7 minute read

■ Cover Story

LOCAL FOCUS

Charleston inspires, cultivates local filmmaking

By Sydney Bollinger

The Lowcountry’s charm and beauty has been documented in films like The Notebook and Forrest Gump, but in recent years, production companies have chosen Charleston as the backdrop for new, high-profile TV and film projects.

Both Netflix’s Outer Banks and HBO’s The Righteous Gemstones have filmed in Charleston. Along with the success of Bravo’s Southern Charm and Halloween installments, the Charleston area has seen a recent uptick in interest from producers looking for picture-perfect backdrops and good quality of life.

As the local film industry grows, more filmmakers, crew members, and other creatives are moving to the area, interested in seeking new opportunities for film and production.

Many large productions that come to Charleston rely on local producers and filmmakers to navigate the city. H. Timothy Grady, owner of Ebb & Flow Pictures, often gets called in to help out-of-town filmmakers headed to the Holy City.

“My job is logistics and coordinating — making sure everybody’s on the same pa ge, and getting permits from the city, the towns and all the different municipalities,” Grady told the City Paper.

Charleston-based shows, including “reality” shows like Southern Charm and scripted comedies like Gemstones, showcase the city and help bring new productions to the area. Some filmmakers bring their own crews from L.A. or New York, but others, like The Righteous Gemstones, hire local crew and technicians, according to Grady.

Productions that focus on hiring Charleston professionals often provide a local avenue for aspiring filmmakers to get started, rather than moving to Atlanta or other Southeast film hubs.

“It’s a perfect place for beginning filmmakers … [It’s] a lot easier to get connections and really work through the ranks and be able to ask more questions and not just be another one of a million,” said Drew Glickman, a former Charlestonian who has worked on projects for National Geographic and Netflix’s Explained.

“The nice thing about the Charleston community is that there is so much up-andcoming industry that I was able to work my way up … As in: making a name for myself,” he said.

Student filmmakers also have many opportunities to get involved in the local industry. Both College of Charleston and Trident Technical College offer film-related programs.

CofC’s film studies students and Film Club members host the annual Student Film Festival every spring. Having begun in 2006, it is one of the longest-running film festivals in Charleston.

Trident’s film production program assists students with getting positions on productions and making connections with industry professionals to further their careers as film technicians and producers.

Rebecca Pryce, film department coordinator at Trident Tech, said just looking around a local set is a testament to the strength of the school's program.

Trident alumni have gone on to produce for major clients, including Zappos and CNN, she said. Some students choose to work on major productions while also furthering their own independent projects.

Charleston may not be a traditional film hub, but Pryce said there is “tremendous upside to a smaller market.”

“From my perspective, there is a strong community here that looks after their own,” she said.

The local filmmaking community and Charleston’s history also fosters storytelling based on the city’s history.

Travis Pearson, whose 2015 film, America Street, screened at a satellite event for 2021’s Sundance Film Festival, gains much of his inspiration from the Charleston area, its history and his own background.

Pearson’s focus on telling local stories through film has its roots in history.

Pearson is currently working on his second feature-length film, The Rose Boys, a coming-of-age story about two boys who sell palmetto roses downtown. The project will move to production in 2022.

Pearson admits that Charleston wasn’t always a good place to start as a filmmaker. “You had to go where the money was,” he said. “But that’s slowly but surely changing, because the equipment is becoming more accessible.”

The Lowcountry is home to several independent filmmakers who rely on affordable equipment and software and release their projects online through Vimeo, YouTube or streaming services, such as Tubi, which is owned by Fox.

Felicia Rivers, founder of Geechee One Productions, shoots many of her films locally using local actors to “showcase the city and the world we live in.”

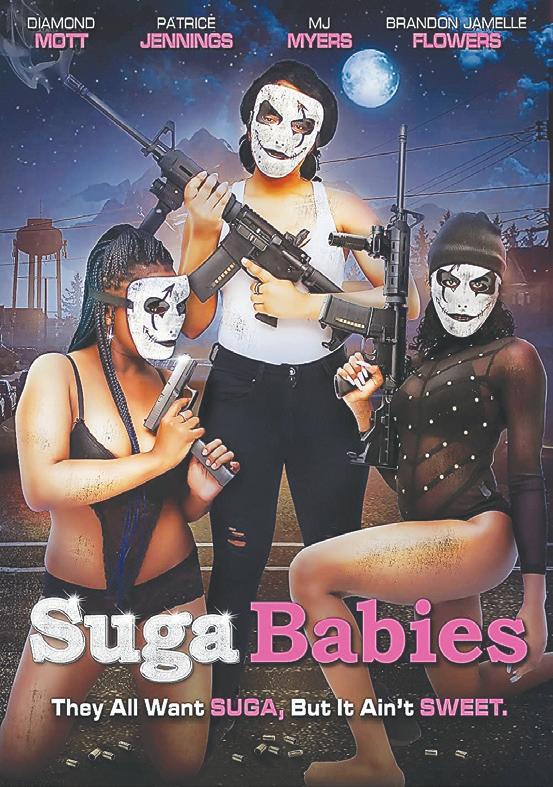

Her first full-length film, Suga Babies, had its Tubi debut on Nov. 1. She also has upcoming projects, including a drama, which will address police brutality toward the Black community.

Rivers said she expects the industry to grow even more in the next decade.

According to Grady, local governments could make the permitting process easier for filmmakers looking to use local venues and locations, which would promote even more growth to the industry.

He also hopes to improve relations between Charlestonians and film producers.

“People that are from South Carolina are the nicest people you’ll ever meet, but they’ve also been taken advantage of,” said Grady. So remember, he said, when

Pryce

Images provided

Travis Pearson’s 2015 film, America Street (above), recently screened at a satellite event for the 2021 Sundance Film Festival. Pearson (right) says he’s currently working on new a production, The Rose Boys.

Rūta Smith

crews show up, the good ones will check all the boxes.

Relationships between South Carolinians and film producers may continue to grow, especially as Carolina Film Alliance (CFA) looks to expand the state's film industry.

The group is gearing up for the next state legislative session, which begins in January. The session comes just as the S.C. Film Commission announced the departure of state Film Commissioner Tom Clark, who will be succeeded by Matt Storm, who has worked with the S.C. Film Commission since 2019.

In the next year, CFA hopes to develop the S.C. film production workforce with funding from the Department of Employment and Workforce (DEW), according to a November legislative update. The group also plans to continue advocating for wage and supplier rebate funds.

South Carolina currently offers $16 million in film incentives per year, while North Carolina offers $31 million and Georgia has an uncapped tax incentive. In September, the S.C. Film Commission was offered an additional $15 million to bring new productions to the state.

In addition to the Film Alliance offering some assistance for productions, Indie Grants also awards up to $35,000 for short films produced by South Carolina filmmakers.

Those incentives help companies that come to S.C. and hire Trident students to work on crews, help get filmmakers opportunities with major film festivals and expand the experience of the local film industry.

There’s always hope for more in the future, but for now, Grady says, “The good thing is the film business is alive and well.”