6 minute read

Five sisters & a family tree by Elizabeth Moignard

FIVE SISTERS & A FAMILY TREE

The image of Susan’s work which sticks in my head from a visit to a local gallery is a life-size sculpture of a lamb, posed nervously and slightly awkwardly, as if for take-off; a facial expression which I would read as nervous, if not fearful, with intense dark eyes, and widespread ears. The lamb’s fleece has patterned interventions – a partial mosaic of fine textile or tile-like areas on its back. Not far away is a badger sitting up, with a checked breast and underbelly, countered by incised fleur-de-lis patterning over its shoulders, and a disconcerting trail of red down one side of its back. Both animals expect a very intense engagement with their viewer: they look you in the eye, and expect to be invested with a personality or an interpretation of their expression and stance: Susan’s own artist’s statement, and a conversation with her, confirm that this is her working intention – we tend to invest these creatures with a personality which originates in our own, and probably do the same with living creatures too, whether observed in passing, or much loved pets with habits which we have time to notice, and think we understand.

Advertisement

There are many representations of animals in Glasgow’s art collections, both public and private. Not all of them feature as the prime focus of the image, but it is an interesting exercise to go and see what you can find, even as incidental appearances. The Hunterian collection has two 17th century Dutch group portraits with a pair of spaniels having a growly spat at the front – I had not noticed these until I went to look – they are a small feature and one tends to look over their heads. Not far away, though, is Stubbs’ wonderful mood statement about the Moose, a gloomy animal exuding intense depression in a miserable landscape: a postcard I used to send to fellow sufferers in exam time. The city’s public collections feature animals as the primary subject sometimes – highland cattle are naturally a part of the national agricultural landscape – but few if any thoughts about the Burrell Collection seem

to notice how far animal art figures as a key theme, from cheeky sheep in a mediaeval tapestry to two ancient Greek Minotaurs, to many horses racing and working, Chinese dogs and lions, a strutting cockerel in a Roman mosaic. You notice that I am, at least partially, reading human interpretations into these images, and also that the collections reflect a local interest which is so embedded that it can pass us by very subliminally.

My first thoughts about Susan’s work were to highlight that local theme, and to reflect on the interest in and commitment to animals and their supposed or observed behaviour and psychology which is so evident in these local collections. So far, so good, and I still think there is an important reflective strand there, but a visit to see Susan in her Glasgow studio at the beginning of what turned out to be a remarkable day

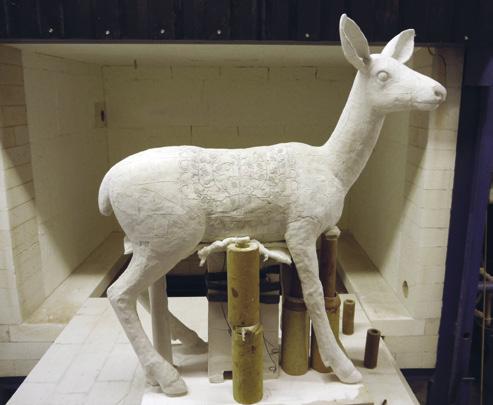

introduced some other thoughts on her work and practice which must gain an airing too. Susan showed me some of the work in progress for this exhibition, in various stages of completion, and talked me through her careful and meticulously slow production process. On the open table in the studio were another lamb, complete with embroidered fleece and an equivocal facial expression, another badger, a guinea-fowl, and some smaller birds. Round the corner was a space with headmoulds, including some scary crows which will be in the show, one of the metal armatures on which the animals are built, and trays of paper clay which will form some of the surfaces. I was also shown some of the laser-cut stencils which are used to create the very complex patterns on the paper clay. Gradually I was allowed to form a sense of a making idiom in which the armature is invested with stoneware and then a porcelain layer, which will take the partial patterned surfaces and acquire texture and colour.

The meticulous attention to the details and making process are a key element of Susan’s practice – it takes time, intense care and precision, and the outcomes are personal and tactile. Susan told me something about the people who inspired this show: the five sisters of a previous generation of her Irish-German clockmaking family, whose love of textiles, embroidery and tapestries fed into Susan’s use of pattern, and the evidently inherited commitment to detail and taking time to achieve an impressively high level of fabrication quality. A conversation followed about both our families’ female members, and their particular sets of hand-skills and making pleasures, which were both taken virtually as a given, and part of domestic creative practice, whether or not they contributed or cross-referred, as my mother’s did, to a professional one: her surgical activities were surely underpinned by capacity as a metalsmith, a tailor and a carpenter. Susan clearly carries her family’s making genes; I rather doubt that I would make the same claim, and I think that as a generation, we tend to assume that many of these making habits and pleasures are much less common than they used to be.

That said, later the same day I travelled home with two distinguished female professors, one an engineer and the other a cultural sociologist, from a ceremony in which they were being inducted as Fellows of a major learned society. I had told them about my visit to Susan’s studio, and we were soon talking about female skill sets; as we talked, the sociologist got out a sock which she was knitting for her husband in traditional fashion with four needles. I told Susan about this later, and she said that she also enjoyed knitting or crochet on public transport. A cheering final note to a complicated day with many strands of thought which came together in an unexpected finale. And I arrived home to find our small tortoiseshell cat sitting at the top of the stairs, looking at me climbing them with wide dark eyes in the shadow, and spread ears, very like Susan’s lamb.

Elizabeth Moignard June 2015