6 minute read

Wisdom and Ways with Jim Casada

WISDOM AND WAYS

The Hillbilly Highway

and the High Country

By Jim Casada

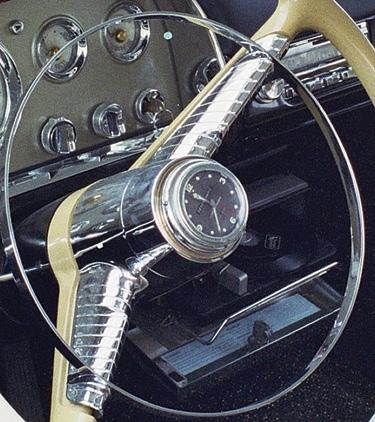

Phonograph in 1956 DeSoto

The origins of the description “Hillbilly Highway” are obscure, although they probably date back to the 1960s when the massive exodus of residents out of the impoverished regions of Appalachia which began in the aftermath of World War II peaked. At that point in time the term hillbilly was used in a derogatory fashion although today many natives of the Appalachian High Country, including this writer, wear it as a badge of honor. The highway those migrants were traveling in search of a better life was U.S. Route 23, and it carried them from their highland homeland to the industrial cities of the upper Midwest. Michigan locations such as Detroit, Pontiac, and Flint offered good paying jobs in automobile factories, while other industries in Cleveland, Chicago, Milwaukee, and Cincinnati also beckoned.

Poverty was rampant in the region from where the work-seeking refugees fled. The decades long timbering of the southern Appalachians had come and gone, leaving denuded slopes prone to erosion and far too steep for agriculture. Once pristine trout streams were fouled by silt and devoid of trout, while hard-working mountain folks could do little but figuratively shake their heads in dismay as available timber vanished, taking jobs with it. Worsening the impact of the inevitable bust which followed the logging boom was the deadly blight which wiped out the dominant tree of the Appalachian slopes, the American chestnut, in a period of only a few years. That disaster transpired at precisely the time of the Great Depression’s onset and the end of the great logging era and took with it the income available from cutting chestnuts for acid wood, marketing the nuts for vendors to roast and sell on city street corners, and what had seemed an inexhaustible source of material for fence rails, rough lumber, and other building purposes.

Once plentiful jobs became scarce as hen’s teeth and subsistence farming offered partial relief at best. Proud mountain folks, never scared of work and always willing to pull themselves up by their boot straps, found themselves in desperate straits. As a high school classmate (I graduated in 1960) of mine put it, and her description of family economic circumstances would have been applicable to many, “we were destitute.” The options for many were stark—stay in their beloved hills and constantly fight starvation or take the Hillbilly Highway to find work.

That’s why tens of thousands of folks from the country, small towns, and even the few cities scattered along the southern spine of the Appalachians took to the Hillbilly Highway. They desperately needed work, and soon neighbors and family members who had traveled U.S. Highway 23 ahead of them were sending back word of excellent pay and, in many instances, portions of that pay as well. They were transplanted in a physical sense, but almost without exception their hearts remained in the High Country. That was one of the more remarkable aspects of the whole work migration phenomenon and it speaks volumes about the strength of a sense of place in the hearts and minds of mountain people. Each year vacation time would find those economic transplants back in the mountains, and after twenty-five or thirty years of work led to retirement, they moved right back to the land of their roots.

Talented singer/songwriter Dwight Yoakam captures the poignant, gut-wrenching nature of the entire phenomenon in the lyrics of his powerful song which plays on the traditional three Rs of education. For him and his song title, the three Rs were “Readin’, Rightin’, Route 23.” As he suggests, coal-mining folks in his native Kentucky, just like loggers and farmers in the mountains of North Carolina and Tennessee, thought “roads to the north . . . would take them to the good life that they had never seen.” Sadly, what they didn’t realize was “that old highway could lead them to a world of misery.” In the course of a few telling lines Yoakam captures the pathos and trauma of the entire experience while likewise expressing the love of place which has always held highlanders in its thrall:

Have you ever seen ‘em

Put the kids in the car after work on a Friday night

Pull up in a holler about 2 a. m.

And see a light still shinin’ bright

Those mountain folks sat up that late

Just to hold those little grandkids

In their arms, in their arms

And I’m proud to say that I’ve been blessed

And touched by their sweet hillbilly charm.

Man selling roasted chestnuts Courtesy USDA Forest Service , Southern Research Station

That sort of weekend trip, while demanding, was possible from those hailing from the nearest fringes of Appalachia in Kentucky and West Virginia, but for those living farther southeast along Route 23 the distance was simply too great. They had to wait until vacation time, which often coincided with a family or church reunion or perhaps traditional summertime activities such as brush arbor revivals, week-long tent revivals, or all day singing with dinner on the grounds. Then those who had grown up in towns and the sprinkling of small cities along Route 23—Franklin, Sylva, Waynesville, Asheville, and Mars Hill in North Carolina and then on through Sam’s Gap into Tennessee and Flag Pond, Erwin, Unicoi, Kingsport, and Johnson City before crossing the state line and heading towards Gate City, Virginia—could return home for a blessed, soul soothing week or two in the embrace of their beloved mountains.

Along with Yoakam, Steve Earle wrote about this patchwork quilt of regional history in another song, this one bearing the title “Hillbilly Highway.” It is less specific in terms of focusing on lifestyles and economic necessity, but the recurrent refrain, “that old hillbilly highway goes on and on” is catchy and reflective of what was indeed the case for much of the latter half of the last century.

In recent decades things have changed, and in some cases dramatically. The locales where there were once enclaves of hillbillies working in factories while they dreamed of home have today become a region known as the “Rust Belt.” The Hillbilly Highway, formerly what was in essence a one-way avenue of asphalt leading from the mountains to Motor City and similar environs, at least when it came to economic opportunity, has seen a remarkable reverse in travel direction. Today all roads seem to lead to the High Country as folks who visit and drive along Highway 23, not to mention other routes from all compass points, increasingly realize why the High Country held the souls of mountain folks so firmly in its grasp. Those simple people, accustomed to living close to the earth and keenly aware of the fact that there was more to life than earning a livelihood, understood that their roots ran deep in the backside of heaven.

Today outlanders, increasingly appreciative of why there was such an entrenched love of place among those who had called the land of the Hillbilly Highway home for generations, are anxious to share this land of steep ridges, deep hollows, magic, and mystique. In a real sense that old Hillbilly Highway does indeed go on and on forever, but in the hearts of those who know and have long known it best, its final, fitting destination is where it began—in the Appalachian High Country.

Jim Casada is a full-time freelance writer and an appreciable portion of his work touches on his Appalachian roots, with his most recent book, A Smoky Mountain Boyhood: Memories, Musings, and More being an example. To learn more about his writings, order a signed copy of this book, or sign up for his free monthly e-newsletter, visit his website at www.jimcasadaoutdoors.com.