14 minute read

Holocaust survivor Michael Bazyler champions restitution for those whose legacies were looted

JUSTICE STOLEN

Advertisement

Twenty years aft er World War II ended, the shadow of atrocity still shrouded the young life of Michael Bazyler. Th e son of Polish and Russian Holocaust survivors who as teenagers fl ed the Nazis to Uzbekistan, Bazyler was 11 when his family immigrated to the United States as political refugees.

For a spirited youngster starting over in a foreign land, the grip of history squeezed a bit too tightly.

Th e Holocaust was “something I tried to stay away from when I was growing up,” Bazyler says. “It was like the air you breathe. When I saw someone with a tattoo on their arm, it was like everyone had one.”

Over time, however, Bazyler came to embrace his connections to family and community. He found that the more he sought to apply his talents for persuasion, research and scholarship, the more he was drawn to international human rights law. As he saw new examples of genocide and mass theft in places like Rwanda, Syria and Iraq, how could he not take up the challenge of so much unfi nished work? In the 1990s, Bazyler began researching and writing about the mass theft of Jewish property in Nazi-occupied Europe. He also became vice president of Th e 1939 Society, an organization of Holocaust survivors, their children and supporters that promotes Holocaust education in partnership with the Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education at Chapman.

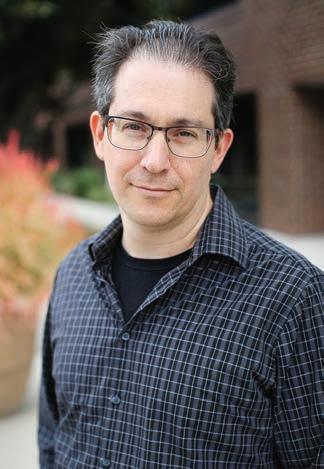

Th ese days, Bazyler, JD, is a professor at Chapman’s Fowler School of Law who has testifi ed before Congress on Holocaust restitution and has had his work cited by the U.S. Supreme Court. His book “Holocaust, Genocide, and the Law” won the National Jewish Book Award, and his new work, “Searching for Justice Aft er the Holocaust,” chronicles a comprehensive research project he led, examining legislation passed by the 47 endorsing states of the 2009 Terezin Declaration on Holocaust Era Assets and Related Issues. Th e research project was commissioned by the European Shoah Legacy Institute and was presented in 2018 to the European Union.

BY DENNIS ARP PHOTOS BY JUSTIN SWINDLE

Th e son of Holocaust survivors, law professor Michael Bazyler champions restitution for those whose legacies were looted.

Professor Michael Bazyler inspires young advocates such as Jade Stocks (JD ‘19), left, and Kaylee K. Sauvey (JD ‘18) to seek justice for victims of genocidal regimes. “I think it’s a goal of anyone who pursues higher education to try to make positive change in the world,” Sauvey says.

Bazyler’s scholarship reveals that a signifi cant amount of the property stolen during the Holocaust has yet to be returned to its rightful owners, who are seeing the clock tick away on their chances for justice. Estimates are that almost half of the 200,000 remaining Holocaust survivors live in poverty.

Evidence of the need for Bazyler’s research is all around. Recent news reports detail a high-profi le case in which a Southern California federal judge allowed a Spanish museum to keep a $30 million Camille Pissarro painting looted by the Nazis, prolonging the 20-year bid for restitution by heirs of the Jewish woman originally victimized by the theft . Bazyler fi led an amicus brief in the case.

“Here we are 70 years later, and it’s astounding that these cases are not being resolved,” Bazyler says. “I always preface remarks about restitution by saying that the Holocaust was not about money or property – the Jews were not murdered because they had art. But every genocide is not just about mass killing but mass theft . And the Nazis stole mercilessly from the Jews of Europe.” Th e precedent set by the case has helped other genocide victims achieve justice. One case involved an Austrian Jewish emigre living in California who sought return of fi ve Gustav Klimt paintings stolen from her family by the Nazis and subsequently acquired by an Austrian state museum. Th e case became the basis of the 2015 fi lm “Woman in Gold,” starring Helen Mirren and Ryan Reynolds. Aft er years of legal wrangling, the woman, Maria Altmann, ultimately won return of the paintings, valued at tens of millions of dollars.

Th ough such rulings are hard-won and rare, the work continues, encouraging young advocates to fi ght for justice.

Kaylee K. Sauvey (JD ’18) was in her fi rst year at the Fowler School of Law when she took a class with Bazyler, who then recruited her as a research assistant. Even now as she practices probate, trust and estate law, Sauvey does pro bono restitution work. She combs through lists released by the City of Warsaw, showing Holocaust-era properties eligible for restitution. She posts the information to a database maintained by the World Jewish Restitution Organization. “Over the years, almost all were killed or left ,” Stocks says. “It’s important research, from a historical, moral and legal point of view. It raises a lot of questions.”

In addition to legal procedures and research techniques, Bazyler taught Stocks about resolve and resiliency, she says. And she isn’t the only one.

“Professor Bazyler has inspired a lot of people who were probably already interested in social justice but now look at these issues in such a meaningful way that it really deepens that connection,” Stocks says.

Across Bazyler’s 30 years of scholarship and research, the rewards are as voluminous as the dusty archives and case fi les he still scours.

“I tell my students, ‘Look, if you want to go to a big fi rm and make lots of money, that opportunity is there. I started there. But you can also do pro bono work that can make your career as a lawyer so much more satisfying,’” Bazyler says.

“I want my students to be fi ghters for justice.”

Th e Warsaw bureaucracy mechanically follows the letter of Polish law, which says the dispossessed have six months aft er a posting to fi le a claim. But city offi cials actually hope their postings will go unnoticed, Bazyler says

“Th ey want the six months to expire so they can keep the property,” Bazyler laments.

As a Fowler Law student, Sauvey would spend hours in the library, fi lling binders with restitution-related information for follow-up by Bazyler and others.

Perhaps no one knows better than Bazyler the diffi culty of achieving justice in decades-old cases where the trail of property ownership was trampled by regimes exercising untrammeled power. He was co-counsel in the precedentsetting 1990s case “Siderman v. Republic of Argentina,” involving a Jewish businessman who was tortured and had property seized during the “Dirty War” years. Th e case was mired in the Argentine courts when Bazyler and his legal team had a breakthrough. Because Argentina did business in the U.S., Bazyler proved that the U.S. courts had jurisdiction. Just before the case came to trial, it was settled.

“I came to law school fascinated with the subject, and then my professor happened to be this great expert,” Sauvey says. “I think it’s a goal of anyone who pursues higher education to try to make positive change in the world – to seek a measure of justice.”

For Jade Stocks (JD ’19), the catalyst for involvement was a comparative law class taught by Bazyler. She found he was eager to support her research interest in Middle East restitution cases and their connection to foreign policy. Professor and student now share a research interest in a huge Jewish Iraqi archive recovered from Saddam Hussein’s palace during the Iraq War. Th e archive documents a time when Baghdad had a thriving Jewish population.

Opposite page: Art treasures looted by the Nazis during World War II were discovered in salt mines and hidden vaults, but many of the works have yet to be returned to victims or their heirs. In the photos shown here, paintings are examined by a U.S. soldier as well as generals Omar Bradley, George S. Patton and Dwight D. Eisenhower. Photos: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park

DO WE CONTROL OUR ACTIONS?

Chapman’s new Brain Institute pairs neuroscience with philosophy to pursue centuries-old questions of consciousness and free will.

BY DENNIS ARP

It’s a faculty biography on an institutional webpage–typically not a source for gripping prose. But here we find compelling passage into a scientist’s world.

“You experience it to be within your power to stop reading this paragraph.” Stop reading? To the contrary: Lead on, Uri Maoz, Ph.D., psychologist and computational neuroscientist in Crean College of Health and Behavioral Sciences at Chapman University. Maoz is a founding member of Chapman’s new Institute for Interdisciplinary Brain and Behavioral Sciences – the Brain Institute.

“Apparently, you freely decided to continue. Perhaps you are curious how it will unfold.” Yes, curiosity definitely is growing as the intro to Maoz’s profile rolls on.

“But you strongly sense that you could have done otherwise; you could have stopped reading (and you still can).” Welcome to the intriguing domain of Maoz and his Brain Institute colleagues, who seek to expand our understanding at the intersection of decision and action. How does the brain give rise to the conscious mind? Are humans endowed with conscious free will? Do we control our actions, or are we being controlled? Such questions “have an air of importance for our human identity,” says Amir Raz, Ph.D., director of the Brain Institute. Historically, these ponderings and explorations have been ceded to philosophers. The Brain Institute is leveraging the tools of neuroscience, including brain-imaging technology and computational modeling, to design experiments that bridge science and philosophy. The institute’s ambitious research program establishes a new field in the study of the brain – the neurophilosophy of free will. The program is validated by more than $7 million in funding, including $5.34 million from the John Templeton Foundation and $1.55 million from the Fetzer Institute. With an additional $150,000 coming from the Fetzer Memorial Trust, the funding total of $7.04 million represents Chapman’s largest nonfederal research grant to date.

The support puts Chapman at the hub of a global research project involving 17 universities, including Charité Berlin in Germany, Monash University in Australia and Tel Aviv University in Israel, as well as Dartmouth, Duke, Harvard, UCLA and Yale. As the project leader, Maoz also focuses on his own research, which explores volition, decision-making and moral choice. With a combination of techniques such as intracranial recordings, behavioral studies and theoretical modeling, he develops a computational account of volition, examining the decision-making processes that lead to voluntary action.

His work has potential to affect legal decisions as well as the teaching and application of ethics. There are also economic and healthcare implications. “Studying this is important because it teaches us about processes in the brain and how things like volition come about,” Maoz said in an interview with Science magazine. “That has implications for the legal system, for example, which distinguishes between voluntary and involuntary actions. It may also have implications for motor disorders like Parkinson’s disease, where people have a hard time with self-initiated movements. If we understand more about how the brain produces self-initiated movements, we may be able to add another layer to the Parkinson’s

Uri Maoz, Ph.D.

research. I would say the more we understand about the brain, the better we can do in many areas.” At Chapman, the Brain Institute has a research presence at both the main campus in Orange and at the Rinker Health Science Campus in Irvine. Topics of inquiry range from psychopathology to self-regulation through biofeedback. One experiment – metacognition in deliberate and arbitrary choices – explores how the timing of people’s judgment about their actions and intentions changes across the types of decisions being made. This experiment builds on the groundbreaking work done by physiologist Benjamin Libet in the 1980s. Libet found that the brain signaled a physical action before participants reported that they had even decided to move. With such research as groundwork, Maoz and his colleagues seek to distinguish between conscious and unconscious decisions, between the planned and the arbitrary, the authentic and the contrived. Perhaps you are still curious how it will all unfold. You are not alone. Maoz admits that as a scientist, he doesn’t know what is required to say that we have free will. But he can consider whether humans meet the requirement. “Do humans possess that? This is an empirical question,” he says. “It may be that I don’t have the technology to measure it, but that is at least an empirical question I could get at.”

THE MYSTERIOUS CASE OF THE MISSING MANGROVES

Mixing artifi cial intelligence with old-fashioned ingenuity, Professor Hesham El-Askary and his team put a coastal forest back on the map.

BY BRITTANY HANSON

What do you do when an intricate ecosystem of trees and roots disappears? Th is was the mystery presented to researcher Hesham El-Askary, Ph.D., a professor in Chapman University’s Center of Excellence in Earth Systems Modeling & Observations.

He was alerted to the missing mangroves by NASA and U.S. Geological Survey joint program Landsat satellite images of the Arabian Gulf’s Jubail conservation area. Th ey showed startling discrepancies as to how much of the coastline was covered in native mangroves — trees that support diverse ecosystems and thrive in salty conditions. From 2000 to 2014, it looked like the entire forest had disappeared.

It turns out that while Landsat images make it easy to recognize variations in topography, they are far less eff ective at revealing diff erences in vegetation. As researchers studied bird’s-eye views of the mangrove distribution area, the submerged mangroves were being confused with salt marshes and macro algae. Th is is where the artifi cial intelligence comes in. El-Askary and his team used programs known as the Submerged Mangrove Recognition Index (SMRI), the Normalized Diff erence Vegetation Index (NDVI) and Classifi cation and Regression Trees (CART) to gain some clarity.

Th e programs allowed researchers to sort through the visual density in satellite images and determine which part of the Jubail coastline was mangroves and which part was marsh, El-Askary says. CART was 95% accurate in identifying mangroves, while the other programs achieved 90% accuracy. With this honor-rollworthy lineup of programs, El-Askary and his team were able to “fi nd” the forest through its trees. Th e team’s fi ndings directly support conservation eff orts by the Environmental Protection Department of Saudi Aramco, Saudi Arabia’s state oil company. Th e research will also be used by the Center for Environment and Water of King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals in Dhahran.

“Both are working closely with us on the preservation of these marine ecosystems,” says El-Askary. “Our mapping techniques will be key in establishing a better understanding of how they are aff ected.” Going forward, the Chapman team’s fi ndings are likely to be applied wherever Mangrove forests are studied – especially to validate USGS datasets, since that information is generally considered a baseline for mangrove mapping and monitoring.

Th e team’s approach of combining traditional AI algorithms with knowledge-based expertise may also be applied to solve satellitedata issues in other areas of research, such as analyzing crop growth, planning cities and monitoring traffi c patterns. And for the time being, mangrove forests of the world remain safely in sight.

Professor Hesham El-Askary and Ph.D. student Wenzhao Li use computer technology to "fi nd" mangrove forests that had been missing from satellite images.

Disappearing Trees

You can fi nd mangrove forests in 123 countries – most of them in tropical latitudes. Th e arid Middle East accounts for about 0.4% of global mangroves.

Th ese coastal trees and shrubs play an important part in regulating climate by sequestering atmospheric carbon. Th ey also help moderate extreme weather events such as cyclones and tsunamis.

About 90% of global mangroves are critically endangered. Th ey are nearing extinction in as many as 26 countries.