i

By Dan Tracy

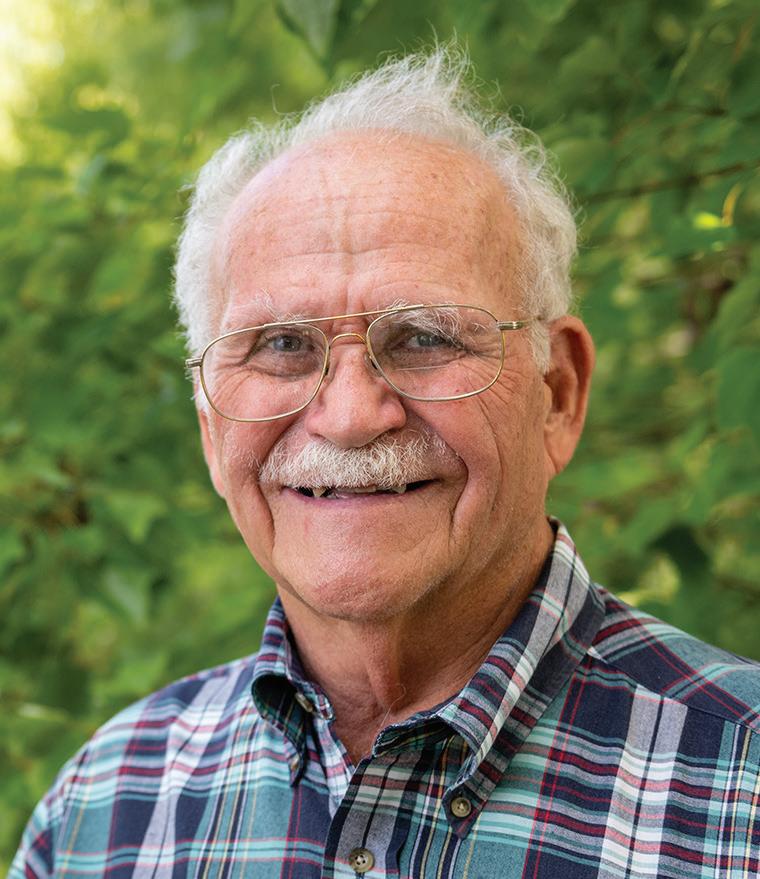

Author Dan Tracy

Photographer Judy Watson Tracy

JUDY WATSON TRACY PHOTOGRAPHY judywatsontracy.com

Graphic Designer and Illustrator

Jill Shargaa

SHARGAA ILLUSTRATION & DESIGN shargaa.com

Developmental Editors Amanda Day Dori Madison DAY COMMUNICATIONS daycommunications.com

Cover photo by Judy Watson Tracy

Copyright 2024

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without permission by the publisher, except for brief, attributed quotations. Printed in the United States of America. Published by Central Florida Expressway Authority.

ii iii

iv

A Note from the Author by Dan Tracy ............................................................................. pg vi What, Why and Where ................................................................................................. pg viii Wekiva Parkway Timeline ............................................................................................. pg xii The People Behind the Wekiva Parkway ......................................................................... pg xiv CHAPTER 1 Remarkable Events Shaped Parkway.............................................................................. pg xvi CHAPTER 2 The Wekiva River: ‘To See It Is to Save It’ ......................................................................... pg 6 CHAPTER 3 Beltway and Wekiva Concepts Born in 1950 .................................................................... pg 12 CHAPTER 4 The 1980s Had it All: Star Wars, Conventioneers, Christmas Freeze and Bonds ..................... pg 18 CHAPTER 5 A Long Time Coming: The Beltway Begins During the 1990s ............................................. pg 24 CHAPTER 6 Governor Bush Gets Serious About the Wekiva Parkway ................................................... pg 32 CHAPTER 7 Early 2000s: Neighbors Learn the Wekiva Parkway Really Is Going to be Built ...................... pg 36 CHAPTER 8 Central Florida Expressway Authority Created to Build Roads Throughout Region ................ pg 44 CHAPTER 9 Wekiva Parkway Construction Begins the Same Year as Pro Soccer Comes to Orlando ............ pg 50 CHAPTER 10 Wekiva Parkway Designed to Protect Water, Environment, Wildlife, Lessen Congestion......... pg 54 CHAPTER 11 Blue Ridge Parkway Model for Wekiva Parkway ............................................................... pg 62 A Final Note by Laura Kelley ....................................................................................... pg 72 v

What’s Inside

The River and the Road

Let me be frank. I never expected to write The River and the Road. The Story of the Wekiva Parkway. It wasn’t that I was unfamiliar with the subject matter. During my three and a half decades as a reporter at the Orlando Sentinel, I covered the Central Florida Expressway Authority (CFX) for more than 10 years, spread over two different time periods. I knew the players and the issues well.

Wekiva Parkway plans and the start of construction were among the many stories I wrote about the authority. It’s just that some of the other stories I wrote were considerably less than flattering. Think grand jury and comptroller investigations, forced resignations, questionable political fund-raising. I also detailed in print quite a bit about toll increases that few drivers enjoy paying.

Of course, those kinds of stories come with the territory as a reporter because you are duty bound to cover the good and the bad on your beat.

My goal in every story was to report the facts in as balanced and fair a manner as possible. That sounds good in theory, but often results in

people on either side — or sometimes both — berating the writer.

To this day, there are people who remain angry at me about stories I wrote years ago. I figured there could be ill will lingering toward me within the authority walls as well. So I was surprised when I was approached during the pre-Covid days about telling the story of the Wekiva Parkway. Even more astonishing to me was the fact that the authority put no restrictions on the questions I would ask, the records I would review or the way I would write this piece. That made this assignment possible, in my estimation.

Now, a little background.

My first tenure covering the authority was during the 1980s, when CFX was called the Orlando Orange County Expressway Authority (OOCEA) and its headquarters was an old insurance building directly beneath State Road 408 on the south edge of downtown Orlando, by Lake Lucerne. The authority’s toll road network then was in its infancy, comprising SR 408, then known as the East-West Expressway, and SR 528, then called

the Bee Line Expressway. The late Bill Gwynn was the executive director at the time.

My second stretch started in 2007 and ended in December of 2015, when I left the Sentinel. By then, the authority’s jurisdictional duties had been expanded to include three additional counties.

Like many involved in transportation during my first tour of duty at the authority, Gwynn was a plain speaker bordering on brusque, given to going from Point A to Point B in as straight a fashion as possible, whether it was building a road or discussing the topic of the day. The business was male-dominated and exceedingly bottom-line oriented.

Phil Reece, who I interviewed for the book, was the board chairman then. Along with Gwynn, consultants such as Keith Denton and others, Reece made the transformative decision to change the way the agency financed its roads. Instead of borrowing money for a singular road then paying it back with the resulting tolls, they decided to sell bonds that could be spent on the entire system. That allowed for a more

accelerated way to fund and construct what is now a 125-mile system that continues to grow.

Like most organizations, government or private, success or failure often comes down to what at the time might seem to be an insignificant decision. Without that bonding change, the authority would not have been in the position to keep expanding its roads to accommodate nonstop growth in the region. That includes completing the beltway around Metro Orlando, plus its longmissing link, the Wekiva Parkway. Through the years since its founding in 1963, the agency has had its share of controversies and bad headlines — again, a fair bit of which I covered. There’s no need to go into all the details, but suffice it to say some wounds at the authority were self-inflicted while others were the result of outside forces.

Given that history, I would not have accepted this assignment if I did not believe that the current management and leadership of the agency was intent on operating for the common good of the community.

Interestingly, the top executive team, or C-Suite, at the authority while I wrote this book was predominantly female, led by CEO Laura Kelley, who retired in February 2023. She was replaced by

her chief of staff, Michelle Maikisch, who continues Kelley’s legacy with the support of the authority’s Chief Financial Officer Lisa Lumbard and Chief of Infrastucture Glenn Pressimone, among others. They all appear committed to elevating the environmental standards of the authority’s road projects, with the Wekiva Parkway setting the benchmark. Together they have set an ambitious sustainability program, which was not much more than a whisper at the authority a decade ago, much less when Gwynn was on board.

Where, when and how new expressways are built will invariably be met with cheers as well as opposition. That is understandable

and largely unavoidable. Nobody wants to live near an expressway, no matter the design or need.

But as the Wekiva Parkway shows, large toll road projects can — at least occasionally — bring together often conflicting constituencies — think environmentalists and expressway builders — in a common cause.

My hope with this book is that readers might better appreciate the human side of how megaroads are planned and built, at least here in Central Florida. For transportation industry professionals, I tried to capture the essence of the complex work they do without too much technical jargon so everyday people might appreciate the story.

vii

A Note from the Author

vi

Author Dan Tracy, on the Wekiva River.

What, Why and Where Behind the Wekiva Parkway

WHAT

At a total of 25 miles long, the Wekiva Parkway is the final segment of the tolled expressway beltway around Metro Orlando. Think of the Wekiva Parkway as being between 10 and noon on a clock, with downtown Orlando sitting in the middle of the dial. The $1.6 billion parkway project links the northwest corner of metro Orlando to other major corridors in the eternally growing region. Most importantly, the parkway connects near Sanford with Interstate 4, the main thoroughfare in all of Central Florida.

WHY

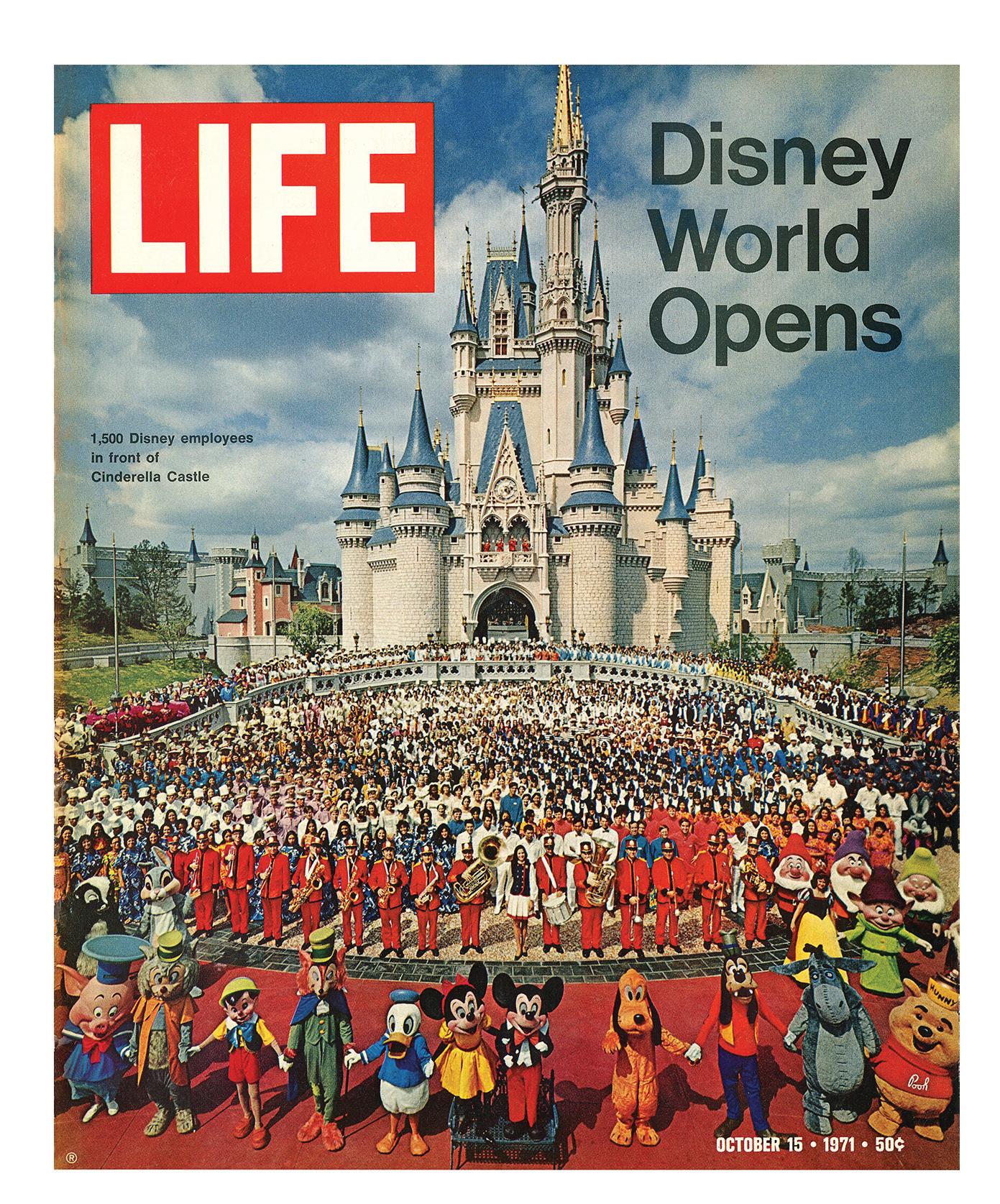

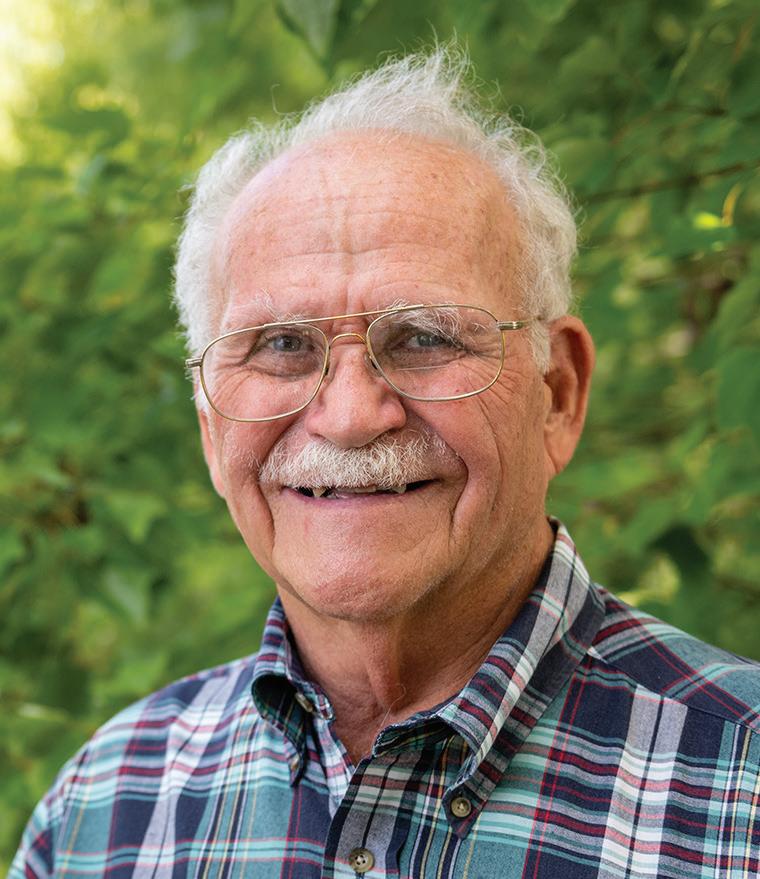

New residents, multitudes of tourists and untold volumes of workers were drawn to Central Florida by the Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World, which was announced in 1965 and opened in 1971. Also with a burgeoning defense and space sector sparked by NASA’s race to the moon during the 1960s also helped Metro Orlando grow from about 400,000 residents then to a full-time population nearing 2.75 million in 2022 — a more than eight-fold increase in year-round

residents. A record 75 million tourists visited Metro Orlando in 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Visitors are again flocking to the region, setting new records.

Due to its small-town roots and paucity of expressways, Metro Orlando’s transportation network was in danger of being overrun with the advent of Disney and related tourism impacts. Toll roads were the quickest, most cost-effective answer, local leaders decided. That led to the 1960s and early 1970s construction of the East-West Expressway, now SR 408, to move people quickly east and west of downtown Orlando, and the Bee Line Expressway, now SR 528, the corridor bridging the new tourism areas to the Space Coast.

Work on the beltway started in earnest during the 1990s, some 40 years after community leaders and transportation experts first decided such an expressway system would one day be necessary.

The last, most complicated and expensive link of the beltway – the Wekiva Parkway — got underway in 2015. The biggest issue facing the Wekiva

Parkway was selecting an alignment over the ecologically sensitive Wekiva River and across its surrounding basin.

Those environmental worries had effectively shelved any serious discussions about building the road for decades, to the point that the Wekiva Parkway was once dropped from the list of potential construction projects by the region’s main transportation planning organization, MetroPlan Orlando.

The Wekiva Basin, fed by 19 springs connected to the Floridan Aquifer, was shielded from rampant development by a 1988 law passed by the state Legislature. It said, in part, that the Wekiva River was “a natural resource of state and regional importance.”

Acutely aware of the environmental concerns, designers and engineers created a complex construction plan that minimized potential development near or in the basin as well as any impacts on the river, including building a bridge with no pillars in the water, and putting up temporary berms to keep construction runoff from spilling into the river.

CENTRAL FLORIDA REGIONAL BELTWAY MIAMI JACKSONVILLE GAINESVILLE WEST PALM BEACH FORT LAUDERDALE TALLAHASSEE FORT MYERS TAMPA ATLANTIC OCEAN 10 10 95 95 95 4 ORLANDO FLORIDA’S TURNPIKE 1 A1A 95 Orlando Deltona DeLand Titusville New Smyrna Beach Rockledge Clermont St. Cloud Poinciana Polk City LAKE COUNTY BREVARD COUNTY 528 417 417 408 429 429 429 see detailed Wekiva Parkway map on pg. xi 4 4 46 MAP KEY CENTRAL FLORIDA REGIONAL BELTWAY WEKIVA PARKWAY FLORIDA MAP Major Parkway System

ix

viii

WHERE

The Wekiva Parkway is the final northwest leg of the Central Florida

x The expressway authority was first with its commitment to build the Wekiva Parkway. Beginning in 2012, the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) became a partner when it was clear that a joint effort was needed to complete the highly complicated and expensive last leg of the beltway.

Regional Beltway built to support commercial and visitor traffic in north Orange County, west Seminole County and southeast Lake County. The expressway authority and FDOT worked together to complete the planning studies. That led to an agreement between the two entities to each design and construct a portion of the parkway. The expressway authority constructed 10 miles of the southern portion and the northwest

curve, while FDOT took over the remainder of the beltway with an allimportant connection to I-4.

CFX broke construction of its Wekiva Parkway commitment into five easier-to-manage segments to keep the entire project moving. That included building some smaller connector roads to feed traffic to and from the Parkway. FDOT completed the final segment of the Parkway Jan. 27, 2024.

441 441 192 192 17 27 27 27 1 1 17 92 17 92 520 434 436 44 46 46 46 44 420 50 50 33 19 19 4 4 4 95 FLORIDA’S TURNPIKE FLORIDA’S TURNPIKE 95 Orlando Winter Park Sanford Deltona DeLand Titusville New Smyrna Beach Rockledge Altamonte Springs Oviedo Apopka Eustis Mount Dora Clermont Kissimmee St. Cloud Poinciana Polk City Winter Garden 429 429 429 414 417 408 417 528 528 Orlando International Airport Walt Disney World Sanford-Orlando International Airport WEKIVA PARKWAY ORANGE COUNTY ORANGE COUNTY OSCEOLA COUNTY POLK COUNTY LAKE COUNTY LAKE COUNTY BREVARD COUNTY SEMINOLE COUNTY MAP KEY REGIONAL BELTWAY WEKIVA PARKWAY HIGHWAY COUNTY LINE WEKIVA BELTWAY C entral Florida Section xi

First public mention about building a beltway around Metro Orlando

Wekiva Parkway Planning, Design & Engineering Study began Gov. Jeb Bush created the Wekiva River Basin Commission to determine alignment Wekiva Parkway rst concept design approved Walt Disney World opened, triggering unprecedented growth and the need for more expressways

Florida Legislature created the Central Florida Expressway Authority (CFX) and expanded jurisdiction CFX completed construction of its Wekiva Parkway segments 18 months early

Orlando Orange County Expressway Authority

(OOCEA) created, board envisions regional beltway OOCEA changed its public nance structure so bond monies cound fund an entire system of roads

The Wekiva River was designated a “national wild and scenic river” by U.S. Congress

The Wekiva Parkway and Protection Act was passed by the Florida Legislature Wekiva Parkway completed as the nal link of the Central Florida beltway CFX began construction on its Wekiva Parkway segments The Federal Highway Administration approved Wekiva Parkway alignment and design

Seven

1950 1971 1986 2003 2005 2014 2018 1963 1983 2000 2004 2012 2015 2024

D ecades in the Making: The Wekiva Parkway from Star t to Finish

xii xiii

The People Behind the Wekiva Parkway

Roads typically are made of asphalt or concrete.

Motorists rarely give them much thought other than as a way to get where they are going. But every road has a story behind it, one that involves countless people.

The Wekiva Parkway is no exception. It is impossible to list everyone who played a role in its creation, starting some 70 years ago with the original discussion to build a beltway encircling Metro Orlando.

As the final link in the beltway, the Wekiva Parkway would not exist without the efforts of thousands of men and women, from planners and engineers, construction workers and heavy equipment operators to transportation technology installers and landscapers. They all contributed time and effort, sweat and even a few tears to the Parkway.

Those pictured on these pages are among the many who made the Wekiva Parkway possible, going from an idea to major part of Central Florida transportation network.

Expressway Authority Board Members, Elected Officials and FDOT Partners

Community and Consultant Partners

xv

xiv

Mike Snyder, P.E., 2004-2011, Executive Director

Glenn Pressimone, P.E., 2008-Present, Currently serves as Chief of Infrastructure

Laura Kelley 2006-2023, Retired as Executive Director 2023

Joseph A. Berenis, P.E., 1988-2019, Retired as Chief of Infrastructure 2019

Ben Dreiling, P.E., 2000-Present, Currently serves as Director of Construction

Max Crumit, P.E., 2012-2013, Executive Director

Former and Current Expressway Authority Employees

Elaine Rejimbal Mount Dora resident, frequent user of Wekiva Parkway

Terri Rejimbal Wekiva Parkway 5K female winner

Charles Lee Audubon Florida Director of Advocacy

Mary Brooks Wekiva Parkway Outreach Consultant, Quest Corporation of America

Phil Reece 1985-1987, Board Member 1987 Board Chairman

Allan Keen, MBA, 2002-2007, Board Member 2007 Board Chairman

Andy Gardiner 2014-2016, President of the Florida Senate Walter Ketcham, Esq., 2010 -2014, Board Member 2014 Board Chairman

Lee Constantine 2020-2022, Board Member Currently serves as Seminole County Commissioner and as Chairman of the Wekiva River Basin Commission

The expressway authority was created by the Florida Legislature in 1963 as the Orlando-Orange County Expressway Authority (OOCEA). OOCEA had jurisdiction in only Orange County. In 2014, the Florida Legislature changed the name from OOCEA to the Central Florida Expressway Authority (CFX) and extended its jurisdiction to four counties: Brevard, Lake, Orange, Osceola and Seminole. In 2017 the Legislature added a fifth county, Brevard, to CFX’s jurisdiction.

Ananth Prasad, P.E., 2011-2015, FDOT Secretary

Remarkable Events Shaped Parkway

1

chapter xvi 1 Wekiva Parkway Systems Interchange of SR 429 & SR 453

Remarkable Events Shaped Parkway

Hailed as a model for road building throughout the state of Florida and the country because of its sensitivity to the environment, the Wekiva Parkway became reality only after a series of remarkable events took place during the course of 70 years. They include:

• A long-ago tweak — during the mid-1980s — to public finance rules that created a way to help the expressway authority pay for its share of what would end up being a $1.6 billion undertaking.

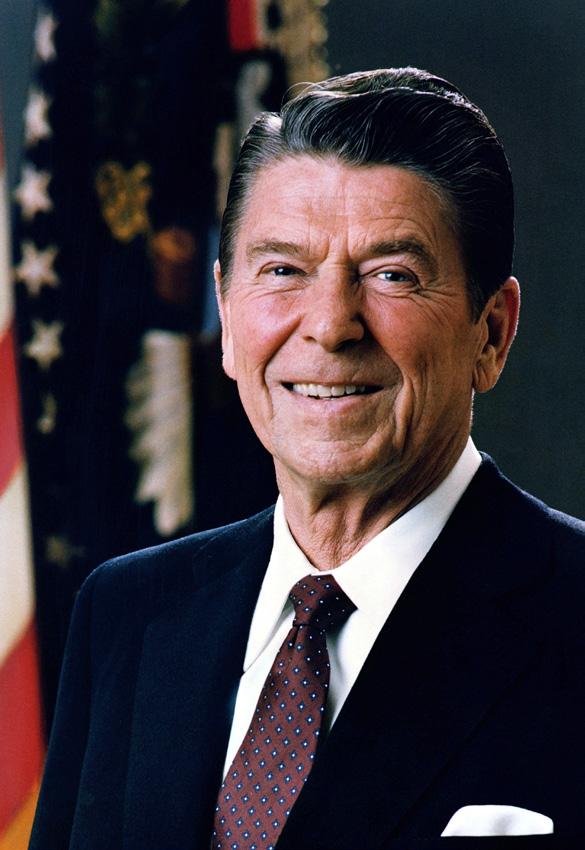

• The courting of former Gov. Jeb Bush by the thenexpressway authority board chairman, Allan Keen during the early 2000s on behalf of the Wekiva Parkway.

Keen not only convinced Bush to support the concept, but also to create a panel of community members to devise and set into law the rules for how and where the road would be built.

• A consensus reached between what was then seen as the unlikeliest of allies: transportation planners, road builders and environmental champions who were protective of the Wekiva River Basin, a vast and fragile

ecosystem that is home to black bears and abundant wildlife and acts as a major water recharge area for Central Florida.

• An old, scuffed Louisville Slugger baseball bat. Yes, you read that correctly. Be patient and we’ll get to it a little later.

The bottom line: A variety of forces came together over many years to put the common good above competing interests, transforming the Wekiva Parkway from a conceptual blue-line drawing pinned to a wall into the final, crucial link of a longcoveted beltway encircling Metro Orlando.

Fencing runs along much of the Wekiva Parkway, separating traffic from wildlife. Sections of the road have been elevated to allow wildlife to safely cross beneath.

Joseph Berenis, who oversaw the design and construction of the Wekiva Parkway as chief of infrastructure, described the process as: “It’s something that doesn’t happen too often…this is a result of everyone working together. It’s proof we can all work together to get the job done.”

Alan Hyman, who worked with CFX on the Wekiva Parkway as the director of transportation operations for FDOT, said about the project, “This really shows how we could get together all the stakeholders, local agencies, environmentalists, to get something done the right way.”

3 2

Charles Lee

Video of Charles Lee

CFX and FDOT: An Enduring Partnership

Since its inception as a tolling agency, the expressway authority has worked closely with FDOT on numerous road projects, including the Wekiva Parkway and the beltway. In fact, a former top FDOT administrator, Mike Snyder, left the state agency in 2004 to join the expressway authority as executive director. He played a critical role in crafting the pact between FDOT and the expressway authority to build the Wekiva Parkway.

“We didn’t let any of it slip. It was very deadline driven,” said Ben Dreiling, CFX’s director of construction and maintenance.

As shown on the adjacent map, Sections 1A and 1B cover five miles and opened to traffic July 27, 2017. Section 1A begins where SR 429, also called the Daniel Webster Western Beltway, ends at US Highway 441, near Apopka. Section 1B extends from near Ponkan Road to Kelly Park Road. This part of the Wekiva Parkway provides a muchneeded alternative to local roads.

Sections 2A, 2B and 2C are located between Kelly Park Road and SR 46, and between Round Lake Road and County Road 435 (Mount Plymouth Road). Those segments are in southeast Lake County (2C) and northwest Orange County (2A, 2B). Work began on those sections in 2016 and opened about a year ahead of the original schedule in 2018. Those segments connect to FDOT’s Sections 4A and 4B, which also opened in 2016. With that link, the expressway authority’s Wekiva Parkway sections created two new expressway junctures to well-traveled SR 46 for communities throughout Lake, Orange and Seminole counties.

As many as 6,300 trips a day were expected on this stretch during the first year. By April of 2018, more than 16,000 trips were occurring during the work week.

The last and final CFX Wekiva Parkway segment that opened in 2018 marked a major corridor-wide milestone: More than half of the 25-mile Wekiva Parkway was open to traffic, including work done by the FDOT.

The Wekiva Parkway has two connections from the systems’ interchange to SR 46: One near Round Lake Road, and the other east of Camp Challenge Road. These SR 46 connections opened on March 31, 2018.

The first parts of the Wekiva Parkway to open were constructed by FDOT. At a total of 3.14 miles, Sections 4A and 4B were completed Jan. 20, 2016, from County Road 435/Mount Plymouth Road northeast to Old McDonald Road, ending in an interchange with State Road 46. FDOT chose that section to start because it already owned the land.

In mid-May 2022, FDOT opened more than six miles of the Wekiva Parkway largely along the existing SR 46 corridor, from SR 429 to just west of Longwood-Markham Road. The segment — known as Section 6 — includes a nontolled, service road for local travel, new bridges over the Wekiva River, along with several wildlife bridges to allow animals to pass safely between the Seminole State Forest and Rock Springs Run State Reserve and a multi-use trail for cyclists, pedestrians and horses.

FDOT Sections 7A and 8 were completed in 2022. This includes the final portion of the Wekiva Parkway that linked with I-4 was completed in January 2024.

“I am proud of the way FDOT helped lead the way for responsible and sustainable development,” said Jared W. Perdue, the former FDOT District 5 secretary. The FDOT District 5 jurisdiction covers the Wekiva Parkway and most of Central Florida.

4 Lake Apopka ORANGE COUNTY LAKE COUNTY SEMINOLE COUNTY WEKIVA PARKWAY Construction Sections WOLF BRANCH RD ONDICH RD HAAS RD KELLY PARK RD PONKAN RD WELCH RD WEKIWA SPRINGS RD ROCK SPRINGS RD VICK RD ORANGEBLOSSOMTRAIL PLYMOUTH SORRENTO RD YOTHERS RD ROUND LAKE RD OLDDIXIEHWY 441 441 17 92 46 46 46 46 435 437 437 436 414 434 429 429 429 451 429 453 4 4 MAP KEY SECTION 4A SECTION 2B SECTION 2A SECTION 1B SECTION 1A SECTION 6 SECTION 4B SECTION 7A SECTION 8 CENTRAL FLORIDA REGIONAL BELTWAY

5

7 2

See It

to Save

chapter 6

The Wekiva River: ‘To

Is

It’

The Wekiva River: ‘To

See

It Is to Save It’

The Wekiva River predates recorded history.

Meandering from east to west, as well as a bit north and south, it runs for 16 miles in Central Florida. The river serves as a meeting place where a warm temperate climate meets a subtropical one, creating and supporting a vital ecosystem and biodiversity that is primordial.

It has been designated a Florida Outstanding Water, a Florida Canoe Trail, an Aquatic Preserve and a National Wild and Scenic River.

But to Wekiva River champion Nancy Prine, it is something much simpler: A link to Florida’s past — long before theme parks and widespread development, the advent of air conditioning, and even before Ponce de Leon first set foot in Florida in 1513.

“It is an area in Central Florida that is natural…It gives us a hint of how Florida was formed,” said Prine, a longtime member of the Friends of the Wekiva, a group dedicated to protecting the river and basin.

Located in three counties — Orange, Seminole and Lake — the river and its basin encompass more than 135 square miles. The river largely follows the county line between Orange and Seminole counties.

The Wekiva derives its name from the word the Creek and Seminoles tribes used to say “spring”. It originates in Apopka and flows into the St. Johns River in DeBary, a city 26 miles north of downtown Orlando. Its main stem joins with three tributaries, Rock Springs Run, Blackwater Creek and the Little Wekiva River.

As Prine observed, the Wekiva is one of the few river systems in Central Florida that remains relatively unsullied by the continual growth of Metro Orlando. In that sense, the river and surrounding wetlands are akin to a living natural museum exhibit.

“It is so important for all of us to recognize what Florida was like in the past,” she said.

Protecting the river and basin became priority No. 1 when the expressway authority started the process to design the Wekiva Parkway during the early 2000s. Said Allan Keen, the expressway authority chairman at the time: “We’re just going to have to do what it takes. We’re not going to blow through (the Wekiva Basin) and destroy it.”

That commitment won the support of Prine and other environmentalists. Prine said the accommodations the expressway authority and FDOT made to protect the basin are “a tremendous thing for the environment.”

The two agencies made and carried through on several major promises, including:

• Reducing potential development in the area — and the possible destruction of critical water recharge areas — by restricting the number of major, new interchanges to one and buying and setting aside more than 3,400 acres of land for conservation.

• Constructing the three-deck bridge with a “topdown” method to minimize impacts on the river. In many bridge projects, crews stage in the waterway itself during construction. But FDOT

officials agreed to employ large traveling concrete forms powered by a hydraulic system to create the bridge from above. The approach took more time but resulted in less disruption to the wildlife that frequent the habitat.

• Eschewing bridge piers in the water. The bridge is the equivalent of a six-story building that is much higher off the river than its predecessor, with the goal to reduce potential damage to the ecosystem and allowing unfettered access for aquatic life and boaters. The piers of the new bridges are designed to resemble tree trunks and not monolithic concrete pillars.

Keeping the Wekiva River clear of obstructions is critical to canoe, kayak and paddle board enthusiasts, as well as men and women who regularly fish the waterway. On the river, they are able to immerse themselves in nature, isolated from the sounds and commotion of the workaday world. Prine approves of the new bridge, saying it opens up the river to recreational users, as well as wildlife, providing unobstructed views and water flow. “You can enjoy going through that passage,” she said.

9

8

Several of the streams are clear because they are spring-fed. Others are blackwater, which receive most of their flow from precipitation resulting from bank overflows. The Wekiva and its tributaries are in superb ecological condition, environmentalists maintain.

The original spelling for the river in 19th Century maps was Wekiwa, but developers switched out the ‘w’ with a ‘v’ over time, making the pronunciation easier in their estimation.

Native Americans, primarily the Timucua and Tocobago tribes, hunted and fished along the Wekiva for hundreds of years. The Timucua and Tocobago peoples were absorbed into the Seminole tribe during the 1800s.

The river and basin — then and now — are home to a plethora of plants and animals, many considered endangered, threatened or of special concern. Among them: the wood stork, which nests in cypress trees in and along the river; the limpkin, the little blue heron, the gopher tortoise, the Florida black bear, the bald eagle and the alligator.

The river itself has teemed with a wide variety of fish through the years, including striped bass and sunshine bass, largemouth bass, monster catfish, shellcrackers, red breasted sunfish, black crappie, bluegill, blue tilapia, bowfin, brown bullhead, chain pickerel, channel catfish and Florida gar.

Drawing its water from the Floridan Aquifer, the drainage of its watershed and more than 34 named springs, the river varies widely in width, from as much as three miles across to a few dozen yards in places.

As Wekiva River champion, former CFX board member and Seminole County Commissioner Lee Constantine has long argued, “To see the Wekiva is to save it.”

Headstone of Civil War Soldier, Former Slave Lies Near Parkway

The white marble gravestone of Civil War veteran and former slave Anthony Frazier lies on its back in long grass on a slight rise, slender trees providing a bit of shade. Little more than 1,500 feet away from the marker is the Wekiva Parkway, a 300foot-wide toll road where cars and trucks stream by, heading to and from northwest Orange County, southeast Seminole County and Interstate 4.

Motorists have no way of knowing that they are passing a largely forgotten bit of history because somewhere in the scrub lands surrounding the Parkway — possibly in a conservation area known as Neighborhood Lakes, near Sorrento — may well lie the remains of Anthony Frazier, a slave who ran away from his Central Florida citrus plantation to fight for his freedom on the Union side of the Civil War.

Frazier’s story is fascinating, though frustratingly incomplete, because records of his life are scarce. For instance, no one knows where Frazier actually is buried. Over time, his tombstone was separated from his plot. Only a few people are aware of the exact whereabouts of his marker, which essentially is beyond the reach of anyone without a four-wheel-drive vehicle and pinpoint knowledge of its location.

The stone, which does not hold his date of birth or death, was discovered by the former landowner a few years before Parkway construction began. He placed the stone next to a tree because he felt it seemed wrong to move it.

At one point, a potential alignment of the road would have caused the marker to be relocated, but the ultimate route was shifted, leaving the stone safe.

Alerted to its existence, the expressway authority commissioned a ground surface reconnaissance of the area as part of an archaeological field survey. The review did not find any other stones or depressions which might suggest an unmarked grave.

Research by the Orlando Sentinel, genealogists and amateur historians pieced together parts of Frazier’s life, including that he ran away during his late 20s from a Rock Springs citrus plantation. He joined the Union Army in 1864, one year before the war ended.

Accompanied by his fellow slave and half-brother, Joseph Robards, Frazier signed up in Hilton Head, S.C. They were assigned to Company K of the 21st U.S. Colored Infantry.

They were among the nearly 180,000 Blacks who served in the Union Army inspired by the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. Roughly 40,000 Black men died during the war.

As privates, Frazier and Robards fought in numerous skirmishes, among them a major battle in Jacksonville. The pair survived the war and were honorably discharged April 25, 1866, returning to Central Florida to start their lives over again — not as slaves, but as free men.

The two came back to the area most likely because they knew the land and people. Frazier was a farm hand and carpenter, according to a statement made in 1910 by Robards that is kept at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Robards was speaking for Frazier’s widow, Mary. At the time, she was asking for the $8-a-month military pension of her just-deceased husband.

Mary was younger than Frazier, possibly by as much as 15 years, records indicate. She met him when he was camping as a soldier in Charleston, S.C. They were married in Jacksonville after Frazier left the service.

Mary and Anthony may have had as many as six children

and the family settled near Lake Beauclair in the Tangerine area of Orange County, about 12 miles west of where the headstone was found. Frazier was granted 160 acres through the Homestead Act, with the papers signed by President Ulysses S. Grant. The land was worth $600 when Mary Frazier died in 1925.

The couple were well respected in their community, earning the nicknames of Uncle Pete and Aunt Mary, according to an entry on the Ancestry.com website. It is not clear what claimed the lives of Anthony and Mary Frazier. Their descendants appear to have left the area. A graveyard just outside of Eustis holding the remains of Black people has a marker bearing the name of Lula Frazier, who was born in 1881 and died in 1926. She might have been Frazier’s second-youngest daughter, or the wife of his youngest son, Robert, who was born in 1879.

Their true relationship to Anthony Frazier may never be known, just like the whereabouts of his final resting place, hard by the Wekiva Parkway.

10

The headstone of Civil War soldier Anthony Frazier is propped against a tree. Photos courtesy of Mark Thrush.

11

Beltway and Wekiva Concepts Born in 1950

3

12 13

chapter

Workers put the finishing touches on the underside of the bridge over the Wekiva River during early morning hours.

Beltway and Wekiva Concepts Born in 1950

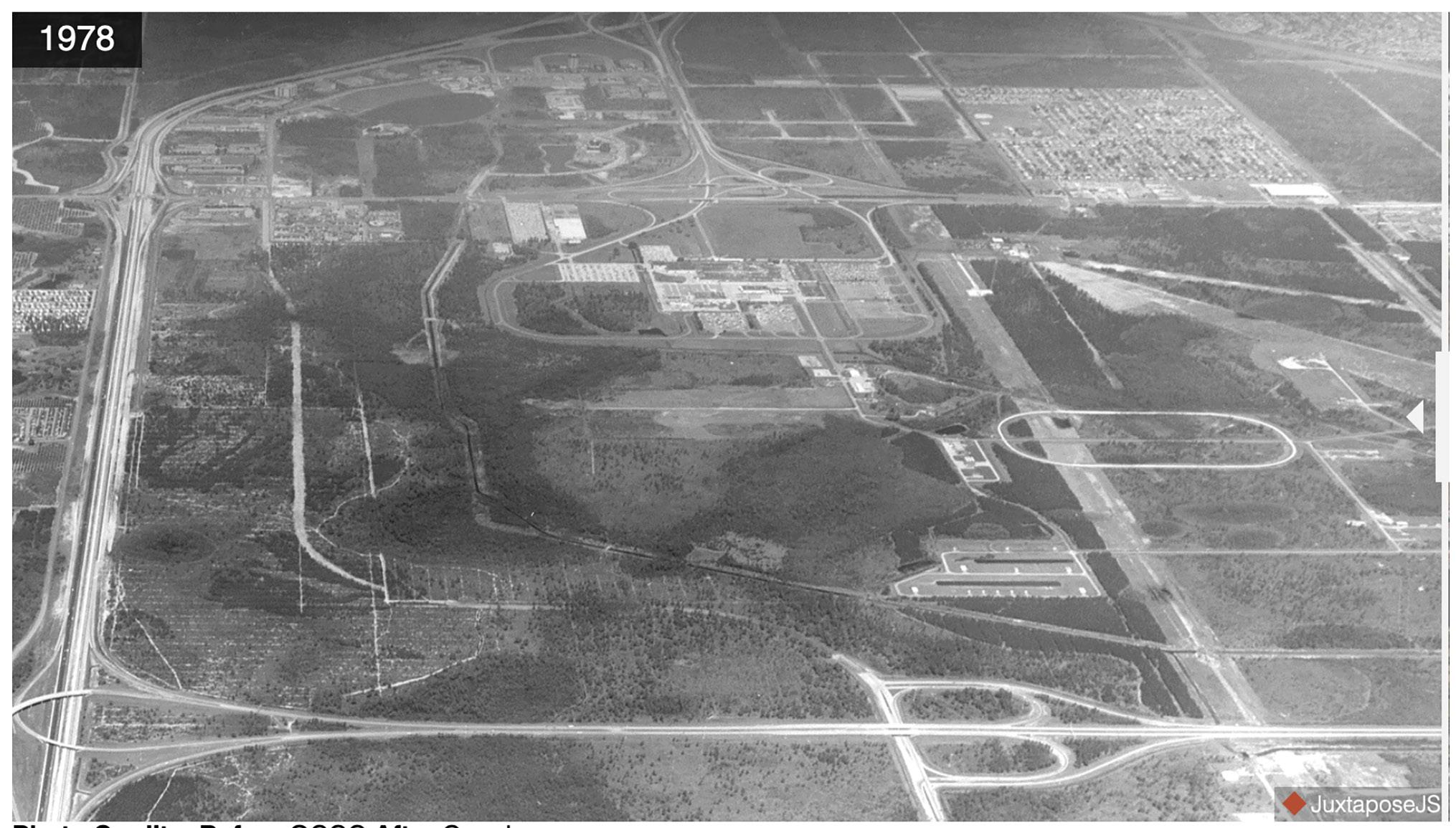

The idea of the Wekiva Parkway and a beltway around Metro Orlando stretches for some seven decades, going as far back as 1950, when a gallon of gasoline cost 27 cents and the proposed road was called the “Outer Belt Loop.” It would encircle much of Metro Orlando and was envisioned to be 35 miles long. At that time, the entire beltway was estimated to cost $4 million.

One of the most prominent public mentions of the beltway occurred some 13 years later during the inaugural meeting of the Orlando Orange County Expressway Authority, the toll road building agency that preceded CFX. Gasoline had jumped seven cents to 34 cents a gallon by

1963, which also was the year the Plaza Theater on Bumby Avenue opened by showing the John Wayne movie McLintock!.

The agency’s board members said a beltway, including the Wekiva Parkway, would have to be built one day because almost all major metro areas in the country had such a road system. Beltways were crucial to large, growing communities, they said, because they speeded the delivery of vital goods and services and took cars and trucks off local and secondary roads, freeing them of excess traffic to better serve businesses and community hubs.

A beltway, though, might have seemed a tad presumptuous to many observers because less than 400,000 people called Central Florida home during the 1960s, with about 60,000 of them living in Orlando. Traffic congestion then meant occasionally having to wait for a traffic light to cycle from red to green twice before moving through an intersection. Cars and trucks actually moved pretty smoothly on I-4, at the time. It was completed in 1965. Nonetheless, the expressway authority was put in charge of making the beltway happen.

At the time, the agency was planning its first two toll roads, the Bee Line Expressway, now known as SR 528 or the Beachline Expressway, and the initial portion of SR 408, known then as the East-West Expressway. The Bee Line would link Orlando with Brevard County and its nascent space industry. The East-West would connect downtown with a young defense technology sector and the newly created Florida Technical University (FTU) — now the University of Central Florida — in east Orange County.

Regional leaders such as Martin Andersen, then the powerful owner and publisher of the Orlando Sentinel, prominent banker Billy Dial and Orlando Mayor Bob Carr put their faith in the novice agency because they had, in part, little choice. Outside of the I-4 work, Orlando was too small to garner the necessary support in

Washington, D.C. and Tallahassee to win the federal and state funding needed to build major highways capable of carrying large volumes of fast-moving traffic. They were convinced more expressways and, eventually, an entire beltway were needed because they were certain greater Orlando was on the verge of enormous, unprecedented growth. Without a bigger and better-connected road network, these community leaders knew that budding employment and educational

14

Gas Was 27 Cents a Gallon

15 Life magazine, Oct. 15, 1971, issue from the

collection of Joy Wallace Dickinson

Photo courtesy of FloridaMemory.com

From left to right: Walt Disney, Governor W. Hayden Burns, and Orlando Sentinel owner/ publisher Martin Andersen.

centers such as the Martin Company (now Lockheed Martin) and FTU might stagnate rather than flourish.

Another reason: Multitudes of tourists, assorted workers and new residents were being drawn to the area by the Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World, which was announced in 1965 and was under construction and nearing completion. It opened in 1971, triggering a real estate development surge that now has the region’s fulltime population topping 2.5 million — a more than eightfold increase in year-round residents. Some 75 million tourists visit Orlando each year, going not only to Disney, but also Universal Studios Florida, Sea World, a host of smaller attractions and the Orange County Convention Center, now the second largest in the country. That makes Orlando one of the most-visited cities in the country. Walt Disney himself was keenly aware of how important roads were to the success of any endeavor, much less one as ambitious as his budding Central Florida theme park — which he envisioned as a bigger, better version of the Disneyland attraction he had opened during 1955 in Anaheim, Calif.

In a film clip recorded during the mid-1960s, he talked about his pending creation, saying, pointer in hand, “the important thing is that the Disney World is located just a few miles from the crossing point of Interstate 4 and the Sunshine State Parkway (now called Florida’s Turnpike).”

Video of Walt Disney

He also said he liked the park’s location near the center of the state, not to mention the 27,000 acres of largely undeveloped land his company secretly purchased for the park he was building that would forever change life in Metro Orlando. Disneyland’s growth potential in Southern California had been hampered because it was hemmed in by development all around it.

Walt Disney, who died in 1966, might never have envisioned the Wekiva Parkway. Nor might he have foreseen what one day would become the more than 120-mile-long beltway around Orlando owned and operated by CFX, FDOT and Florida’s Turnpike, which operates the state’s extensive toll-road network. But his Magic Kingdom and its assorted offspring certainly are and will continue to be served by the roads.

One of the many roles of the Wekiva Parkway, after all, is providing what some refer to as an alternate, or back door, entrance to Disney World for those driving from the East Coast, via I-95 and I-4. That means the road brings them to the attraction from the northwest — which affords motorists the option of avoiding the often-congested I-4 corridor through downtown Orlando that ushers motorists to the main entrances of the parks from the southeast.

Spreading out traffic is important to the operations of Disney World, which has grown from the Magic Kingdom to include three other major theme parks, a massive shopping, dining and entertainment district and a plethora of hotels.

Facts about the construction of the Wekiva Parkway: Did You Know?

The Magic Kingdom opened in 1971, triggering a real estate development surge that now has the region’s full-time population topping 2.5 million – a more than eight-fold increase in year-round residents.

Just as importantly, the Wekiva Parkway also acts as a regional connector for non-Disney visitors, relieving US 441, SR 46 and other area roads of traffic congestion resulting from growth and ever-increasing east-west travel between northern Orange, south Lake and west Seminole counties.

• Excavated 3.6 million cubic yards of soil to prepare for the road.

3.6M

• Built 8.4 million cubic yards of embankment to support the Parkway. That’s enough dirt to fill 40 cruise ships. 40

• Some 40 miles of foundation piles also were driven to gird 40 bridges and 58 lane miles of road.

• Landscapers planted 440,000 square yards of seed and mulch… …along with laying 2.3 million square yards of sod. That is enough to cover more than 400 football fields.

400

16

17

Workers employing the “top down” construction method on a deck of the bridge over the Wekiva River.

The 1980s Had It All: Star Wars, Conventioneers, Christmas Freeze and Bonds

4chapter 19 18

The Orange County Convention Center opened with 150,000 square feet. Now it covers 2 million square feet. iStock photo.

The 1980s Had it All: Star Wars, Conventioneers, Christmas Freeze and Bonds

The 1980s Changed the Central Florida Landscape

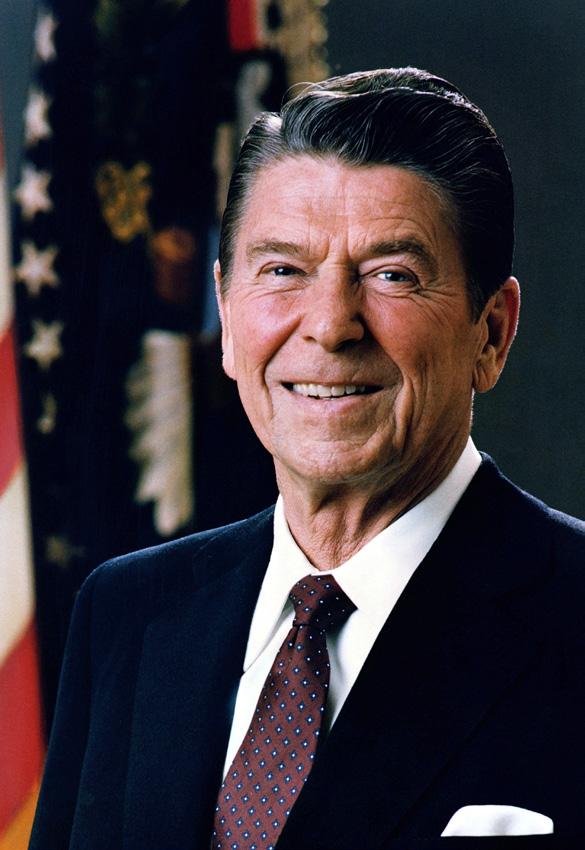

For history buffs, one of the biggest events of 1983 occurred when then-President Ronald Reagan announced a new military defense initiative that was almost immediately dubbed Star Wars, after the popular movie series. The idea behind the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) was to create a high-tech shield in outer space that would prevent missile attacks from hostile nations, specifically the then-Soviet Union.

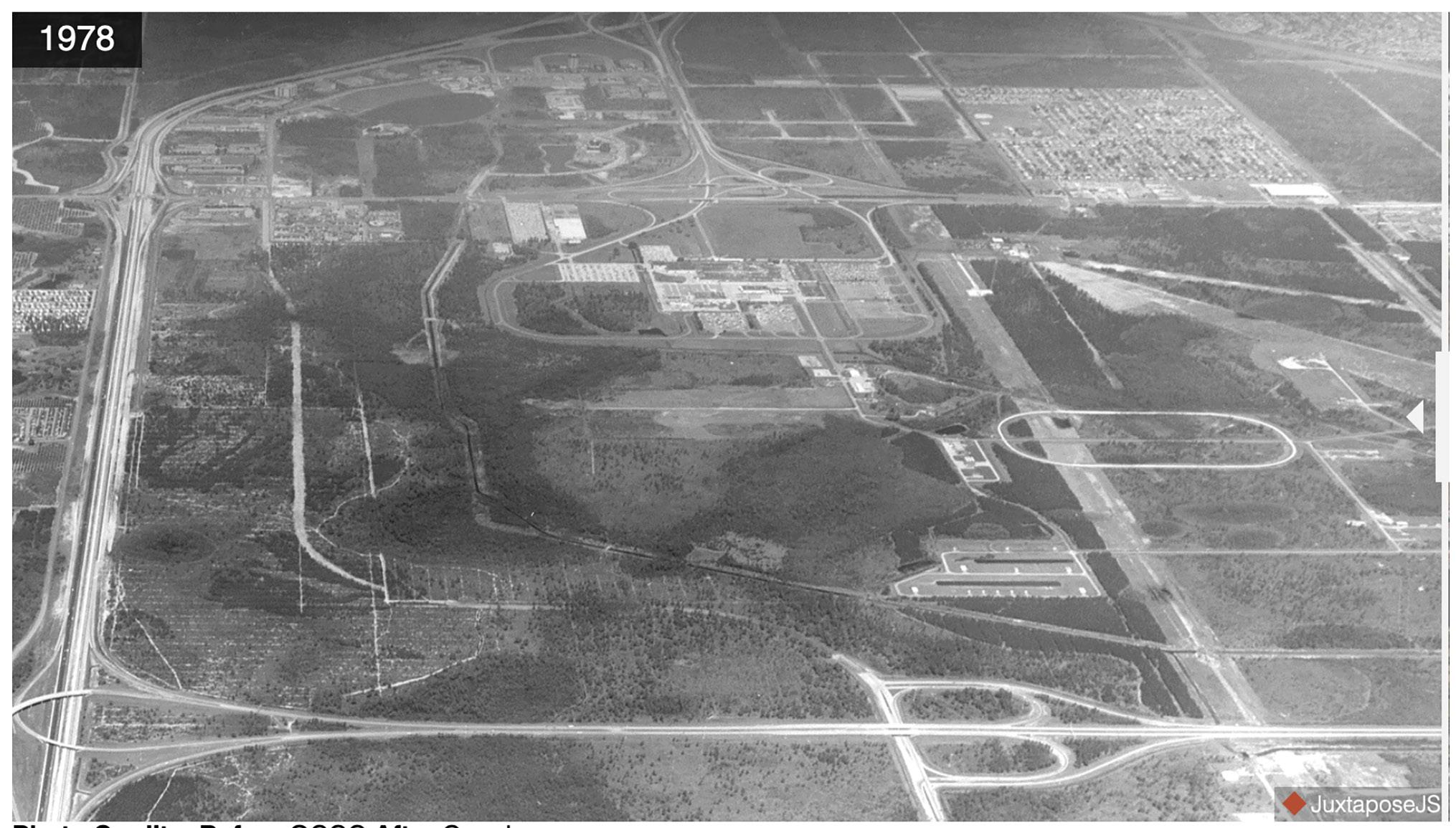

Closer to home, gas was selling for 90 cents a gallon during 1983 — which, in retrospect, was a pivotal year in Central Florida because the fledgling Orange County Convention Center first opened its doors and a harsh cold snap swept in from northern climes on Christmas Eve. The brutal arctic-like air dropped temperatures 30 degrees in a less than two hours, falling below 20 degrees for hours in some locations. This devastated Florida’s citrus crop, maiming orange trees on some 120,000 acres and costing the industry nearly $1 billion in damages and lost income.

The convention center, with its 150,000 square feet of exhibition space, opened 10 months earlier and was hailed as the beginning step in the area’s bid to winning a share of the growing national convention and meeting market. The center was just a few miles from both the recently opened international airport (1981) and the Bee Line Expressway, making it easily accessible for would-be conventioneers, whether local or from out of town. The center has since expanded to 7 million square feet, making it the secondlargest convention complex in the country.

The 1983 killer freeze, meanwhile, triggered the eventual demise of the once-thriving citrus industry in the region, hastening in a period of new housing replacing dead and dying orange trees, opening up hundreds of thousands of acres for real estate development. Among the large developments that have since sprung up in old groves are Horizon West and Stoneybrook West in west Orange County.

20

21

clockwise, upper left: Frozen oranges from kocoweatherblog. wordpress.com. Convention site from 1978 and 2018 from the OCCC.net. President Reagan from Wikipedia. Orlando International Airport control tower photo by Jerry Driendly/Getty Images. Frozen orange tree photo from Florida Dept. of Agriculture and Consumer Services - Division of Plant Industry.

Photo credits

To help serve those communities and other budding subdivisions and commercial development, the expressway authority in the year 2000 opened SR 429, a 10.6-mile section from Florida’s Turnpike in Ocoee to US 441 in Apopka. It featured the highest flyover ramp in Central Florida, at almost 200 feet above sea level.

The road now extends nearly 23 miles from US 441 in Apopka south to I-4 in Osceola County. That provides west Orange and Osceola counties with an alternate northsouth route to I-4. It also hooks up with CFX’s portion of the Wekiva Parkway, just to the north of Apopka.

But back in 1983, such roads were little more than sketches on a proposed map, though steps were about to be taken that would move those blueprints from the realm of “want to” to “can do.”

It happened at the authority offices, then ensconced in the old Metropolitan Life Insurance building, a cramped single-story structure directly beneath the East-West on the south end of downtown Orlando, by Lake Lucerne. Expressway authority consultants and officials, including then-board Chairman Phil Reece, had gathered to talk about bonds, the exact date and time a bit uncertain due to the passage of time.

What Reece and company agreed to do in that initial meeting was to address public finance policies that would allow greater flexibility in what money raised from the sale of bonds could pay for in a toll road system. That session laid the foundation for a decision two years later that had a profound effect on both the agency and the entire road network of Central Florida.

At the time, the East West and the Bee Line expressways had proved to be immensely popular with tollpaying drivers. In fact, the roads were generating revenues well in excess of what was needed to fulfill the repayment requirements of the bonds. According to the bond covenants in place then, all tolls the expressway authority collected from those roads had to be used to pay off those specific debts and maintain the roads, or be placed in a reserve account. That was essentially it. The official term is project-specific bonds.

Reece knew even then that what the organization (OOCEA) accomplished with the new bond covenants was a big deal. “We saw what the potential was. We could get things done because we were so small.”

So they began the arduous task of redefining the future bond rules to allow excess money — that is, funds above and beyond the debt payments, maintenance and reserve accounts — to be used to pay for new toll roads as long as they were part of the agency’s overall system.

Reece said the expressway authority officials, including then-Executive Director Bill Gwynn and bond consultant Keith Denton, had been watching some toll road authorities across the nation doing just that type of bond refinancing. So they figured the timing was right.

By 1985, the expressway authority board voted unanimously to modify the bond structure and refinanced the existing bonds to reflect those alterations. Instead of being project-specific, the bonds were now system-specific, meaning the money raised through tolls could support all the expressway authority roads, including future ones, not just the two in existence.

CHANGE AHEAD

One of the reasons for working first on the eastern part of the beltway, Reece said, was because of strong opposition from conservationists at that time to building a road through the Wekiva River Basin. Environmentalists also had been fighting the expressway authority for years on a variety of other road issues. Reece, for one, was not up for what he anticipated to be another pitched battle over how parts of the western beltway and the Wekiva Parkway would affect the environment. Why engage, he said, in what could be protracted disagreements when there were other roads that needed to be built without as much dissent from conservationists and other opponents?

But Reece said the expressway authority — which had a full-time staff of eight back then — knew more roads had to be built, most prominently the beltway, including the Wekiva Parkway. And since new roads rarely pay for themselves at first, the expressway authority needed the extra cash provided by the East West and Bee Line to jump-start and finance its future projects.

During that same year —1985—the authority board passed a resolution promising to protect the Wekiva River if the expressway authority ever built a road in the area.

The bond modifications led to a construction boom, starting with the eastern side of the beltway, or SR 417. The northern portion of SR 417 ran from SR 535 to the Seminole County line, where FDOT assumed responsibility for the road and extended it to US Highway 17/92 in Sanford. The expressway authority began work on its leg first, with the southern segment to Orlando International Airport following behind.

Reece knew even then that what the organization accomplished with the new bond covenants was a big deal. “We saw what the potential was,” recalled Reece, now a retired pool builder. “We could get things done because we were so small.”

Another plus to going east was the projected ridership and revenue numbers. Those studies predicted much stronger usage to the east due to the expansions of the Orlando Internationl Airport and the Orlando/Orange County Convention Center to serve an ever-increasing number of tourists and conventioneers.

After opening in 1998, SR 417 would play a vital role in the growth of several communities along its route, including Meadow Woods, Hunter’s Creek, Southchase and Lake Nona, a large-scale master-plan community with a concentration of health and hospital facilities and plans for upwards of 30,000 residents and the creation of 30,000 jobs.

Reece and expressway authority officials had no way of foreseeing such large-scale growth or monetary impact, but they were certain the road would spur some development.

“Let’s just move on,” Reece said was the feeling of agency board members at the time they approved SR 417. “Let’s do the next one.”

22

23

Phil Reece

Video of Phil Reece

chapter

A Long Time Coming: The Beltway Begins During the 1990s

25

of

Corp. of

Inc. 24

A backhoe drives pilings for the bridge over the Wekiva River. Photo courtesy

Quest

America,

5

A Long Time Coming: The Beltway Begins During the 1990s

First Leg Was SR 417, Also Known as the GreeneWay

Work on SR 417 began during the early 1990s in conjunction with FDOT. It was named the GreeneWay after the late James B. Greene, who was the agency chairman from 1971 to 1985. The expressway authority was responsible for the first 22 miles, which opened in1998. Later improvements, such as updated interchanges, have allowed it to handle additional capacity today.

The expressway authority started construction on the middle section of the western leg of the beltway in 1998, with the almost 11-mile segment opening two years later. Running from Apopka to Ocoee, the leg was named after longtime

Central Florida elected official Daniel Webster. It featured the expressway authority’s first “open-road tolling” system for travelers using E-PASS and other accepted electronic transponders. Under the new design, E-PASS customers paid tolls automatically as their vehicles passed under electronic sensing gantries on the expressway — now a common practice on the CFX road network.

The innovation offered a time-saving alternative to stopping at a toll plaza and plunking down quarters in a basket or paying with bills and seeking change from an attendant.

The expressway authority stayed busy between 2003 and

2013, starting and completing State Roads 414, 451 and 551. Combined, that is more than 29 miles of road.

SR 414, which was named after John Land, the late, longserving mayor of Apopka, took six years to complete, in part because of funding issues related to the recession that hit the year construction began.

When the entire road was opened Jan. 18, 2013, Max Crumit, the expressway authority executive director at the time, quipped “Some people thought it would be a cold day in….before we finished this road.” The weather was cool, overcast and windy.

26 27

Test piling preparation on westbound side of Wekiva River bridge. Photo courtesy of Quest.

SR 451 also serves Apopka. At 1.9-miles long, it opened in 2013 and connects State Roads 414 and 429 north to US 441. This road is well traveled by commuters in northwest Seminole County and northeast Orange County.

On the other side of Orange County — or to the east in one of the fastest-growing areas at the time — is SR 551, also known as the Goldenrod Road Extension. Opened in March 2003, it runs 2.7 miles from Goldenrod Road at Narcoossee Road south to Cargo Road. The well-travelled road connects Goldenrod Road to SR 528, east of the Orlando International Airport.

SR 551 is an example of regional cooperation involving four agencies that came together to finance the $38 million project. The expressway authority served as the lead agency with its partners, the Greater Orlando Aviation Authority, the city of Orlando and Orange County. The road is being repaid through toll revenues generated solely by the extension.

But the Wekiva Parkway remained largely moribund as other projects took off — and even as SR 429 was completed. In fact, the Wekiva Parkway at one point dropped off the list of potential road projects for the region by MetroPlan Orlando, which sets transportation policy for Orlando, Orange, Seminole and Osceola counties. MetroPlan officials deemed the road too expensive and potentially injurious to the environment. That did not dissuade Allan Keen, a Winter Park developer who was appointed by Gov. Jeb Bush to the expressway board in 2002, when Hal Worrall was the executive director. At the time, FDOT and the expressway authority also were pursuing other projects that likely would ensure the Wekiva Parkway would never be built. For instance, FDOT District 5 was going to widen SR 46, while the agency was planning to leave the northern end of the western beltway just where it was, at US 441 near Apopka.

Mike Snyder, then the FDOT District 5 secretary, got together with Keen to talk about the separate, timeconsuming and expensive projects their respective agencies were pursuing. They decided it did not make sense to go their own ways when they conceivably could collaborate on only one option, the Wekiva Parkway.

“We had a gentleman’s agreement,” said Snyder, who would become the executive director of the expressway authority in 2004, replacing Worrall.

About that same time, Charles Lee, Audubon Florida’s director of advocacy, and other conservationists had come to the conclusion that the Wekiva Parkway — if built correctly — would better protect the Wekiva River Basin than a wider SR 46 and truncated western beltway.

So Lee and several other environmental supporters asked to meet with Keen and Snyder. They got together in FDOT’s regional headquarters in DeLand.

“Could we pause and see if we could find common ground,” Keen remembered Lee asking the pair. “We said, ‘yes.’ We promised we would give them input and it wouldn’t happen without their input.”

Lee said he was particularly concerned then about black bears because the Wekiva River Basin supports one of only five remaining black bear populations in Florida.

In 1994, SR 46 was the first corridor in the state to get an underpass specifically designed to save bears because so many of the animals had died from being struck by cars. The six-mile stretch of SR 46 in Lake County ranked far above other roadways, accounting for about 41 bear deaths between 1976 and 1999, according to state statistics. (Those are the most recent available numbers.)

“It was the most pernicious bear-killing road in the state,” Lee said. “We were facing the reality that the outcome (widening SR 46) would be much worse (than the Wekiva Parkway).”

29 28

Allan Keen

Mike Snyder

Video of Mike Snyder

Video of Allan Keen

Widening the road could easily have led to even more collisions between cars, trucks and bears, as well as assorted other wildlife, Lee said.

With Audubon Florida, the Sierra Club and other conservation groups like the Florida Wildlife Corridor and Friends of the Wekiva voicing support, Keen’s next step was to contact then-Gov. Bush. Getting Bush to back the project was important, Keen figured, because the road would be constructed through three different counties, Orange, Seminole and Lake. The expressway authority only had the ability to build in Orange and Orlando at the time.

Either the state would have to get involved, Keen figured, or the expressway authority would have to seek legally binding permission from the other counties to work in their jurisdictions. That promised to be a timeconsuming exercise. Keen was able to arrange an in-person meeting with Bush in Tallahassee to discuss the Wekiva Parkway. Bush readily agreed to help, Keen said.

“The governor was very interested in seeing the expressway authority thrive, not just survive, but thrive,” Keen said. “It was not a hard discussion or process.” Without Bush being on board, Keen said, “It may not have happened, or it would have been a much slower process.”

But even with the aid of Bush, the aspiring Wekiva Parkway builders had to come up with ways to overcome the obstacle Reece outlined 20 years earlier: Mitigating the damage that could be caused by crossing the fragile Wekiva River with a major highway.

And, if built, there were financial considerations, too. The Wekiva Parkway undoubtedly would become the most expensive road ever constructed in Central Florida— not to mention that homes and businesses along SR 46 likely would have to be condemned and razed for construction. (The expansion of I-4 through downtown Orlando has since supplanted the Wekiva Parkway as the costliest road project in the region, checking in at more than $2.4 billion.)

“If you were weak of mind and spirit, you would say, ‘This isn’t going to work,’” said Keen, who spent nearly seven years on the expressway authority board, including two as chairman.

But Keen was undaunted by the Wekiva Parkway’s potential barriers. He focused on the road being the most rational step for the region because it would complete the beltway.

“It was simple in its logic,” Keen said. “The political fortitude just hadn’t been there.”

As important as Bush was to the Wekiva Parkway, the key to getting the road built, all involved agreed, was winning the support of the environmental community. “We developed a trust more than anything else. They believed that what we said we were going to do,” Snyder said. Keen added that he and Snyder had concluded that protecting the river and basin would become the overarching goal of the project. “We’re not going to blow through and destroy it,” Keen said.

Once the decision was made to move forward, Keen said, “They (environmentalists) took a really high-level public-good philosophy and took it forward.”

Nancy Prine, an ecological champion for more than 30 years and a board member of the Friends of the Wekiva, said the accommodations the expressway authority and FDOT made to protect the basin are “a tremendous thing for the environment.”

The governor was very interested in seeing the expressway authority thrive, not just survive, but thrive. – Allan Keen

30 31

A kayaker enjoying the Wekiva River.

Governor Bush Gets Serious About the Wekiva Parkway

6

chapter 33 32

Rough drafts of potential bridge designs overlaid over the old bridge that spanned the Wekiva River.

Governor Bush Gets Serious About the Wekiva Parkway

Creates Commission to Set Alignment in 2003

The governor initially put together a commission in early 2003 to propose a pathway for the Wekiva Parkway, a critical step in the design and construction of any road. That was the year the United States invaded Iraq, the space shuttle Columbia disintegrated upon its return from space, killing seven astronauts, and Erika Dunlap of University of Central Florida was named Miss America. Gas checked in at a $1.59 a gallon.

The initial alignment recommendations of the commission were not greeted warmly. They were considered too general by many involved in the planning, which elevated concerns about possible harm to the Wekiva River Basin rather than alleviating them, said former state Sen. Lee Constantine,

now a Seminole County commissioner.

A second panel — the Wekiva River Basin Commission — was appointed by Bush in late 2003. The new group had 28 members and was run by Constantine, whose Senate district included a large chunk of Seminole County.

The commission had representatives from the environmental protection community, local and state governments and adjoining neighborhoods. The idea, Constantine said, was to “get everyone involved.”

After hundreds of hours of meetings, the commission came up with 17 optional corridors, ranging from an alignment that spared most homes and businesses to placement of interchanges to what lands to purchase to limit

development. The final vote was 27-1 in favor of the package.

The report was forwarded to the state Legislature, which adopted it unanimously in both houses — a rare event for rules so complicated and potentially controversial. It was named the Wekiva Parkway and Protection Act (Chapter 369, Part III, F.S.).

One of the panel’s recommendations was a stipulation that the commission would monitor construction until it was complete. As of 2023, the panel still meets three to four times a year, often at a small conference center at Wekiva State Park or at Wekiva Island along the river. The goal of the board is to ensure the road is built to the law’s specifications.

“We knew it would be a long project, but who knew it would be this long?” Constantine said.

An elected public official for more than 40 years, Constantine said he considers the Wekiva Parkway and Protection Act one of his most significant achievements while in office. He started out in 1978 with his election to the Altamonte Springs City Council Commission, then served as Altamonte Springs mayor, a state representative, a state senator and Seminole County commissioner.

The Wekiva River and its basin, he said, is a picturesque, vital natural resource that must be protected.

Brenda Carey, who became the first female chairman of the expressway authority in 2019, was also a member of the Wekiva panel. She admits there were times when she wondered if the Wekiva Parkway would ever be built, especially after it was eliminated from the list of potential road projects of MetroPlan, the region’s transportation planning agency.

But, she said, all the planning and machinations became worthwhile once the road finally started taking shape.

“It will truly help us in Seminole County with the flow of traffic, particularly on I-4. The congestion should get better,” said Carey, who was a Seminole County commissioner for 16 years before retiring from politics in 2020.

34

35

Video of Lee Constantine

Lee Constantine

Early hand-drawn sketches of the bridge showing possibilities and themes.

Early 2000s: Neighbors Learn the Wekiva Parkway Really Is Going to be Built

7

chapter 36 Traveling forms were among the innovative construction techniques employed during the construction of the bridge over the Wekiva River. 37

Early 2000s: Neighbors Learn the Wekiva Parkway Really Is Going to be Built

Skepticism Greets News

Once the Wekiva Parkway and Protection Act was passed in 2004, the expressway authority began a major push to inform area residents and businesses about what would happen, where, when and why. The public information effort was headed by Mary Brooks, lead public outreach consultant.

Brooks set about contacting some 30,000 property owners within the initially wide potential path of the planned Wekiva Parkway. She was met with a fair bit of skepticism 19 years ago.

“Residents were really concerned that the way of life that they had known — that their families had known for generations — was really at risk,” Brooks recalled.

Brooks said she made a concerted effort to run a “robust” outreach campaign that would keep people in the know about what was going on. Over time, she began to develop relationships with many of those living and working in the area.

Slowly, opinions began to turn from negative to positive, she said, when people realized she would return their phone calls and answer their questions, even when what she had to

say was not necessarily what they wanted to hear.

Starting in 2005 — when the expressway authority started the Wekiva Parkway Project Development & Environment study — through the end of 2019, Brooks oversaw some 900 public workshops, community meetings and outreach engagements, attracting nearly 20,000 people.

“We had many people who went, ‘Hell no, we won’t go. Over my dead body. Over my cold dead hands will you wrench this property from me,’ to ‘When’s it going to open? When can I get on? How much is it going to cost me?’ ”

Brooks said.

Especially helpful, she said, was the fact that when the first two Wekiva Parkway segments opened, some long-standing traffic tie-ups in the area dissipated because the new sections offered better travel options to motorists than the narrow, often-crowded streets they had been using for decades.

Video of Mary Brooks

38

39

Mary Brooks, vice president of Quest Corp. of American, Inc., is in charge of public information for the Wekiva Parkway.

While Brooks was doing her best to spread the word about the project, years would go by before any dirt was disturbed. A variety of factors came into play.

First off, Allan Keen, Mike Snyder and the agency staff began the hard, unglamorous work of getting numerous planning and design studies underway, seeking environmental approvals from various government agencies, and putting together a financing proposal. They also decided to run the project through federal environmental protocols, a painstaking process that would pay a large dividend a few years later.

The economy was uneven during that time, too, including a major recession starting during late 2007 that decimated the stock market, as well as home sales and values. Unemployment spiked nationwide and in Central Florida, dropping ridership and revenues on the expressway authority roads. That reduced toll income made an expensive proposition like the Wekiva Parkway more difficult to finance. Interest in building the road also cooled on the part of FDOT, which was dealing with budget cuts imposed by the governor and a state Legislature struggling to balance its spending ledgers during the recession.

Reacting to the seeming indifference of FDOT, the expressway authority officials began to discuss ways of constructing the Wekiva Parkway solo. That included talks about raising additional money through higher tolls, which had not been increased since 1990. (The agency actually lowered them at two plazas in 1992.)

“We had tried forever to get the FDOT engaged in the Wekiva because it was so important in our minds,” Snyder said. “From a business point of view, it may not have been the smartest thing to do (raise tolls), but from a transportation point of view it was critical.”

A 25-cent increase took effect during April 2009.

“There’s no free lunch when it comes to roads,” said Rich Crotty, then-chairman of the expressway authority board. Crotty, who was the mayor of Orange County at the time, had replaced Keen as chairman.

Higher tolls, Crotty said, would lead to the eventual completion of the beltway around Orlando and, just as importantly, solidify the expressway authority’s monetary outlook. That would have the added benefit of preventing the expressway authority from paying more interest on almost $1 billion worth of variable-rate bonds it had sold previously to build roads. Interest rates the agency was paying at the time could have increased because of the temporary drop in ridership caused by the Great Recession.

The Wekiva Parkway planning continued for the next few years as the finances of both the expressway authority and FDOT slowly recovered, along with the state and national economy. A major breakthrough came during a weekend in December 2011, when Snyder and FDOT officials, including then FDOT Secretary Ananth Prasad, reached an unofficial accord: The expressway authority would build and own about 10 miles in Orange County and a piece in Lake County, while the state would be responsible for the remaining 15 miles.

One of the linchpins of the arrangement was CFX’s tentative agreement to repay nearly $240 million it owed FDOT during the course of the next 12 years. Starting in 1964, FDOT had been lending the expressway authority between $8 million and $10 million annually for operating and maintaining some tollbooths and portions of toll roads owned by the state. The borrowed state money also enhanced the expressway authority’s standing with bond buyers, which was especially important during the agency’s early years, when it was still establishing its creditworthiness with the bond market. (CFX paid off the debt early in 2016.)

“It (the Wekiva agreement with FDOT) was in a pretty good position,” was Snyder’s summation of the deal when he retired at the end of 2011.

Walter Ketcham, an Orlando attorney who served on the expressway authority board from 2009 to 2015, said Snyder was the driving force behind the Wekiva Parkway, keeping the project alive by continuing studies and

planning even when the project had little backing.

Getting FDOT to negotiate and agree with the expressway authority on building the Wekiva Parkway together was critical, Ketcham said. Then board member and Orange County Mayor Teresa Jacobs — who replaced Crotty in 2011 — pushed hard for FDOT involvement, too. Jacobs, now chair of the Orange County School Board, had formerly worked at FDOT.

Said Ketcham: “We could have done it (built the Wekiva Parkway), but it was potentially going to cost us a lot of money. It’s like if you buy an expensive car or house. You can afford it, but doing that will mean you have to do without a lot of other things.”

Max Crumit, who replaced Snyder as executive director, said the basics of the agreement were in place when he took the top job at the expressway authority. But he conceded getting the final signatures was not easy because there was one big hitch remaining: FDOT wanted approval over all future expressway authority financial commitments. The expressway authority balked at that requirement.

41

The old bridge was removed and a service bridge was opened (left) to handle traffic while the new bridge was under construction, during December, 2020.

40

Road sections were elevated to allow wildlife to cross underneath, just west of the Wekiva River, during December, 2020.

Orlando Senator Swings for the Fences

Enter Andy Gardiner, an Orlando Republican and then the Florida Senate majority leader. He was tired of hearing about seemingly nonstop Wekiva Parkway talks and wanted to witness some action, as in the actual digging of soil and pouring of asphalt.

Legislature was in session during the winter of 2012 calling for FDOT to build the entire road, with the expressway authority chipping in $50 million annually for 35 years to pay for building the Wekiva Parkway. The bill died during the session.

expressway authority. “We have bond holders,” he said. “We couldn’t give money away.”

Transportation Builders Association in Tallahassee, said Gardiner’s gambit certainly grabbed everyone’s attention.

Prasad said. “He was putting ideas on the table to jump-start the conversation.”

expressway authority to pay the state was essentially a negotiating ploy. He wanted them to come to their own agreement by offering them one that he figured neither agency would particularly like.

Crumit and Prasad to a conference room within the chambers of his Tallahassee Senate office.

enough,” Gardiner said. “It needed to get done.”

A baseball fan and former high school pitcher, Gardiner always kept an aged Louisville Slugger bat in his office. As much to lighten the atmosphere as to make a point, Gardiner sauntered into the meeting carrying the 32-ounce piece of wood.

“I was hitting my hand with it. I walked around a little, did my Robert De Niro bit,”

He told Crumit and Prasad that they had

Crumit remembers Gardiner saying, “You can either have a deal when you come out of this room, or you can face number two. And you

Prasad and Crumit took Gardiner’s direction seriously. Each made concessions: FDOT would drop its demand to oversee the agency’s future

Crumit and Prasad shook hands after a couple of hours of negotiations and had an agreement.

Ketcham characterized the pact as “a great deal. It

That same year, the expressway authority also received a much-coveted finding from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) that the road would not have “any significant impact upon the environment.” That conclusion was based on all the environmental studies that the expressway authority

The decision was significant because it cleared the way for the expressway authority to snag a low-interest loan from the federal government three years later, which was ultimately secured and would significantly speed construction of the Wekiva Parkway, allowing

42

43

Max Crumit, former CFX Executive Director. Andy Gardiner, former Florida Senate Majority Leader.

Video of Max Crumit

Video of Andy Gardiner

Central Florida Expressway Authority Created to Build Roads Throughout Region

8

chapter 44 45

Temporary barriers were placed along the Wekiva River to prevent erosion from seeping into the water.

Central Florida Expressway Authority Created to Build Roads Throughout Region

“A Very Good Thing for Transportation” — Walter

Ketcham, former expressway authority chairman

By 2014, the start of construction on the agency’s first leg of the Wekiva Parkway was a year away. But major change had come to the agency.

The state Legislature created a new role for OOCEA, renaming it the Central Florida Expressway Authority (CFX). This change strengthened the expressway authority’s position as a world-class regional mobility network that incorporated multimodal corridors and intermodal facilities within its right-of-way. CFX also was empowered to build roads not just in Orlando and Orange County, but also in Seminole, Lake and Osceola counties. Brevard County joined the organization in 2017.

Then-Lake County Commissioner Welton Cadwell was elected the first chairman of the CFX with its expanded jurisdiction and duties. He predicted there would be people who doubted the effectiveness of the expressway authority.

“We know you’re out there,” he said. “We’re going to prove you wrong. We’re going to be a dynamic board.”

Added then-state Sen. David Simmons, R-Altamonte Springs, a sponsor of the bill that regionalized the agency:

“Wipe the slate clean and start with a new beginning.”

Simmons said he envisioned the agency solving transportation problems throughout the region and not just Orlando and Orange County, arguing that roads do not end at jurisdictional lines, but invariably cross them.

Ketcham, for one, initially questioned the change.

He worried the board would be too big, leading to poor decisions. “I wasn’t sure what to expect,” he said. “But it was very good. It brought in new blood. In the long run, it became a very good thing for transportation.”

Former Seminole County Commissioner Brenda Carey, who joined the new board as the Seminole County representative, said expanding the responsibilities of the agency just made sense. “I think the process we use is very good,” she said. “It’s one we can use for all major regional roads.”

46

47

Walter Ketcham, former expressway authority chairman.

Video of Walter Ketcham

While one of the new organization’s top priorities was getting the Wekiva Parkway built, it almost immediately faced a new obstacle. A parcel of land in the Wekiva Basin unexpectedly came up for sale, but the CFX did not have the money to buy it, nor did FDOT.

In stepped Scott Taylor, a Audubon Florida member who lives in the area, and Garry Jones, president of Full Sail University in Orlando. They went to an auction and bought the land, which had been slated for a commercial and residential development project that fell apart. Rather than take the chance that the plan might be revived, and construction restarted, Taylor and Jones paid $467,500 for the property for conservation.

“Our objective was to keep it out of the hands of someone who might develop it,” Taylor said. “We wanted to send a message that a private/public partnership could work. And we did.”

Taylor and Jones later sold the land to the state for $450,000, taking a small loss on the deal.

The Wekiva Parkway is a success, Taylor said, because development was kept to a minimum. He pointed out the state and CFX bought 3,400 acres in the area and designated them for conservation.

He rates the environmental efforts of CFX and the state as a 10 out of 10 for the Wekiva Parkway. “They are following through on what was supposed to happen,” said Taylor, who still monitors progress on the road by attending Wekiva Basin Committee meetings.

“The idea is to make sure nothing goes south…that they are doing it in the way it was intended to be done,” Taylor said. “I’m really happy with the way it is turning out.”