5 minute read

Institutions Don’t Care

Racism Built The Education System and Institutions Don’t Care

A chat with two Black locals

Advertisement

FEVEN KIDANE Contributor JOWAYNE MCFARLANE Illustrator

“People always have something to say when Black people stand up for themselves,” said Kamika Williams, co-founder of Anti-Racism Coalition (ARC) Vancouver.

At the time of this interview, ARC Vancouver was in the midst of planning the first-ever Black Shirt Day, in which black shirts are worn to acknowledge the inequity Black Canadians (and beyond) face. The date of such awareness was Jan. 15, the birthday of Civil Rights Movement activist Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., a hero for many Black individuals, including Williams.

An idea thought of with anti-racism in mind, ARC Vancouver had been in consultation with individuals across the country to execute a plan inspired by Orange Shirt and Pink Shirt Day. To accompany the permanence of Black Shirt Day will be formal education in Black history as planned by Black educators gathered by ARC Vancouver, coming in 2022. “The most important thing about Black Shirt Day is getting mandatory curriculum in BC schools,” explained Williams. “If Black Shirt Day is mandatory in schools, then the education behind it is mandatory as well.”

Picking a day the world would recognize, Williams felt Dr. King Jr’s birthday was the perfectly-timed choice, especially since it was two weeks before the start of Black History Month in February. With the concept of teaching at the forefront, she knew that the bridge into the weeks to come would feel natural. “It’s just a great way to start that conversation and keep it going and open the door to have a more robust mandatory curriculum,” she stated.

Similar to many other Black folks raised in Western Canada, Williams was one of few Black-presenting children in elementary and high school in her hometown of Victoria, BC. During those years, she was bullied for her race and singled out by peers— not even teachers treated her as equal to her classmates. “I was adultified more than the white girls. I always got in trouble for saying stuff that they said,” she recalled. “I’ve always known from a young age I should be proud to be Black, [but] we are treated differently.”

Williams remembers only one Black teacher throughout those thirteen years of school, something she believes needs to drastically change if there is ever to be actual movement in the fight for racial justice. “[When] you’re experiencing racism, it’s hard to feel safe when the teacher looks like the people who are treating you badly,” she went on to say. To her, the classroom is not a place of acceptance, as it was never meant for the inclusion of people intentionally pushed to the side. Even if the school appears to be inclusive, the systematic oppression and omission of equitable life and class lessons runs through the veins of education in trickle-down fashion. “Everybody who has [run] these institutions for hundreds of years have never really looked like us,” Williams stated. “I don’t think these schools were built with BIPOC people in mind.”

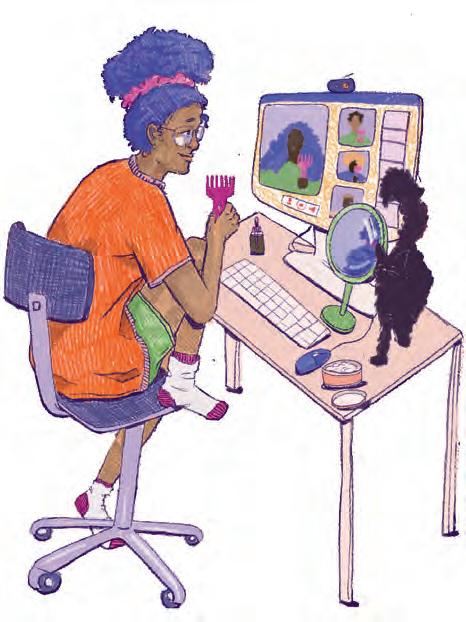

Jamal Foster, a third-year Jazz student at CapU, heard about Black Shirt Day and reflected on the initiative. “I feel it would’ve helped me discover and understand myself on a much deeper level had I been introduced to what I am early,” he noted. “I think a lot of other kids could’ve as well.” Also, growing up Black-presenting, finding the box to fit in comfortably was a challenge. There were times his learning environment only welcomed the white side of his lineage, not his Black side, leading to him being othered.

As he’s grown, the public’s reaction to his skin tone has not changed. When asked how he’d noticed racism towards him as he’s gotten older, he mentioned his ability to recognize it better now compared to in childhood. The identification of racism doesn’t come from flashbacks, but current acts of racism and microaggressions he still experiences. “I faced similar issues then as I do now,” he began, “I would get pulled over by the cops frequently. I'd have people look at me weird cause I don't look like them, especially working in a place like Kerrisdale which is predominantly white, [and] on the older, richer, more privileged level.” The only thing he has been able to do in such situations is wait it out; these harmful actions are, according to him, just part of life as a Black person in a white-dominant area.

When it came to his post-secondary experience, Foster felt isolated. In his eyes, campus exposure to Blackness has been limited due to the University’s disinterest in prioritizing it, a microaggression in itself. “I think that one of the things I definitely notice about our university is the lack of Black celebration,” he shared. “We have nothing outside of the jazz program as a whole that is Black culture related.” The only instance of Black Joy that Foster has seen in his three years attending CapU was last year’s Black History Month Cabaret, planned by the Capilano Students’ Union, which saw Black students meeting each other for the first time. It is no secret that the student body hardly has anyone Black, something Foster believes is related to the University’s failure to actively diversify its practice. “We’re not really that big in support of Black culture and Black history,” he said. “I don’t think [CapU is] necessarily a school that’s that appealing to Black students.”

Foster expressed disappointment at a one-paragraph message written by CapU President Paul Dangerfield, posted last June. He considered it a missed opportunity to acknowledge systemic racism within the school and roll out a plan to fix it. Entitled “Times of Tumult and Tragedy”, the primary focus of the message was the institution’s distaste towards the violently racist American atmosphere.

In Foster’s eyes, this statement was problematically barren, promising nothing. “[People] in the position of power have the ability to do something big, and yet here [they are], not doing anything at all,” he commented. “What exactly has [been] done to show proper support other than a single paragraph email?”

“We’re adults, and we still need to learn [anti-racism].”