>> Torque sensor tech >> Vehicle control units >> Hypercar newcomers

Of all the newcomers, Alpine looks most likely to cause an upset

French outfit, Alpine, has long been around the endurance racing scene with its partner team, Signatech. The collaboration won the WEC LMP2 title twice and then stepped up to Hypercar with a grandfathered ex-Rebellion ORECA LMP1, running it for two years.

There was never any doubt that the Renault brand would follow its compatriot, Peugeot, into the LMH / LMDh era but, in doing so, it took several low-cost short cuts. The first was to use the ORECA chassis that was already developed by the prolific French constructor, and campaigned by Acura in the US. The Alpine A424 was pretty much sorted from that perspective; it just needed an engine.

For that, Alpine Racing vice president, Bruno Famin, rekindled his relationship with Mecachrome, which delivered the diesel engines for the Peugeot 908 programme when he was technical director there. Mecachrome had an existing F2 engine capable of producing the power required by the Hypercar regulations, with only relatively small adaptations. ‘With Mecachrome, we made quite a lot of changes from an F2 engine to a 24-hours engine,’ says Yann Paranthoën, Alpine Endurance Team technical manager. ‘All the camshafts are different to optimise the construction of the car and the connecting rods are different from an F2 engine. We also focused a lot on the electronics, sensors and looms to optimise all the parts and their reliability for the 24 Hours [of Le Mans].

‘I will not tell you all the materials used on this engine, but it was quite a long way to do it, and it’s still not finished.’

Tyre warm-up is a particular area of concern for Alpine. Tyre warmers were banned from the WEC, with the exception of last year’s Le Mans, but teams are finding other ways round the issue. Porsche, in particular, has developed a quick heating method that allows its cars to gain lap time quickly, either early in a stint or in qualifying.

‘If you lose five to 15 seconds during the first two laps on cold tyres, it is too much compared to being two tenths faster during the 20-25 other laps,’ says Paranthoën.

Of course, tyre warm-up is also affected by driving style, as well as front and rear stiffness, both of which are being honed by the team from track to track.

From an electronics standpoint, Alpine can lean on its Formula 1 colleagues to manage battery regen’ and deployment strategies. However, the endurance squad has remained faithful to the Bosch ECU, while the F1 team uses the McLaren TAG system, so there is not direct technology transfer between the two programmes.

Like Lamborghini, Alpine must also work on ride control, ensuring it can use the kerbs and manage bumps while staying within the maximum power curve. It made a big step in the right direction between Imola and Spa and hopes to make similar gains heading into Le Mans where it will be competing on home soil.

In terms of reliability, Alpine has finished every race it has started, and pace is steadily improving. Of all the newcomers, then, this one looks the most likely to cause an upset.

‘If you lose five to 15 seconds during the first two laps on cold tyres, it is too much compared to being two tenths faster during the 20-25 other laps’

Yann Paranthoën, technical manager at Alpine Endurance Team

BMW is back in the WEC after a one-season GTE-Pro stint in 2018-19, but is hoping for greater things with its LMDh challenger. The Dallara chassis is powered by a derivative of the German manufacturer’s old 4.0-litre, V8, DTM engine, and it has been developed in race conditions by RLL in IMSA ahead of WRT’s two-car attack on the WEC this year. However, much of its WEC pre-season testing was conducted in the wet, so the team has very little meaningful data.

By way of compensation, the WRT team tried to take several steps forward, almost too many at one time, and didn’t fully understand the consequences, positive or negative. At Imola, therefore, it stepped back a little to work through car set-up methodically.

Like its rivals, the BMW is also struggling to deliver peak power, notably over bumps, which has led to a drop in performance compared to that proposed by the BoP.

Using a modified version of one of its old DTM engines, a Dallara chassis and the experienced WRT team, BMW should be further ahead than it is, but has been off the pace in the rounds held so far

After years of struggling and complaining, the WEC is implementing a new BoP system this year, but with some key details hidden

By Andrew CottonAt last year’s 24 Hours of Le Mans, Toyota bore the brunt of a last-minute change to the BoP, so the ACO and FIA are hopeful the new system they have come up with will level the playing field fairly ahead of this year’s race

The ongoing saga of Balance of Performance (BoP) took some dramatic steps in the early part of 2024. The FIA and ACO presented their new method of balancing the Hypercars to the media at the opening round of the FIA World Endurance Championship in Qatar.

Shortly afterwards, IMSA announced that the method it implemented in GTD at the Daytona 24 Hours was too complicated to replicate for the remainder

of the season and so, in agreement with the manufacturers, reverted to last year’s more traditional system.

The performance balancing system for the WEC’s flourishing top class was controversial last year. Engineers used first order parameters of weight, power and aerodynamic efficiency to balance the cars.

Toyota, however, proved better than anyone else under race conditions, particularly on second order parameters

such as tyre wear and strategy, and won the opening races comfortably.

So, for the centenary race at Le Mans, the FIA and ACO changed their minds. Instead of leaving the BoP alone until after Le Mans to prevent sandbagging, as promised, they took into account the second order parameters and promptly upset Toyota. There were even rumours the Japanese manufacturer would cancel its hydrogen programme in protest.

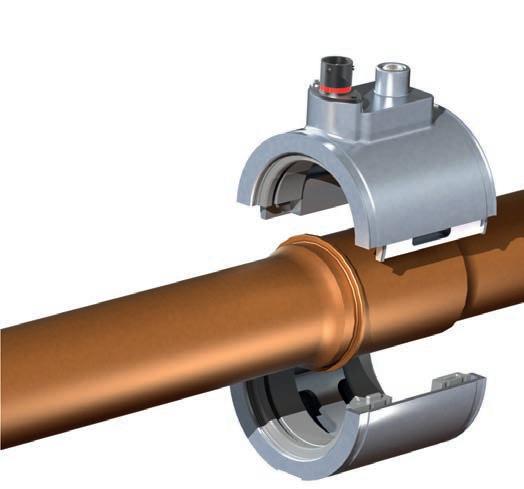

Sensors are clamped over the driveshaft at MagCanica in California, and held in place by a shoulder and an arm connecting the sensor to the chassis

metallurgical properties, typically strength, weight, hardness. Now, we come in and magnetise them in a very specific way.

‘What we do is take a short portion of the [drive]shaft, typically 20-30mm, and we magnetise it circularly.

‘With most materials, you torque them and there is no relation with their magnetisation, nothing happens. But because these materials are magnetoelastic, there is an immediate, pretty linear relationship between how much torque you put on and how much twist you generate.

‘That magnetisation, which was purely circular, then wants to tilt over. It senses the torque [applied] and wants to gravitate toward that 45-degree helix. So, what was previously a purely circular field, completely contained within the steel and externally undetectable, now just a small portion of it will leak out. That causes a relatively weak magnetic field, formed in a sort of doughnut shape around that portion of the shaft. The intensity of that field is proportional to the amount of torque you put on.

‘The beauty of it is that it’s reversible. So when you relax the torque, it goes back to being purely circular. Put the torque back on and it leaks again.’

Having taken a reading from a spinning object within the sensor, the measurement is turned into an electrical signal that is amplified and then converted into an analogue output. The output of the MagCanica system is 4.5kHz, which is considerably higher than rival systems.

‘A lot of the other systems may have the sufficient frequency response, electrically, but often they don’t,’ says Bitar. ‘Even if they do, a lot of the time they can’t physically get embedded in the locations where you have that high frequency content to begin with.

‘As an example, the frequency content of an MGU shaft signal is higher than a mainshaft, which is higher than on a clutch shaft, which is higher than a driveshaft. So part of the trick is, can you even get in to these locations in the first place?

‘The second aspect of it is, are you able to keep up the pace, electrically? The main reason we [MagCanica] are able to do that is the interaction between the shafts, their mechanical properties and magnetic properties. And all this is happening at a velocity that is really only limited by the speed of sound propagation within the metal. It tends to be very, very fast.

‘So, if you think about the shaft itself, it has a super high bandwidth of tens of kilohertz. For your limiting factors in your electronics, can you come up with a method of magnetic field measurement that is sufficiently fast paced to be able to keep up with those variations? We’re basically at five kilohertz. We probably could go higher, but honestly, even five is more than most people seem to need, or want.’

The sensor is held in place by an anti-rotation device (ARD), a fancy word for an anchor attached to the car at one end that stops the sensor from rotating with the driveshaft. The installation of that is up to the teams.

On top of the sensor are two ports, one a mechanical connection to the sensor, the other an electrical sensor that effectively provides power to the unit.

There have been a few sensor failures, notably in the 2023 race at Portimão, where Toyota was forced to change a corner on its leading car and Peugeot also had issues. However, the sensors are now widely believed to be reliable in prototypes, while the FIA has developed measures to keep cars running with a faulty sensor.

For GT cars, however, things are a little more complicated. Manufacturers such as Porsche have introduced a steep angle of driveshaft from the gearbox, which presents challenges not seen in prototype racing.

‘The main thing that makes the driveshaft installations more challenging – maybe not so much operationally, but from the point of view of mechanical design – is the fact that the driveshaft does this moving on you,’ says Bitar.

‘Accommodating the angular motion and the axial plunge of the driveshaft can be a little bit challenging.

‘The other thing a lot of our competitors struggle with is that many racing driveshafts have integral tripod joints, either on one end or on both ends. A lot of torque sensors, including some of ours, would ideally slide over the shafts axially, but that’s not always possible. So you really need something like a clamshell that you can radially mount. We are able to do that with our driveshaft product.’

Information gathered by the sensor is then sent to the sanctioning body’s engineering team, who use it to monitor the car’s performance through torque delivery at the

Torque sensors can be fitted to any spinning shaft to which torque is applied, though the frequency content differs depending on application. Accessibility is also an issue, hence why in motorsport they are most commonly fitted to driveshafts

‘When you’re trying to balance performance among the competitors, the torque is around 1000Nm on a driveshaft, but when you hit a kerb, or dump the clutch at launch, you can easily see 5000Nm’

Sami Bitar

wheels. That makes it sound easier than it is. For while the power curve for the engine is defined, and teams work hard to get as close to that curve as they can, any time there is a spike above the line, the sanctioning body takes a look. If it happens regularly, a penalty is applied for exceeding the parameters, even if it is not necessarily intentional. Kerb strikes are a common cause of a spike, and even just bumps in a track.

The system is so sensitive that even driving style can make a difference. A driver with a smooth, flowing style will need less help from the electronics to stay close to the torque curve, and will likely be faster, too.

‘I’m not going to give you precise numbers but, when you’re trying to balance performance among the competitors, the

torque is around 1000Nm on a driveshaft,’ says Bitar, ‘but when you hit a kerb, or dump the clutch at launch, you can easily see 5000Nm. So, when you hear a sensor company tell you they measure to within one per cent of full scale, one per cent of 5000 is 50Nm. 50 out of 1000 is five per cent, and you’re not going to be able to do BoP that way. So the quarter per cent is a quarter per cent of reading so, roughly speaking, you need to be within 2.5Nm.

‘Our product has been specifically developed for the utmost accuracy.’

As the sanctioning bodies roll out this technology, they are always looking for cheaper options. Right now, though, MagCanica is the only company delivering the required level of accuracy in races.