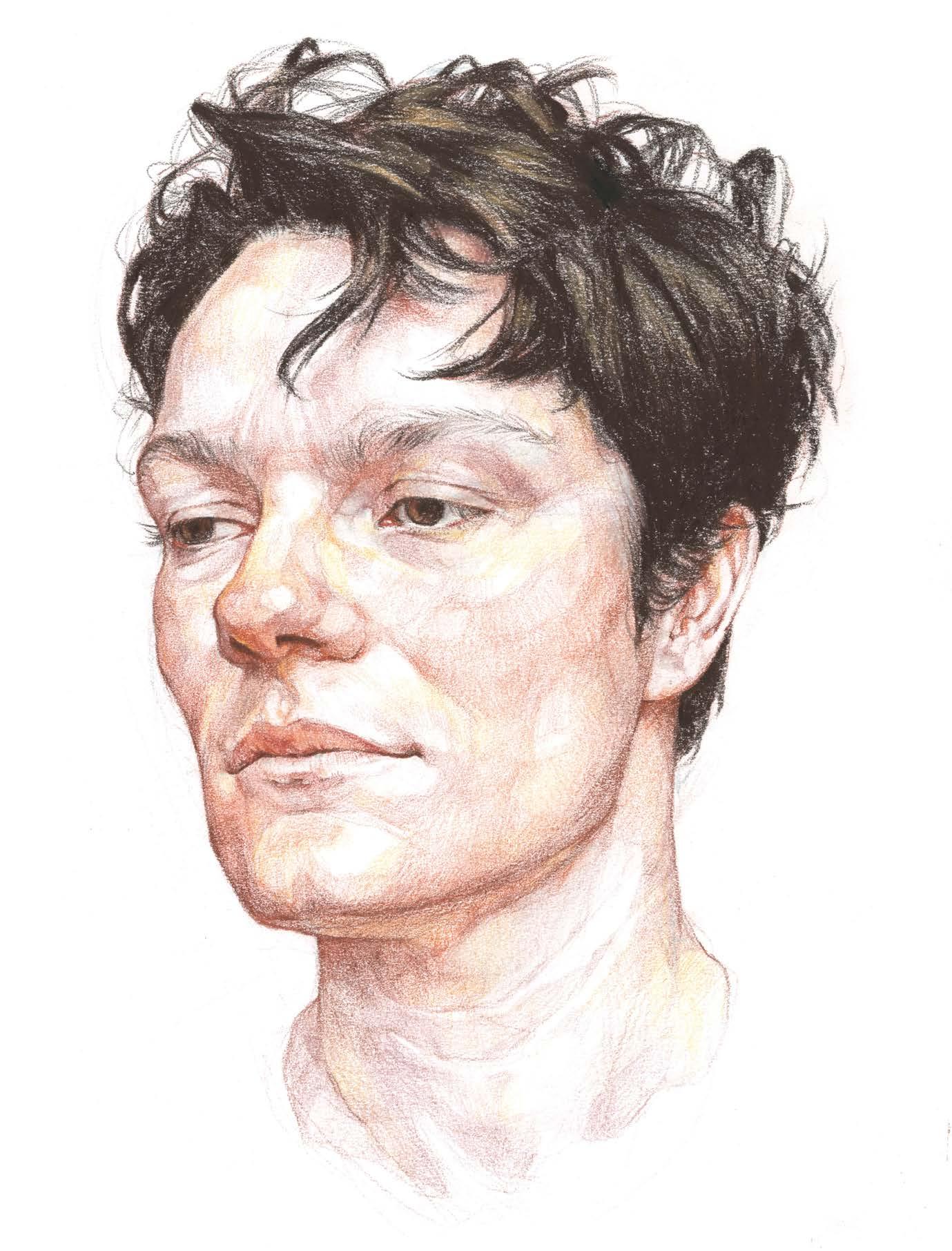

This Oxford-based artist blends both classical and contemporary influences, exploring identity and societal themes through narrative-driven paintings, says Sara Mumtaz

Toby Michael’s early life, among the neoclassical beauty of Buckinghamshire’s Stowe Gardens, shaped his understanding of aesthetics and human interaction with nature. This environment and his father’s role as a housemaster at Stowe School instilled in him an appreciation for art from a young age. “My early understanding of how humans interact with nature was heavily curated and predicated on the idea that aesthetics and beauty were important, even when devoid of practical utility. I grew up believing that human interaction with nature

was fundamentally good. It wasn’t until much later that I saw this was not the case in many places. Only as I have grown as an artist, have I understood that the beauty I witnessed held utility in its own right; it was psychological,” says Toby.

At 11, the artist moved city and enrolled in a state school, leaving behind the serene Stowe Gardens. Amidst teenage pursuits like football and video games, academic setbacks in GCSEs and A-levels initially steered him away from art. Returning to Stowe as a student was transformative. Despite initial doubts and gratitude towards his parents, Toby rekindled ▸

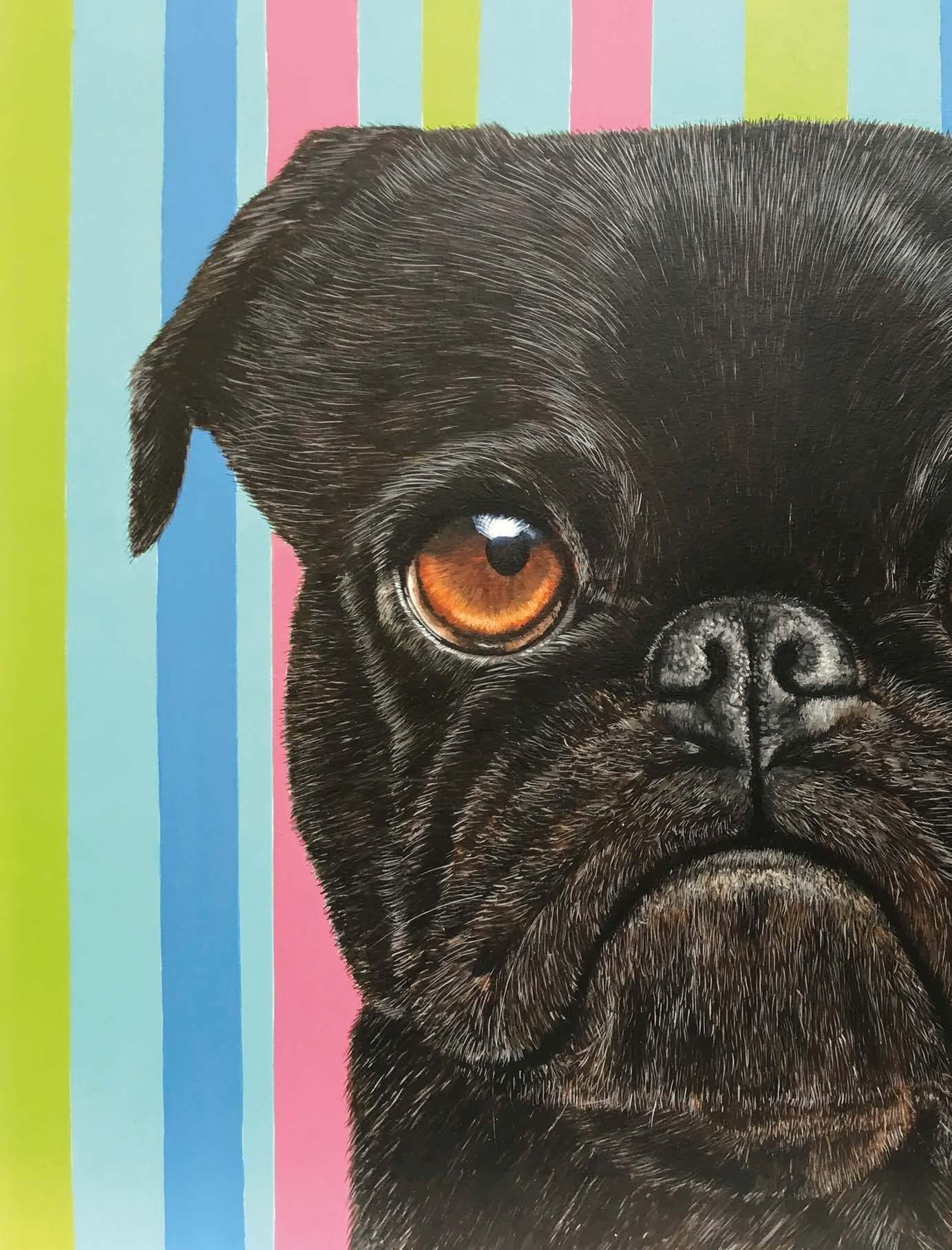

Having honed her craft working on large scale murals, JO GRAY tells Sarah Edghill how she discovered a love of pet portraits and developed her own inimitable style

After doing a foundation course in Art and Design at Nottingham Polytechnic, Jo was accepted into Central Saint Martins in 1990 and specialised in illustration. Like many artists, after graduating she found it daunting to have to make the transition into employment, and she trained and worked as a fitness instructor while building a portfolio of her work and looking for representation from illustration agencies. After a year in London, she moved back to Nottingham and worked alongside her mother in a painting and decorating business, honing her skills in paint effects such as rag rolling, stencilling and marbling. She also completed the occasional mural and, after her work was featured in a local paper, received a commission to paint the children’s areas in three health clubs, which were later acquired by David Lloyd Clubs. artistjogray.co.uk ▸

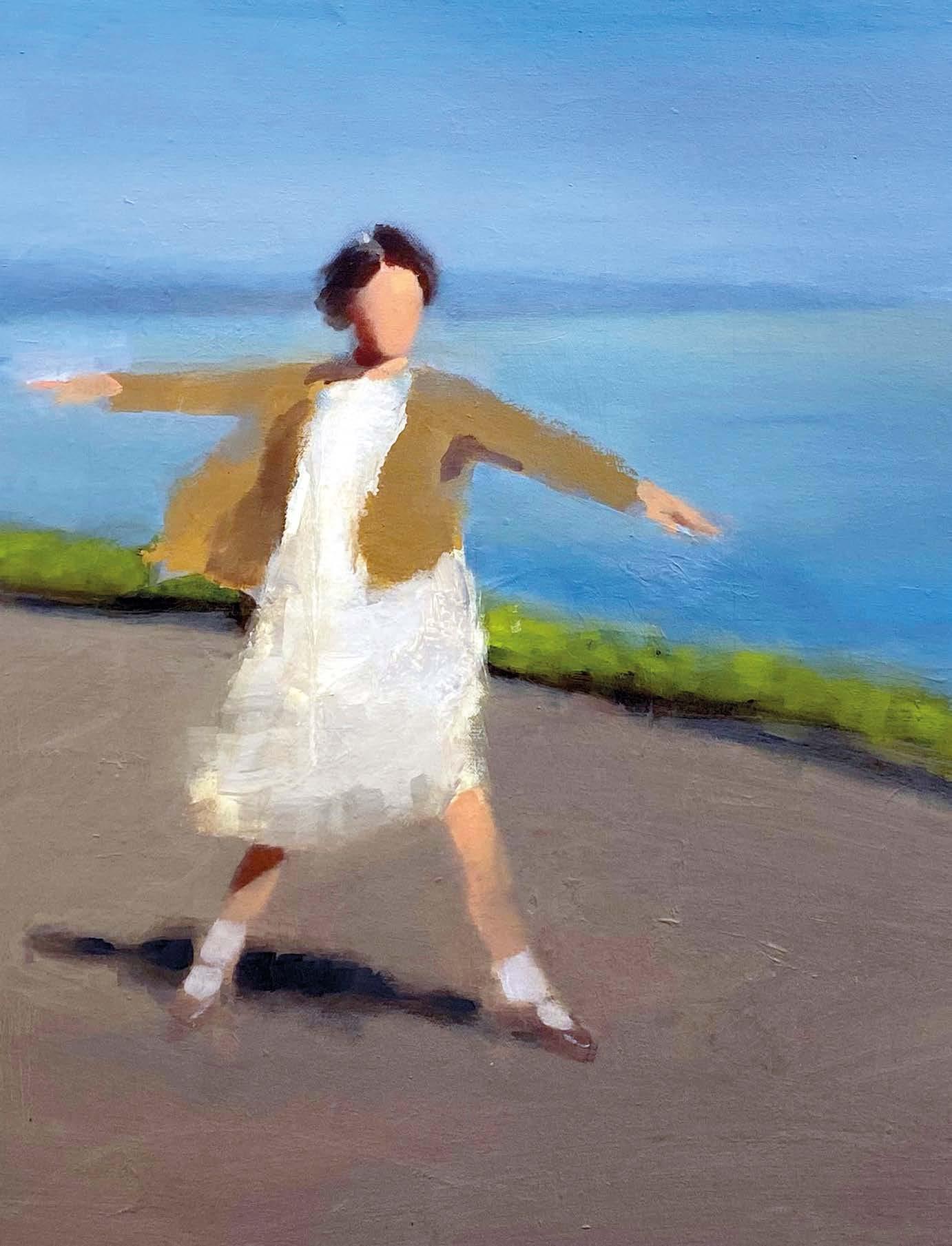

This artist breathes life into nostalgic mid-20th-century Britain through his eery, reminiscent paintings, says Ramsha Vistro

David Storey’s art journey is as captivating as the paintings he creates. Growing up amidst the atmospheric landscapes of Cumbria, his early experiences were steeped in a world of historical buildings and ever-present rain, which seem to have seeped into his evocative works. From an early age, David was surrounded by art and creativity, thanks to his father’s influence and the mentorship of an inspiring art master.

The artist’s approach is rooted in his fascination with what he calls ‘the edge of living memory.’ His (slightly haunting) works often evoke personal memories and emotions, drawing viewers into an almost otherworldly state where figures and scenes blur between the past and the present. This is no coincidence; David meticulously chooses images from his own archive, often reimagining them through a series of preparatory sketches before committing them to canvas. His use of unconventional tools like sponges and ▸

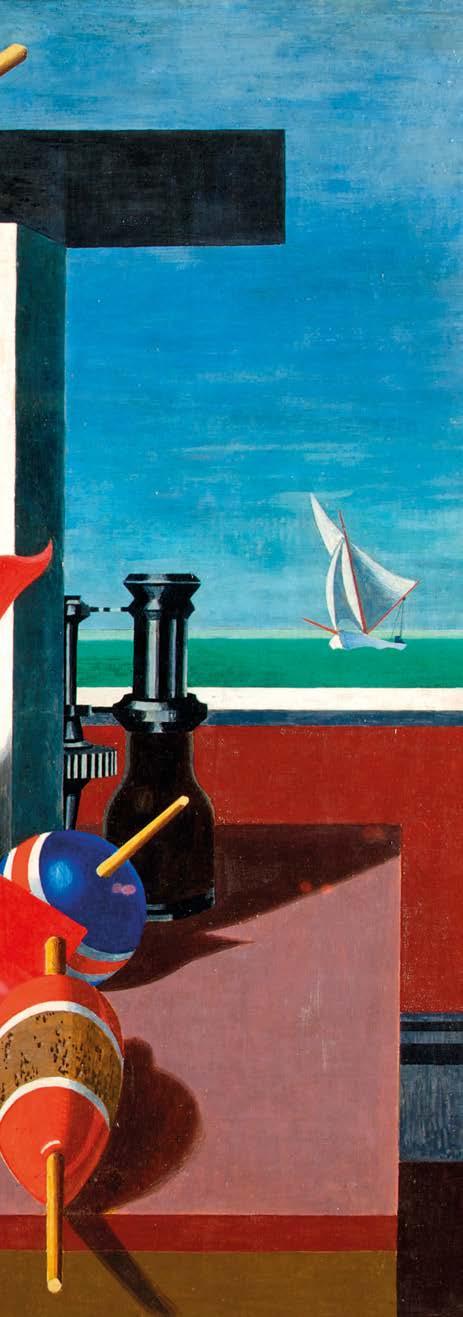

Still life was once seen as an inferior art form by the great and the good. A new exhibition seeks to debunk that myth, explains Amanda Hodges

In 1669, famous diarist Samuel Pepys wrote with palpable enthusiasm, “A Dutchman newly come over [to London] did show us a little flowerpot of his doing, the finest thing ever – the drops of Dew hanging on the leaves, so I was forced again and again to put my finger to it to feel whether my eyes were deceived or no. A better picture I never saw in my whole life, and it is worth going 20 miles to see.”

Pepys was referring to Simon Pietersz Verelst, one of the first artists to introduce the continental form of still life to Britain. In the Ancient World one finds Pliny’s early account of grapes painted so delectably and “so true to nature…birds came to peck at them,” but if seeking the genre’s real roots, then it’s

necessary to look back towards the Netherlands in the early 17th century where still life emerged as an independent form.

Interestingly, prior to 1650, there existed no term to describe the genre: apparently, artists simply referred to ‘bouquets and breakfast pieces’ or ‘flower, fruit and fish pieces’ to describe such work. The name’s origins derive from the Dutch; leven (life or nature) meant ‘model,’ ‘still’ conveyed ‘motionless.’

The Dutch influence may also owe much to the fact that after the 1688 Glorious Revolution, England was jointly ruled by Dutch-born King William III (Prince of Orange in the Netherlands) and his English wife Queen Mary, something which inevitably whetted the British appetite for Dutch art. ▸