The ketch Lutine of Helford was the first yacht built for Lloyd’s Yacht Club. Now restored, she lives on as a family racing yacht

How deep is your love? It’s a question Martlet must have pondered many times as she sat on the drive of Anne Roe’s house in Maidenhead, near the banks of the River Thames. For she had carried her owner in the morning sun, looked after her in the pouring rain and frolicked together in the summer breeze. But now, the 15ft (4.6m)dinghy was slowly sagging into her trailer, her once-vibrant hull splitting at the seams, apparently beyond repair. Would Anne be the light in her deepest, darkest hour, would she be her saviour when she fell – or would she simply walk away and consign the old boat to the bonfire?

In the end, the decision was put in the hands of Cornwall-based boatbuilder Ashley Butler. His verdict, when the boat was brought to him in 2017, was that the hull needed to be completely rebuilt. The idea of building a new hull for venerable old yachts, such as the great Fife and Nicholson classics, is something we’ve grown accustomed to. But a 15ft (4.6m) dinghy? Surely it would be cheaper just to buy a new boat? But that of course would be missing the point. This wasn’t just any old wooden dinghy. This was Martlet, the boat that Anne had learned to sail on and which was the repository of countless memories for her and her family over the previous 30 years.

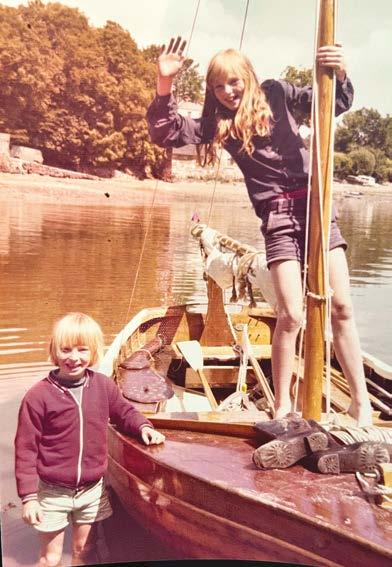

It all started when she was 10 years old. “One day, my brother and I came back from school and dad said, ‘I’ve bought a boat,’” Anne remembers. “We jumped up and down like little kids do, not really knowing what it meant. The next day the dinghy was on the drive. None of us could sail, but we’d all been brought up on Swallows and Amazons, so we wanted a boat like that. Dad learned to sail, and then taught my brother and me. He

was an accountant and didn’t know anything about boats, so it was just a romantic dream.”

Nothing was known about the boat’s history, apart from a builder’s plaque on the inside of the transom which read GA Feltham – Yacht & Launch Builder –Portsmouth. It was only while researching this article that I came across a brief mention on Martlet in the Emsworth Yacht Club history book. According to its author, she was designed by HJ Penrose (a noted aircraft designer and occasional designer of boats) in 1948 as a prototype for a possible new one-design class for the club. In trials, she was beaten by another boat, the “hard-to-beat” Betsy, and Martlet remained a rather lovely one-off.

For many years, Anne’s family rented a cottage in Helford village in Cornwall once or twice a year, taking Martlet down on a trailer, and spent many happy weeks messing around with her on the Helford River. It was a formative time. Anne remembers sailing to nearby Falmouth, five miles away, and having to row back home when the wind died. She remembers sailing up the river with her father, Bruce, and hearing the birds singing at the water’s edge as they rowed back down at dusk. She remembers breaking the boom fitting in a strong wind and being towed home by a friendly fisherman even though they knew perfectly well they could have made it safely to shore without him.

The one person who never liked the boat much was Anne’s mother Betty, who was knocked on the head by the boom the first time she went out and never sailed on her again –though she could occasionally be persuaded to go on board, if the outboard was fitted, for a trip to the Budock Vean Hotel on the other side of the Helford River for tea and scones with clotted cream.

Like England, Sweden is a country with many miles of coastline and a rich boating history. It is therefore not surprising that Sweden has been well supplied with good designers, boat builders and craftsmen. The geography and designers have also left their mark on the boats created here.

Roughly speaking, it can be said that the Swedish south and west coasts have produced more robust and relatively wider types of boats, while the east coast, with its sheltered archipelagos, has produced somewhat more slender vessels.

The Square Metre is probably the most famous example of a boat type designed for Swedish conditions. The rule came in 1908 and was an immediate success, partly in conflict with the then newly created international rule. Critics and supporters were divided according to the marine conditions, with the west coast, with its more open sea, becoming a stronghold for the R-rule and the Square Metres being celebrated on the east coast with more sheltered conditions. But economics also came into play and the R-boats were expensive to build, while the new Swedish rule initially made it possible to build fast, cheaper boats suitable for the archipelagos. Gradually, however, even the Square Metres became more extreme and more expensive to build. This in turn led to new Swedish boat types such as the Mälar Classes 15, 22, 25, 30, the Neptune Cruiser (both largely variations on the Square Metre concept) and the Folkboat, the result of a construction competition held by the Swedish Sailing Federation.

There are also several examples of refined traditional boat types such as the Koster (originating on the west coast) and the Snipa, both with a pointed

From the Baltic in the east to the North Sea in the west, Sweden has produced a rich array of yachts, with a revival scene today to match any other nation

WORDS AND PHOTOS STEFAN IWANOWSKIAnnual gathering in Skärhamn on the west coast Annual parade of classic boats at Heleneborgs Båtklubb in Stockholm

WORDS BRUNO CIANCI, PHOTOS BY BRUNO CIANCI & HAKAN GÜNEŞ

WORDS BRUNO CIANCI, PHOTOS BY BRUNO CIANCI & HAKAN GÜNEŞ

In June the yacht Gonca (pronounced ‘Gonja’) returned to what had been her home for over 20 years: the Rahmi M Koç Museum, founded in 1994 and named after its founder, common practice in Turkey. Koç, born in Ankara in 1930, is such an avid collector of objects related to the history of industry and navigation that he had to establish museums to gather them and make them available to all. CB readers may be familiar with a number of his other vessels: Romola, Lady Edith, Rosalie, Maid of Honour, and Gonca – to name a few – are all unique pieces. Out of practicality someone has rounded the Koç collection up to 50, but they almost certainly outnumber

Above: Gonca steaming off Tuzla for sea trials after her last restoration. The ship still relies on her steam engine

that. Gonca is one of the most fascinating, not least because her story is shrouded in a blanket of smoke –smoke produced by a triple-expansion engine.

Despite extensive research, the origins of Gonca remain a mystery. It will be difficult, in light of the available documents, to unlock the enigma. Her operational life since World War Two is all that is known; everything she experienced before is speculation. The most accredited theory has it that the ship – which is completely devoid of plates and hallmarks – was built in a British shipyard in the early 20th century. This may be deduced from certain

clues, the first of which is the presence of machinery of English manufacture; further clues concern the instrumentation and other parts also made in the UK. Some Turkish naval historians, referring to the Ottoman naval registers, believe that Gonca could be what was formerly called Selanik, a tug and support vessel used before 1912 in the port city of the same name (‘Selanik’ is Turkish for ‘Thessaloniki’), when the city was still under Ottoman rule. The superstructures of these two vessels clash, but the size and shape of the hulls is almost identical. With the outbreak of the First World War, the Ottoman navy would convert the ship into a minelayer, in which capacity she saw action during the legendary

defence of the Dardanelles in 1915. The question is: are the Selanik – whose fate is unknown – and Gonca the same ship? What we can state with certainty is that the ship we know today as Gonca was eventually laid up in the Gölcük naval base. Later she was used by the navy of the newly-established Republic of Turkey as a passenger ship under the name Konca. A sad period of abandonment followed, ending with the acquisition by the present owner through the Koç Foundation in 1989.

The technical project was conceived by Camper & Nicholsons, with interiors penned by Ken Freivokh Design. Freivokh, originally from California, but based in the UK for decades, was

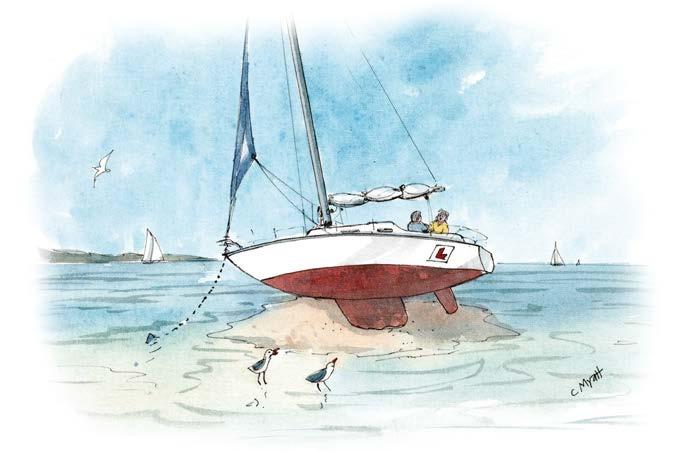

Sailing is by far the easiest part of sailing. For once you’ve allowed for deviation, variation, tide, leeway and innumerable other factors such as psychotic skippers like Captain Ahab and neurotic crew like Fletcher Christian, it is in theory possible that – by means of waggling the tiller to and fro and pulling in various ropes and letting them out again –you may, with a little luck, arrive at your destination or somewhere similar.

If on the other hand, and through no fault of your own, such as faulty dividers, a coffee stain on a chart, melting a plastic spatula while frying eggs, in other words doing exactly what you’ve been told to do, ie making breakfast, you end up being pounded to pieces at the foot of a 200ft cliff on a lee shore, all is not lost – unless it’s your own boat.

On the more positive side, ie if it’s someone else’s boat or better still a sea-school yacht, it will have all sorts of interesting equipment and gear on board that will allow you to gain valuable practical hands-on experience, such as: hitting red DSC buttons; making May Day calls; and firing colourful flares and rockets that go whizz and bang and make such lovely patterns in the sky you can’t help going “ooooh” and “aaaah” and “look at that one, isn’t it pretty?” Next comes “gosh” as your life-jacket inflates with a “poof,” followed by “oh,” if it immediately deflates again. The same applies to life rafts, and even more so if it actually stays inflated but someone has forgotten to tie the lanyard to the transom of the yacht. In these circumstances, having a sharp pocket knife at the ready is unlikely to restore your standing with your crewmates. Once you’ve run out of buttons to push and toggles to pull and used every piece of equipment on the yacht including the melted spatula, you will have acquired a solid theoretical grounding – as well as an actual one – in generally honing many of the approved and time-honoured techniques of panicking at sea, as recommended by Tom Cunliffe. And if you’re really lucky you may even get a ride in a helicopter.

Apart from being great value for money, these optional modules of the Day Skipper Practical course, provide what’s known as “a lesson well learned,” unless it happens again. And it may well do, as in this all-too-common scenario most RYA instructors, being in my personal experience of them rather humourless, rigid of mind and over precious about a bit of wear

and tear to their boat, are unlikely to award you a pass. Of course, you could try appealing to their better nature, but they haven’t got one, as I found when I said breezily: “Come on, skip, the first thing you said was ‘if you don’t use it, you lose it,’ and I think you’ll agree I’ve used everything on board.”

“Yeah, and I’ve lost the lot,” he retorted rather churlishly. Talk about glass half empty. Negative, or what!

Perhaps I’d been overly familiar calling him “skip,” so I said: “Come on, mate, I’ll buy you a new spatula. How about a pass?”

“What you refer to as a spatula is in fact a chart plotter,” he fumed. “And that one survived the southern ocean before you got your mitts on it.”

“Alright, admiral, keep you powdered wig on,” I reasoned. “What’s a chart plotter?”

As I don’t want to present the profession in a poor light we’ll gloss over the next bit where he really let himself down. I just hope he learned something from that and reflects upon his hysterical outburst. I know I certainly learned a lot.

Speaking of which, they say “every day’s a school day,” but that wasn’t strictly true in my case. In fact, my best ever school report, which I really should get around to framing one day, said: “Not quite sure which one he is.”

My second best one said: “Sets himself a very low standard which he’s incapable of achieving.” When my father read that he beamed with paternal pride and said: “Well done, son, at least it shows you’ve got standards.”

In short, passing my RYA Day Skipper exam was one of the proudest moments of my life – both the boat and skipper even survived. The night-class teachers and practical instructors were among the best educators I’ve come across. I reckon there’s a life time of learning in that course alone, if only I could remember any of it, so I’m thinking of enrolling for Day Skipper Practical again, but all the local sailing schools seemed to be booked solid. Funny that! I even tried contacting the instructor who awarded me my pass, but he’s now running a pangolin sanctuary in a landlocked country in South America.

Every day’s a school day