The Charleston School of Law is proud to celebrate the opening of the International African American Museum in the Lowcountry.

Our faculty, students, alumni, and staff at Charleston Law are committed to fostering diversity through our teaching and learning, community service, and dedication to our clients and the legal profession. We hope you will join us in welcoming the IAAM to Charleston. charlestonlaw.edu/diversity

Debra Gammons Distinguished Visiting Professor

Sherman Brown 3L student

Alexandria Jones Class of '23

Melanie Regis Assistant Professor of Law

Debra Gammons Distinguished Visiting Professor

Sherman Brown 3L student

Alexandria Jones Class of '23

Melanie Regis Assistant Professor of Law

EDITOR and PUBLISHER

Andy Brack

ASSISTANT PUBLISHER

Cris Temples

MANAGING EDITOR

Samantha Connors

NEWS

Staff: Skyler Baldwin, Herb Frazier, Chelsea Grinstead, Chloe Hogan, Hillary Reaves

Interns: Owen Kowalewski, Alex Nettles

Contributor: Damon Fordham

SALES

Advertising Director: Cris Temples

Account team: Kristin Byars, Ashley Frantz, Crystal Joyner, Mariana Robbins, Gregg Van Leuven

National ad sales: VMG Advertising

More info: charlestoncitypaper.com

DESIGN

Art Director: Scott Suchy

Art team: Déla O’Callaghan, Christina Bailey

DISTRIBUTION

Circulation team: Chris Glenn, Robert Hogg, Stephen Jenkins, David Lampley, Spencer Martin, John Melnick, Tashana Remsburg

By Andy Brack

By Andy Brack

But finally — after generations of whippings, violence and lynchings as well as a civil war that ripped apart the nation — we are at a historical tipping point. With the nation’s 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence approaching in just three years, now is the time we in Charleston must try to better appreciate and honor the toil of enslaved Africans and their descendents who built great wealth in a country that claimed to offer freedom for all, but did not.

Journeys is our special commemorative magazine that welcomes the International African American Museum (IAAM) to Charleston and the world. We encourage you to read the stories in the pages ahead that profile the people who shaped America’s food, music, arts and politics.

Now is the perfect time for a museum dedicated to telling generations of stories stemming from the lives of enslaved Africans brutally brought to what became the United States. And now is the perfect time for Charleston, where two of every five of the enslaved disembarked from cruel slaving ships that fueled chattel slavery, to embrace this museum built on a wharf where importation of people ended in 1808.

“This museum is needed now more than ever,” Charleston Mayor John Tecklenburg said May 10 during a panel discussion in which the museum was honored by the Riley Institute at Furman University. In passionate remarks, he said the IAAM would fill in the gaps of history here and around the world with fuller stories to help explain ongoing disparities in American society often experiencing denial, conflict and rancor.

The museum will pull together White, tan, brown, Black and other Americans to give richer looks at the history and culture that shaped our country. Even more exciting is the new IAAM Center for Family History which will serve as a genealogical hub to connect descendants of enslaved Africans to their lost family pasts. The museum will help to fill voids ignored by history books and allow many Americans to reclaim their family stories and heritage.

Dr. Tonya Matthews, president and CEO of the IAAM, said the museum will be a site of pilgrimage that will become transformative.

“We’re providing the means for folks to unearth their own stories,” she said recently, adding, “We bring people here to learn. We are a site of journey and an end point for so many folks.”

And for Charleston and the South, which for generations has mostly avoided deep discussions about the scar of racism and a past that profited from slavery, the IAAM will have a broader role to spark new discussions and better understanding of the past and present.

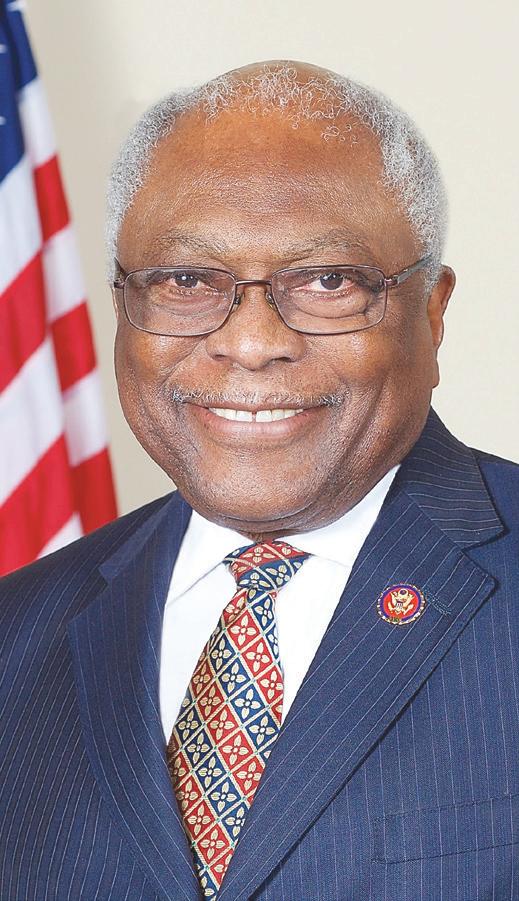

“This museum brings with it value,” U.S. Rep. Jim Clyburn, D-S.C., said in a recent short film. “It means that South Carolina is paying homage to the diversity of its citizens and that South Carolina is not running away from its history — that South Carolina is being true in our pursuit for a more perfect union.”

When the museum opens June 27, we encourage you to visit often to get a better sense of the whole story of historic Charleston. Give thanks to visionaries like former Mayor Joseph P. Riley Jr. who pushed to build the museum. Quench your curiosity about what really happened in the past, not just moonlight and magnolias mythmaking.

Now is the time to welcome this transformative museum and use it to heal wounds that still blister the present.

The museum will be open 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesdays through Sundays starting June 27.

The museum will help to fill voids ignored by history books and allow many Americans to reclaim their family stories and heritage.

The enslaved Africans brought here on dirty cramped ships centuries before anyone alive today was born would never have imagined a museum built to explain their journey and impact.Ellis Creek Photography Andy Brack is editor and publisher of Charleston City Paper

Dominion Energy is humbled and honored to bring The International African American Museum (IAAM) to light in Charleston, South Carolina.

The vision of the museum is to illuminate the influential histories of Africans that entered America through Charleston and celebrate some of the country’s leading thinkers, businesspeople, artists, musicians and heroes.

At Dominion Energy, we believe in understanding our history and where we have been so we can all come together, move forward and work to make our homes, lives and communities better.

Nine core galleries, a special exhibit space and a genealogy center in the new International African American Museum (IAAM) present a sweeping story of the forced migration of Africans to America.

It’s a museum like no other — and lives up to its name as being international.

The IAAM’s galleries reveal the realities of the slave trade and plantation life while presenting the skills and culture of people of African descent and their contributions to this country.

The museum, built on the site of a 19th century slavetrading port on the Cooper River, faced several delays, but opens June 27 to the public. Delays and changes have increased the museum’s cost from $75 million to nearly $100 million, said city of Charleston spokesman Jack O’Toole. The city owns the building, and leases it annually to the IAAM for $1. The museum’s construction and completion was fueled by more than $150 million from state and local governments, companies, nonprofits and individuals.

In a 2000 state-of-the-city address, then-Mayor Joseph P. Riley Jr. announced his desire to build the museum. The following year, a site across from the South Carolina Aquarium was selected. But three years later, plans changed, and the city paid $3.5 million for the current site, known as Gadsden’s Wharf.

continued on page 10

When the IAAM opens, its story starts outside at two yet-to-be-finished black granite walls memorializing the more than 700 Africans who froze to death in 1806 at the wharf. The memorial walls fit within the concrete outline on the ground of the storage house where the enslaved people perished during an unexpected freeze. To represent them, a series of human figures appear as if they are emerging from the ground. The black polished walls bear a quote from the late Maya Angelou: “And still I rise.”

In fact, the long, narrow museum, supported 13 feet off the ground by 18 cylindrical pillars, appears to rise from the ground where the enslaved died. IAAM President and CEO Tonya Matthews said understanding why the building was raised blunts earlier criticism that the museum on paper is not visually striking.

“The design of this building is what gave rise to the African Ancestors Memorial Garden that sits under it,” she said in 2022 when she gave the City Paper an exclusive tour of the museum. Art installations in the garden, she explained, cover ground which essentially has become the museum’s first floor, a design she inherited when she was selected in March 2021 to lead the museum.

Placing the museum at the former slave port, Matthews said, illustrates “the greatest gifts African Americans have to give — our ability to simultaneously hold the sensation of trauma and joy.”

continued on page 12

Under the museum, a wide staircase ascends into the center of the building’s skylight atrium and a glass front entrance. The stairs provide seating in a shaded amphitheater-like setting for community events with a cool breeze from the river. At the building’s east end, overlooking the Cooper River, large exhibits in galleries are arranged by geography and culture. At the west end with a view of the Concord Street soccer field, galleries are arranged chronologically.

In addition to the memorial wall, another solemn presentation is at the building’s harborside in two small flanking mini galleries in the larger Atlantic Worlds Gallery.

On the black walls of the Port of Departure mini gallery are the names and ages of scores of young Africans, including Houa, 7, Lome, 14, and Halem, 22. They were among the captives who were freed after illegal slave ships were intercepted in the early to mid-1800s after many countries, including Britain and the United States, outlawed the transAtlantic slave trade. The names, ages and other details of the Africans became part of legal records that were later used to develop a slave trade database.

In the opposing Port of Arrival mini gallery, black walls are covered with the Americanized names of captives, such as Solomon, Venus and Poor Man.

“These names are a bit easier to come by from slave and plantation records,” Matthews said. “These are the simplest galleries, but the ones that say the most.”

Three of the nine galleries tell the stories of rice, culture and religion. Slavery is told through rice in the Carolina Gold Gallery. The Carolina Connections gallery displays scenes of modern South Carolina and other African American sites across the state. The Gullah Geechee Gallery holds a replica of a praise house with the sounds of a worship service recorded at Johns Island’s Moving Star Hall Praise House on River Road. At the museum’s west end, the staff in the Center for Family History will help visitors trace their genealogy. The staff will also direct visitors to DNA testing so they can use science to find their African roots.

During the tour with the City Paper, Matthews acknowledged the IAAM’s story about slavery will not be widely popular.

“Museums are places where you are allowed to show up and admit you don’t know something,” she said. “When you are at a museum, you are learning. An environment like this is really helpful for conversations like that.”

The idea of a Black history museum swirled in former Charleston Mayor Joseph P. Riley Jr.’s mind more than 20 years ago as he read the story of a wealthy plantation family who enslaved nearly 4,000 Africans in Berkeley County.

For two centuries, the Africans cultivated rice on 25 farms and plantations owned by the Ball family along the upper end of the Cooper River. It’s estimated that 100,000 descendants of those “Ball slaves” are scattered across the United States, including a family in North Charleston.

This shocking revelation gleaned from the Ball family plantation records and ancestral lore jumped from the pages as Riley

Congratulations on this remarkable achievement honoring African American heritage and contributions.

We were honored to be able to support this effort, and we applaud the other sponsors, founders and all involved in making this visionary project a reality.

Reality from page 14

read Edward Ball’s award-winning 1998 book, Slaves in the Family.

Ball’s account of his family’s role in plantation slavery “showed me the horror of the brutal ship crossing and the unspeakably harsh life that the survivors would face,” Riley told the Charleston City Paper. “It lit a fire in my mind. The book was so powerful that I decided we needed to build a museum to tell that story.”

In January 2000 at the start of Riley’s seventh term in office, he pledged that his long-term vision for the city would include a museum focused on African American history. A year after Riley pledged support for a museum, Virginia Gov. Douglas Wilder announced plans for a national slavery museum in Fredericksburg. It was never built. Two decades later on June 27, however, in Charleston, an eager public will finally see the inside of the International African American Museum (IAAM) built along the Cooper River, 30 miles downstream from the Ball family rice fields.

In an email, Ball wrote: “I remember when Mayor Riley called me into his office in 1998 after he had read my book and asked, ‘Do you think there could be a museum that tells the story of slavery in the lowcountry?’ I said, ‘Yes, but you’ll face a wall of white opposition.’ Twentyfive years later, vindication. It moves me that Mayor Riley says I’m the author of this museum,” said Ball, who now lives in New Haven, and is working on a book about the domestic slave trade. “To write a book is one thing and to put a monument on the ground is another. Mayor Riley has put this stone on the ground.”

When the IAAM announced on Feb. 28 on its Facebook page that a twice-delayed opening date was finally set for June, people reacted. Keisha Hunter of Los Angeles wrote: “Fantastic update! Very excited about returning to South Carolina to witness this history!” Kayci Griffin of Hanahan responded with: “This is the news I’ve been waiting to see! Looking forward to taking my homeschooled children. I intend on using IAAM as an integral part of their education.”

They will be among the thousands of people who are expected to pour into the Port City this summer to enter the museum that sits on the former site of Gadsden’s Wharf, once a slave trading

site where hundreds of Africans perished in the winter of 1807 while waiting for the auction block.

Riley described the museum as a splendid reflection of his vision “to honor the untold stories of the African American journey at one of our country’s most sacred sites. It stands as a testament to what can be accomplished when an initiative seeks and demands excellence in every aspect of its development. Our commitment to excellence never relented over the 23 years from idea to opening.”

But during that time the city could not shake the obvious contradiction of the location for the $120 million museum. A museum that honors African American history and the horrors of Gadsden Wharf is adjacent to an open field that was once a predominantly Black neighborhood now erased due to gentrification. Riley said he was never concerned the choice of the museum's location would be criticized because of its

proximity to the former Ansonborough Homes at the east end of Calhoun Street.

“Gadsden’s Wharf is sacred ground,” the former mayor said. “The history of that land is so important to the stories the museum will tell.” The housing project was in a very low-lying area and experienced significant flooding in September 1989 during Hurricane Hugo.

Construction of the nearby South Carolina Aquarium revealed underground sludge from a coal gasification plant. As a result, it was necessary to relocate scores of Ansonborough residents, demolish the projects, treat the soil and cap the site, Riley said.

“This afforded a great opportunity to relocate [Ansonborough] residents to scattered site public housing throughout

“Gadsden’s Wharf is sacred ground. The history of that land is so important to the stories the museum will tell.”

Former CharlestonMayor Joseph

P. Riley Jr.

The International African American Museum tells powerful stories and lessons about enslaved Africans forced to come to Charleston, their lives here, and the significant impact they had — and their descendants continue to have — on today’s culture, commerce and communities.

Santee Cooper proudly powers people’s homes and businesses across South Carolina. The IAAM powers hearts and minds.

santeecooper.com

the city and on Johns Island,” Riley said. “Scattered site public housing is something I championed as mayor. I was determined to build beautiful new public housing on vacant lots throughout the city instead of monolithic housing ‘projects.’” The decision to remove the housing project because of the pollution, however, has not prevented new upscale development on the fringe of the former Ansonborough Homes site.

To shepherd the museum idea, Riley asked his friend U.S. Rep. James E. Clyburn, D-S.C., to lead a steering committee made up of local people to begin the process of planning for the museum. Clyburn, a Sumter native and a former history teacher at Charles A. Brown High School on the east side of the city, had seen how development has changed the predominantly Black community and Gullah Geechee communities along coastal South Carolina.

Clyburn said his approach to mitigating the effects of development on African American history and culture went into his efforts to win congressional approval in 2006 for the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor. The gradual disappearance of sweetgrass, used to make African-inspired coiled sweetgrass baskets, is one of the downsides to coastal development, he said.

“We can say that [development] is happening, and I hate that it is happening or get involved in it to see what you can do to … make the best out of this,” he said.

The IAAM is a lasting memorial for the people who lived and died on the east side of Charleston and for the Africans who arrived in Charleston through Gadsden’s Wharf, he said. The wharf’s location is the best site for the museum than a tract of city-owned land closer to the South Carolina Aquarium, he said.

To tell Charleston’s link with West Africa’s Rice Coast museum, planners had hoped to secure a special artifact to illustrate the heart-pounding moments during the transition from freedom to slavery.

Captured Africans bound for slavery in America took their last steps on African soil along a jetty at Bunce Island near Freetown, Sierra Leone. They walked the stone jetty before they were ferried on smaller boats to ocean-going vessels. IAAM planners hoped to obtain a Bunce Island jetty stone for a museum display.

“We continue to pursue this most worthy idea, but the stone memorial will not be in place for the opening,” Riley lamented.

It is possible that in 1756 a 10-year-old Susu girl from Sierra Leone may have walked the Bunce Island jetty before she was brought to Charleston and later purchased by Elisa Ball, who took her to one of his plantations in Berkeley County. Ball named the girl Priscilla. Edward Ball tells the story of Priscilla’s Charleston descendants in Slaves in the Family

In 2005, Sierra Leoneans embraced Priscilla’s eight-generation great-granddaughter Thomalind Martin Polite, a North Charleston school teacher, who was invited to Sierra Leone for an event dubbed “Priscilla’s Homecoming.”

Polite is linked to Priscilla through the Ball plantation records and the Hare, a New England-based slave ship

Thomalind Martin Polite traced her ancestry back to a 10-year-old enslaved girl brought to Charleston in the 18th century. At right, Polite is among those who traveled to West Africa for a homecoming.

that brought Priscilla to the Carolina Colony. Finding both ship and plantation records to document the journey of a captured West African to America

is rare in genealogical and historical research, scholars said.

As Polite toured the Freetown area, Sierra Leoneans embraced her, believing she had returned her ancestors spirit to her homeland. Polite’s story is featured in the IAAM’s Center for Family History. Its staff will help visitors trace their genealogy. They will also direct visitors to DNA testing so they can use science to find their African roots.

Although Polite has not yet seen the center’s exhibit that features her picture, she said, “It is an honor to be prominently presented in a historical fashion, but it is not about me. It is about my ancestors. I think the focus should be on their journey and their lives.”

1526

Africans are thought to have first arrived in South Carolina as part of a Spanish expedition from the Caribbean.

1822

A freedman of African descent, Denmark Vesey, was accused of leading a widespread and wellplanned rebellion that was foiled by the White elite. Vesey and 34 others were hanged. The Citadel later was built as a reaction and to increase military control over the Black majority.

The African presence in South Carolina is closely linked to trans-Atlantic crossings made by early European explorers and later captured West Africans. From the earliest of times, enslaved Africans had a major impact on the lives of newcomers to the Americas through the backbreaking work to build a lucrative ricebased economy to their major influences on foodways, art, music and culture. Here’s a brief history of African Americans in South Carolina.

According to the International African American Museum, more than 12.5 million African captives were forced into the transAtlantic slave trade, most from West and West Central Africa. An estimated 1.8 million died in the two-month, cramped, inhumane crossing, often called the “Middle Passage.”

1670

England’s eight Lords Proprietors settled Charleston as a business venture, soon discovering rice to be a crop that would provide economic stability for the new Carolina colony. They used the free labor of enslaved people from West Africa’s traditional rice-growing region to build the colony.

1708

The number of enslaved Africans and their Gullah Geechee descendants in South Carolina were the majority of the colony’s population, which was about 8,000 people.

1739

About 100 Black insurrectionists seized firearms and tried to fight their way to St. Augustine, Florida, where the Spanish promised them freedom. This was the “Stono Rebellion,” a revolt that was put down with at least 60 executions. The following year, the state legislature passed oppressive “slave codes’’ to curb travel, growing food, possession of money and drum-playing.

1829

The Rev. Daniel Payne, a free Black man, opens a school for free Blacks, but the legislature three years later forced it to close. Payne later became a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

1850

The number of enslaved Africans and their descendents in South Carolina is 57.6% of the state’s population.

1808

A congressional ban on slave imports took effect Jan. 1, 1808, including at Gadsden’s Wharf, which was one of the landing locations for enslaved people arriving in Charleston. The site is where the International African American Museum is now located.

1860

South Carolina secedes from the Union. The following year, the Civil War started with shells fired at Fort Sumter in the Charleston Harbor.

continued on page 22

The South Carolina Aquarium is honored to welcome the International African American Museum to the Charleston waterfront.

Our home on the Charleston Harbor is a reminder of our inextricable link to the ocean, and to our complex human history. Together, we will learn about the past, educate in the present and inspire a future of empathy and action.

1862

Robert Smalls, a Charleston harbor pilot, took control of a Confederate steamer, the Planter, and presented it to the United States Navy. It was converted into a Union ship used throughout the war. Smalls later became a state legislator and congressman.

1868

After U.S. troops registered Black voters in 1867, a new majority-Black General Assembly takes control and adopts a new constitution, which required a system of free public schools.

1869

The Charleston branch of the Freedman’s Bank for freed slaves was established. Four years later, it has 5,500 depositors and assets of almost $350,000.

1876

Civil disturbances by racist forces throughout the state, but particularly in Black majority areas, threatened leadership of Republican Black elected officials and sought to repress the Black vote. Reconstruction spiraled out of control. Fear and intimidation returned to Black communities as violence escalated.

1877

With the federal Compromise of 1877 came the end of the Reconstruction era and return of the White elite to power. In the next few years came a return to repressive poll taxes and literacy tests and intimidation. New Jim Crow laws took away freedoms, keeping African Americans in positions of inferiority.

1879

More than 200 Black emigrants leave Charleston for Liberia, illustrating the desire by many that the U.S. could never be a free homeland for people of African descent. The Rev. Richard Cain, a national AME leader, who served in Congress, sponsored a bill to pay passage.

1895

The S.C. Constitution of 1895, which is still in effect today, was passed by White elites to institutionalize segregation and harsh Jim Crow laws to limit freedoms for South Carolina’s Black citizens.

1917

Marked the founding of the Charleston chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

The Charleston Race Riots occurred when a group of White sailors stormed King Street looking for a Black man who allegedly didn’t buy them the liquor they wanted. The sailors attacked Black Charlestonians, three of whom were murdered. The killers were arrested, and a biracial committee was established to prevent future violence.

1945

Nearly 1,000 workers, most of whom were Black women, at the Charleston Cigar Factory had a work strike to demand higher wages and better working conditions. Striking workers sang “We Will Overcome.” The song was later changed to become the anthem for the modern-day civil rights movement.

1952

U.S. District Judge Waties Waring of Charleston wrote an important dissent in the Briggs v. Elliott school desegregation case that said “segregation is per se inequality.” The decision formed a key argument in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision by the U.S. Supreme Court two years later.

1957

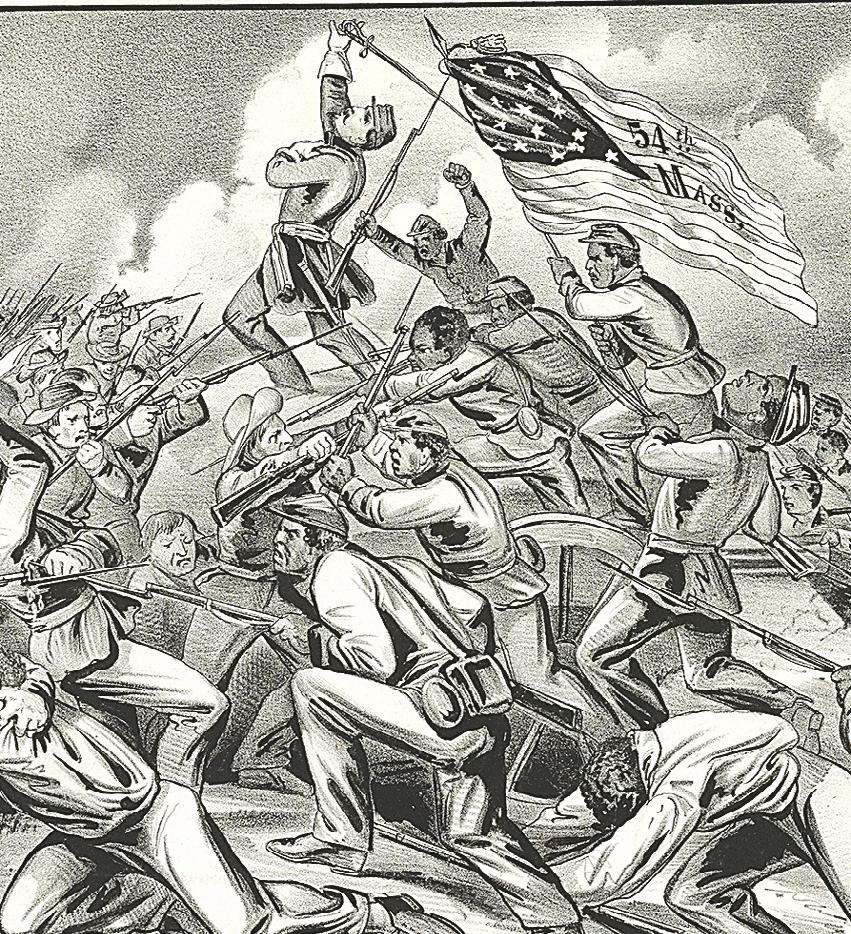

1863

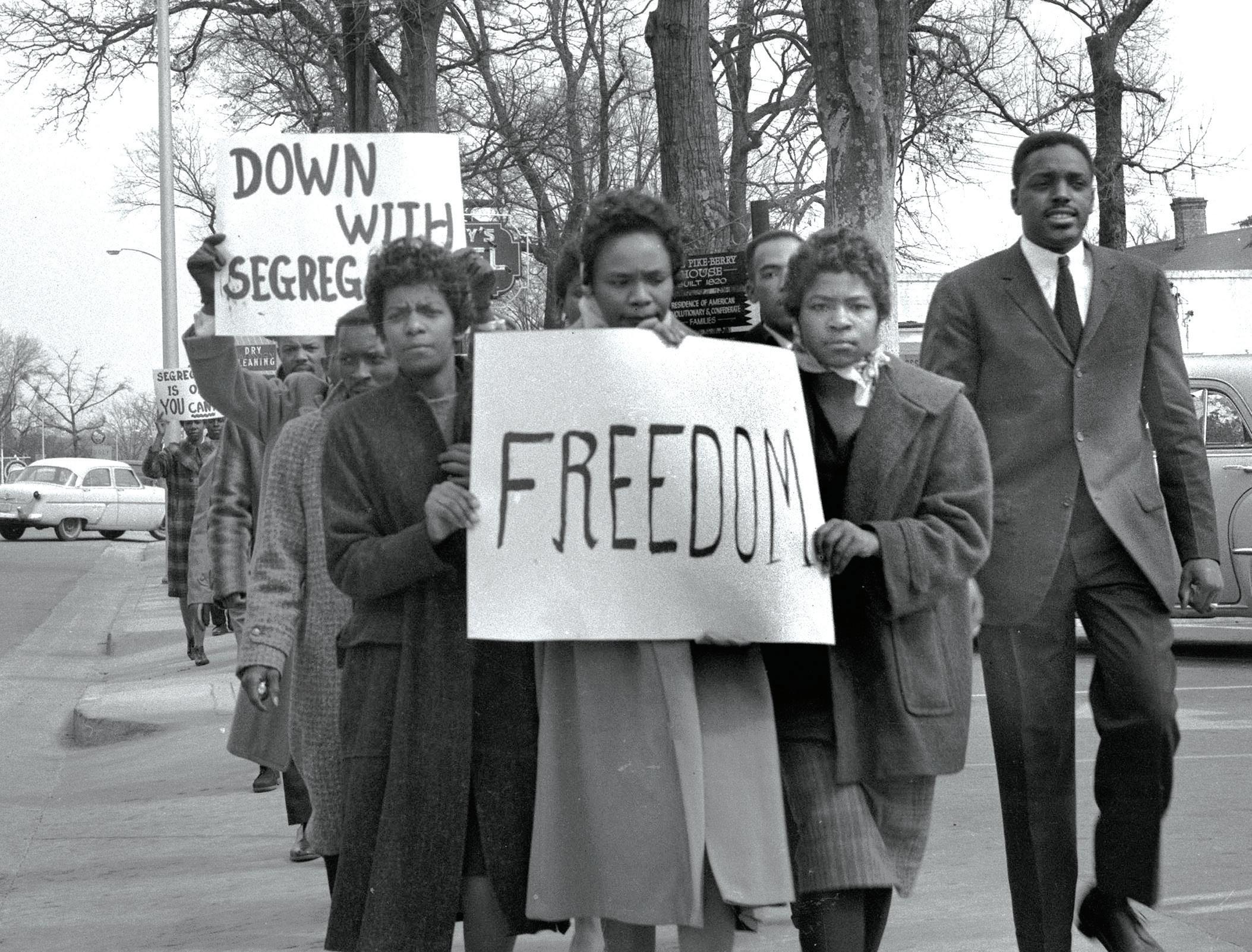

More than 1,500 free Black Union troops died, were wounded or were captured in the Second Battle of Fort Wagner, which is depicted in the movie Glory While a defeat for the Union, it spurred more free Black troops to sign up for service and gave the Union Army a numeric advantage.

1865

The nation’s first Memorial Day reportedly was held in Charleston on May 1 at Hampton Park when 10,000 people gathered to honor 257 Union dead.

1891

The Rev. Daniel Jenkins established an orphanage in Charleston that became a key international influencer of jazz music and toured the nation and world in the years to come.

A “citizenship school” opened on Johns Island by activists Esau Jenkins, Septima P. Clark and Bernice Robinson to train Black adults how to register for vote and fill out other forms. Clark later was called “mother of the movement” by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. for schools across the Deep South. In 1975, Clark was the first Black woman to be elected to the Charleston school board.

1962

King spoke at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston in support of local voter registration and civil rights efforts.

Charleston schools are the first in the state to be forced to comply with the 1954 Brown v. Board desegregation decision. That year, a federal judge in South Carolina cleared the way for 11 Black students to attend and desegregate Rivers High School in Charleston and other schools in the city.

1969

After 12 Black workers were fired from the Medical College Hospital in Charleston, a two-month strike occurred that led to interruption of commerce and marches, one of which had 10,000 protesters. A settlement eventually occurred leading to better pay and working conditions and the creation of the state’s Human Affairs Commission.

The city of Charleston appointed Reuben Greenberg, an African American, to be its police chief.

Following a mandated congressional redistricting, Sumter native Jim Clyburn became the first Black congressman elected in the state since 1893. He represents a district that stretches from Columbia to Charleston to the Pee Dee.

A 6-foot historical marker is placed on Sullivan’s Island near Fort Moultrie to honor enslaved Africans who died on the way to America or arrived in bondage in Charleston Harbor.

Charleston Mayor Joseph P. Riley Jr. publicly proposed that the city tell its full history through a museum that shines a light on long-ignored stories of African American experiences. This was the first step in what became the International African American Museum (IAAM).

2005 Clyburn becomes the inaugural board chair of the IAAM.

2014

The city of Charleston acquires Gadsden’s Wharf, a 2.3-acre waterfront lot on the Cooper River, to be the IAAM’s home. The same year, the museum’s design team is finalized.

The IAAM’s building design receives final approval from the city of Charleston.

Charleston City Council passes a resolution apologizing for the city’s role in slavery and the slave trade.

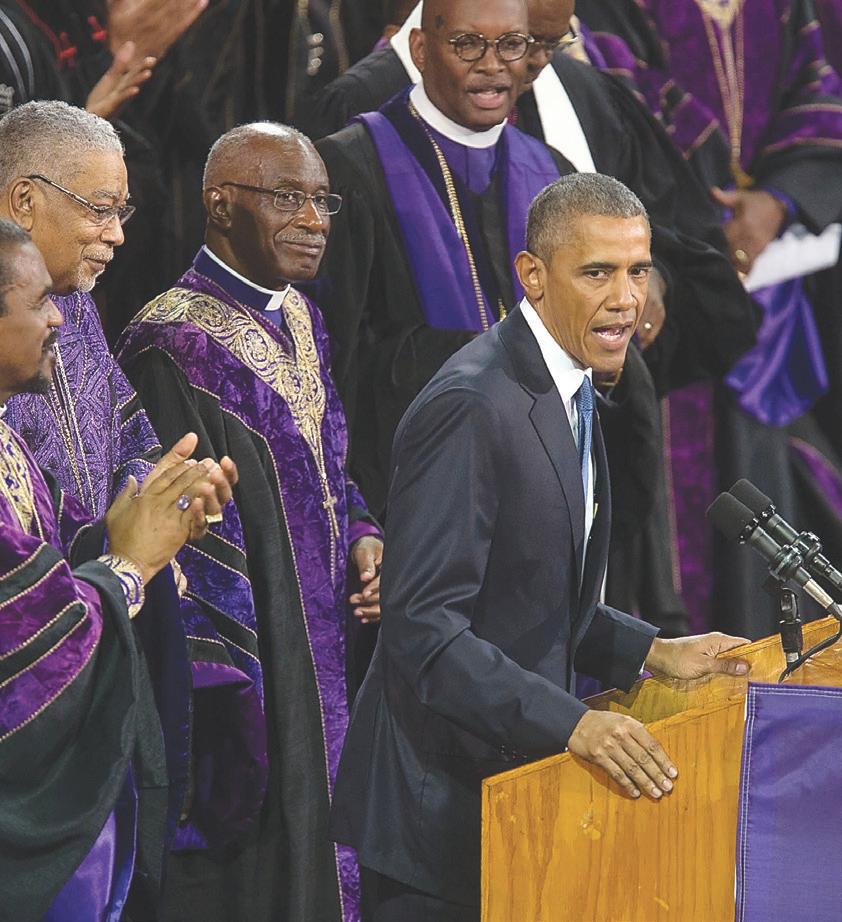

Nine worshippers are murdered at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston by a racist White gunman. The shootings haunted and galvanized the nation, giving impetus to the need for the International African American Museum. President Barack Obama gave a eulogy for one of the victims, the Rev. Clementa Pinckney, the church’s pastor and a state senator. During the eulogy, Obama led the mourners in singing “Amazing Grace.”

2020

Public support grew for the removal of a statue of former Vice President John C. Calhoun, a state’s rights supporter before the Civil War, from Marion Square. It was removed and put into storage.

2023

The IAAM opens in Charleston after raising about $120 million from government, corporate and private sources.

Sources include AfricanAmericanCharleston.com, the Lowcountry Digital History Initiative, Charleston County Public Library and International African American Museum.

Photos courtesy IAAM; Brenda J. Peart; Library of Congress; Brownie Harris, City of Charleston; Walter Albertin; Lawrence Jackson; Avery Research Center; Rūta Smith

It took two generations and the racial awakening of the civil rights movement for Porgy and Bess to come back home to where it all started.

The wildly successful international opera opened on Broadway in 1935 to world acclaim, but it wasn’t until 1970 that Porgy and Bess was first performed in Charleston.

And it wasn’t until an updated production in 2016 during Spoleto Festival USA that Charleston saw the opera again, rekindling the power of the work here and abroad, leading to important conversations about Porgy and Bess and its complicated relationship with its home turf. Porgy’s overdue homecoming is a story about how institutional racism has for too long deprived Charlestonians of this pivotal work in American cultural history.

The opera was adapted by George and Ira Gershwin from Dorothy and DuBose Heyward’s play Porgy, itself an adaptation of Charlestonian DuBose Heyward’s 1925 novel of the same name.

The work has become a lightning rod for controversy; it has to reckon with being an account of Black life as written by non-Black people in a time of Southern segregation.

“It was a healing process for Charleston, to finally see Porgy and Bess here.”

Charleston native, historian and archivist, Harlan GreenePhotos by Charles McKenzie Annette McKenzie Anderson portrayed Bess, along with Kent Byas as Crown, in Charleston’s 1970 production of Porgy and Bess Reuben Wright as Porgy during a dress rehearsal

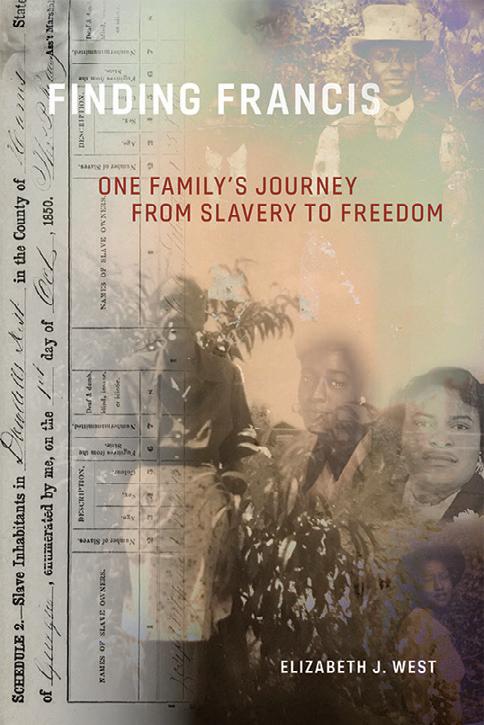

—AVAILABLE JANUARY 2024— 6 x 9, 304 pages, 27 b&w illus. Hardcover, $27.99

—AVAILABLE JANUARY 2024— 6 x 9, 240 pages, 79 b&w illus.

—AVAILABLE NOVEMBER 2023— 8.5 x 11, 224 pages, 40 b&w and 50 color illus.

—AVAILABLE OCTOBER 2023— 6 x 9, 176 pages, 8 b&w illus.

Porgy and Bess is based on a fictionalized 1920s Charleston. Porgy, a disabled Black street beggar, was based on the real life Charlestonian named Samuel Smalls. The opera deals with his attempts to rescue his love, Bess, from the clutches of Crown, her violent and possessive lover, and Sportin’ Life, her drug dealer.

Many Charlestonians are familiar with the world-renowned work, or at least its most popular George Gershwin aria, “Summertime,” now a much-recorded jazz standard.

The opera opens with a character named Clara, singing a lullaby to her child: “Summertime, and the livin’ is easy…”

The work is centered on the povertystricken residents struggling to survive in the tenement called “Catfish Row,” based on the real Charleston tenement nicknamed “Cabbage Row” at 89-91 Church Street. Then, like now, the hot Charleston summertime is not easy livin’, especially for these characters.

“Summertime” is a song about tension. The story of Porgy and Bess’s complicated relationship with Charleston is too.

Porgy and Bess premiered on Broadway in 1935 and was shown all over the world before Charleston finally put on a production at the Gaillard Center, (then called the Charleston Municipal Auditorium) in 1970, with a local cast.

“It was a healing process for Charleston, to finally see Porgy and Bess here,” said Charleston native, historian and archivist, Harlan Greene, the author of Porgy & Bess: A Charleston Story

Greene explained that there had been multiple attempts in Charleston to show first the play Porgy, and later the opera, which were thwarted due to the issue of integrating audiences. According to Greene, screenings of the 1959 motion picture adaptation of the opera starring Sidney Poitier and Dorothy Dandridge were banned in South Carolina.

1969 was an especially tense year in Charleston, and in South Carolina as a whole: It was the year of the hospital workers’ strike and sanitation workers’ strike. Upstate, in Darlington County in early 1970 was the Lamar bus riots.

60 minutes, The Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker and more press were in Charleston to cover the protests, but also ended up covering the 1970 Porgy and Bess production, according to Lauren Waring Douglas, a director, producer and Charleston native who’s creating a documentary on the 1970 production, called When Porgy Came Home.

I“The cast received Broadway-caliber reviews, and they were nationally accredited with a moment of racial healing,” Douglas said. “I sat there and I was floored, because I thought, wait a second, I remember sitting on some of these peoples’ knees as a child. And if I didn’t know about this, then I know that greater Charleston didn’t know as much as they should about it.”

“I thought to myself, how much more empowered would I be — or anybody born after 1970 — how much more empowered would we be if we knew there was a time when our community came together before in the face of tension and tragedy?

“So, I started making phone calls and reintroducing myself to people I had known my whole life,” Douglas said.

Douglas originally began the project with a goal to make a short film about the legendary visual artist Jonathan Green’s involvement with the second-ever Charleston production of Porgy and Bess, in 2016 for Spoleto Festival USA.

Douglas said Green told her his motivation in working on the production’s sets and costuming was to honor, and in some ways, correct, the opera’s representation of Gullah-Geechee culture.

“Jonathan told me he would do it because, one, we are going to honor

our architecture; we are going to honor Phillip Simmons and his ironwork. And two, we are going to honor the wardrobe. In past productions, people were dressed in slavery scraps. Jonathan Green was the one who was like, hold on, we were the seamstresses. We would make these ball gowns, and we wouldn’t save some fabric for ourselves? And he was right,” Douglas said.

“We have really unique architecture, really unique food, and Porgy and Bess reminds us of that fact,” said Douglas. “We have a really unique culture which inspired great work.”

Inspired by the Spoleto production and especially Green’s involvement with it, Douglas began researching to make a film. She started out by reading the 1925 novel Porgy, which made her actually consider dropping the project. She’d recently wrapped up work on the PBS special, America After Charleston, which explored race relations in the aftermath of the June 2015 shooting at Mother Emanuel AME Church.

Douglas said she decided that the PBS project had been “depressing enough,” and that she thought she ought to “preserve her sanity by not touching Porgy and Bess, which deals with such heavy topics as medical experimentation on Black bodies, domestic abuse, drug problems, prostitu-

Douglas has since interviewed countless cast members from the 1970 production, who tell her that the artistic success of the production was due to their real lived experiences with the subject matter.

“They tell me, Lauren, we know the part, we lived the part.”

Douglas said that in the 1970 production, “the Charleston crowd went wild” during the marketplace scene where a character called the Strawberry Woman sings about her goods.

archival footage of that, that was real,” Douglas said.

“People built their legacies off of that. And so the local cast, they knew how to bring to life the honor in that. My interviewees, that’s their legacy. They have those relatives, and they went to college because of that work. So to them, I think it was about giving honor to those supporting characters, and to our Gullah language and history. For them, it was about honoring the unseen experience of these folks.”

tion, gentrification and more.”

She was planning to abandon the project until a conversation with her father, Charleston City Councilman Keith Waring, changed her perspective and ultimately her direction with the documentary.

“My dad didn’t want me to let the project go,” said Douglas. “I thought, ‘Why does my dad care about Porgy and Bess?’ ”

Her father sat her down and told her about seeing the 1970 production back when he was a teenager. He explained to his daughter he remembered feeling a “real communal sense of pride” connected to that first-ever Charleston production, which was performed by a local cast.

It was produced by the Charleston Symphony Association, with Ella Gerber from New York City as director. James Edwards, the leader of the local Choraliers Music Club, served as choral director. They sold out 16 shows with tickets at $3, $4 and $5, and ended up netting a whopping $35,000, Douglas said. “Black people were not supposed to be the breakout sensation of the Charleston tricentennial celebration.”

After speaking with her father, Douglas decided she needed to instead focus the documentary on the 1970 production.

“I learned about the how and the why of the 1970 production, the fact that it had played all over the world and all over the country, how it was sponsored by the state department to prove that race relations were good in America, and yet, it never played in Charleston until this production,” Douglas said.

“I think Charleston should know that story.”

“There were Black folk in Charleston, walking around the streets, singing about their goods they’re selling — there's

Douglas said that though there is not yet a set release date, she hopes to complete her documentary by 2024. Her hope is that viewers of When Porgy Came Home walk away looking at Charleston differently, at Porgy and Bess differently, and at Gullah-Geechee culture in a more honorable way.

“My hope is that people aren’t as afraid to talk about race. That's my hope.”

Charleston leader Paul Stoney believes in the importance of having strong independent voices in journalism to challenge the status quo, strengthen democratic institutions and spread news that connects people to their communities.

“Independent newspapers like the Charleston City Paper prove they are committed to building inclusive, dynamic communities by publishing stories like those in this magazine that outline the historic importance of the new International African American Museum. Support South Carolina’s independent journalists with a gift today.”

Charleston played a fundamental role in the formation of American jazz music, yet the story is not often told in the same breath as New Orleans, Chicago or New York. In this story, Holy City jazz musicians and industry professionals illustrate the importance of our city’s contribution to the genre throughout the 20th century.

The story of Charleston jazz could not have been written without the Rev. Daniel Joseph Jenkins, a Charleston Baptist minister who opened Jenkins Orphanage in 1891.

“Three years later, [Jenkins] created a fundraising machine with the Jenkins Orphanage Band [program] that trained orphans to play musical instruments while raising money for the orphanage,” said College of Charleston (CofC) arts management professor emerita Karen Chandler, who is co-principal of the college’s Charleston Jazz Initiative program in partnership

continued on page 32

with the Avery Research Center.

“The [Jenkins musicians] played for President [William Howard] Taft’s inauguration in 1909 and were in the orchestra pits for many of the new Black Broadway shows that were opening in the early 1900s,” she said.

Jenkins’ students learned to capture the syncopated rhythms, intricate harmonies and improvisation that characterized early jazz. Jenkins, who was born into slavery in South Carolina around 1862, is not as well-known in U.S. history as Black empowerment pioneer Booker T. Washington, but Chandler said some historians recognize Jenkins for his social contributions to uplift Blacks in America as much as they do for Washington and civil rights activist W.E.B. DuBois.

“Jenkins was so successful that he had a Charleston and Harlem office, and his bands toured with a manager, a valet and cooks,” she said. “His obituary was published in The New York Times and his funeral in Charleston drew nearly 2,000 people.”

Jenkins Orphanage is known as the starting place of some of Charleston’s well-known jazz forerunners of the early 20th century. Now called the Jenkins Institute for Children, its 132-year legacy as a refuge for the youth remains strong.

Lowcountry musicians are “the main characters in a seminal American jazz story that’s yet to be fully told,” Chandler

Bertha “Chippie” Hill (right) was a blues and vaudeville singer and dancer born in 1905 in Charleston

and other musicians from right here on our Gullah Geechee soil of Charleston and the South Carolina Lowcountry contributed mightily to the development of jazz in America and in Europe. Charleston’s jazz story is an American jazz story.”

To shed light on Charleston’s role in cultivating and innovating jazz music means recognizing the city’s heritage of oppression, Beylotte said. The new International African American Museum, for example, overlooks the wharf where an estimated 40% of enslaved Africans entered North America, she said, referring to the transAtlantic slave trade from the late 17th to early 19th century.

“The foundational elements of jazz music were brought here by enslaved Africans,” she said, “and they influenced the rest of the people here, essentially creating what’s now known as blues and jazz. They infused the community with their culture, including their music and their rhythm. You can't argue with that — that makes Charleston an instrumental player in the formation of jazz.”

Laws and societal restrictions in 19th century Charleston prevented Blacks from being able to congregate and define their own culture as much as was possible in New Orleans, said Quiana Parler, acclaimed vocalist for Grammy Awardwinning Gullah ensemble Ranky Tanky. She said the vestiges of Spanish and French colonization in 19th century New Orleans gave greater opportunity to Black musicians to cultivate jazz performance than the social climate in the Lowcountry.

“New Orleans was a racist and slaveowning society also, but Charleston's history was far more conservative than New Orleans, and the rules in Charleston restricted Blacks way more,” Parler said.

said. There was Charleston-born singer and bandleader Bertha “Chippie” Hill, who can be heard on 1920s recordings with Louis Armstrong; and Edisto Island native James Jamerson, the innovative bass player for singer Pearl Bailey and then the pre-’60s Motown studio band Funk Brothers behind many famous hits; and Charleston-born rhythm guitarist Freedie Green who played in the Count Basie Orchestra for over 50 years.

“Count Basie hired Freddie and used to say that his playing was pivotal in maintaining that swingin’ pulse that defined the Swing Era,” Chandler added. “The little-known careers of these

Legendary Charleston saxophonist/clarinetist Lonnie Hamilton III, 95, has spent his lifetime immersed in performance and music education. He has lived the life of a Charleston jazzman.

Hamilton said when he thinks of Lowcountry jazz figures, “most times, they have been neglected. No one has taken much time to be with them and talk to them about jazz itself. And many times, you get the history verbally from some other musician as to what

‘Charleston’s jazz story is an American jazz story’

November 2, 2023

The Charleston Gaillard Center is thrilled to celebrate the opening of the International African American Museum with our partners. We have enjoyed working together with the IAAM team on many projects including Dance Theatre of Harlem in October 2022, and we are excited to continue collaborating on future productions like Step Afrika!’s Drumfolk on November 2, 2023. We stand with you on your journey to illuminate, inspire, and move people to action. Bravo!

happened with them.”

Before Hamilton graduated Burke High School in 1947 he said he had played all around Folly Beach and the Charleston area with a local ensemble called William Lewis Gaillard and the Royal Sultans and toured with the Jenkins Orphanage Bands.

“During those days being a Black person, hell, you didn't get in the paper … In the early days when I played with William Lewis Gaillard, nothing would be published about you then.”

After his college years, he ended up taking up a 20-year post as bandleader for Bonds-Wilson High School in North Charleston from 1955 to 1975. He said the Bonds-Wilson band was known up and down the coast under his leadership. Hamilton dived into cultivating the Charleston jazz scene in the early 1980s with his jazz club Lonnie’s on Market Street downtown, before taking up a residency from 1987 to 1996 at Henry’s On The Market during which he established the well-known act, Lonnie Hamilton and the Diplomats. The Diplomats were active in the late 1990s and up to the pandemic, performing consistently in Charleston’s Spoleto Festival USA and opening for international jazz acts such as Dizzy Gillepsie — also a South Carolina native.

that the Blacks were doing then, in order to use for his own for his own composition.”

Virtuoso saxophonist and pianist Oscar Rivers Jr. was born in 1940 downtown on Richmond Street. He was playing saxophone in a 12- to 15-piece jazz orchestra called Carolina Thumpers by the time he turned 15, and went on to graduate Burke High School in 1957. His classmate Joey Morant, the late world-class trumpeter, performed with the Carolina Thumpers. “He taught me how to play jazz,” Rivers said of Morant, who also played with the Jenkins Orphanage Bands.

“Jazz music is improvisational — it’s a gift,” Rivers said. “You cannot play what you cannot hear. By listening to records when I was in high school by the great alto saxophonist Charlie Parker, I was able to emulate the style of playing called Be-Bop, which originated in the early ’40s with Dizzy Gillepsie.”

Rivers left Charleston for decades to pursue higher education, studying the piano extensively in Chicago, Mexico and South America before returning in the 1980s. He played keys with Lonnie Hamilton and the Diplomats on and off for nine years. He formed his own group Rivers & Company in the early ’80s with his late wife, jazz vocalist Fabian Rivers. Their band played 10 concerts in South America as part of the International Music Festival in 1988.

Rivers played in ensembles at the Moulin Rouge in the 1950s, Touch of Class in the 1980s and Topside Lounge on Kiawah Island in the 1990s.

Currently, the Oscar Rivers Jazz Quartet plays with vocalist Kat Keturah at Hotel Indigo on Mount Pleasant on Saturdays.

trumpeter Cat Anderson, who also lived and learned to play at the orphanage, performed in stints with the Duke Ellington Orchestra from the 1940s to the 1970s.

Vocalist Elise Testone started singing in the Charleston jazz scene back in 2006.

“What stands out in my mind,” she said, “is hearing the soft yet intentional drum stylings of Quentin Baxter or Ron Wiltrout; the guitar tone of Lee Barbour as he played his own unique interpretations of old favorites — while Mark Sterbank or Robert Lewis soars through the song on saxophone over an upright bass played by Kevin Hamilton or Jeremy Wolf; and Gerald Gregory playing through his entire soul on a beautiful grand piano.”

Testone said she remembers how vocalist/instrumentalist Leah Suárez and the late journalist Jack McCray, founders of Jazz Artists of Charleston (JAC) nonprofit, worked tirelessly to sustain the city’s jazz culture throughout the early 2000s. “Their impact remains a staple in the community,” she added.

Oscar Rivers, 83, still performs regularly at Hotel Indigo in Mount Pleasant with vocalist Kat Keturah as Oscar Rivers and Company

“From the early days, you had what they then called ‘New Orleans jazz’ — but the Charleston people were doing their own thing. And they considered themselves to be the historians for jazz, because when George Gershwin came to Charleston, [he] used to hang out in the Black community. And [he] copied a lot of the things

“A lot of great musicians came out of Charleston that people don't even know about,” Rivers said. Georgia-born trumpeter Jabbo Smith, who lived and learned to play at the Jenkins Orphanage, gained notoriety in New York City in the 1920s playing alongside big name musicians such as Fats Waller and James P. Johnson. Greenville-born jazz

JAC and its community partners solidified the organization’s rebranding to Charleston Jazz in 2017, which encompasses Charleston Jazz Orchestra founded in 2008, Charleston Jazz Festival launched in 2015 and Charleston Jazz Academy established in 2017.

“Charleston has every right to claim a part [in] the creation of what we know of as jazz,” said acclaimed trumpeter and Awendaw native Charlton Singleton. “I wish that all Charlestonians would have the same vigor for that [claim] as our brothers and sisters in New Orleans and Savannah have for their part in the creation and advancement of jazz.”

When West Africans were shipped to the Americas, especially the South, they brought many ingredients, crops and techniques that are still eaten and used to this day as reflected in the Lowcountry’s Gullah Geechee culture and cuisine. Traditions and techniques were passed down through generations to keep their roots alive, despite an ocean and several centuries of oppression keeping them away from home.

“When I talk about food of [the Lowcountry], I always, always have to give a nod to the influences that have come from Africa,” said Kevin Mitchell, a historian and scholar of historical foodways of the American South. He also is a celebrated chef and instructor at Trident Technical College’s culinary program. Through the centuries, early African American culture has evolved into Gullah Geechee, an integral part of Lowcountry and Southern cooking that

strongly influenced American tastes. “Gullah cuisine is the Queen Mother of Lowcountry food,” said chef Benjamin “BJ” Dennis of Bluffton, South Carolina, a personal chef and caterer who specializes in Gullah Geechee cuisine. “You can't have a Lowcountry period without Gullah culture.”

And these traditions brought to the Americas centuries ago are still seen throughout modern day West Africa, according to chef Bintou N’Daw, owner

of African cuisine Bintü’s Atelier opening soon on Line Street in Charleston. N’Daw is a Senegalese native who moved to the United States 10 years ago and to Charleston two years ago.

“To me, Black food [in America] was soul food,” she said. “And then I discovered Gullah Geechee and Black food are really the roots of African food. They used not only the same method, but they kept that same method alive.”

The ingredients that have withstood time in the Lowcountry are a large part of the region’s culinary culture, and something seen in many dishes across menus and throughout the country.

“We always talk about how Native American influence is corn, cornbread, things like that,” Mitchell said. “[But] the ingredients [from Africa] have had a huge impact on how we eat and what we eat in this area.”

Ingredients like watermelon, benne seeds, black-eyed peas, okra and rice are some of the biggest imports slaves brought to the Americas, according to Dennis.

“I just think about the impact of enslaved people growing food here in this country, whether it was things that were brought with them on that travel to America,” he added. “Africans and African Americans have always had a huge impact on farming because they

actually grow the food that we eat.”

Thanks to similar climates and coastal regions, enslaved Africans were able to bring with them native African produce and crops, and had the advantage of doing so by tending the land of the Lowcountry.

According to David Shields, a professor at the University of South Carolina and specialist in Southern cuisine history, other foods from West Africa that came to the Lowcountry have since left and became part of other regional cuisine cultures.

“There’s an eggplant, originally called a guinea squash,” Shields said. “It was a red eggplant that was once grown throughout the South and now survives basically in Brazil. It looks like a tomato, but it's actually an eggplant, and a little on the bitter side.”

The last known Southern strain of this, according to Shields, was at a seed

continued on page 38

Gullah candies are desserts that many people don’t know about but have been passed down through generations, according to Charleston area baker Christina Miller. Miller owns Bert & T’s Desserts, a pop-up which specializes in Gullah desserts and pastries from recipes passed down from her grandmothers.

Miller said the African American women who sell flowers out of sweetgrass baskets downtown were also known as “Candy Ladies.” One of the candies sold were groundnut cakes, using an African runner peanut, a small peanut from Africa. The peanuts were crushed and cooked with molasses to form a hard candy. Another was called coconut cake or “monkey meat.”

“It’s the same deal as the groundnut cake,” Miller said. “But instead of peanuts, it was crushed coconut mixed in with the molasses to create a hard candy.”

Other candies and snacks included a benne brittle, made in the same manner as the former two candies, and candies with black walnuts.

At an event earlier this year in Gadsdenboro Park in Charleston, Bert & T’s sold the lesser-known Gullah candies and found much excitement from patrons, Miller said.

“It was really exciting to see folks know what it is,” she said. “One guy was like, ‘Oh my God, my grandmother used to make this!’ And it was just really cool to have people be like, ‘I haven't seen this in forever’ and things like that.”

house in Louisiana that burned down over a decade ago.

It wasn’t just ingredients that were brought to the Americas, either. Cooking techniques in Gullah Geechee culture have remained close to ancestral roots of West Africa.

“Traditional [Gullah Geechee] red rice is exactly how we cook it in West Africa,” N’Daw said. “We’ll cook whatever vegetables, onions, then we add tomato paste and cook it for a long time, and then we add rice and whatever else we want.”

For someone like chef Darren Campbell, author of Charleston's Gullah Recipes and owner of spice brand Palmetto Blend, those techniques were passed down through the generations.

“It's the same kind of techniques that we used back in the day,” Campbell said. “The same techniques that [my great grandmother] used, my grandmother used and my mother used, and my mother passed to me. Those were the same techniques that my great grandmother, her parents also used, and it passed down from generation to generation.”

One of the dishes Campbell specializes in — and adores making — is red rice, he said. It’s a dish that connected him to his grandmother and his Charleston roots when he moved away to Atlanta.

“It was always my favorite growing up,” he said. “But I never knew how to make it. So, I called my grandmother and I had some trouble at first, but after I figured out the perfect recipe, it became one of my favorite dishes to cook.”

While some of the traditions and ingredients have been passed down, there also have been many adaptations through the centuries to accommodate what’s available in the area.

N’Daw said that while the weather in the Lowcountry is very similar to West Africa, enslaved Africans still had to make some adjustments to meals. For example, in the Lowcountry, greens usually consist of collards, but West African cuisine would use more exotic greens like cassava leaves.

“We had a lot of ways of cooking that are exactly the same as back home,”

N’Daw said. “So when Africans were enslaved, they just started cooking for

the people they were enslaved to and bringing a different way of cooking. So it becomes a little bit incorporated in American food from the South.”

Their transfer to America also added different proteins to their diets.

“Most of West Africa is Muslim, so pork is not popular in Africa,” N’Daw said. “It’s something that you won’t find in many places. We eat a lot of goats, a lot of lambs and a lot of fish. And we don’t fry much stuff, either.”

But when in America, hogs and chickens were introduced into the diet of enslaved Africans, according to Mitchell.

“We know that prior to coming here, most of the African diet was more plantbased,” Mitchell added. “Of course, when they were brought here they were introduced to meat, specifically pork. If you're talking specifically about soul food, or even Southern food, you know, you're always going to talk about pork, but if you’re talking about the Lowcountry, then you're always going to talk about seafood, specifically catfish.”

AT&T Attorney Gary A. Ling

Beemok Hospitality Collection

Bell Legal Group

Blackbaud

The Boeing Company

Charleston Metro Chamber of Commerce

Charleston County Parks and Recreation

Charleston Gaillard Center

Charleston School of Law

Charleston Southern University

City of Charleston

Dominion Energy

Gibbes Museum of Art

The InterTech Group

Joye Law Firm

Nephron Pharmaceuticals Corporation

Santee Cooper

South Carolina Aquarium

University of South Carolina Press

The Civil War ended for Charleston when the Black Union regiment, the Massachusetts 55th, entered that city in February 1865. While Whites, who largely supported the Confederacy,

mostly fled Charleston, African Americans celebrated in the streets, cheering the Black troops as liberators.

The effects of the war left the city in ruins, but African Americans were optimistic about the future. Schools such as the Avery Institute were established, and many looked forward to a promise of equality. President Andrew Johnson, who replaced the assassinated Abraham Lincoln as president, pursued a lax policy of Reconstruction of the Southern states. He allowed them to enact “Black Codes” restricting the movement and freedom of the formerly enslaved, breaking the promises of equality.

In November 1865, 52 Black delegates met in Charleston’s Zion Church to formulate a position regarding their future in the post-emancipation South. Their address invoked the lan-

guage of the Declaration of Independence to claim full rights of citizenship for themselves and demanded the end of the “Black Codes.”

In 1867, the “Radical Republicans” in the United States Congress embarked on a program to transform the defeated Southern states after the Civil War. Part of this transformation involved the changes in the status of African Americans in these states. Defying (and later impeaching) Johnson for opposing such reforms, congressmen such as Charles Sumner of Massachusetts and Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania called for the disfranchisement of some Confederates, federal troops to be placed in the Southern states, and for the right of Black men and poor Whites to vote.

The freedmen quickly moved to take advantage of their

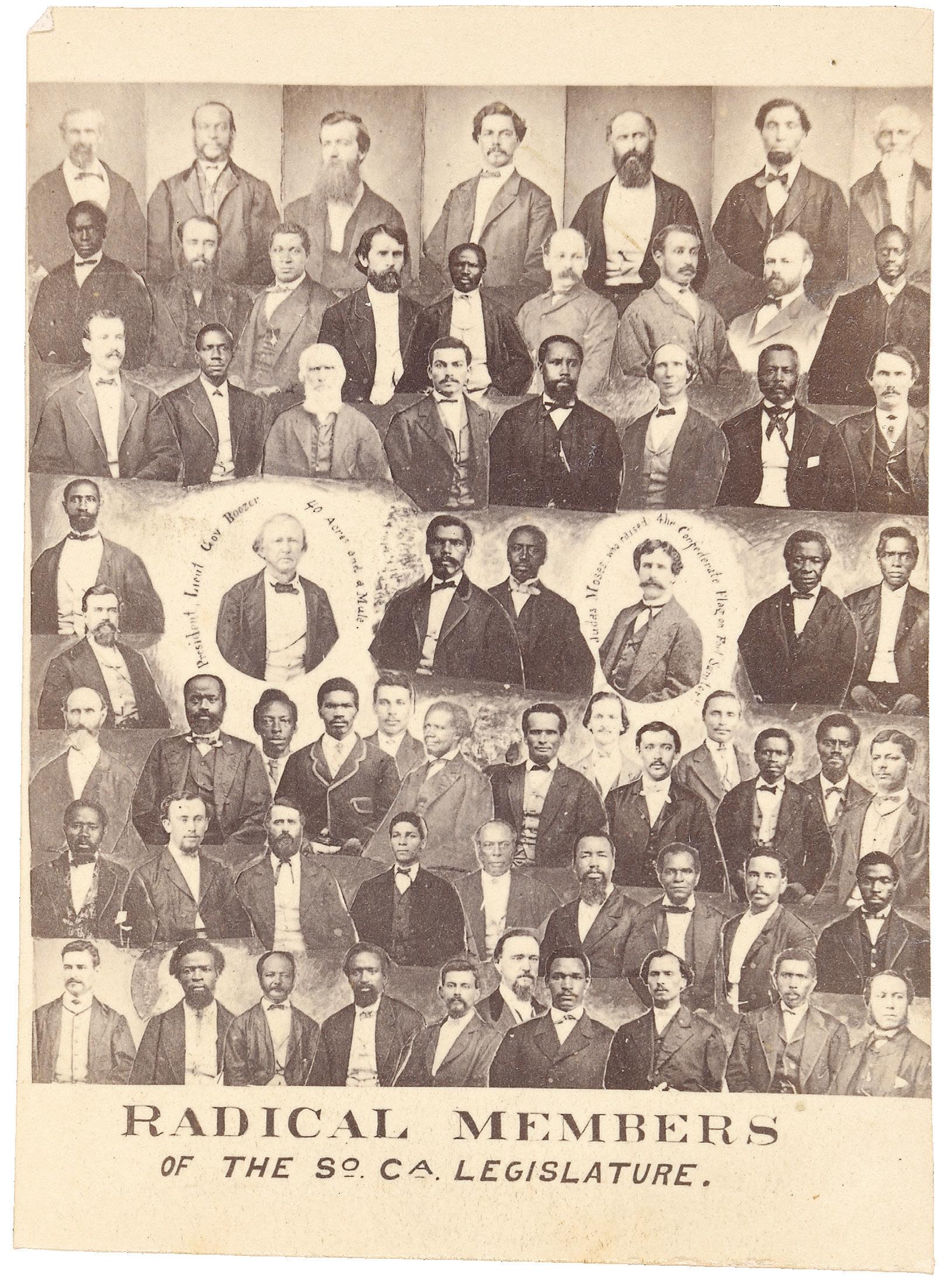

A carte-de-visite of 64 so-called “Radical” members of the reconstructed South Carolina legislature after the Civil War

The period after enslavement and the fall of the Confederacy was one of hope for African Americans, particularly in South Carolina.

new opportunities. From January to April 1868, 76 Black delegates (twothirds of whom were formerly enslaved) and 48 White delegates met at the Charleston Club House on Meeting Street to compose a new Constitution for South Carolina.

Miracles unimagined a few years earlier took place after this meeting. This interracial coalition called for laws discriminating against Blacks to be stricken from the Constitution. State hospitals and mental institutions were established. On Jan. 23, 1868, Robert Smalls, who six years earlier freed himself and his family from slavery by sailing them aboard the Confederate ship The Planter, called for the establishment of a public school system of South Carolina. During the following 12 years, the University of South Carolina became the only desegregated school in the Deep South and two Black men, Alonzo J. Ransier and Richard H. Gleaves, served as lieutenant governor. Some 315 Black South Carolinians held political office.

It was a time of hope. But White Southern leaders led a violent uprising against these developments through groups such as the Ku Klux Klan and the Red Shirts. The murders and lawlessness that resulted led to the Hayes-Tilden Compromise of 1877 that ended Reconstruction. Meanwhile, the Daughters of the Confederacy would edit out the positive results of Reconstruction from the history books used in schools, which is why such facts are not common knowledge today.

The progressive state Constitution of 1868, which granted equity among Blacks and poor Whites in South Carolina, was scuttled when U.S. Sen. “Pitchfork” Ben Tillman, who had earlier served as governor, called for a convention to rework the state Constitution. In 1876, he was among the mob who massacred Blacks at Hamburg, South Carolina. He rose to power in the 1880s preaching a fair deal for the state’s poor White farmers and intense race hatred. As governor of South Carolina in 1893, he turned over an African American named John Peterson to a lynch mob in Denmark, South Carolina. After narrowly winning his bid for the United States Senate in 1894, he felt that a divided White vote and united Black vote nearly caused him to lose. He planned to disenfranchise South Carolina’s Black population without openly violating the 15th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which was passed in 1870 and guaranteed the right to vote regardless of race.

A wood engraving of the 55th Massachusetts Colored Regiment singing “John Brown’s March” in the streets of Charleston in the March 18, 1865 edition of Harper’s Weekly

The 1895 S.C. Constitutional Convention became the major setback for African American progress. A constitutional convention proceeded at the Statehouse in Columbia to overhaul the 1868 state Constitution.

It is not widely known that six leaders tried to stop Tillman’s plans. Robert Smalls and William J. Whipper, who were part of the 1868 convention, James Wigg and Isaiah Reed, two Black lawyers from Beaufort, Thomas Miller, the founding president of South Carolina State College, and Robert Anderson, a

Black teacher from Georgetown went to the Statehouse to boldly argue against the proposed Constitution. They lost 166 to seven, but their loss would plant the seeds for the civil rights movement in South Carolina that was to come.

Fordham is a Charleston author, lecturer and adjunct professor of history. The History Press recently published his book, The 1895 Segregation Fight in South Carolina. You can purchase it online for $21.99.

The effects of the war left the city in ruins, but African Americans were optimistic about the future. Schools such as the Avery Institute were established, and many looked forward to a promise of equality.

The International African American Museum seeks to tell and share the stories of thousands of enslaved Africans and their families who worked on plantations and in towns to build the South’s agrarian economy. Here are some stories from the past and present that you’ll find in the museum.

(1767-1822), carpenter, insurrectionist

Vesey, born on the Caribbean island of St. Thomas, lived on King Street in Charleston with Joseph Vesey, a ship chandler, and his family. Joseph Vesey purchased Denmark when he was 14. Denmark Vesey was literate and multilingual which helped him to succeed at his job dealing with imports and exports. Vesey bought his freedom in 1799 after he won the lottery and lived on Bull Street with his second wife, Susan. Black people, free and enslaved, faced hostility in the city, but the closing of the African Methodist Episcopal Church was the tipping point, according to the S.C. Encyclopedia. Vesey reportedly wanted to lead Black people out of the hostile environment, but the mayor, James Hamilton, and governor, Thomas Bennett, got word of his plans for a violent revolt. Vesey was arrested, tried and found guilty. He was sentenced to hang along with five others. More than 130 Black residents, free and enslaved, were arrested. Thirty-five were hanged while 37 others were exiled to Cuba. The AME Church was shut down until Vesey’s son, Robert, helped rebuild it after the Civil War. A statue of Vesey today is in Hampton Park.

Richard Cain

(1825-1887), minister, abolitionist, politician

Richard Harvey Cain was born in 1825 in Greenbrier County, Virginia. By age 19, he was licensed to preach in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) denomination. In his late 20s, Cain became a prominent abolitionist, working with Frederick Douglas and Martin Delaney. He was transferred to Charleston after the Civil War with the task of building a church. Emanuel AME Church was built on Calhoun Street and gained more than 2,000 members within its first year. Cain also is believed to be the first Black newspaper editor after he purchased the South Carolina Leader in 1866 and changed its name to the Missionary Record. Cain served in the S.C. Senate (1868-1870) and twice in the U.S. Congress (1873-1875, 1877-1879). He famously stated, “All we ask is equal laws, equal legislation and equal rights.”

Jonathan Jasper Wright’s formerly enslaved parents found freedom in Ithaca, New York, where he was born in 1840. Wright moved to Beaufort, South Carolina, in 1865 to teach Black federal soldiers and formerly enslaved people. He briefly returned to Pennsylvania to become that state’s first Black attorney. He later became the first Black attorney in South Carolina. After losing an 1868 lieutenant governor’s race, Wright returned to politics to win a seat in the South Carolina Senate. When a vacancy opened in South Carolina Supreme Court in 1870, Wright became the court’s first Black jurist. The Charleston Daily News stated that Wright had “the highest position held by a colored man in the United States.” After resigning in 1877 to dodge the threat of impeachment, Wright opened a law firm at 84 Queen St. in Charleston where he taught law as chairman of the law department at Claflin College.

Robert Smalls was born to an enslaved house servant in Beaufort, South Carolina. At a young age, Smalls became a ship rigger and sailor on coastal vessels. Smalls rose to stardom in the Union Navy after he commandeered the Planter, a Confederate boat, and turned it over to Union. He served in the Civil War, eventually receiving a promotion to captain, making Smalls the first Black man to command a ship in the U.S. military. During his three years as captain of the Planter, Smalls was involved in 17 war-time engagements. After the war, Smalls returned to Beaufort and purchased his childhood home. As a hero, he became an influential political leader, becoming a core founder of the state’s Republican Party. During Reconstruction, Smalls served in the state House of Representatives and the state Senate. In 1874 Smalls was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. “My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be equal of any people anywhere,” Smalls once remarked. His early efforts immortalize him as a key factor in the progression of civil rights.

(1898-1987),

Septima Poinsette Clark was born in 1898 in Charleston, the second of eight children, to parents who prepared her to be a social justice crusader. Clark began her teaching career in 1916 on Johns Island at the underfunded Promise Land School at a time when Black teachers were barred from Charleston County public school classrooms. Clark fought this state law alongside former congressman Thomas E. Miller. She was a member of several organizations including the National Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Clark was later asked to denounce her NAACP membership. When she refused, she was fired. “I have a great belief in the fact that whenever there is chaos, it creates wonderful thinking. I consider chaos a gift. I just tried to create a little chaos.” Clark is credited as a founder of a citizenship school with Esau Jenkins to promote literary and political literacy. It served as a model for voter registration across the South for Black people. The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. called Clark the “Mother of the Movement” after their collaboration during the civil rights movement.

(1899-1990),

Maude Callen was born in 1899 in Quincy, Florida. She received her bachelor’s degree from Florida A&M College and she studied nursing at Tuskegee Institute. In 1923, she began her nursing career in Berkeley County as a missionary with the Protestant Episcopal Church. Callen taught children how to read and write and administered vaccinations at local schools. Known for her work as a midwife, Callen helped deliver more than 1,000 babies during her lifetime and provided pre- and post-natal care. She started a lecture series and two-week program to educate women on midwifery. Callen was hired as a public health nurse to supervise midwives when the Social Security Act was enacted in 1935. She worked in the Division of Maternal and Child Health for about 30 years before her retirement in 1971. Before she died in 1990, Callen was inducted into the South Carolina Hall of Fame.

Esau Jenkins was born in 1910 on Johns Island. He was forced to stop his education in the fourth grade to help his family financially. Jenkins valued education and its accessibility to children. Doing whatever he could to help, he drove Black children on the island to their public schools. In 1945, he started to bus students across the Charleston area. To continue his mission, Jenkins established the Progressive Club, teaching adults the importance of their right to vote and to keep them informed so they can uphold their civic responsibilities. The citizenship school, founded by Jenkins and Septima P. Clark, helped Black adults become literate and register to vote. According to his family, his motto was, “Love is progress; hate is expensive.” A Volkswagen van with that painted on it is in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American Historic and Culture in Washington, D.C.

U.S. Rep. James E. Clyburn was born in Sumter, South Carolina. He received his bachelor’s degree from what is now S.C. State University. Clyburn has a long career in public service, starting in 1962 when he was a teacher, employment counselor and youth and community leader for nearly a decade. He entered the political realm as a member of S.C. Gov. John C. West’s staff in 1974 and was eventually promoted to become South Carolina’s human affairs commissioner. Clyburn won his first election in 1992, becoming the state’s first Black congressman since 1897. One of Clyburn’s priorities is educational equity. “Education is the great equalizer and shouldn’t be limited to the wealthiest few,” he said. In 1988, he was elected chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC). Clyburn was re-elected to Congress in 2022 to serve his 16th-consecutive term in the state’s Sixth Congressional District.

The Rev. Clementa Carlos “Clem” Pinckney, a native of Beaufort, South Carolina, was a member of the South Carolina Senate and pastor of Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in Charleston. Pinckney stepped into the pulpit at age 13 and five years later he was assigned his first church. Pinckney received degrees in public administration and divinity. He was pursuing a doctorate in ministry when a gunman on June 17, 2015, entered Emanuel AME Church, killing him and eight other members of the church. President Barack Obama delivered Pinckney’s eulogy on June 26, 2015, at the College of Charleston. Pinckney once said, “Our calling is not just within the walls of the congregation, but we are part of the life and community in which our condition resides.” Pinckney was well known for his intertwining of civil rights activism and policymaking with the gospel tradition, focusing on gun control and police reform.

Here is an artistic representation of human bondage of captured Africans on slave ships making the trans-Atlantic passage. You can see it on the ground level of the International African American Museum.

At AT&T, we believe connecting changes everything.

We are proud to support the International African American Museum as it connects people to the stories of the past and inspires a brighter future for all.

AT&T has been connecting South Carolina communities for nearly 145 years, and it remains our focus today. We are committed to doing our part to bring connectivity, and the economic opportunity that comes with it, to more South Carolinians.

Your Purpose is our mission at CSU.

Whether you are just starting out or finishing what you started, embark on an academic journey that will lead to a life of significance and purpose. You can choose from more than 60 undergraduate majors, more than 20 graduate degree programs, or two doctoral programs. If you need a flexible and affordable degree that fits into the busyness of life, check out our nationally-ranked Charleston Southern Online! Your educational journey will equip you with a biblical worldview, competencies to perform at the highest levels, godly character, and experience to grow your grit.

CLASSES START EVERY 7 WEEKS. WHAT ARE YOU WAITING FOR? LEARN MORE

Boeing is proud to partner with the International African American Museum to further its mission to explore and honor the untold stories of the African American journey. We look forward to celebrating the grand opening together. boeing.com/community