes and the Cheetos irritated my appendix.” The worst part? “As I was recovering, I was literally asking them, ‘So, I can still eat hot Cheetos, right?’” Yes, they told her, in moderation.

But as a kid, Urrea really had no guidance as to what a balanced or healthy diet entailed. She also had no idea that she lived in a food desert: an urban area where access to fresh, healthy, and affordable food is limited, which can lead to a variety of health conditions, including diabetes and hypertension.

A 2018 study from the Center for Urban Resilience and Loyola Marymount University found that while South LA grocery stores had fresh, local produce, such stores were few and far between. About 94% of all food stores were actually convenience stores. There were also 12.5 times more fast food restaurants than grocery stores. For Urrea, if it hadn’t been Cheetos, it likely would have been another highly processed snack.

It wasn’t until she began carpooling and driving between her South LA home and CalArts that, she says, “I started seeing how much more accessible grocery stores and healthier foods were in Santa Clarita and Valencia.” Her work since has often explored the concept of food deserts and her personal experience living within them, often imagining them as “alien landscapes.”

In Imperishable, part of LA’s 2019 Public Art Triennial Current: LA Food, which featured art installations across 15 public parks, Urrea filled six 8-foot-tall Plexiglas towers with Flamin’ Hot Cheetos. They stood in a circle in South LA’s Martin Luther King Jr. Park. She describes the piece as one of the most difficult she’s made, requiring her to work with a structural engineer and a construction crew to ensure the pillars and their concrete bases wouldn’t collapse. Though individual Cheetos seem airy, each tower weighed between 800 and 1,000 pounds. “I wanted you to feel like you were encased by Cheetos—a sense of drowning in them,” Urrea says. “I just wanted you to feel what it’s like to live in that world—surrounded by so much of something that is considered super bad for you. It’s standing as a representation of what certain communities are facing.”

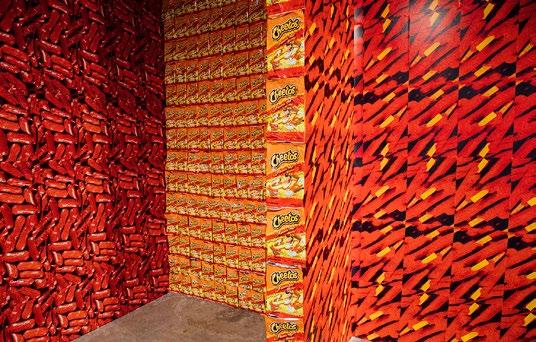

Other works have incorporated Cheetos as well. In RED 40, Urrea’s 2017 CalArts thesis project, she filled a pool with about 300 pounds of the puffed cornmeal. The title comes from the particular artificial dye that gives Flamin’ Hot Cheetos their searing red color.

In I Saw Red at Gallery Sade in Lincoln Heights, Cheetos lined the floor of a Technicolor labyrinth, its walls plastered with photographs of candies. Cheetos crunched underfoot as guests navigated the maze, filling the air with what Urrea describes as the snack’s “pungent, disturbing odor.” (Weirdly, some people asked if they could eat them. Urrea had to warn them that they weren’t exactly in a sanitary setting.)

After dabbling in photography in high school, Urrea enrolled at Cal State Long Beach, where she earned a BA in Fine Art Photography (2014). “I always like to say that photography gave me an outlet to turn the camera on myself, to immediately document all of my surroundings and just explore my environment,” she says. “It was a gateway to explore all these different narratives.”

During her undergrad years, she began taking self-portraits in which she cast herself as a variety of stereotypes often directed at Latinos/Latinx people like her and her family. “People would assume I was gonna be a chola or that I was gonna end up pregnant and drop out of school,” she says. She turned those self-portraits into life-size cardboard cutouts, then photographed them in various real-world scenes: a leering construction worker standing on a loading dock, a pregnant woman in a tube top flashing the peace sign outside a discount fashion store, a woman in a low-cut top and blonde wig smiling in the front window of a trendy boutique.

After graduating, Urrea took a gap year before applying to a handful of art schools. When she received her acceptance letter from CalArts, she was “ecstatic.” To honor the achievement, she wanted to create another cutout piece that, rather than addressing stereotypes, paid tribute to her background, “like a coming-of-age celebration.”

Well before they reached Urrea’s age, many Latinas would have had a quinceañera, a coming-of-age celebration that marks a girl’s transition to womanhood on her 15th birthday. For the occasion, the girl usually dons a beautiful dress and is surrounded by family and friends. The tradition is marked with lots of food, photos, and dancing.

Urrea’s mother, however, found quinceañeras unnecessary, so Urrea never had one—but her cutouts did.

For Quince Años, Urrea posed her cutouts in CalArts’ Main Gallery and lit them like performers on a stage, where they stood greeting entrants with their smiles. Urrea put herself in every cut-out: the birthday girl in a beaded white dress and tiara with her court of honor. The artist wore burgundy dresses and heels as the girls and black tuxes as the boys. For the show’s opening, she threw, well, a quinceañera replete with music, tamales, and horchata. She enjoyed explaining her piece during critiques to those from other cultures who were unfamiliar with the custom, as well as hearing from those who thanked her for showcasing their shared backgrounds. “And because I had been working with negative associations of being a Latina, it was uplifting having that conversation of positivity,” she said.

Throughout her time at CalArts, Urrea appreciated its supportive faculty and the freedom to explore. “I wouldn’t say necessarily everyone understood what I was doing, but they were definitely supportive, like, ‘No, go for it. This is what you’re here for,’” she says with a laugh.

She particularly enjoyed the mentorship of artist Harry Gamboa Jr., co-director of the Program in Photography and Media, whom she’d admired and hoped to work with when applying to CalArts. She recalls field trips exploring Downtown Los Angeles by Metro and on foot as part of his LA Urbanscape course, and how he frequently told stories about his life experiences, which would ultimately help her figure out what she was doing in her own work. “At first, you’re like, ‘Wait, why am I listening to this story?’ But then somehow, it comes full circle,” she says. “I’m an LA girl, Harry is an LA person. I think our experiences really helped create a strong relationship, and I was really happy that he was my mentor.”

The goal of LA Urbanscape, Gamboa says, is to introduce students to “the broad socioeconomic spectrum of LA.” He remembers that Urrea accompanied him on his longest exploration, a 12-hour journey from East LA to Beverly HIlls. “Along the way, we were talking about what it is to attribute an experience to a particular space,” he recalls. “She was reflecting on a lot of that, and I think it was during that that she really started talking about her own experiences of having an adverse effect from eating too many hot Cheetos.”

Gamboa was in Europe as Urrea assembled RED 40, but he was able to see the piece shortly before the show opened at CalArts. “It looked like that work could have been anywhere in Paris or Berlin or Stockholm,” he said. “I told her this work looks like it’s ready for a museum. Not everyone gets to the top of the learning curve so quickly.” He recommended she reach out to local journalists. She did, and several outlets covered the project. A month later, Gamboa returned to Europe, where “all the young students were excited I knew Jazmín Urrea.”

Urrea often misses the structure of academia and the collaborative environment of creative individuals who are constantly seeing and discussing one another’s work. But she hasn’t left academia entirely behind. Urrea taught classes with Artworx LA, a nonprofit that offers arts programming to LA students, before the pandemic shut down in-person education. She’s now working at ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena in the graduate art department. She runs the print lab and does exhibition photography, and she has the option to teach. “I just haven’t figured out what I’d like to teach,” she says.

The artist eventually plans to revisit her cut-outs and would love to do more public artwork akin to Imperishable “It gave me the opportunity to bring my work to a different audience,” she says. “I loved being able to have different conversations and provide a platform for people to be able to share their stories.”

In the more immediate future, Urrea is working on a new sculpture series incorporating candy—and diving back into the Cheetos pool. Her newest iteration of RED 40 is part of this spring’s Mexicali Biennial, on view through May at The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture of the Riverside Art Museum. ⁂