35 minute read

NEWS OF THE WORLD

News of the World Western Vérité

an interview with Martin Schaer, SOC by David Daut

(L-R) Johanna Leonberger (Helena Zengel) and Captain Jefferson Kyle Kidd (Tom Hanks) in NEWS OF THE WORLD, co-written and directed by Paul Greengrass. Photo by Bruce W. Talamon / Universal Pictures

News of the World, based on the 2016 novel, tells the story of Jefferson Kyle Kidd (Tom Hanks), a former captain in the Confederate Army, who travels across Texas reading the news to anyone with ten cents to hear it. As he wrestles with his place in the aftermath of a country torn apart by war, he finds a young girl (Helena Zengel), orphaned and abandoned, and begins a journey to reunite her with her family. The film is directed by Paul Greengrass from a script by Greengrass and Luke Davies. News of the World has been nominated for several industry awards such as four nominations for 2021 Academy Award Oscars, including a nomination to Dariusz Wolski for Best Achievement in Cinematography. Wolski also received a 2021 BAFTA nomination for Best Cinematography . WATCH TRAILER NOW

Camera Operator: I know you’ve worked with cinematographer Dariusz Wolski many times in the past, but if I’m not mistaken, this is the first time either of you have collaborated with Paul Greengrass. How were you approached to work on this movie? Martin Schaer: The first movie on the West Coast both Dariusz and I met and worked on was a movie titled The Oasis. It was a movie in the early 80s about a plane crash in the Mexican desert, people struggling to survive, resulting in cannibalistic behavior; this low-budget movie was before Alive where a soccer team crashes in the Andes and has to survive, eventually feeding on their dead. Guess there was an “appetite” for these kinda stories! This is how Dariusz and I met the then-production associate, Gregory Goodman, who later produced News of the World and a handful of other Paul Greengrass movies. Through Gregory, I got calls to work on Paul Greengrass projects before, but this was the first one that really fit, especially after Dariusz asked me to do News of the World with him. So we reunited with Greg Goodman as producer and it became like old times. Gregory knew of Dariusz and Paul Greengrass liked his work. Paul always chooses people to do his movies who have an unusual creative history and embrace filmmaking outside the mainstream. Kinda cool when things come full circle. CO: As a director, Paul Greengrass is sort of famous for his use of handheld cameras and the so-called “shaky cam” style, while westerns, at least traditionally, tend to skew in the other direction. How did you go about finding the visual language for this film? Schaer: Let’s face it, an operator is—in the end—adapting to the visual style chosen by the director and the cinematographer. So, I think that was both Dariusz’s and my own first question: what was that style going to be? Are we going to do what Paul Greengrass always did, or are we going to find a somewhat different style? Dariusz already early on approached Paul with the suggestion to sort of tone camera movement down. In the beginning, his idea was to just go controlled as the characters are traveling through the landscape with tracking shots and all sorts of stabilizing systems to keep things calm, consequently when the action comes in it would evolve into handheld and a visual style that’s a little bit more action oriented. Paul is very much into the movement and free style, flowing handheld, so we settled for a mix between controlled handheld and Steadicam, still keeping things alive and breathing. As we found out during filming, Paul is a huge fan of the Maysles brothers—New York documentarians—and it just so happened that I have worked on many films with Albert Maysles. Back in my early operating years (introduced by Ed Lachman!) I was hired to come in as a second camera because often Albert would position himself in a corner and, in the cinéma vérité style, had his 16mm Aaton on his shoulder and just filmed whatever was going on, like being a fly on the wall, so to speak. Albert, as the conceptual brain and cameraman, was never aggressive in telling people where to stand, what to do—that wouldn’t be cinéma vérité. That was something that always interested and fascinated Paul in terms of filmmaking; not so much controlling it, but instead letting things go and see how takes and scenes fall into place. That includes the actors, but nevertheless he does still talk the actors through the essence of a scene and what he intends to do so they understand the basic concept, that moment he wants to get on film. After that the cameras come in and we get a talk, and from then on he lets it kind of happen. So if he feels and sees it, he’s a very happy man, and if he doesn’t see it, he tries again. But it’s not, “the camera has to do this,” it’s more making sure that we understand the concept. In that sense it’s feature making in an almost cinéma vérité style. Consequently that intuitive handheld style was developed. Albert Maysles also shot everything handheld, all the time. We had tripods along, but very seldom did we ever use a tripod. Albert, of course, was a little more deliberately quiet and calm about it—he didn’t move around, often did not cut—where Paul often take it to another level and says, “give me some life, it’s okay when it shakes.”

Director and co-writer, Paul Greengrass with B camera operator, James Goldman on the set of NEWS OF THE WORLD. Photo by Bruce W. Talamon / Universal Pictures

To answer your question, Paul started prep in London and we took pictures of locations in New Mexico so Paul could see what he was dealing with. A week before shooting started, he came to Santa Fe, New Mexico, we had him on the set, we decided that we would mostly be doing handheld, but we would use Steadicam whenever we had scenes that required walk and talk which need to be a little calmer. James Goldman did a stellar job walking with the wagon, and with both of us being on the wagon and shooting the actors when it’s very bumpy, the Steadicam came in handy. We pretty much decided to nix all the gadgets like insert cars, camera cars, remote crane arm. We had them on hold just in case we wanted them, but we abandoned all of it in that week before shooting. Steadicam and handheld became the simple answer for the look of the movie.

James Goldman, was the B camera and Steadicam operator; always positive energy, very talented craftsman, was with us from early on in the Pirates of the Caribbean movies as a kind of lab liaison/third assistant. He started very low in the camera department 20 years ago and moved up, got himself a Steadicam, and started energetically working on it. He became top-notch. For me, it was comforting and rewarding to see James moving into a savvy, creative partner-operator position. I find it always refreshing to have younger blood and energy in the camera department. Together we worked on balancing/smoothing the obvious differences between handheld and Steadicam.

CO: And I think that balance works really well! In particular, I think about the shootout sequence in the middle of the movie where there are those moments of frenetic action, but then you also have these moments of stillness. Especially when they’re hiding under the rocks, trying to avoid being found by the bandit. Schaer: Due to the dangers in this steep, cliffy location, we shot the two principles— Tom and Helena—first in the rocks in their key positions, laid out by Paul and Dariusz, based on what they had in mind. From the beginning, they both had it in mind for me to shoot second unit. It was scheduled so that I would be there with first unit, and then go back with a 50-head second unit to plug in and cover the bad guys. We had them pretty much the whole time; they were all pretty good trained riders, so we could do some pretty harrowing stuff to spice up the action. So, I do think in a way Paul really did change his style. I mean, he agreed to go with certain things which maybe before he wouldn’t have, but he also knew that Dariusz, James and I would be listening to what he had to say and what he wanted to do. You know, this was my first time I met Paul, so when

he heard that I had worked with the Maysles brothers on many films, he got a huge smile on his face and hugged me. It wasn’t that we imposed another style on him or took over, it was still his vision, he had a great appreciation for all of us. The only addition is that we did carry a dolly and occasionally used it when we tracked behind the public listening to his speeches. We actually shot about five times more speeches than were in the movie; a lot of editing had to be done so that only the best parts were used. One further note about the equipment: we still had to come up with a camera vehicle of some sort because there was so much riding through the desert on the wagon, we had to follow them in wide shots which could sometimes be impossible using just a Steadicam. So we ended up renting a Ram 1500 pickup truck and our key grip, Mike Popovich, built a camera car out of it with a speed rail in the back, side, and front. The fancy exception was on second unit where I had to use a dune buggy with a stabilized head for a couple of shots that had to be stabilized for face replacement. So, in that way it was a rather organic way of filming; less is more, sitting with the actors, strapped in on the carriage, and doing handheld when it was smooth enough, and only when we got into the more remote locations with rocks and roots that we’d use the camera car (aka speed rail pickup) or James would walk backwards with Steadicam next to carriage going with the trot of the horse. CO: Westerns are something of a rare breed these days, but this isn’t the first western you’ve done. I know you also worked with Gore Verbinski on both Rango and The Lone Ranger—two movies I personally love very much. How did your work on News of the World compare to those earlier films you did? Schaer: The biggest difference was exactly what we were just talking about. On The Lone Ranger we had virtually all the toys and tools that were available. That ended up being something like a $200 million movie, and we had trains built which were specifically adapted for remote cranes—we were able to put the Technocrane on the train itself. We had five miles of our own selfbuilt track in the desert with switch tracks and parallel tracks and stations. We carried a short technocrane as well as a long, 50-foot Technocrane for the whole show. We had Steadicam, of course, plus countless cameras, both film and digital. As I said, everything was available, and whatever we needed, that’s what we’d get. Sky’s the limit. We mixed all the styles drastically. Let’s note, Gore is not a documentarian. He’s a very well-prepared craftsman, a filmmaker who controls every aspect of his set. He’s a savvy multitasker, and he thinks about things beforehand. Same thing with Rango. It was an animated movie, but what Gore initially wanted to do was record the entire film on videotape with

Photo by Bruce W. Talamon / Universal Pictures

On the set with Tom Hanks and B camera operator, James Goldman. Photo by Bruce W. Talamon / Universal Pictures

TECH ON SET: Alex Mini LF; Alexa Studio LF; Angenieux EZ Zooms; PANAVISION P70 Vintage Primes; Steadicam; Easyrigs

TRIVIA: News of the World marks Tom Hanks' second feature with British director Paul Greengrass, the first being Captain Phillips (2013).

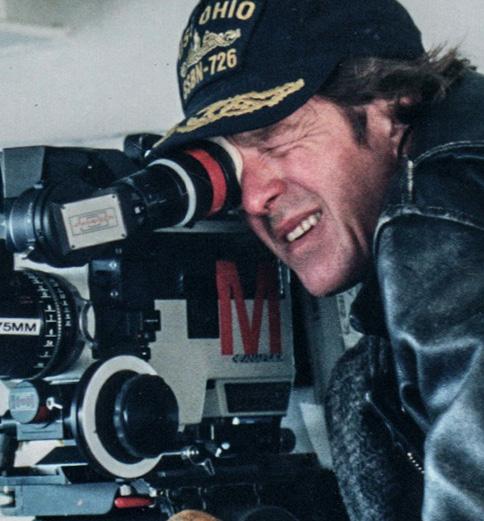

Director and co-writer, Paul Greengrass and Martin Schaer, SOC on the set of NEWS OF THE WORLD. Photo by Bruce W. Talamon / Universal Pictures

the actors in the studio acting it out. No costumes or makeup, and just a few props at best. Pretty soon after that initial test and rehearsal, the actors had a hard time making that work. You know, it wasn’t exactly motion capture, but it was more elaborate than normal reference footage for the animators. Ultimately, it got shut down by the actors after the first week. We ended up just doing voice recording with all the actors in the studio with a video camera capturing their facial expressions. That footage was then given to the animators for reference. For me, as an operator, it was very cool experience because we had that lensless camera, which was a tablet with antennas on it, and you’re in a room with tracking cameras, so you get to see the rough animation on the tablet and can move around to change the camera angle in real time while the characters were moving in the scene. That meant I could give a scene a handheld feel or do a crane shot just by lifting the tablet above my head. You could do all this cool stuff and Gore and I and the producers would go up to ILM every week and talk to those guys and give them my recording from the lensless camera so they could build it in the finished animation. It was special! I did exactly what I do all the time: I operated as if it wasn’t at all an animated movie.

Gore was a stickler about exactly what the movement should be precisely and how fast, how it transitions into other shots, and we’d have to walk through every step with what was virtually an auditorium of animators at ILM where we would sit every week and have these meetings. We were all part of it, I would listen to what Gore was saying and take notes so I would know how to operate and execute. Needless to say, News of the World was a much more organic way of doing a film, and that’s largely due to Paul, a different director with his own way of thinking and visualizing. Yes, I was content with the visual style at the end. There were the usual tricky parts where the weather was not cooperating or we had changes in schedule, the actors had to go, or we just ran out of time.

CO: I understand that you shot primarily on location in New Mexico back in the fall of 2019. What were the shooting conditions like out there in the desert?

Schaer: I thought the shooting conditions were really inviting. I like New Mexico at that time of year, especially fall into early winter. Once it gets into the winter, though, it gets brutal. We were already encountering snow in November, and it can get brutally cold—the wind on those high plateaus just cuts through you. So, obviously that’s the not-so-friendly side. In terms of shooting locations, currently there are a couple of very usable ranches that have some old buildings and typical

TRIVIA: Wapping, East London is home to both the former office of Rupert Murdoch's newspaper 'News of the World' and a pub called Captain Kidd, named after the Scottish pirate who was executed in there in 1701.

Martin Schaer on the set of NEWS OF THE WORLD with Tom Hanks and Helena Zengel. Photo by Bruce W. Talamon / Universal Pictures

“western towns.” Unfortunately they’re now always used because a lot of westerns are shot in New Mexico. Obviously there’s the landscape, and the amount of sun in that state per year is relatively high, it offers dramatic skies with bombastic cloud formations. Yes, you can encounter monsoon style rains where you have to be careful, other than that there’s rattlesnakes you have to watch out for which means pretty strict regulations for productions depending on the area you’re shooting in. I think the pool of people available in the state, especially based out of Albuquerque, is quite astonishing. There are a lot of people who moved out there, away from the bigger cities, and I have to say I was super happy with my local crew. There were other productions shooting there at the time, but we were able to put a very good crew together with locals for both the first and second units. I have only good things to say; it was a very positive experience. The ranches are private and they are within half-an-hour of Santa Fe, which makes the crew happy because there are good restaurants and culturally something happening there. I don’t mind Albuquerque either— Albuquerque now has studios and they’ve built quite a film metropolis in its own right—but personally I do prefer Santa Fe for production. It’s more pleasant and inviting for the crew. CO: Obviously News of the World finished shooting before the outbreak of COVID-19, but coming on the heels of this world-changing event where people— at best—lost a full year of their lives, I think the movie’s themes of both living in the aftermath of a traumatic event, as well as the feelings of isolation and difficulty connecting with other people in a rapidly changing world, feels all the more resonant. What do you hope is the thing that lingers with people after they see this film? Schaer: Yes, I do hope people pick up on the aspect of racial segregation. I think of great importance is the very fragile situation after the Civil War where everybody is weakened, nobody knows where to go, what’s next. Okay, we know that the war is over, but there’s nothing but misery everywhere. There are diseases, sickness, there’s no money, and everybody struggles to just make it work. In a way it’s amazing that COVID just happened after we shot that film. It’s in a lot of ways a similar situation. Obviously, COVID broke out, it’s not like two parties feuding with each other, even though actually—in this country especially—the pandemic did become so politicized that it ultimately resulted in feuding parties. See what happened between the Democrats and the Republicans. I think that for me, the film did have an ultimate message of human compassion. In the end, The Captain does go back for her, he takes her on. That’s a very valuable point. Yes, it has a happy ending

and maybe in a European movie it would’ve gone the other way, but I do hope that people get that out of it. It’s one of those stories where you take your time to explain the story and a lot of people think, well, this is a bit boring, or this is a little slow, or whatever, so you also have the criticism of that side. Then if you make it faster, it threatens to be solely an action movie and then where do you go with that? In the end it’s a quiet little movie, and at the time I saw it, after Christmas (in a movie house in Montana!), it kind of hit the spot. I think what’s on the screen, is an honest piece of work. Altogether a great, uplifting experience. A big thanks to all the fabulous crew.

MARTIN SCHAER, SOC

Martin was born in July of 1954 in Sion, Switzerland. He studied photography for three years at the School of Applied Arts in Bern Switzerland with an additional three years apprenticing at Schwarz Filmtechnik Motion Picture Film Laboratory. After that, he was the house photographer for Municipal Theater and Opera in Bern followed by three years as a photographer and interior designer for an architectural company in the Middle East. He earned his MFA in Film at the San Francisco Art Institute before spending four years as first assistant camera on music videos, documentaries, television pilots, and feature films. He’s worked as a camera operator and additional unit cinematographer since 1986. Photo courtesy of Martin Schaer

Tom Hanks in NEWS OF THE WORLD. Photo by Bruce W. Talamon

TRIVIA: Paul Greengrass said in an interview in the New York Times on 12/30/2020 how this movie "is the first film I made with a child actor at the heart of it" and he thought that it would be very difficult to cast the role of Johanna but when he saw Helena Zengel's audition, he said she "was the only person I really had to look at" and that it "was the easiest decision in the film."

DAVID DAUT

A writer and film critic for close to ten years, David Daut specializes in analysis of genre cinema and immersive media with bylines at Lewton Bus, No Proscenium, and Heroic Hollywood. David studied at the USC School of Cinematic Arts and currently works as a freelance writer based out of Orange County, California. Photo courtesy of David Daut

Tom Hanks as Captain Jefferson Kyle Kidd in NEWS OF THE WORLD. Photo by Bruce W. Talamon

Live Operating: The Oscars

by David Daut with interviews from: David Eastwood, Lyn Noland, and David Plakos

David Eastwood on the set of the OSCARS. Photo courtesy of David Eastwood

Hollywood’s biggest night is set to return this year on April 25, 2021; a bit later than usual, but with as much of the prerequisite pomp and circumstance as can be obtained given the unusual circumstances surrounding it. Like all live TV, shooting for the Academy Awards, popularly known as the Oscars, presents a unique challenge for camera operators who have to at once clearly convey the “story” of the evening’s proceedings as well as be ever vigilant to capture unexpected moments of spontaneity. Prior to this year’s Academy Awards ceremony, we spoke with three operators about their times working on the biggest event of the awards season.

DAVID EASTWOOD

Camera Operator: How did you get your start as a camera operator and when did you start shooting the Oscars? David Eastwood: In the Live TV article featured in the Fall 2020 issue, I gave a brief rundown of my camera beginnings. In short, my brother-in-law started a production company in Orange County, California focusing on surfing, skateboarding—essentially the sports that now make up the X-Games. They needed a camera operator, and since I had always shot stills and super 8mm, I was hired. It was physically hard work back in the 1980s, with heavy cameras and schlepping a record deck along with it. With no formal training, I did well and received a lot of “Attaboys”—I couldn’t believe they would pay me to operate a camera, it was the best job ever. Mostly I enjoyed it because it didn’t require a lot of math.

I was first hired by director, Jeff Margolis for the Academy Awards after having worked with him on a few earlier projects. What he found

interesting was that I had developed a zoom/focus system that I could operate myself with no focus puller which enabled me to be in the set and have the freedom to move like a handheld camera operator. I believe his thinking was that it would add a more up-close and personal look and feel—anything to set his show apart from previous telecasts. That was early 1990s, since that time there has been a Steadicam or three used on every broadcast since. I have been fortunate to be a camera operator on the show for 24 years straight with 2021 making 25; the first 19 of those was as a Steadicam operator. In 2016, I hung up the Steadicam vest and have been operating my other various robotic cameras: Tower Cam, Remote Heads, RailCams, etc.

CO: How does operating for the Academy Awards compare to other live TV work you’ve done? What are some of the unique challenges?

Sometimes referred to as “Hollywood’s Super Bowl,” the Oscars have a feel of utmost prestige and honor over the other award shows. Every year they remind the audience of the millions of viewers worldwide that are tuning in LIVE! (Which means for the camera operator, if you mess up a lot of people are going to know—but more importantly your colleagues.) The Academy Awards certainly goes to the top of your credit list on IMDb. It’s a show that you want to be invited back on no matter who the director. I would say that most crew members never forget working on their first show.

CO: Though not necessarily scripted, the Oscars at least broadly follow a planned structure. As an operator, how do you find the balance between covering the planed aspects of the show with being ready for unanticipated surprises?

Eastwood: In that regard the Oscars are a lot like many other awards shows, albeit this one is a minimal three hours. It’s important to fight fatigue for sure. No matter how many times nominees are reminded to keep acceptance speeches short or told how to make it to the stage when they hear their name, in many cases, they enter serious brain fog. To anticipate changes takes training and perhaps a sixth sense. It’s the reason why the entire crew specializes in live, award show broadcasts. It’s particularly challenging for the handheld and Steadicam ops when four, five, six nominee live shots are all needed at the same time, sometimes we are all stacked on top or beside one another in an aisle. At a moment’s notice, all hell can break loose when they announce the winner. Think Cuba Gooding Jr. in 1997, or Roberto Benigni in 1999.

CO: Are there any moments that stand out to you as particularly memorable in your time working on the Academy Awards?

Eastwood: During my time as a Steadicam operator, I was always positioned in the on stage right wings where the stars would gather before each award and exit after each winner. I would be in a unique position to hear their chatter before and after each award and before they entered the off stage press gallery. One year, Jack Nicholson asked us if he could help my utility, Charly Fernandez, with coiling the cable attached to our camera. Of course, we said yes. Surprisingly he stayed for a few awards in the wings helping us (or getting in the way), and when it was his time to present he said, “Thanks for letting me help and I’ll see you on stage.” I don’t believe Charly put Jack on his utility backup list.

When Martin Scorsese was in the wings with us he asked me, “How the hell do you hold that thing (Steadicam) for three plus hours? I need to have you on one of my films.” I’m still waiting for his call.

Meryl Streep, one year after she had won—I think—her third Oscar, was very shocked and nervous when she exited the stage. We carried her off into the wings on camera and when the director cut away she asked if she could sit down in my chair for a few minutes before she entered the press area. We gave her a water bottle and she stayed for a few minutes to catch her breath and relax. I believe she referred to the pressroom as the “lion’s den.” Guess you never get used to it.

Halle Berry was in our off-stage right wing preparing to go on stage to present the best actor award. Her instructions were to follow me to the center stage microphone. I asked her once she arrived to give me a chance to loop around her and exit before speaking. I was about two feet away from her talking with 30 seconds to go and she asked me, “How do I look?” I was a bit taken aback and at a loss for words. All I could do was give her a thumbs up, and we were off.

CO: This year’s Oscar ceremony will be the first major award show since the start of the pandemic to be presented in-person rather than having participants and attendees teleconference in remotely. What are the logistical realities of preparing for a production of this scale during these waning days of the pandemic?

DAVID EASTWOOD

Photo by David Levisohn

David Eastwood has worked for 35 years as a camera operator with most of his credits as a full-time Steadicam operator for live TV. He has won 15 Primetime Emmy Awards with over 50 nominations. He was the first owner and operator of a Jimmy Jib camera crane and an early innovator of a zoom/focus handle control for Steadicam. He also incorporated several new technologies for live TV during the late 1980s including onboard program monitors, Tally lights, Prompter monitors, and single pole resting stands (Moses pole).

Eastwood: The logistics are still being worked out for this year’s telecast with regards to the crew. I was contacted a few weeks ago to provide a number of robotic cameras for the show as it allows for remote operation. Obviously, having six-to-eight handheld and Steadicam operators crammed in each isle within feet of each other and the actors might not be happening this year. Think long lenses, robotic cameras operated from afar, and a mix of remote locations all wrapped around a home base set at some theater or other venue.

The in-your-face close-ups, pizza delivery, and world famous selfie moments won’t be re-enacted anytime soon. All those acts of spontaneity made all the better because they were all live in front of millions of TV viewers from around the world. And we as camera operators get to see it first.

LYN NOLAND

Camera Operator: How did you get your start as a camera operator and when did you start shooting the Oscars?

Lyn Noland: When I was in college, a friend—a soap opera actress— knew I was interested in camerawork. She knew about studio television cameras and suggested I try one out. This was easier said than done because, at the time, very few women—if any—were camera operators. I volunteered at a tiny cable station in Manhattan and the minute I got on a camera, I fell in love.

I started shooting the Oscars in 1997 when the director Louis J. Horvitz brought a number of New York area camera operators out to Los Angeles to shoot the show. I was ecstatic. I started on a handheld camera shooting the nominees.

CO: How does operating for the Academy Awards compare to other live TV work you’ve done? What are some of the unique challenges?

Noland: If you are a star-struck film buff as I am, there is nothing like the Oscars. Because the outcome is unpredictable, and the audience is worldwide and in the millions, there is more pressure than the usual TV show. We are put through our paces. If the nominee you are covering wins, you carry them up to the stage, then you need to quickly get a reaction shot from their significant other, or fellow actor, or the director. Preparation helps. If you know the films, the actors, directors, the others involved, you can react quickly and get the relevant shots. There’s a surprise element not present in most other TV shows. As a camera operator you need to have a sixth sense of what’s happening around you. This requires listening carefully and reacting instantaneously.

One unique challenge for me was learning how to walk backwards down the aisle, keeping the camera steady, with the winner coming at me, sometimes running!

CO: Though not necessarily scripted, the Oscars at least broadly follow a planned structure. As an operator, how do you find the balance between covering the planed aspects of the show with being ready for Noland: It is thrilling to react fast, have a shot in focus, and capture a moment you’re sharing with millions worldwide. One year I covered The Lord of the Rings director, Peter Jackson. That year, he won. After carrying him to the lip of the stage I went back and had multiple reaction shots. Mostly there was a fast pace and quick resets. The balance, if any, was in the pause between awards, and the shot of my next nominee.

CO: Are there any moments that stand out to you as particularly memorable in your time working on the Academy Awards?

Photo by Rob Paine

LYN NOLAND

Lyn Noland is an award-winning, New York-based camera operator whose career has taken her across the United States, throughout Europe—and into nearly every television genre across the spectrum. Noland began her career more than 30 years ago in the hectic world of New York news. She has since gone on to shoot primetime specials, scripted series, network documentaries, and stand-up comedy specials with the likes of Dave Chappelle and Chris Rock. Noland is a favorite among directors of live award ceremonies. Such events include 20 Academy Awards as well as multiple Tony Awards, the Kennedy Center Honors, the Mark Twain Prize, Showtime at the Apollo, and The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Inductions. She shot and won an Emmy for Jesus Christ Superstar Live. Noland has also been behind the camera for such legendary musicians as the Rolling Stones, Taylor Swift, Lady Gaga, Elton John, and Bruce Springsteen. She has also shot the Superbowl Halftime Show eight times. As one of television’s most accomplished camera operators, Noland has won six Primetime Emmy Awards and garnered more than 58 Primetime Emmy Award nominations.

This is David Eastwood operating at the 84th ACADEMY AWARDS (2012) as Gwyneth Paltrow and Robert Downey Jr. present the award for Best Documentary Feature. Photo courtesy of David Eastwood.

Noland: Out of so many memories, one of the funniest is a rehearsal of Celine Dion singing My Heart Will Go On from the film Titanic. At rehearsal, she started singing, and, at the same time, the special effects team started pouring what turned out to be too much fog and haze onto the set, which escaped from the set into the theater. In moments, the entire theater was covered and nobody could see. We had to stop down, and everyone was laughing hysterically.

I have fond memories of the generosity of the more experienced operators, sharing their knowledge and how they shot the Oscars. Walking backwards was one of the skills I learned from them!

CO: This year’s Oscar ceremony will be the first major award show since the start of the pandemic to be presented in person rather than having participants and attendees teleconference in remotely. What are the logistical realities of preparing for a production of this scale during these waning days of the pandemic?

Noland: After 25 years of shooting the Oscars, this will be only the second Oscars I’ll miss. The reason is the pandemic, and I trust all appropriate protocols will be in place.

DAVID PLAKOS

Camera Operator: How did you get your start as a camera operator and when did you start shooting the Oscars?

David Plakos: I started my professional career at WDAY TV in Fargo, North Dakota in 1973. My first Oscars show was in 1993 at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles.

CO: How does operating for the Academy Awards compare to other live TV work you’ve done? What are some of the unique challenges?

Plakos: The Oscars is TV “royalty," and the annual production reflects this no matter who the director might be. It is always treated with tremendous respect and the crews assembled are highly seasoned industry professionals who all bring their A-game. Being a live show, all departments must prepare for the “what-ifs" without stifling their creative contribution. I've operated various cameras over my 28 consecutive Academy Awards from handheld, to pedestal, to Jib, and most recent years, the front of house Techno-Jib. Each position requires a different skillset and proposes its own set of “what-ifs." For instance, when operating the Techno-Jib, I must be keenly aware of my fellow operators under my "arm" and not just their physical location for safety but also the angle of their shot coverage so I don't go floating through their shots on the air! I also have to be cognizant of the lighting so as I am swinging a 24-foot arm around or telescoping in towards the stage that I'm not casting any shadows on the talent or set. Even if the shadow is not in my shot, it might be in subsequent shots. Running such a large and moving piece of equipment, I always default to camera moves that are safe—keeping in mind, not just my fellow crew members’ safety, but also that of the audience who really isn't paying attention to me and what I'm doing.

CO: Though not necessarily scripted, the Oscars at least broadly follow a planned structure. As an operator, how do you find the balance

Plakos: Most, if not all, directors call their "show" from an extensive script or expanded rundown which for the most part has every cue scripted (or otherwise) in it. All operators use a camera rundown (paper or electronic) which reflects the order of the live show. During camera meetings and rehearsals, we take our specific notes on these rundowns. For instance, for the Techno-Jib, when should I offer up an extreme wide floating shot for a lighting, scenic or pyro cue or which way should I be headed on a camera move as talent is entering on stage from stage left or stage right? In the past, I've worked with directors who have scripted and numbered every shot but most directors now assign specific "zones" of coverage (head-to-toe or close-up among others) which we don't deviate too far from. As operators, we have the flexibility and responsibility to frame up what we believe is the best shot that the director has requested and they rely on us to do this automatically. As always, you must be prepared for those "unscripted" moments and be able to offer up your "zone" coverage for any surprise.

CO: Are there any moments that stand out to you as particularly memorable in your time working on the Academy Awards?

Plakos: The moment that sticks out the most to me was during the 1999 Oscars where I was operating a handheld camera, shooting nominees in the audience at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. The award category was for Best Foreign Language Film. My nominee was Roberto Benigni for Life Is Beautiful. When presenter Sofia Loren announced that Roberto had won, he immediately and quite unexpectedly kicked out his leg hitting my lens and jumped up onto the back of the seats in front of him grabbing the extended hand of one Steven Spielberg who offered up assistance to steady the newly named Oscar winner. Roberto then proceeded to "hop" up the steps to the podium and joyously went on to embrace Sofia on stage. He was quite overwhelmed and appreciative and gave a very inspired, touching, and humorous acceptance speech.

CO: This year’s Oscar ceremony will be the first major award show since the start of the pandemic to be presented in-person rather than having participants and attendees teleconference in remotely. What are the logistical realities of preparing for a production of this scale during these waning days of the pandemic?

Plakos: Our industry, from executive producers on down, have taken the COVID-19 protocols for talent, staff and crew very seriously (I've personally been tested close to 100 times). All award shows that I have been on during the pandemic have followed strict precautions for all crew. Whether there are in-person attendees or not, there are still a lot of men and women gathered in one area working and safe distancing; masks and sometimes face shields are part of the “uniform of the day.” Some camera positions that are usually manned are now replaced with “remote heads” with the operator in a different part of the stage or another room, thus keeping the amount of human contacts on or near the stage to a minimum. Recently, I ran such a remote head at the Grammys which did have in-person attendees and production employed strict COVID testing schedules and protocols for talent and crew. I know the Academy Awards will be no different. My sincere thanks to all the production companies who endeavor to keep us all safe as possible.

Photo courtesy of David Eastwood

Plakos operating at the Techno-Jib center of house at the 2020 OSCARS at the Dolby. Photo by Brian Bowen Smith. Headshot courtesy of David Plakos.

DAVID PLAKOS

David Plakos is a Los Angeles-based freelance camera operator. He's shot hundreds of music/variety television specials, concerts, and award shows—specializing in live events, as well as multiple TV series.

Plakos has 49 Emmy Award nominations and has won 10 Emmy Awards. He has also served on the Television Academy's “Lighting, Camera & Technical Arts” Peer Group Executive Committee multiple times, and is currently co-governor.