22 minute read

At the Crossroads: The Intersection of Transportation and Public Health

Michelle Nance / Emily Scott-Cruz

MICHELLE NANCE is regional planning director at Centralina Regional Council, providing planning services in the Charlotte region connecting land use, transportation, public health and economic development. Michelle holds a MPA and BS in urban and regional planning from East Carolina University. Honored as one of the 50 Most Influential Women in the Charlotte region, she was named 2017 Woman of the Year by the Mecklenburg Times and received the 2022 Planning Distinguished Alumni Award from ECU.

Advertisement

EMILY SCOTT-CRUZ is a transportation planner II with AECOM, based in Charlotte. She obtained her Masters in public administration from UNCCharlotte in 2019 after receiving her BA in Women’s Studies from Salem College. Prior to working for AECOM in February 2022, Emily worked as a Regional Transportation Planner with the French Broad River MPO in Asheville, NC, where she oversaw Section 5310 and JARC competitive grant processes, coordinated with transit agencies, and managed special studies including the Regional Transit Feasibility Study. Ever since her internship with Centralina Council of Governments while she was in grad school, Emily has been fiercely passionate about public transit and its potential to create more equitable cities.

ABSTRACT

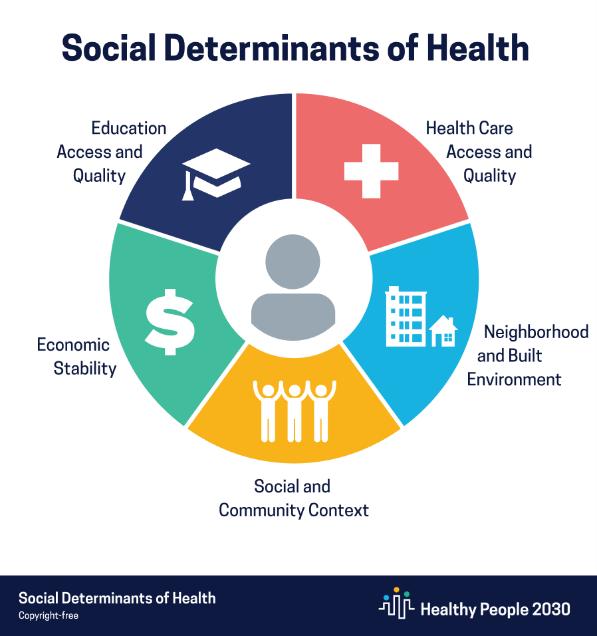

Inequities in public health exist throughout the world, stemming partially from disparities that arise in the social determinants of health (SDOH), or conditions where people live, learn, work, and play that affect risks and health outcomes. The five SDOH include economic stability, education access and quality, health care access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context (U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services, 2021). One thread that connects all the SDOH is transportation. Transportation influences mobility, impacting access to jobs, education, healthcare, and recreation while also impacting one’s physical surroundings. Thus, transportation policy, planning, and projects directly affect public health outcomes. This paper identifies ways that public health intersects with transportation planning and provides recommendations to North Carolina transportation planners, policymakers, and advocates for how to improve health outcomes through changing transportation planning practices, policymaking and prioritization.

Figure 1: Social Determinants of Health (Healthy People 2030)

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted inequities already present in public health. Health disparity or inequity, used interchangeably for this paper, implies a facet of health that can be shaped by policy and affects historically disadvantaged social groups systemically (Braveman, 2006). Inequitable health outcomes predated the COVID-19 pandemic, which can be observed in multiple ways, including the high rate of childhood obesity among Hispanic children, higher rates of infant mortality among indigenous people (NCHS, 2016; HHS, 2021) and greater likelihood of premature death from heart disease among African Americans (HHS, 2021). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported on the SDOH in connection to the risk of COVID-19 exposure and disparities in hospitalizations among racial and ethnic minority groups, showing higher rates of infection in areas with more disparities. (Cordes & Castro, 2020; Karaye & Horney, 2020). Additionally, counties with a travel time of over 20 minutes to a COVID-19 testing site had higher percentages of the population that were from racial and ethnic minority groups, uninsured and more rural (Rader, Astley, Therese, et al., 2020). The disparate effects that COVID-19 has on disadvantaged populations within the United States highlights the need to plan with equity at the forefront, especially considering that impacts of the pandemic are ongoing and that these inequities will continue to exist, and potentially increase, without action.

Transportation is a critical factor in the addressing health inequities and promoting positive change. Improving mobility increases access and positively impacts economic mobility and transportation choice, or the

provision of multimodal options, are central to achieving these results. This paper provides background on disparate effects that transportation has on health outcomes and offers recommendations to change traditional approaches to transportation planning practices to reduce health disparities and center equity.

HEALTH AND TRANSPORTATION

Health is a product of social, economic, and environmental conditions in which people live, work, play, and travel. As such, transportation produces direct impacts on individual health outcomes, as it affects mobility and access to services (American Public Health Association, 2010). One’s ability to access employment, food, medical services, recreation, and education affects physical, emotional, and mental health and overall quality of life. Not everyone has the same access to transportation. Where you live affects how you travel and how you travel affects other facets of your life.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), equity is the “absence of unfair, avoidable or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically, or geographically or by other dimensions of inequality,” such as sex, gender, ethnicity, disability, or sexual orientation (WHO, n.d.). This differentiates it from equality, which gives equal opportunity without recognizing that everyone comes from different circumstances which alter what is needed to reach a fair outcome. Equity entails resource distribution based on demand, and transportation provides means to connect resources across communities and improve the ability to meet demands. Historically, planning has reinforced policies and practices benefitting dominant social groups at the expense of disadvantaged groups, resulting in reduced access and increased mobility barriers for some communities (e.g. failure to invest in transit and pedestrian infrastructure in lower income neighborhoods and highway construction or locally unwanted land uses within black and brown communities). Lack of access to transportation correlates to poverty and race and the resulting impacts on health. Communities with limited transportation access experience poorer health outcomes, higher rates of pedestrian mortality, and greater unemployment (Smart Growth America, 2019). Changing transportation access and availability can change health inequities.

Multimodal transportation planning considers diverse transportation options, including walking, biking, utilizing public transit and driving automobiles and accounts for land use factors that affect accessibility. In practice, connected, multimodal transportation systems support and are supported by higher density, mixed-use development. These elements, along with policies for equity and inclusion, create communities of value, desired destinations for employers and residents, and opportunities for prosperity. Multimodal transportation contributes to positive health outcomes by encouraging activity, facilitating access to employment, healthcare, education, and recreation, and creating a safe built environment.

BUILT ENVIRONMENT AND SINGLE OCCUPANCY VEHICLES (SOV)

One of the SDOH is “neighborhood and built environment.” Systemic inequity has been reinforced through land use development and transportation planning practices over the years. Suburban zoning standards impact community growth patterns by separating land uses and increasing reliance on single occupancy vehicles (SOVs). Simultaneously, SOVs have dictated the development of transportation and infrastructure in the United States, leading to a focus on travel speed at the expense of access, connectivity, and community. Additionally, funding structures favor highway development. Fiscal Year 2020 NCDOT funding allocations totaled almost $5 billion in resources with over 77% allocated to highway construction and maintenance and only 6.2% assigned to other modes including public transit, rail, bicycle/ pedestrian, aviation, and ferries (NCDOT, 2020). Public perception tends to be that additional streets and road widenings relieve congestion; however, the fundamental law of roadway congestion is that new roads create new drivers, resulting in increased traffic, known as induced demand (Mann, 2014).

Our land use patterns have responded to the transportation infrastructure investments, focused primarily on the SOV. This emphasis on car infrastructure means that most individuals need a vehicle for daily access. However, car ownership is neither costeffective nor feasible for many, which creates obstacles adversely affecting public health. Housing and transportation are the two highest expenses for the average household. The cost of housing in growing urbanized areas threatens the prosperity of disenfranchised individuals by pushing residents further away from necessities and opportunities, limiting economic mobility and creating longer commutes. This tradeoff imposes steeper transportation costs in terms of car ownership and maintenance, insurance, and gas, a regressive tax that subsidizes highway improvements (Leinberger, 2009). This cycle of reliance on car ownership encourages physical inactivity, which impacts physical and mental health, sustains inequities, contributes to traffic related deaths, and increases exposure to pollution.

Furthermore, transportation planning has cemented inequities within cities. Inner city highways serve as physical boundaries separating communities by socioeconomic status and race. Highways have increased urban sprawl, resulting in white flight from city centers to suburbs, spatial mismatch, and environmental injustice related to construction and emission pollution that accompanied projects in low-income, minority neighborhoods (Bullard & Johnson, 1997; Sanchez, Stolz, & Ma, 2003). While roadway development pushes marginalized groups away, multimodal transportation such as pedestrian and cycling infrastructure and public transit improves accessibility through mobility, especially as growth in North Carolina continues to displace lower income individuals.

ENVIRONMENTAL CHALLENGES

Health problems are most pronounced near heavy traffic (Iroz-Elardo, et al. 2014). According to the WHO (2018), only one in ten people were able to breathe clean air globally in 2014. Air toxins and airborne particulates impact internal organs, causing respiratory

illness, cardiovascular problems, cancer, and premature death. Designing infrastructure that exclusively caters to SOVs increases congestion, commute times, and costs while neglecting vulnerable populations (Bartle & Devan, 2006; Roseland, 2012).

After nearly two years of a global pandemic that affects the respiratory system, the importance of clean air and environmental justice is further highlighted. As of June 2020, the CDC reported that 21.8% of COVID-19 cases in the United States were African Americans and 33.8% were LatinX, despite the fact that these groups comprise only 13 and 18% of the US population, respectively (Don Bambino et al, 2021). Communities impacted by underlying health conditions have been adversely impacted by COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths, exacerbating health disparities. These underlying health conditions have root causes linked to lack of mobility and lower access to healthcare, healthy foods, and opportunities for physical activity.

SEDENTARY BEHAVIOR

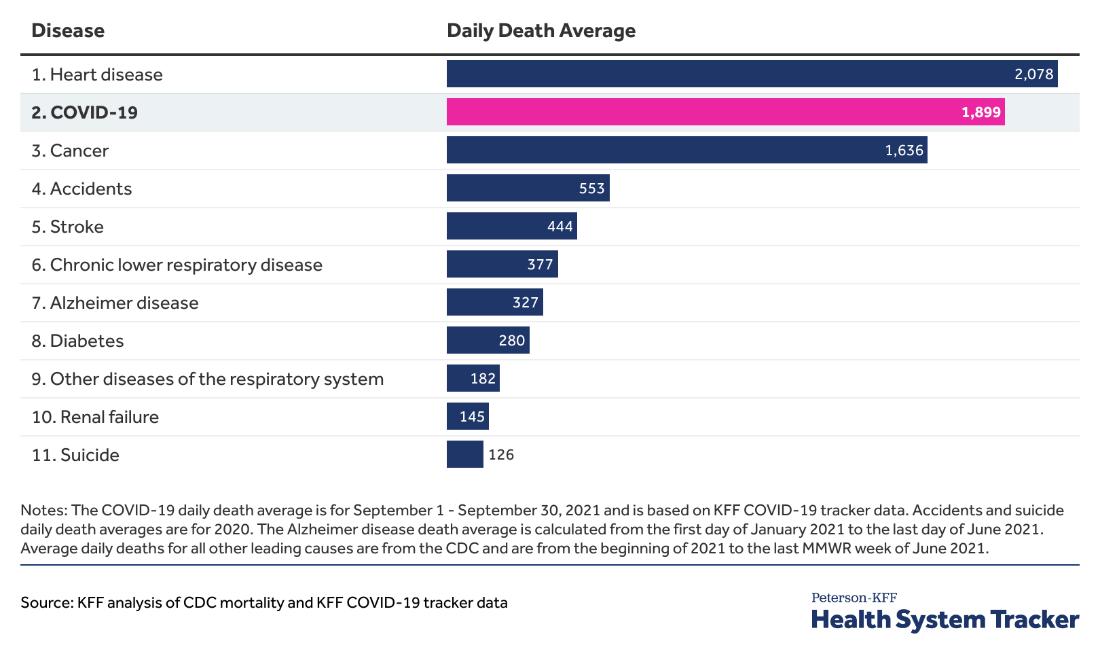

In addition to the environmental challenges that affect health outcomes and relate to emissions, construction, and congestion, sedentary behavior is a persistent problem. SOV travel patterns incorporate inactivity into normal life. Before COVID-19, there was a trend toward chronic illness as the leading cause of death. The chronic illnesses that soared to the top of the charts in leading cause of death are also influenced by lifestyle (heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, and accidents). Encouraging multimodal transportation to dissuade North Carolinians from persistent sedentary behavior connected to SOV use presents an opportunity to change health outcomes statewide.

Figure 2: September 2021 average daily deaths from COVID-19 in the US. (Ortaliza et al., 2021).

MENTAL HEALTH

More time spent in a car creates stress, adverse health impacts, and generally less time for the activities that make us content. A study conducted in 2011 determined that longer commute times increased family stress, correlating a 40% greater likelihood of divorce with commute times over 45 minutes long (Sandow, 2014). Another study revealed a correlation between commute times and increased blood pressure, heart rate, and lower frustration tolerance among students (Frumkin, Frank, & Jackson, 2004). Additionally, commuting patterns form the most predictive measure in determining civic engagement according to Robert Putnam (2000). Designing infrastructure that exclusively caters to SOVs continues to increase congestion, commute times, and costs while neglecting vulnerable populations (Bartle & Devan, 2006; Roseland, 2012).

Figure 3: Mortality rate of pedestrian injuries per 100,000 census population from WISQARS and Hospitalization rate per 100,000 census population estimated from HCUP-NIS, 2009–2016 (Hamann et al., 2020).

SAFETY CHALLENGES

In addition to physical health, mental health, and environmental problems caused by single occupancy vehicles, physical safety for all road users, regardless of mode, is threatened by current transportation practices. More than 38,000 people die every year in crashes on US roadways and pedestrian fatalities have increased dramatically over the last 50 years, making up 17% of all traffic deaths. According to a study done by the University of Iowa, mortality rates are higher among multiracial pedestrians, and Black and Multiracial pedestrians were hospitalized at a higher rate than white pedestrians.

While transportation has been a topic of discussion in connection to the social determinants of health, traffic safety and access to transportation has been less directly highlighted and have earned a place in the discussion.

EQUITY AND THE ROLE OF PLANNING

In an equitable community, everyone has access to recreation, healthy food, services, medical care, education, and shops regardless of race, class, age, gender, and religion. However, land use development and transportation have created geographic poverty lines. Access to public transportation has been shown to positively affect a community’s public health and economic vitality. Transit users are more active because public transportation riders start as pedestrians. Public transportation connected networks encourage multimodal travel and support community development patterns and investments that influence walking and biking. Public transit also reduces the transportation/housing cost burden, saving riders money on transportation (car payment, insurance, maintenance, fuel, parking, etc.) and simultaneously reducing commute stress, which is especially important for historically disadvantaged groups. Considering these benefits, a change in funding and investment in public transportation is an important course of action for North Carolina.

Making upstream, systemic change is challenging and requires creativity to incentivize transportation alternatives. This shift will require changing how we prioritize and fund transportation infrastructure— revising allocation of transportation resources; building strong local leadership and a movement supported by thoughtful messaging and a narrative to increase understanding of the issues surrounding transportation and public health, the impacts of our historic and future decisions, and the urgency of this worked based on population growth; following tested best practices that support a variety of implementation tools and community design principles conducive to transportation alternatives that prioritize equity; and tracking progress through data.

HOW CAN TRANSPORTATION IMPROVE INDIVIDUAL AND COMMUNITY HEALTH?

Transportation projects in NC are funded through a data-driven process known as Strategic Prioritization Investments (STI), which allows NCDOT to develop the State Transportation Improvement Plan (STIP), a 10-year funding plan for successful projects in three tiers—Statewide Mobility, Regional

Impact, and Division Needs. This process involves rounds of scoring roadway, public transportation, bicycle, pedestrian, rail, and aviation projects on specific criteria. Funding is distributed based on a prescribed modal split—90% highway, 4% non-highway, and 6% competitive (N.C. Gen. Stat. § 136189.11). While STI creates a non-political, quantitative mechanism for funding projects in a way distributed amongst different tiers (Statewide Mobility, Regional Impact, and Division Needs), its specifications could be improved to enhance support of multimodal options. The Nashville Area Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) incorporated health impact assessments (HIAs) into their transportation project scoring. By utilizing HIAs, the scoring process considers potentially significant direct, indirect, and cumulative health impacts that proposed projects could have on disadvantaged populations by including an analysis of baseline health and determinants of health in affected populations (Bhatia, 2011). In 2010, the MPO adopted a 2035 Regional Transportation Plan shifting the focus towards active transportation projects. Of the 100 points that the MPO could award to roadway projects, 60 points involved considering air quality, bike/pedestrian, safety, health, and equity. Using these criteria for prioritization, 70% of projects in the updated plan included active transportation infrastructure compared to 2% of projects in the 2030 plan developed in 2005 (Raynault & Christopher, 2013).

In addition to a new scoring methodology, the MPO conducted the Middle Tennessee Transportation and Health Study, a regional study linking health and transportation followed by the implementation of the Integrated Transport and Health Impact model predicting and monetizing populationlevel health impacts associated with shifting projects towards active transportation modes (Meehan & Whitfield, 2017). As a result of Nashville’s commitment to public health, there has been a 57% increase in sidewalks, an increase in Complete Street designs, and a decrease in workers driving alone to work (Meehan & Whitfield, 2017). Nashville shows the importance and impact of prioritizing health in transportation planning. By changing the scoring practice of SPOT, Nashville changed the way that funding would be allocated.

OPPORTUNITIES

• Expand criteria for prioritizing transportation projects. Currently resiliency and health impacts can’t easily be considered in scoring without changing STI law. Making STI law more flexible would allow funding to be adaptable to constantly changing needs. • In North Carolina, there are taxation opportunities that are not utilized fully. Currently, a limited number of

North Carolina counties impose a sales tax designated for transportation improvements, which could be used in the other counties to provide funding for multimodal transportation development. • A change in the dedication of funding for road projects to projects that encourage a mixture of modes (Complete Streets) offers the chance to increase funding for more connected transportation, improving health outcomes. Complete

Streets are designed and operated to enable safe access for all users of all ages and abilities, with a goal of making it easy to cross the street, walk to shops, bike to work, allow buses to run on time and safe for people to walk to and from train stations.

North Carolina’s fast-growing urban areas have different needs than its expansive rural areas and provide an opportunity to test new areas of policy and infrastructure. The importance of efficient transportation in these urban areas cannot be overemphasized and is directly tied to the state’s overall economy and ability to move goods, products and people. Multimodal transportation choices are critical to provide alternative methods for transport. In 2017, North Carolina’s transit systems provided over 70 million trips and transit needs will only increase with population growth and generational preferences, especially in urban areas. A focus on multimodal transportation will require shifts in mindset, policy, and funding across society, from the general public, to local and state elected leadership.

As such, positive messaging around public transit should be developed to appeal to audiences with different values. If public transit is seen as a community service critical to supporting a complete system, it stands to gain value and will receive funding. Transit can serve as the backbone to both urban and rural communities and lay a foundation where employment, residential life, and retail can prosper, where economic development can occur, and where new infrastructure investments can be targeted.

OPPORTUNITIES:

• Develop core supportive messaging and an ongoing campaign to educate officials, business leaders, community leaders, and public servants about the benefits of alternative transportation options and the opportunities lost with inaction.

• Emphasize the benefits of multimodal transportation over the continued emphasis on infrastructure designed for single occupancy vehicles. Include conversations about improving safety, improving air quality, and decreasing the cost burden of transportation. • Create a campaign including educational forums for stakeholders along with city/ county managers, planners, engineers, and transit officials to building a strong base of understanding and support.

Goal: Local and Regional Policy Implementation Supporting Multimodal Transportation

Traditional transportation planning supports car-centered design and development, undervaluing multimodal means of transportation. Certain policies already encourage a mixture of transportation modes, like the NCDOT’s Complete Streets Policy. In North Carolina, the Complete Streets Act of 2009 (S.B. 584; H.R. 1443) was adopted in recognition of the significant influence that street design has on safety, environmental integrity, public health, economic vitality, and community livability. Despite the existence of a state policy, local governments often lack the resources to plan networks of safe streets or to rebuild their streets (National Complete Streets Coalition, 2015).

OPPORTUNITIES:

• Support the development of a personcentered mobility application that connects users to multiple mobility options. This requires consistent, shared data across jurisdictions and private/public entities including public transportation, micro-mobility, and local governments. • Develop model local ordinance language for Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) across a variety of community sizes across the urban/rural spectrum. ▷ Educate local government leaders and staff on TOD policy. ▷ Provide technical assistance teams to communities to assist with selecting a policy for their community based on long-range goals. ▷ Provide local technical assistance to incorporate planning goals into code, seek willing developers, review development proposals, understand financing mixed use, and offer development incentives. • Provide training and assistance on incorporating Complete Streets policies locally and revising street standards. • Support the development of safe and well-connected bicycle and pedestrian networks through local planning. • Develop checklists for efficient siting of community facilities and destinations, e.g. social service facilities, parks and recreation, child care and others that are frequented by historically disadvantaged groups, to push these investments into areas with existing/future transit access. • Provide training and assistance on updating parking codes to reduce subsidies for automobile use. • Encourage policies that support commutes by transit, walking, biking, etc., such as paying for transit rides, providing showering facilities, providing flex time for exercise, or participating in regional transportation demand management programs.

Tracking progress is critical for determining efficacy and for appropriate evaluation of change. Currently, there is no statewide indicator that can be used to track transit use over time. Considering the direct and indirect impacts that transportation has on public health, transit indicators should be added to the Healthy NC 2030 Plan and the NCDOT’s NC Moves 2050 Plan as these plans are updated.

OPPORTUNITIES:

• Convene a thought leader group to develop a framework for tracking/ measuring progress towards multimodal transportation. • Identify how the results of improved tracking will be delivered, the frequency of reporting, and the audiences who will have access. Audiences should include state elected leaders, business leaders, local government employees, transit operators, etc. • Support the creation of reports and publication of annual data, on various levels to identify agencies and data necessary to track progress.

CONCLUSION

According to the AICP Code of Ethics, “We shall seek social justice by working to expand choice and opportunity for all persons, recognizing a special responsibility to plan for the needs of the disadvantaged and to promote racial and economic integration. We shall urge the alteration of policies, institutions, and decisions that oppose such needs.” By presenting research and evidence regarding the connection between public health and transportation, discussing opportunities within transportation planning to address persistently disparate health outcomes connected to transportation, and recommending actions to make meaningful change, this paper aligns with core tenants of the AICP Code of Ethics. Ultimately, this is just a beginning. For meaningful change to happen, ideas and recommendations must be accompanied by action. NC leaders, transportation, transit, and land use planners must take proactive action in order to ensure that policies and actions don’t continue to adversely impact lower income individuals and minorities. In the past, development and planning has been guided by those who can afford to participate and influence. Having reached a point of our history that recognizes the institutionalized inequities of days past, planners must promote equity in every aspect of their jobs.

REFERENCES

AICP Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct. 2005.

American Institute of Certified Planners. Retrieved

Nov. 7, 2021, from https://www.planning.org/ethics/ ethicscode/. American Public Health Association. 2010. The Hidden

Health Costs of Transportation. https://www.apha. org/~/media/files/pdf/factsheets/hidden_health_ costs_transportation.ashx Bartle, J., & Devan, J. 2006. Sustainable Highways.

Public Works Management and Policy, 225-234. Bhatia, R. 2011. Health Impact Assessment: A Guide for

Practice. Accessed 11/16/21. Retrieved from: https:// humanimpact.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/HIA-

Guide-for-Practice.pdf. Braveman, Paula. 2006. “Health Disparities and Health

Equity: Concepts and Measurement.” Annual

Review of Public Health 27: 167-194. https://doi. org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102103. Bullard, R.D. & Johnson, G.S. 1997. Just Transportation:

Dismantling race and class barriers to mobility.

Gabriola Island, BC, Canada: New Society Publishers. Complete Streets Act of 2009, S.B. 584, 111th Congress. (2009). Complete Streets Act of 2009, H.R. 1443, 111th

Congress. (2009). Cordes J. & Castro, M.C. 2020. Spatial Analysis of

COVID-19 Clusters and Contextual Factors in New

York City. Spatial and Spatiotemporal Epidemiology, 34: 100355. https://dx.doi.org/10/1016%2Fj. sste.2020.100355.

Don Bambino Geno Tai, Aditya Shah, Chyke A

Doubeni, Irene G Sia, Mark L Wieland, The

Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 on Racial and Ethnic Minorities in the United States, Clinical

Infectious Diseases, Volume 72, Issue 4, 15 February 2021, Pages 703–706, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ ciaa815.

Frumkin, H., Frank, L., & Jackson, R. 2004. Urban

Sprawl and Public Health: Designing, planning, and building for healthy communities. Washington, D.C.:

Island Press.

Hamann, C., Peek-Asa, C. & Butcher, B. 2020.

Racial disparities in pedestrian-related injury hospitalizations in the United States. BMC Public

Health 20, 1459. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-02009513-8.

Healthy People 2030, U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and

Health Promotion. Retrieved 11/11/21, from https:// health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/ social-determinants-health HHS. 2021. Heart disease

and African Americans. https://minorityhealth. hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=19 HHS. 2021. Infant Mortality and American Indians/Alaska

Natives. http: //minorityhealth .hhs.gov/omh/content .aspx?ID=6907&lvl =3&lvlID=8. Iroz-Elardo, N., Hamberg, A., Main, E., Haggerty, B.,

Early-Alberts, J., & Cude, C. 2014. Climate Smart

Strategy: Health Impact Assessment. Portland

Oregon: Oregon Health Authority. Karaye, I.M. & Horney, J.A. 2020. The Impact of Social

Vulnerability on COVID-19 in the U.S.: An Analysis of

Spatially Varying Relationships. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 59(3): 217-325. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.006. Leinberger, C. 2009. The Option of Urbanism: Investing in a new American Drea. Washington, D.C.: Island

Press.

Lutz, C. & Lutz Fernandez, A. 2010. Carjacked: The culture of the automobile and its effect on our lives.

New York: Palgrave MacMillan. Mann, A. 2014. “What’s up with that: Building bigger roads actually makes traffic worse.” Wired.com, June 17. https://www.wired.com/2014/06/wuwt-trafficinduced-demand/. Meehan, L., & Whitfield, G. 2017. Integrating Health and

Transportation in Nashville, Tennessee, USA: From

Policy to Projects. Journal of Transport and Health, 4, 325-333. National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). 2016.

Health, United States, 2015: With Special Feature on

Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. Hyattesville,

MD. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus15.pdf National Complete Streets Coalition. 2015. Safer

Streets, Stronger Economies: Complete Streets project outcomes from across the country. https:// smartgrowthamerica.org/app/uploads/2016/08/ safer-streets-stronger-economies.pdf NCDOT. 2020. “Uses of 2020-21 NCDOT

Appropriations.” https://www.ncdot.gov/ about-us/how-we-operate/finance-budget/

Documents/2020-ncdot-funding-distribution.pdf NC Gen. Stat. Chapter 136 Article 14B § 136-189.11. 2013. https://www.ncleg.net/EnactedLegislation/Statutes/

PDF/ByArticle/Chapter_136/Article_14B.pdf Ortaliza, J., Orgera, K., Amin, K., & Cox, C. 2021.

“COVID-19 continues to be a leading cause of death in the U.S. in September 2021.” https://www. healthsystemtracker.org/brief/covid19-and-otherleading-causes-of-death-in-the-us/. Pucher, J., & Dijkstra, L. 2003. Promoting Safe Walking and Cycling to Improve Public Health: Lessons from

The Netherlands and Germany. American Journal of

Public Health, 93(9), 1509-1516. Putnam, R.D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The collapse and revival of American Community. New York: Simon &

Schuster.

Rader B, Astley CM, Therese K, et al. Geographic

Access to United States SARS-CoV-2 Testing Sites

Highlights Healthcare Disparities and May Bias

Transmission. Journal of Travel Medicine. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taaa076external icon Raynault, E. & Christopher, E. 2013. “Public Roads--

How does transportation affect public health?”.

FHWA, HRT 13 (4), May/June. Retrieved from: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/ publicroads/13mayjune/06.cfm Roseland, Mark. 2012. Toward sustainable communities: Solutions for citizens and their governments. New Society Publishers. Sanchez, T.W. , R. Stolz , and J.S. Ma. 2003. Moving to equity: Addressing inequitable effects of transportation policies on minorities (A joint report of the Civil Rights Project at Harvard University and the Center for Community Change). Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University. Sandow, E. 2014. Til Work Do Us Part: The Social Fallacy of Long Distance Commuting. Urban Studies, 51 (3), 526-543.

Siegel, C. 2010. Unplanning: Livable cities and political choices. Berkeley, CA: The Preservation Institute. Smart Growth America. 2019. The State of

Transportation and Health Equity. https:// smartgrowthamerica.org/wp-content/ uploads/2019/12/The-State-of-Transportation-and-

Health-Equity_FINAL-PUBLIC.pdf Speck, J. 2013. Walkable City: How downtown can save

America, one step at a time. New York: North Point

Press.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 2009. Healthy People 2030. Retrieved Nov. 11, 2021. 4. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-anddata/social-determinants-health. WHO. N.d. “Health Equity–Global.” Accessed

November 15, 2021. https://www.who.int/healthtopics/health-equity#tab=tab_1. WHO. 2018. Constitution of WHO: Principles. Retrieved from World Health Organization: https://www.who. int/about/mission/en.