6 minute read

Lieutenant Colonel John Collier – A Vet’s Story | By Steve York

Vietnam Veteran, John Collier

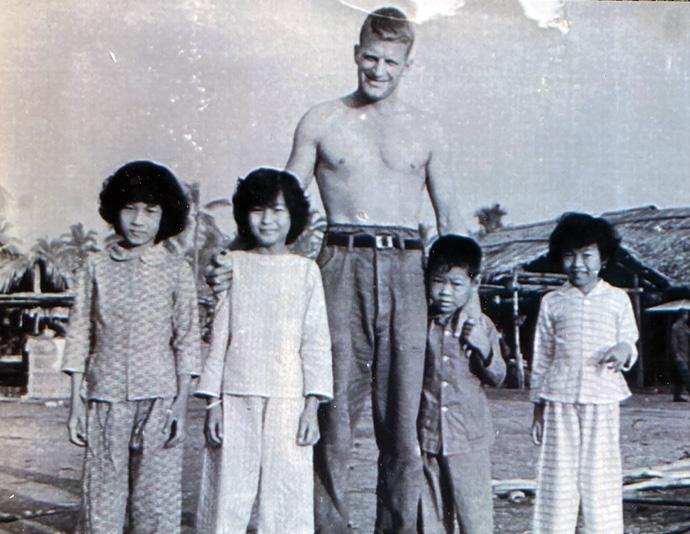

Collier with Vietnamese family Veterans Day: One Vietnam Vet’s Story

By Steve York

That was November 22, 1963. And that was Banner Elk’s own Retired Lieutenant Colonel John Collier. It was his first stint in Vietnam. But it wouldn’t be his last.

“It was a pretty depressing start for my Vietnam service and a shock for me and anyone serving over there in late 1963,” Collier added in his unmistakably native Massachusetts accent. No doubt the shared home state of Collier and President Kennedy may also have added a sharp sting to that already tragic news.

Kennedy had just increased the U.S. military commitment to that war in hopes of defeating the North Vietnamese and bringing an end to the conflict without excessive delay. So, to have a soldier’s Commander-in-Chief slain halfway around the world in the assumed sanctuary of the United States of America could not have been more unsettling for military forces in the process of amping up their combat role in Vietnam.

In hindsight, it doesn’t escape some note of tragic irony that Veterans Day falls on the eleventh day of the eleventh month of each year and that the fateful date of Kennedy’s assassination, November 22, was exactly eleven days following Veterans Day back in 1963.

This national holiday to honor U.S. veterans initially began in 1919 as Armistice Day to commemorate the end of World War I, which occurred on November 11, 1918. Following World War II and the Korean War, the United States 83rd Congress amended the Armistice Day Act of 1938 changing the word Armistice to Veterans. And, in 1954, Veterans Day officially became a national holiday to honor the military service of all U.S. veterans of all wars.

For Vietnam Vets like Collier, Veterans Day comes with its own unique scrapbook of memories, both heroic and tragic. Collier’s personal scrapbook of photos, books, newspaper articles, historic records and archived video references literally spills across the top of his kitchen table and fills nearby bookcases. And his life story, which set the course for his eventual service in Vietnam, is as fascinating as his Irish-rooted New England wit and story-telling charm.

John Francis Collier was born in Danvers, Massachusetts, in 1934 as the middle child in a family of five. Four years later his mother died at the young age of 29 and, soon after, his father found himself unable to care for the children. So, the five kids were forced to become wards of the Commonwealth.

In 1946, after being shuffled around nine different foster homes, Collier was reunited with his two younger brothers, Bob and George, when they came to live in the Boston neighborhood of Charlestown with a caring foster family named Flynn.

But growing up a poor foster kid in a tough neighborhood like Charlestown meant you had to learn how to fight and stand up for yourself. Collier joined the local Boys Club, took up boxing and, later, the Club’s swim team. It was his swimming skills that helped him become accepted at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine. And it was at Bowdoin that Collier entered the school’s Army ROTC program.

ROTC led Collier to the Army Basic Infantry Officers Course at Fort Benning, Georgia, following college graduation. From there, he rose up in ranks, gaining respect and recognition from his commanding officers and—as destiny would have it—found himself in Vietnam on that fateful day of November 22, 1963.

LTG John J. Tolson presents the Silver Star Medal to MAJ John F. Collier, April 2, 1970. Collier with daughter, Kristen

His first Vietnam deployment had him and his unit dropped off in the Ca Mau Delta, wading through rice paddies, navigating through war-ravaged jungles and staying with friendly local families at night. He used his Vietnamese language training to get to know and love the people and their children. “In many ways, despite the war, this was a wonderful experience, and these were wonderful people. I wouldn’t swap it for anything,” noted Collier. That stint earned him a Bronze star in 1964 as well as a rough bout with malaria and a trip back to the States.

In 1965, Collier completed training for the elite Special Forces Green Berets in Fort Bragg and found himself chosen to serve as an Army Special Forces Exchange Officer to the British 22nd Special Air Service Regiment. That year gave Collier a world of travel adventure that included exotic locales such as Libya and Yemen. A year later he was assigned to write top secret Special Forces plans for the 18th Airborne Corp and served as a favored senior aid for the late Army Lt. General Robert Howard York.

Despite his safety as a valued aid to York and, later, Lt. General John J. Tolson, Collier eventually requested a return to Vietnam where he rejoined combat forces commanded by General Melvin Zais. That decision found him serving under Lt. Col. Weldon “Black Jack” Honeycutt as S3 Operations Officer of the 3rd 187 Infantry Battalion of the 101st Airborne Division. And that fateful decision landed Collier in the midst of one of the bloodiest and most controversial battles of the Vietnam War.

Under Honeycutt, Collier was responsible for overseeing the perimeter at the infamous battle of Hill 937, a.k.a “Hamburger Hill.” Hamburger Hill, or Dong Ap Bia (the hill’s Vietnamese name), was a strategic spot overlooking the Ah Shua Valley near the border with Laos, a major military transport route for the North Vietnamese army (NVA).

From May 10 to May 20, 1969, U.S. forces fought under constant and brutal enemy assault. Securing and holding that hill was deemed essential at the time. Later it was widely criticized and condemned as a grave military misjudgment when, after American forces finally captured the hill, they soon abandoned it to re-occupation by the NVA.

There were 70 American soldiers lost—39 in Collier’s group—and a total of 370 wounded. Collier was one of the wounded. He suffered a shrapnel leg wound and, later, a severely broken leg. But his performance at Hamburger Hill won him both a Silver Star for Gallantry In Action and a Purple Heart for being wounded.

Many others also received honors for their service during that war; some in person, some only posthumously. And, although each year’s Veterans Day evokes a personal sense of pride in Collier for his own military service, it is also a day for quiet and humbled reflection.

“I’m very, very fortunate to have made it back from Vietnam, to have truly enjoyed my 20-year military career, and to have been blessed with a wonderful family and dear friends in this beautiful mountain community,” noted Collier.

Ever with a glint of Irish cheer in his eye, Collier maintains a youthful spirit and a passion for life. In fact, the only time that that glint might dim is when he talks about the many brave soldiers who didn’t receive the public recognition and honor that they deserved. “On Veterans Day, my thoughts naturally turn towards all the veterans who were unrecognized yet performed with extraordinary courage—especially those who didn’t come home, and their loved-ones. Their stories are also a part of my story,” Collier added.