7 minute read

The Nuances of Xiao Zhi:

Modern Insights of Laozi and Zhuangzi - Perspective is Self-Awareness, Attitude is Freedom

QÍWÙ (斉物) – A BEACON OF ULTIMATE LIBERATION & AUTHENTIC EXISTENCE

Embracing our true selves unlocks the hidden beauty in everyday life, revealing the very essence of existence aligns with Dao. In such a state, Laozi asserts that we are no longer susceptible to temptation of selfishness (wú hé huàn - 吾有何患), as expressed in Passage 13 of the Tao Te Ching.

Zhuangzi's second chapter, Qíwù lùn (齊物論), explores the transcendence of self-centeredness. He argues that fixating on self-righteousness, and self-importance (zì yǐ wéi shì - 自以 为是) limit personal growth, damage relationship, and impede our wellbeing. The four pillars of Qíwù (齊物) aims to overcome the ego self (Wǒ - 我) and works to reconnect us to the true self (Wú - 吾).

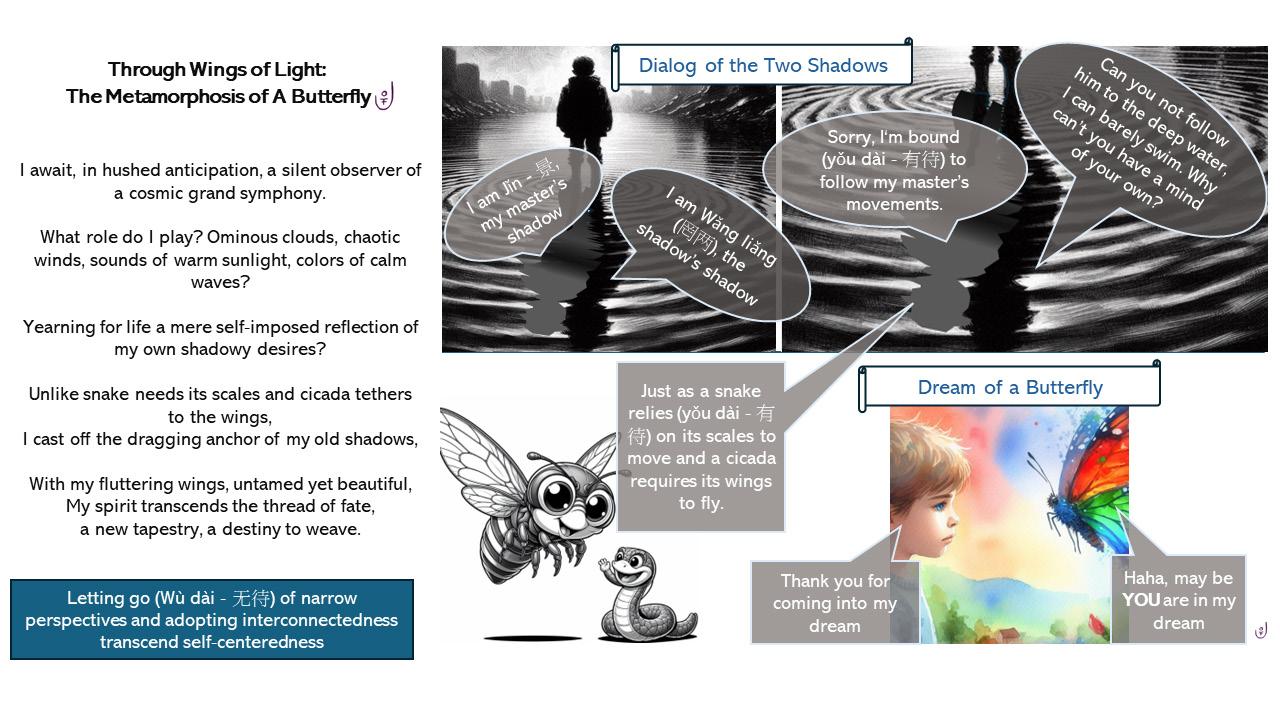

Zhuangzi concludes the chapter with a captivating dream of him becoming a butterfly (Zhuāng Zhōu

mèng dié - 莊周夢蝶). While the tale of the two shadows delineates the interconnectedness (yǒu dài - 有待) of the two selves, the adoption of new attitudes help blur the lines between them. The transcendence of selfcenteredness occurs through letting go of narrow perspectives and adopting interconnectedness emphasized in the concept of Qíwù (斉物). This liberation (Wù dài - 无待 ), like Zhuangzi’s transformation into a butterfly, represents the ultimate freedom of the true self, unburdened by the constraints of egotism.

TRANSCENDENCE OF SELF-

CENTEREDNESS

The chapter begins with a vivid picture of "wú sàng wǒ” ( 吾丧我 ), describing a character grappling with a loss of self. It then explores the sluggish demeanors of a Xiǎo zhī” (小知). Finally, Zhuangzi concludes with the captivating dream of him transforming into a

butterfly, symbolizing the liberation of the true self (consciousness). (Zhuāng Zhōu mèng dié - 莊周夢蝶).

THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN “WÚ吾” AND “WǑ - 我”

The Opening Scene – The teacher rested against the desk; eyes fixated towards the heavens. A student queries, "What's happening? Your body appears lifeless, but is your mind also in a void?" The teacher responded, "An insightful question! Today, I've achieved a state of self-forgetfulness (“wú sàng wǒ - 吾丧我”).”

In Chinese language two and a half millennia ago, “Wú - 吾 ” and “Wǒ我” denote distinct states of ‘self’ with significant semantic disparities. "Wǒ" refers to the tangible self that is continuously influenced by the experiences we have, the things we own, the environment we live in, and the people we interact with. “Wú”, on the other hand, is employed for

self-expression independent of "others". It represents the authentic self, embodying many positive qualities. While the embodied identity (“Wǒ") sways to the rhythms of the world, the conscientious self (“Wú”) is rather steadfast and synchronizes with the beats of the Nature (Dao - 道).

THE DYNAMICS BETWEEN THE AUTHENTIC SELF “WÚ - 吾” AND THE SELF-CENTERED “WǑ - 我”

The tale of Wǎng Liǎng Wèn Jǐng ( 罔两 问景 ) paints a picture of inseparable bond between Wǒ - 我 ” and Wú - 吾 . Wǎng liǎng (罔两) is the elusive faint shadow beyond the periphery of the silhouette (Jǐn - 景 ). Wǎng liǎng questions Jǐn, asking, "Do you only move when your master moves? Do you lack your own consciousness?" Jǐn responds, "I am bound to follow my master's movements. No different than a snake relies on its scales and a cicada needs its wings”.

Wú and Wǒ are inseparable, much like the two intertwined shadows. The ego self (Wǒ) is the vulnerable one in the duo. Constant skepticisms, arguments, comparisons, fear, materialism, pride, fame, and external validation disrupt its well-being, leading it astray from Wú, which displays kindness, righteousness, respect, and trustworthiness. The conflict creates ongoing disturbances in their relationship and the world around them.

EMBRACING QÍWÙ’S (斉物): THE MINDSETS BEHIND THE SCENES

Zhuangzi's notion of sàng wǒ (丧我), which translates to "loss of self," closely mirrors Laozi's concept of the "true self without the body" (wú wú shēn - 吾无身) (Passage 13 of Tao Te Ching). In this framework, wú shēn (无身) and sàng wǒ (丧我) encourage us to avoid being swayed by external circumstances and make sound decisions based on values and principles.

Zhuangzi’s mindset of non-reliance (Wù dài - 无待) and Laozi’s teaching of letting go (Fú shì - 弗恃 & Bù shì - 不恃 , as expressed in Passages 2 and 10 of Tao Te Ching) help shed narrow perspectives and embrace the interconnectedness of Qíwù ( 斉物 ). These principles cultivate inner peace and help navigate life’s challenges with grace and integrity.

Rewiring the Selfish Wǒ “我: From Isolation to Reconnection.

Zhuangzi associates the corrupted Wǒ (我) with Xiǎo zhī (小知), who exudes inflated egos and disgruntled noises (Rén làng - 人籁) reminiscent of the mournful echoes of human artifice. They employ sneaky tactics and engage in endless arguments. Finding faults in others and passing judgment are their specialties. Their narrowmindedness resists alternative perspectives. Emotionally, they are impulsive, quick to anger, reckless, yet harbor profound insecurity. Zhuangzi imparts a serious prognosis to Xiǎo zhī (小知), exhibiting an inflated sense of self-importance.

Qíwù lùn ( 齊物論 ) focuses on correcting Wǒ's distorted perceptions of the world, others, and itself. By addressing issues like self-righteousness and self-importance that cloud Wǒ's judgment, Qíwù lùn paves the way for the true self consciousness (Wú) to reconnect with the outside world.

QÍWÙ (斉物):

TRANSCENDS THE LIMITATIONS OF SUBJECTIVE THINKING.

Zhuangzi's idea of Qíwù (齊物) emphasizes the interconnectedness of all things in the universe. Interconnectedness transcends the limitations of subjective concepts such as “good and bad”, “me and others”, and “right and wrong”, which often have no universal standards or references for judgment. Qíwù develops a deeper sense of empathy for others in four areas.

1)Transcend good and bad (qí shì fēi - 斉是非) to appreciate others with different values without imposing our own. It fosters openminded, objective dialogue, and embracing a willing and curious mindset to engage with diverse perspectives.

2)Transcend egocentrism (qí bǐ cǐ - (斉彼此) to emphasizes unity, collaboration, and mutual support in the pursuit of common goals.

3) Deemphasize materialism (qí wù wǒ - 斉物我) to foster interconnectedness to all things in nature while acknowledging that each entity possesses its own distinct perspective. This concept helps to break down barriers of prejudice and promote mutual understanding.

4)Surpassing the fear of live and death cycle (qí sǐ sheng - 斉生死) redirects our attention from mere existence to fully living and experiencing life with greater intensity and appreciation. By challenging assumptions, embracing diverse perspectives, and approaching complex issues with an open mind, these strategies promote a more equitable and fair understanding of the world. These fundamental shift in attitude dismantles the self-importance and selfrighteousness (zì yǐ wéi shì - 自以为是) characteristics of a Xiǎo zhī (小知), paving its way to become a wiser person (Dà zhī - 大知).

Residing in San Diego with roots in Hong Kong and Taiwan, Herbert bridges the gap between science and art. By day, he works as a biotech professional, but his true passion lies in expressing himself in acrylic paintings and introspective writings. Herbert's paintings of landscapes, seascapes, and soaring birds capture the essence of nature's tranquility and power. Inspired by the wisdom of Zhuangzi and Laozi, he delves into themes often overlooked in our fast-paced world: self-reflection, interconnections, and the true essence of life. Through his art and writing, Herbert invites viewers on a journey of mindfulness, offering a deeper understanding of life's complexities and a path toward a more fulfilling existence. https://twitter.com/RubiconMFA