9 minute read

Zsudayka Nzinga: Artist, Curator, Educator and Community Leader by Phil Hutinet

The Way Forward to DC

Born and raised in Denver Colorado, people thought Zsudayka Nzinga, was nuts when she told people in middle school that she wanted to move to DC to become a famous artist. Yet it seems that she is on track to prove her critics wrong.

Nzinga attended Hampton University, an HBCU (Historically Black College and University) in Virginia with the intention of studying journalism. During her freshman year, right after the attacks of September 11, she visited DC for the first time attending a seminar at Howard University for budding journalists organized by Hampton University. Nzinga reveals that it was at this moment, “when I first came to DC, I knew I had found home.”

Before getting married to Ward 7 native James Terrell and planting roots in Deanwood, Nzinga moved around a between Denver and Virginia by way of New York City and Atlanta, Georgia. While these moves reaffirmed her desire to become a Washingtonian, at Hampton, she had chosen not to enter the field of journalism. Instead, she chose a path that would lead to a career in the arts. While her artistic practice currently focuses mostly on painting and mixed-media work, Nzinga still maintains a reverence for poetry and spoken word.

In the Gallery: Zsudayka Nzinga. Photo: Joseph Chisley

by Phil Hutinet

Pandemic Process Shift

The effects of the pandemic have had varying impacts on all of us. For artists around the world, the experience has led to creating work that evokes themes of solitude and isolation. In Nzinga’s case, the pandemic has changed the manner in which she explores being a Black woman in America, a central theme in her work.

With two small children and a preteen to raise, before the pandemic, Nzinga would “get to paint in spurts.” However, when schools closed, her husband, who teaches art, stayed home. This gave Nzinga the opportunity to work a couple of hours at a time.

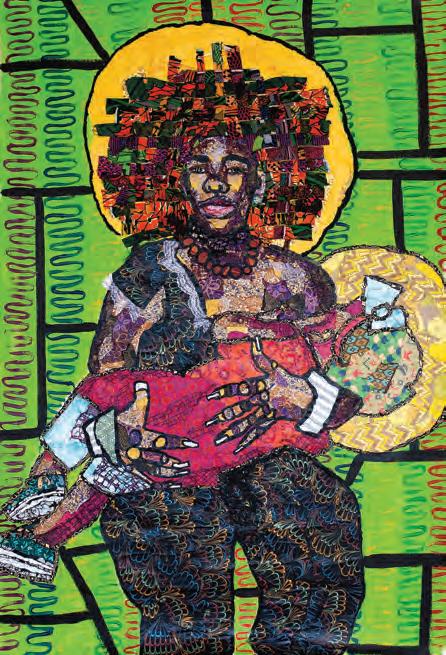

The increase in time allowed Nzinga to delve into collage, using fabric and employing diasporic themes such as braiding hair and textiles. For example, she has been learning about the practice of braiding maps into women’s hair so that they wouldn’t get lost. She has also been thinking about how textiles serve as maps to indicate people’s origins. As her process and use of materials evolved over the past ten months, Nzinga delved deeper into her identity. “I began thinking about [the order of words] American African vs. African American and embracing my identity as an American.”

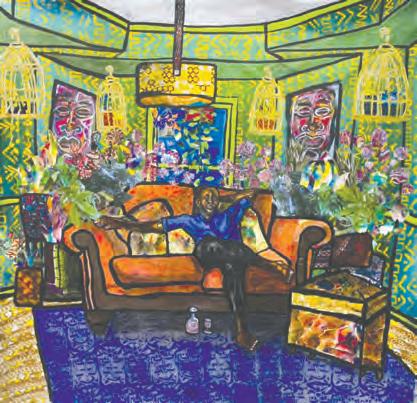

Nzinga sees her American identity as prime while simultaneously acknowledging her African roots and comparing it to how other American groups like Italians talk about their cultural identity through food, culture or religious practices. She further elaborates that “When the hashtag #blackartmatters appeared [over the summer of 2020], it started an interesting discussion of who is an American. As Black artists, we have our own aesthetic but it is an American one.” Nzinga believes that “Art is good because it’s a way to communicate culture without being aggressive. “ As a figurative painter, one of the difficulties Nzinga experiences from isolation is being disconnected from other people and the encounters which provide her with inspiration. “People are my inspiration,” she explains. Her recent work has also addresses the paradox of “watching children playing peacefully at home while watching cities burn on TV.” With parental responsibilities, Nzinga understands that “I am not on the front lines [of the social justice protests] and my work is reflective of that.” So, she has sought to “dig deep politically” to understand how she, as an artist, can contribute to social justice and equity through her work as an artist, curator, educator and community organizer.

Zsudayka Nzinga “Breastfeeding 2”. Photo: Joseph Chisley

DC School Teacher Art Exhibition

Nzinga and her husband strongly believe in the importance of engaging young people in art at an early age. She writes curricula for children’s art programs and seeks to provide

Zsudayka Nzinga “The Red Couch”. Photo: Satra Nudara

youth a path to making a living as artists by organizing exhibitions of their work. Nzinga’s pedagogical philosophy is as poignant as it is simple: “We can’t diversify museums if we tell kids they cannot make a living as artists.”

Nzinga’s husband James Terrell, who is also an accomplished artist, teaches at Friendship Public Charter School which, like all other educational institutions, shut their doors unexpectedly in March 2020 due to public health concerns over Covid-19.

She and her husband went back and forth sharing ideas about what to do about the school closures. They sought a means by which they could engage adults in the same manner they engage youth. To that end, they focused on teachers whom Nzinga considers “unsung frontline workers.” Nzinga recalls that “The school closures were so sudden. Many of the children did not have school supplies,” and teachers helped instruct children remotely by helping children use whatever materials they could to create.

Out of this adaptation, Nzinga decided to curate a teacher’s exhibition to honor their dedication and to showcase their art. The DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities, DC’s state arts agency, o ers an annual grant to applicants seeking to organize an exhibition. Seizing this opportunity, Nzinga wrote a successful grant application which was funded by the commission.

Nzinga explains the process of selecting teachers for the exhibition: “We asked teachers to submit work based on their experience with the pandemic and the social unrest we saw this summer. This is a moment we may never see again in our lives. Artists are historians who can share and document this period.”

The exhibition “pulls together amazing work that tells what the American Experience is and shows what America is going through.” Nzinga also peppered the exhibition with two spoken word artists with whom she has worked in the past, Drew Anderson and Bomani Armah, whose poetry provides verbal cues to better experience the project.

What Nzinga also discovered during this process is that while teachers have advanced degrees in art, many have never had the opportunity to exhibit work. Additionally, thanks to the exhibition, many parents have discovered—much to their surprise—that their children’s teachers are also talented artists.

An Arts Center for Ward 7

Nzinga and Terrell’s decision to move to Deanwood was deliberate. One of the longest continuously occupied Black communities in the United States and in DC, Nzinga and Terrell wanted to “put roots in a community that we could give back to and get involved with.” “When I rst moved over here, I was very impressed by this amazing community rich in culture and lled with talented ne artists,” recalls Nzinga.

Inspired by Anacostia Arts Center in Ward 8, Nzinga would like to create a similar venue in Ward 7, in Deanwood’s commercial corridor. “Ward 7 needs the exact same thing,” she concluded. She has met with area ANCs and other community leaders to start a conversation on how to make this happened.

While the pandemic may have slowed the progress of a Ward 7 arts center, Nzinga nevertheless sees “a unique opportunity.” She believes public programming from a community art center can o er much needed catharsis for the extreme tension and anxiety people have felt over the past year. “A lot of people need to release their emotions. People have not had the opportunity to do that.”

Nzinga also sees an arts community center as bridging the gap between the pandemic and future days when we will no longer have to wear masks and socially distance. “Before this past year, we wanted to get collectors to see local artists,” she recounts. Now she asks “What are some ways to use art to give back to the community?” Some examples she cites are as follows: “We can do food giveaways, hand out diapers and other supplies. We’re refocusing on what Deanwood and ward 7 needs right now even if it’s just painting on the windows or holding a fundraiser for our community to get the things that people need right now.”

Terrell Arts DC: www.terrellartsdc.com

Visit the online gallery for the DC Teachers Art exhibition: www.dcteacherartshow.com

Phil Hutinet is the publisher of East City Art, DC’s alternative art source. For more information visit www.eastcityart.com. ◆

(Continued from pg. 31)

DC Santa and Mrs. Claus

School, spent about a year and half in Quebec before living in West Africa for 27 years. They were assigned to work on a reforestation project because “the Sahara (Desert) was moving further and further south.”

Due to sensitive issues involving religion and politics in the African country where the Haagas performed missionary work, they did not want to identify the speci c nation by name.

The couple, with their two young sons in tow, worked with a small Christian church group of 10 to 20 people while “the rest of the neighbors were Muslim. We became a part of the town’s life and attended the weddings, naming ceremonies for babies and funerals. It was an incredible privilege to be a part of their lives,” Mrs. Haaga recalled.

Coming Back to America

Since returning to the United States and taking up residency East of the River, the Haagas have immersed themselves into their new environment with several activities. Before retirement Elaine worked for a nonpro t, Council for Christian Colleges and Universities (CCCU) on Capitol Hill and “went from sitting on mats in (West Africa) to an o ce on Capitol Hill. That was a big adjustment.”

“Elaine was our Receptionist and Assistant Conference Planner. She cared about people deeply. She was a pillar of our organization. When she decided to retire in 2019 everybody was so sad. When she was leaving, she went out and got a gift for every single delivery person who came by the o ce. She made friends with them,” said Casey Lamar, the then-Director of Conferences and Mrs. Haaga’s former supervisor. “Elaine and Bert are simply cut from a di erent cloth.”

They started a community garden at their home and happily share their fresh produce that includes collard greens, tomatoes and kale with any nearby resident interested in organic vegetables that are free from unhealthy additives and preservatives. Canning and sharing vegetables are methods used by the Haagas to formulate close bonds with neighbors.

“One of the reasons we moved here to Southeast was because we thought we could really get involved in the community and help heal racial issues plaguing our country,” Mr. Haaga said. The Haagas say they love living in the District and particularly East of the River. They’re happy that their history of forming friendships internationally is now continuing in Ward 8. ◆