6 minute read

The Town that Wouldn’t Drown | By Edwin Ansel

Old Butler: The Town that Wouldn’t Drown

“Maaaaaatthew!”

A woman leans out the back door of a small wooden house.

“Naaaaaancy!”

She has short dark hair. She’s wearing an apron.

“Dinner!”

She looks out to the west, to the fields on the other side of the Watauga River. The sky is gray. The days have gotten so short.

About this time a big car, a Ford sedan, pauses at the curb out front. The wheels are caked with clay and the whole thing is gray from rock dust. A man climbs out and then turns back to the car and waves. He’s got a lunch pail in his left hand and a bundle of dusty work clothes tucked under his arm.

The children dash across the street to greet him. Nancy jumps into his arms. Matthew takes the lunch pail and runs to the door.

“Daddy’s home!”

The woman comes out and they stand together on the narrow porch.

“It’s done,” says the man. “All done.”

One last time. Settlers came to the bottomland that became Butler, Tennessee as early as 1769, the year Daniel Boone trekked through the area on his way to Kentucky. In about 1820, Ezekiel Smith built a grist mill near the confluence of the Watauga River and Roan Creek and a community grew around the mill. The turning point for this community came in 1902, when the Virginia & Southwestern Railroad arrived. The town was incorporated as Butler soon afterwards, in honor of Colonel Roderick R. Butler, who had served in the Union Army during the Civil War and who represented the people in that community in both the state and national governments.

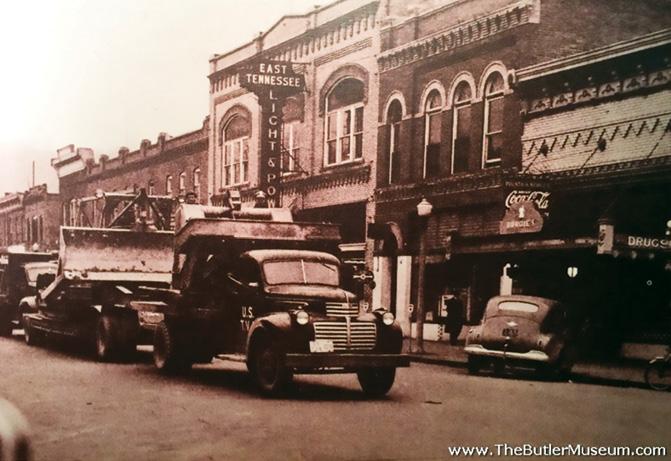

Over the next thirty years Butler grew and prospered. The railroad carried lumber and minerals away to market and came back with modern manufactured goods. Main Street was lined with shops housed in brick buildings. The Blue Bird Tea Room and bus station, across from Ritchie’s Hotel. The City Market. The Butler Confectionary, where the older kids gathered after school. Stout’s Barber Shop. The Central Service Station, repairing all makes and models. Ramsey’s Hotel. The Butler City Hall and the Jail, known affectionately as “the bughouse.”

The most impressive buildings were the churches. The Butler Methodist Church had gothic windows and a tall, pointed steeple. The Butler Christian Church was simple but well-proportioned, with a straight, three story bell tower. The Butler Baptist Church, which had been meeting since settlers first came to the valley, was simply large, having more than five hundred and fifty members.

Life in town was slow and peaceful in a way that today we sometimes dream about. Thelma Eggers Cutshall was a child in Butler, and this is how she looked back on her childhood. “I remember best of all the rest times when we sat on the porch and watched people go down the street … from the Depot … on their way to … the R. N. McClain Store. I also remember lying in the sunny spots in early spring or late fall. We had a cow and a barn to house her, two hogs to fatten for the winter’s meat, … Oh, yes, we had a garden which I hated because we had to take a tin can with a bit of kerosene to pick off the bean and potato bugs … Only memories remain of the first day of May, when we were allowed to shed our shoes … the feel of that grass to my bare feet. It seems I can still feel that excitement.”

R. N. McClain deserves a special mention. He ran a general store serving the families in Butler, but he knew that there were hundreds more up in the hills and hollows who could not make the trip to town to shop. To serve them, he created the Rolling Store. A Rolling Store was a truck that resembles a modern moving van and that was stocked with almost everything you might find in an old general store: groceries, hardware,

Watauga Lake today

By Edwin Ansel

cloth, kerosene, cane sugar, and so on. In other words, things folks needed but couldn’t grow or make for themselves, delivered to their door. Sound familiar? The trucks returned from the hills with eggs, butter, herbs, pelts, poults, just about anything the customers produced. “We Buy & Sell Everything” was McClain’s motto, and it said so right there on the driver’s door.

So, by 1940, Butler had grown into a small town, an ideal small town. But then came a perfect storm. It had been brewing from the very beginning. In 1902, the same year that brought the railroad, Butler suffered a flood. And again in 1916. And again in 1924. And finally, in 1940, a flood that washed away much of that railroad, and thus, much of the foundation for Butler’s prosperity. About the time that Butler was incorporated, the Watauga Power Company built the Wilbur Dam on the Watauga River to provide electricity to nearby Elizabethton, and in the 1920s other companies began exploring the potential for more and larger hydropower dams on the Watauga. Butler was also a victim of its own industriousness. Cutting timber for far away markets was unsustainable. By 1940 they’d pretty much run out of trees. People started leaving Butler, looking for greener pastures. And finally, there was the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). An agency with immense power. The flood of 1940 and the need for electricity for national security gave the agency just the rationale that it needed for a new dam. Butler was caught between the forces of nature, money and a bureaucracy. The Watauga Dam was authorized on December 17, 1941, just ten days after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

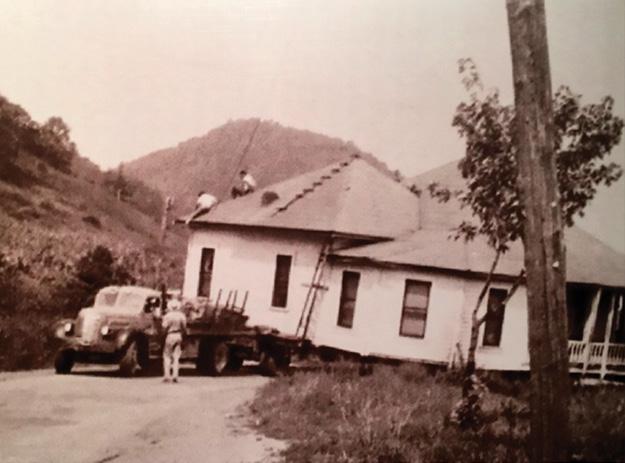

Soon, agents for the TVA began knocking on doors. People were told they’d have to move. Reactions were mixed. Matthew and Nancy’s parents saw the dam as an opportunity, and their father helped to build it. Many more were dead set against it. But threats and petitions changed nothing. A few farmhouses were moved to higher ground. But the brick storefronts and the handsome churches were lost.

But not all was lost.

The community—the fellowship of the people—was not lost. Some of the neighbors stayed close, formed a new town of Butler on the shore of the new lake. They’ve remained close to this day, celebrating, for example, “Old Butler Days,” a festival to honor their old stomping grounds. They have built and furnished a delightful museum filled with thousands of the simple items that illustrate those times, and more powerfully, hundreds and hundreds of photographs of those neighbors.

Something was even gained. Butler, called the “Town that Wouldn’t Drown,” is also this—The Town that is Forever Old. In 1948 the waters closed over it. That original town of Butler stopped growing and changing. It has been spared the tumult of the last sixty years. Living on in their memories, Old Butler remains what it was when last those neighbors last saw it, an idyllic home town in a quiet highland valley.

Photos courtesy of the Butler Museum. Note that the Museum is currently undergoing changes and may not be open during posted hours. Learn more about Old Butler and take a virtual tour of the museum through its expansive photo gallery at www.butlermuseumtn. com. For information on happenings and events taking place throughout the region, including Butler: www. johnsoncountytnchamber.org.