7 minute read

Wisdom and Ways with Jim Casada

Wisdom and Ways

Traditional Winter Foodways

By Jim Casada

In today’s world, the average High Country resident gives little thought to winter food preparation. Meals are as close as the nearest grocery store or maybe even a delivery service. About the only deviation from that comes when an impending spate of snow or ice throws a kink in things. Then there’s a brief but powerful reminder of times when folks were self-dependent, food-wise and otherwise, to a degree that is now unknown. Yet it behooves us to look back on this largely lost world, one where “make do with what you’ve got” and “raise what you eat” lay at the very heart of mountain existence.

A logical beginning place was with a staple that could almost be described as the mother church of culinary considerations in Southern Appalachia—corn. There were actually two basic types of corn, sweet corn and field corn, with the former being a garden item while the latter was normally grown in separate patches, often in tandem with October beans and pumpkins in the traditional “three sisters” approach. Sweet corn was eaten on the cob as roasting ears, cut from the cob for creamed corn or use in soups, and canned.

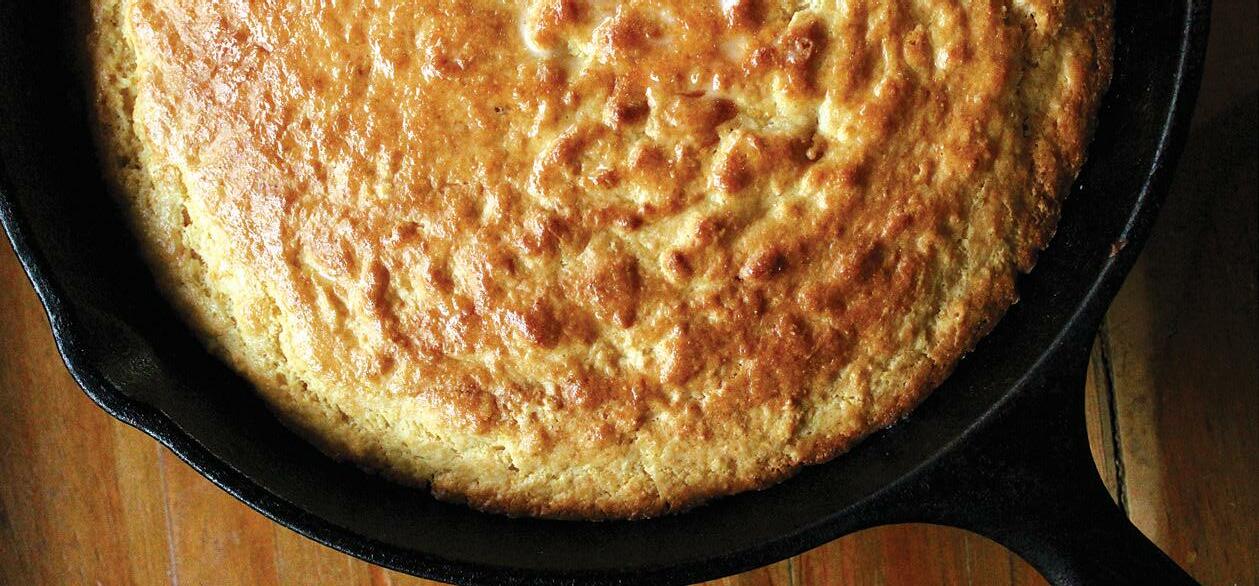

Field corn was in large measure a dried food, inasmuch as it was allowed to mature on the stalk before being harvested. It could then be stored in a crib until needed for a run of cornmeal at the nearest miller’s place of business or used in other ways. The dishes provided by corn were in some senses limited by nothing except a cook’s ingenuity. There were hominy and grits made from kernels that had first been processed with lye made from water and wood ashes to produce those delicacies. Festooned with a pat of home-churned butter, either made for mighty tasty eating. Corn ground for meal produced cornbread, fritters, hoe cakes, johnny cakes, hush puppies, and other treats. Many a mountain youngster carried a bucket lunch to school featuring a chunk of cornbread and maybe some molasses to enhance its taste. Cornbread and milk were standard fare, maybe with a piece of fried streaked meat as a side, for supper.

Then of course there was consumption of corn in a somewhat disreputable manner—its liquid form. Variously known by colorful descriptions such as tanglefoot, golden moonbeam, peartening juice, and snakebite medicine, moonshine was for some folks an integral and important part of mountain life. Illegal distilling and bootlegging have garnered far more attention and notoriety than they merit, but by the same token there is no denying they were widely practiced by certain segments of High Country society.

Dried legumes of various types also figured prominently in winter diet. Soup beans (a generic term for various types of beans including pintos, navy beans, kidney beans, October beans, and even field peas), invariably served with freshly baked cornbread, were a standard on mountain tables. So were leather britches, the colloquial name given to dried green beans. They would be harvested, washed, and strung. Then came the drying process. It usually involved using a heavy-duty sewing needle and some stout thread to place long strands of them on the string for drying. After hanging for several days in the summer sun, an outof-the-way kitchen corner, or from rafters in a tin-roofed barn, they would become leather like in appearance and would keep for months. All it took to prepare a mess of leather britches was to reconstitute them with a suitable amount of water in a pot, add some streaked meat and maybe a few flakes of dried hot pepper for seasoning, and set them to cooking.

Dried fruit also had considerable significance. Most mountain families living off the land had small orchards with peaches and pears, but especially apples, growing in them. Peaches and apples, when harvested, sliced thin, and dried until just short of brittle (sometimes with a bit of sulfur to prevent browning and rot), could be stored in cheese cloth in a warm, dry place, such as the corner of a kitchen with a wood-burning stove, until needed. They formed the basis for cherished traditional High Country sweet treats such as mule ears (fried pies) and that quintessential regional dessert, a stack cake. Reconstituted with a bit of spice added, along with sorghum molasses as needed, dried fruit was the answer when it came to satisfying a sweet tooth. Of course various offerings from orchards, along with tame and wild berries, were also preserved for winter use as jams, jellies, butters, or fruit leather.

When it came to meat on the table, pork took pride of place. Among other domestic meats, a common description for chicken, “preacher meat,” pretty well tells the tale. It was reserved for special times, such as when a local minister or perhaps family from a long distance away came to visit. Chickens were too valuable as egg layers to be utilized on an everyday basis. Beef was a

Continued on next page

comparative rarity, as was mutton. Indeed, on many mountain tables, and that would have included the one at which I dined as a youngster, the second most common meat after pork was small game—squirrel, rabbit, ‘coon, grouse, or quail. Deer and turkeys were exceedingly scarce and for generations weren’t part of the typical mountain culinary picture.

Pork had many virtues. Pigs required relatively little space, could be allowed to range free in the fall to fatten up on chestnuts (prior to the devastating blight around 1930), beechnuts, and acorns, and were far easier to preserve than other meats. Everything from hams to side meat could be cured, sausage or even prime cuts could be canned, and pork was as versatile in the meat line as corn was when it came to vegetables. Hams and slabs of bacon hanging in the family smoke house or cannery were a comforting sight with winter coming on and the same held true for shelf after shelf laden with canned goods.

Canning was, for some three generations from around the turn of the 20th century until the widespread transition to freezers, the favored approach for food preservation. Even today— even with the ready availability of foodstuffs from grocery stores, decline in reliance on home gardens, and roomy refrigerators with considerable space for frozen goods—canning remains of importance to many mountain folks. That is particularly true during winter months, when canned goods from efforts tracing back to months of crop growth and production await sampling and savoring. Adding to their appeal is the fact they form a tangible, tasty link to foodways of the past. There’s just something about opening up a quart jar of fruit or vegetable soup mix that lifts the spirits and whets the appetite. Similarly, anyone who still enjoys the culinary wonder of pork sausage fried in patties and sealed in jars with lard knows canned goods readily translate to table magic.

This all harkens back to a time of simpler days and simpler ways, but rest assured that when it came to foodstuffs, hardy, self-sufficient mountain folks knew how to confront winter’s bitter weather with scrumptious fare.

Banner Elk Winery & Villa

Experience Luxury in the High Country’s Original & Most Acclaimed Winery

Savor award-winning wine and pamper yourself at The Villa, a luxury B&B. Spend your days exploring the local golfing, fishing, and skiing. Or recharge with a spa treatment and a glass of wine in front of the magnificent stone fireplace.

A weekend getaway, corporate retreat, family vacation, engagements, elopements, rehearsal dinners, or special events...it’s the perfect place to relax, re-inspire, and rejuvenate – both inside and out.

A longtime student of and adherent to mountain traditions, Jim Casada’s latest book, co-authored with fellow devotee to old-time ways, Tipper Pressley, is Celebrating Southern Appalachian Food: Recipes and Stories. It is due out in the next few months. To be notified when it appears or to sign up for Casada’s free monthly e-newsletter, contact him at jimcasada@ comporium.net.