8 minute read

Much Accomplished, But Much

A Message from Tommy Wells, Director, Department of Energy & Environment

blinds,” etc., said Charlotte Dreizen, a former program analyst with DPW’s Office of Waste Diversion and now a sustainability manager for a DC-based trade association.

The crews either accept or reject the pile on the tipping room floor. If the load is acceptable, the crew transfers the recyclables into a larger, privately-owned long-haul truck for a 24-mile journey north on Route 95 to a processing facility owned by Waste Management (WM) in Elkridge, MD.

“For any given load (of recyclables on the tipping room floor) that has more than 20 percent contamination, the entirety of that load will be moved to the trash pile, as recycling facilities can’t handle an infinite amount of contamination.” said Dreizen. All trash is later placed on another DPW truck for a trip to either one of the city’s landfills or the Covanta waste-to-energy plant (incinerator) on Furnace Road, in Lorton, VA.

“Typically, they (DPW employees) see loads that are pretty good, though there are no official agency numbers,” Dreizen said. “A couple of times a day if a load of recycling comes in at 50 percent contamination, the contract with WM dictates that WM can reject it. So rather than taking it to Elkridge and wasting money on time and gas, plus polluting the air with the truck’s emissions, they just throw it in the trash.”

To that point, Neil Seldman, director of the Waste to Wealth Initiative for the Washington-based Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR) estimates that 20 percent of recyclable loads tipped out on to the floor at Fort Totten are found to be contaminated.

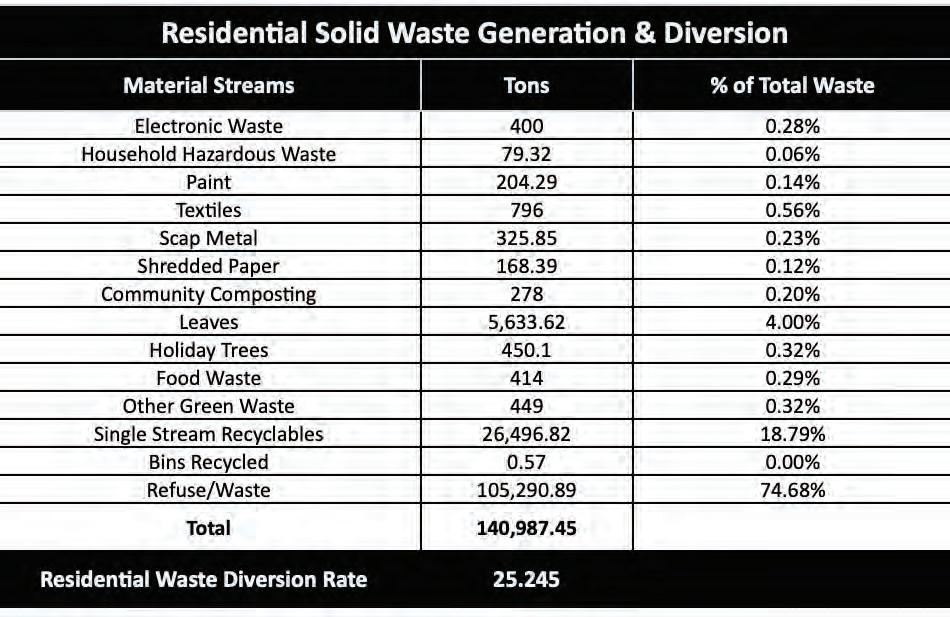

DPW was unable to confirm Seldman’s and Dreizen’s statements. However, statistics of recycling can be gleaned from the DC Council’s Committee on Transportation & Environment’s Oversight Committee’s DPW hearings: In particular, the agency reported the recycling diversion rate for DPW residential collection for the past four fiscal years. The rates were: • FY 18 – 25.24% • FY 19 – 25.1% • FY 20 – 25.0% • FY 21 – 23.9%

The recycling diversion rate is defined as the weight of diverted waste (recyclables) divided by the weight of all waste then multiplied by 100. So, over the last four fiscal years the diversion rate for residential trash pickup has fallen 1.34 percent. Not a positive trend. (https://zerowaste.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/zerowaste/CY%2018%20Diversion%20 Report%20Final%203%2010%2021.pdf).

DPW has not published an Annual Waste Diversion Report since 2018 (see the adjacent table). In that year, DPW collected 140,987.45 tons of solid waste from the curbside and at community drop-off locations. The largest portion of this, 18.79 percent, were “single stream recyclables.” Singlestream recycling is a system wherein recyclables, including newspaper, cardboard, plastic, aluminum, etc., are placed in a single bin for pickup by a truck to be sorted later.

At the time of its most recent DC Council perfor-

Much Accomplished, But Much More to Do

As we approach Earth Day 2022, I pause to reflect upon our work over the past five or six years at the DC Department of Energy & Environment. It is a privilege to work with so many smart and dedicated people devoted to restoring and protecting the natural health of our city. And there have been some surprises along the way.

The first is the prediction of a rapidly changing environment due to global warming has happened far faster than I could have imagined. Our city is experiencing unprecedented flooding and high heat for longer periods putting many of our residents and Important city assets at risk. While I am proud DC is leading the nation in implementing innovative programs to mitigate climate change, there is always a sense that it is not nearly enough. It is clear we must focus on adaptation and resilience in the face of major environmental change. The climate has already changed for the world and our city must prepare for what is to come. The team at DOEE has made this task its primary focus. The second surprise is found in the results of all the efforts we are making to restore streams, eliminate toxic pollution, prevent our sewer systems from overflowing and restore natural habitat throughout DC. We have seen nature do its part meeting us more than halfway in repairing natural habitats.

Eagles, ravens and other species of birds not seen in nearly 100 years have returned to the city. Beavers and other wildlife are returning to our rivers as well. This is a miraculous phenomenon to observe as we restore nature to DC.

We have made substantial progress as a city implementing new green infrastructure, deploying solar energy and cleaning up our waterways. Much of this has been accomplished because of the support of our residents and the resources made available through our tax dollars. On this Earth Day we know we have done much to lead the nation, but we also know there is so much more to be done.

DCGre n n

mance hearing, the agency testified that 2021 Diversion Report had been completed, but not been released. The report had not been published at the time this article was written. At a late March 2022 roundtable presided over by Ward 3 Councilmember Mary Cheh (D), Seldman and other veterans of the DC recycling industry all expressed frustrated by the DPW’s lack of transparency when dealing with the community.

The national average recycling diversion rate is somewhere between 32 and 35 percent, stated Seldman. “A strong figure would be about 45 percent, he added. Cities such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, Portland (Ore.) and Bethlehem (NY) “are all at or above 70 percent. Any city that is doing well is at or above 40 percent,” Seldman pointed out.

So, what happens to the recyclables deemed sufficiently uncontaminated enough to process at Elkridge?

Processing Recyclables

At WM’s facility in Elkridge, the materials are weighed, dumped on WM’s own tipping floor, where they are evaluated again for contamination. Those that are accepted are moved to a conveyor belt. Line workers shuffle through the items in the facility’s pre-sort area. They remove everything not recyclable such as dirty diapers or soccer balls. Most importantly, they toss out those ubiquitous plastic grocery bags along with their contents. DC’s recyclables are then comingled with those of other jurisdictions. Recyclables at Elkridge are made up of: 40% - plastic, glass, aluminum cans and bimetal cans; 35% - corrugated cardboard ; 25% - other paper products.

After sorting the recyclables with its various machinery, WM bails the materials to sell as a commodity at market price. “One day, it may be purchased by a company in North Carolina, another day by a company in the Midwest,” said Dreizen, “and still another day by one of WM’s international clients. It depends on the market and quantities.”

Twice a year DPW and WM cooperate to measure percentages of glass, paper, cardboard and contamination in DC’s recyclable stream, Dreizen said. “It’s usually a couple of people who make the trip from DPW to see the material that it is managing.”

While the DC recycling rate stands at about 20 percent for cans, bottles, cardboard and paper products off to the trash pile, according to the DPW and to ILSR, “the amount of material in the general waste stream is much more than that,” he said. “Many plastic soda bottles, for instance, are in the regular trash, which is why DC has a very low recycling rate compared to other cities.”

For its part in this equation, there has been much turnover in recent years at the top spot at the DPW, which some observers point out as part of the issue.

A request by Hill Rag to interview current DPW Solid Waste Management Administrator Valentina Ukwuoma, who oversees recycling, was declined. Blake Adams, manager of the DPW’s Office of Waste Diversion, did respond to an interview request, after DPW public affairs initially answered most questions regarding this article via email. All of DPW recycling residential efforts will remain ineffective, however, if the public does not understand what to and what not to deposit in the agency’s blue bins.

Public Ignorance

Though the posted rate is 20 percent, “I estimate that about 50 percent of the cans, bottles and paper products in the trash stream are recyclable,” said Seldman, but do not end up in the blue bins “due to the lack of recycling culture and incentives in the District.”

“Nor are they doing three things they need to do,” he said. “Raise public awareness efforts with bus and train ads, flyers, newspaper ads, etc.; start a school education program with re-

After it’s bailed, recycled product at WM is loaded onto trucks and sold on the open market. Photo: Mark R. Smith

cycling-based curricula and industry internships for high school and junior college students; and create incentives to recycle, like unit pricing for garbage collection which is used in thousands of US cities. That can increase recycling by about 40 percent.”

Wish Cycling

Whatever the numbers, there is one major issue that stems from the general public’s need for more information,

WHAT NOT TO RECYCLE

What does not go in your blue recycling bin?

• Recyclables in plastic bags • Plastic bags, period (take them to your local grocer) • Plastic film • Plastic wrap • Batteries and electronics • Clothing and shoes • Food waste • Food-soiled plastic/ paper containers • Glass • Paint and other household hazardous wastes • Plastic window blinds • Scrap metal, wood and furniture • Styrofoam • “Tanglers,” like hoses, wires, cords and holiday lights • Textiles, clothing and linens • Wet cardboard/paper • Yard waste, wood, flowers

At http://zerowaste.dc.gov, users can type the name of an item into a search bar and see if it can or cannot be accepted.