13 minute read

Birding with Curtis Smalling

Ailanthus altissima (tree of heaven)

wood trees. “We want as many people to be engaged in this pest, looking for it,” says Swink. She shares some examples of recent efforts to reach the public: “Posters are in rest areas, and we have coasters that we’ve taken to breweries and vineyards that really focus on the fact that hops and grapes are two key hosts for the SLF and major threats to those commodities. We basically want this message spread as far and wide as possible.”

What should you do if you’re out exploring in the woods or gardening on your property and you spot a spotted lanternfly? Remember these three phrases: See It, Snap It, Report It. “Please take a photo and try to include a size reference such as a quarter or pen,” Swink requests. Then send your photos to badbug@ncagr.gov. When submitting a photo be sure to include the location of the sighting, the date, and your contact information.

If you have questions about this invader, contact the NC Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services at badbug@ncagr. gov or 1-800-206-9333. You can learn much more about the spotted lanternfly at www. ncagr.gov/SLF and https://gardening.ces. ncsu.edu/spotted-lanternfly-resource-page/. Here, you can also view an expansive gallery of images that will help you discern whether the insect you’re seeing is the bad bug or if it is a harmless look-alike. You’ll also find information on identifying its favorite food source, tree of heaven.

Tamara Randolph is a N.C. Certified Environmental Educator and Blue Ridge Naturalist. She is the founder of Carolina Explorers: Adventures in Nature, a monthly educational program offered through the Banner Elk Book Exchange. You can reach Tamara at tamara@ NCexplorers.com.

The State of Our Birds

By Curtis Smalling

Wild Turkey – Photo:Ryan O’Keven | Rose-breasted Grosbeak – Photo: Sandra Rothenberg.

One of the most frequently asked questions I get is, “How are our birds doing?” That is, of course, a complicated question, but one that does have some answers. Fortunately, many folks, agencies, and volunteers spend a lot of time counting birds and we know a great deal about some and a little less about others. It might be interesting to summarize some of the current State of NC’s Birds for you.

Most often, we tend to think of the birds we see during the breeding or nesting season as the species we can help the most through our management actions or how we maintain our habitats on which they depend. Fortunately, for a majority of our nesting species, we have some long running data sets that can help tell us how populations of most species are faring. These “Breeding Bird Surveys,” as they are known, have been conducted on established twenty-five-mile routes for almost sixty years in some cases. This is a national effort, and here in NC about 170 species have enough data to estimate their long term trends and their annual rates of decline or increase. Of these, about a fourth of species (23%) are considered stable (those are species whose annual trend numbers are less than one-half of one percent change per year), 43% are increasing, and 33% are declining.

As you might expect, the species that are doing the best tend to be those that like what we do to the environment as we build or fragment the forest, and include species like our biggest winner, Canada Goose. But some others you might notice as increasing include House Finch, Tree Swallow, and Wild Turkey. Some coastal species have done well, including Brown Pelican, White Ibis, Laughing Gull, and Osprey. Bald Eagles, Wood Storks, and Mississippi Kites are also improving.

A few of the stable species include some of our most common birds like Carolina Chickadee, Eastern Phoebe, and Downy Woodpecker. Some of our woodland birds, also in this more or less stable group, include Ovenbird, Ruffed Grouse, and Acadian Flycatcher.

For the declining species, the biggest losses have been some that we often hear about from folks voicing their concerns over their declines. Once common and now rare birds include Northern Bobwhite, Eastern Whip-poor-will, and Common Tern. Even some birds that are still fairly widespread and common are experiencing big declines, including Eastern Meadowlark, House Sparrow, and Wood Thrush. As a group, the declining species are found in all major habitats, suggesting that each has its own set of challenges that may be habitat related, but could also include other reasons, as well, like competition, climate change, or other factors.

The good news is that a large number of people and agencies are working hard to help these declining birds and to keep others stable. The US Fish and Wildlife Service, NC Wildlife Resources Commission, and Audubon and its partners have numerous projects and initiatives to help birds.

Visit nc.audubon.org for ways you can help and to learn more about bird conservation in North Carolina. You can make a difference for birds in your own yards and woods and fields. With your help, we can keep moving more and more species from declining to stable or increasing!

Curtis Smalling is a Boone resident and the Director of Conservation for Audubon North Carolina.

BIRDING

Mountain Living and the Importance of Local Information Outlets for Severe Weather

By Angela Hessenius, Joanna Parkman, Deanna Corin, and Montana Eck

Valle Crucis flooding / Photo by Jaybird Aerial Photography, www.jaybirdaerials.com

Whether you have been here all your life, or just enjoy visiting the mountains, you have likely experienced some sort of severe weather or natural hazard in the mountains of western North Carolina. Between the Horton Fire in 2016, Hurricane Florence in 2018, and an ice storm just months ago, mountain communities of the Old North State are well acquainted with a variety of natural hazards. The impacts of these events can affect the regional economy and pose significant risks to public health and safety. Moreover, these events are predicted to grow in frequency and intensity over the coming years due to a changing climate.

Native Appalachians and frequent visitors know how volatile the weather can be in these ancient hills, but it is not always clear where residents can turn for trusted information in moments of crisis or uncertainty. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted information challenges as communities have had to navigate conflicting information from various sources to keep themselves safe. As the number of potential sources continues to grow in this technological age, what makes an information source, such as social media or your local news station, a trustworthy place to turn to when getting information on severe weather events?

That’s one of the questions a group of researchers at Duke and UNC-Chapel Hill set out to investigate this year as part of an interdisciplinary Bass Connections (https://bassconnections.duke.edu/) research project focused on wildfires and public trust.* Initially, the team intended to conduct in-person interviews in Ashe and Watauga counties to hear firsthand accounts of unpredictable weather events in the information age, but public health concerns required an alternative approach for the research. Students created an online survey to ask questions within these communities about trust, risk perceptions, and where people get information in order to understand how individuals make choices when preparing for hazards or severe weather. Drawing from the insights and networks of local organizations, the team partnered with the New River Conservancy Citizen Science Program and North Carolina Cooperative Extension Centers in Watauga and Ashe Counties to connect with residents. With nearly 80 survey responses from Ashe, Watauga, and Rockingham Counties, we began to uncover some of the factors that influence trust and information-seeking in the High Country and the upper Piedmont region.

One of the key findings from these survey responses is that there is some discrepancy between the types of sources that people trust the most and the sources that people nonetheless use regularly. For example, the sources that were ranked as most trusted included local online weather sources (such as Ray’s Weather Center) as well as state officials, county health departments, and county emergency response agencies. When asked which sources people turned to the most often for information during a natural hazard or severe weather event, residents again ranked local online weather sources as the most frequently used source. However, the next most frequently used source was social media, which ranked last in terms of sources that survey respondents trusted generally. The next most often-used information sources were local news stations, local newspapers, and neighbors or family members. While there is still a lot to learn, one important reason for this mismatch could be that the sources that are most trusted are not the same as the sources that provide the most easily-accessed and widely available information. Trusted sources might not provide new information at the same rate as a person’s social media feed does.

From COVID-19 to natural hazards such as wildfires, communities in the southern Appalachian mountains—like communities across the country—will continue to face risks to public health and safety. One of the most important ways to prepare for and adapt to these uncertainties is to have trusted sources of information that people can rely on. During a hazard or disaster, access to accurate and trusted information can save lives.

We all face the challenges of navigating a world where information is everywhere, but we may not completely trust whether that information is accurate, reliable, or truthful. “Even though we are seemingly awash in information,” says Dr. Brian Southwell, co-director of the project at Duke, “people nonetheless sometimes struggle to make sense of information or to find relevant information to their specific needs.”

The collaborative Duke-UNC research project suggested some key takeaway messages for both consumers and communication professionals serving the High Country. Having a go-to source of trusted information during an extreme weather event can be a key part of disaster preparedness and resilience. Some residents in western North Carolina might not currently have a regular source of information about extreme weather and weather-related hazards that they rely on, so there are opportunities for future initiatives.

Government officials and news media can work to provide accessible information and build trust with constituencies, but importantly being a trusted source alone does not guarantee information access for residents. For example, research results showed that county and state governments are highly trusted but not as frequently turned to for information. This indicates an opportunity for improving channels of communication from these local levels to

communities, especially during an emergency. Local media sources may also consider building trust within their communities by seeking to further understand and respond to local needs.

Access to trusted information is an essential part of building resilient and adaptive communities, and our High Country communities are positioned to face this challenge directly. Whether it be heavier precipitation events, higher nighttime temperatures, or more variable winter weather, those who live and frequent the mountains of western North Carolina are already experiencing the impacts of a changing climate. With 2018 being the wettest year on record in NC and 2019 being the warmest, there have been an increasing number of hazards in the mountains, whether it be flooding or heavy rain causing unsafe road conditions, power outages, or property damage. Continued research is needed to further develop our understanding of the local communication strategies that aim to keep residents safe during these events. In the meantime, we believe that strengthening reliance on the already existing local assets and capitalizing on the importance of trust are key strategies to increase Western North Carolina residents’ safety and resilience during future extreme events.

*Note: The 2020-2021 Bass Connections team included Brian Southwell1,2,3, Shane Stansbury2, Deanna Corin3 , Montana Eck3, Angela Hessenius2, Joanna Parkman2 , Rebecca Sauer2, Yunfei (Leslie) Li2, Audrey Magnuson2 , Callie Turner2, Alana Baker4, Jason Snyder5, Mary Clare Hano6, Debbie Crane7, and Andrew Olson2 .

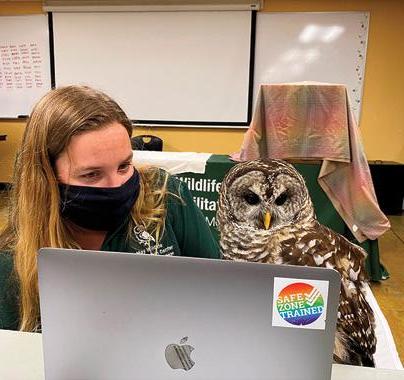

[1] RTI International [2] Duke University [3] University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill [4] Rockingham Community College [5] Appalachian State University [6] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [7] The Nature Conservancy Kara Bush and Sealy doing virtual program

Wildlife Ambassadors as Partners in Education

By Nina Fischesser, Director, May Wildlife Rehabilitation Center at Lees-McRae College

WILDLIFE REHABILITATION

In normal times hundreds of people come to see the wonderful wildlife who are presented at the May Wildlife Rehabilitation classroom. What most people don’t see is all the training and relationship development with the animals and their trainers. In rehabilitation, the goal is to stay detached so that the animal will stay wild in preparation for successful release back to the wild habitat from which he or she came. In education, the goal is to gain the trust of the animals so they are comfortable in teaching settings of all kinds.

Every spring semester the Lees-McRae College wildlife rehabilitation students are enrolled in a course called BIO 282: Wildlife as Partners in Education, in which they start the adventure of developing trust and working with two or three individual ambassadors (non-releasable animals who represent their species). Pairing a student with the right animal for them is a task that takes time. We employ a training technique called positive reinforcement, which is a concept in behavioral psychology that is used to help strengthen and teach desired behaviors. In the case of training wildlife, we use food as the reward stimulus. This method combined with gaining trust is the most effective method for us to train our animals.

What you might see at a presentation, for example, is our opossum ‘Opal’ using her keen sense of smell to find a grape or favorite food. Opossums have poor vision but incredible sense of smell to find food in the wild. She knows that being on the table in front of an audience means that she will seek out that treat food item. A hawk eats mice, so we might not use that as a demonstration in front of an audience, but we have used mice in training to teach them to step up on a glove, or to step back into their travel box prior to being in front of an audience.

Before a student actually holds an ambassador on a glove, they might just sit and read to the animal, getting them used to their voice and presence near them. The student would observe all the subtle training techniques a mentor uses with their ambassador that helps with each individual’s success. Some hawks don’t like going through doorways, some get nervous on a windy day, some are fearful of a ceiling fan in a room. Turtles and snakes must get used to the public touching them, so we handle them at every chance to help them get used to being touched by people at presentations. Touching is especially effective in teaching kids about reptiles, allowing them to feel their scaly skin or shell.

Ultimately, these wild ambassadors have a very important job. They inspire people to want to protect the very homes and ecosystems that these animals live in, and support the important work that we do to heal the ones who need a second chance.

Come learn more by attending free public presentations on Fridays and Saturdays at 1 p.m. at the Banner Elk Town Park Pavilion, Banner Elk, NC 28604. You can also contact us for off-site presentations (fee required). Call us at 828-898-2568. No dogs near wildlife presentations, please.