that

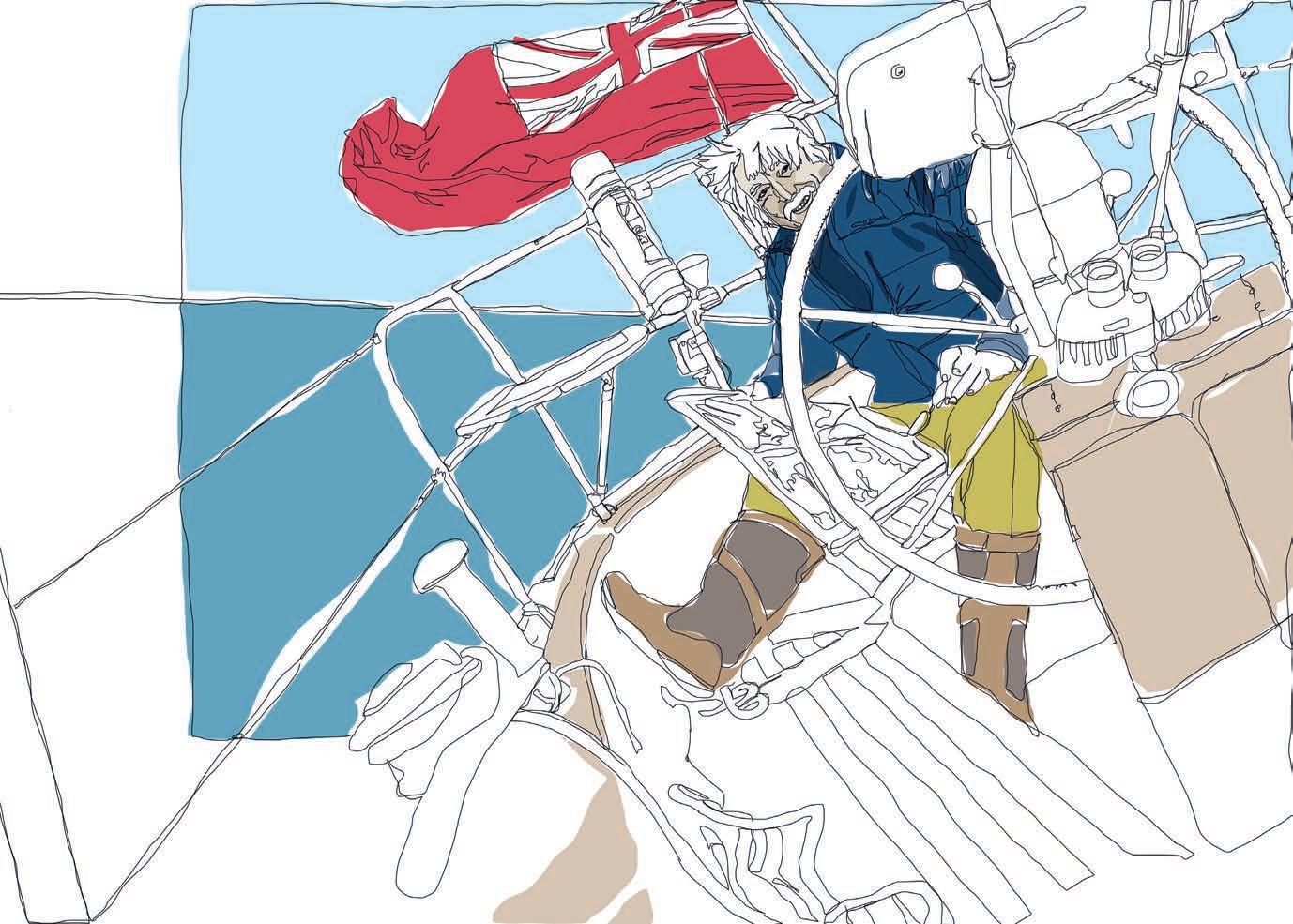

Dealing with unwanted guests, particularly when moored up on the dockside, takes skill and perseverance

Truly, the sea is full of surprises. For the tropical sailor these may come as flying fish peppering the watch on deck on a dark night. My wife Roz was once enjoying a few minutes snooze while tending the helm in mid-Atlantic when a substantial specimen smacked into her at chest height. This brought her naughty slumbers up with a round turn. Robbing her shipmates of a

rather bony breakfast she shovelled it over the side, got back on course and fell to pondering why, with all the wide ocean to fly above, this one chose to bump into her. Fish seem to be attracted by light. The night was moonless with the constellation of Scorpio putting on a brave show. Jupiter, high in the sky in those latitudes, was blazing like a beacon. How come, she asked herself, had the aerobatics expert picked on her? Our private ocean sailing took place

PODCAST

Catch up with Tom’s columns now and in the future at sailingtoday.co.uk

in traditional craft with no electronic instrumentation, so she wasn’t being dazzled by brightly lit numbers. Far away from any shipping lanes with a watch permanently on deck and mostly wide awake, we saved our batteries by keeping the navigation lights off and running dark. This was general practice in voyaging yachts in those days before windmills, solar panels and the rest, when the only unlit object you were in with any chance of hitting would

“In the morning, only the fish scales on her jumper bore witness to her night’s career”

be another yacht. The few sailing the tradewind belts were all going the same way so the likelihood of collision was vanishingly small. The sole bulb we had burning was the compass light so, to avoid any further encounters, she turned it off and steered on a star instead. Problem solved. With her eyes now in total night-vision mode, she was treated to the rare sight of more flying fish taking off in the glimmer of the Milky Way, dripping fire from the phosphorescence. In the morning, only the fish scales on her jumper bore witness to her night’s career. No matter what the latitude in which a boat finds herself, boarders are generally unwelcome. There’s something refreshingly honest about flying fish. They arrive more by error than intent and they don’t try to hide away, so getting rid of them presents no challenge. There’s also nothing inherently unpleasant about them. They come in clean from the ocean with their big, innocent eyes seeming to plead for release.

Dockside chancers are in a different category altogether. In a house ashore, mice are a nuisance and rats a horror show. Onboard a yacht, the idea of either gives me the total creeps. While that other pest of the floating world, the cockroach, confines its operations to the hotter parts of the planet, rodents know no such frontiers. My current location is 55º05 N, 10º14 E. I’m in Denmark where the harbours are clean by most standards, yet last week a mouse contrived to hop over my rail and establish itself in some hidden cranny. Unlike its distant cousins who still set up home in my loft now and again, this one was ghostly quiet. We knew it was there because it had decided to share the artisan loaf we’d bought in the local bakery to treat ourselves. When we roused it out of the bread locker at breakfast, we found a neat aperture nibbled in the wrapper and a small crater the size of an old-fashioned gobstopper amidships in our lovely loaf.

I’ve shipped aboard most things from modern race boats to 100-yearold wooden sailing ships, but I’ve

never before had mice on board. Perhaps I’ve just been lucky, but there was no doubting that we had one or more on board now. It had to go, and go quickly, before it got used to its new home, invited its chums to share its lodgings and started a family. Praying that there was only one, I ate my bread-free breakfast then ran down to the local chandler in search of a mousetrap. This was a promising establishment with a lot more on its wooden shelves than a load of plastic bags with the wrong size of screw and racks of pricey waterproofs, but the lady proprietor said that in 30 years tending to the needs of passing mariners she had never before been asked for a mousetrap. Stocking them, she said, would have involved capital lying dormant for decades, a luxury she couldn’t afford, so she sent me on a route march to an out-of-town hardware megastore where I scored a pack of three for the equivalent of £1.50. The deal seemed almost too good to be true and, as is often the case, so it turned out to be. The Scot on the next boat, an expert in rodent control from years in the east coast

The INEOS America’s Cup team has built on its relationship with Mercedes Formula 1 engineers to develop its Britannia AC75. By Andrew Cotton

The America’s Cup has long been associated with advanced technology. For the 2021 edition in New Zealand, Britain’s INEOS crew joined forces with the Mercedes Formula 1 team of engineers to help in its quest to win the coveted title.

The relationship was developed late in the competition, when the team was struggling to achieve the desired results. That meant the engineers had only limited time to step in, but the outcome was undeniable. The team recovered form and, although it didn’t win the competition, it certainly felt the benefit of the relationship.

That, then, was the cue to continue into the 2024 edition together. Starting earlier this

time, and more carefully allocating resources from the beginning, the development path of the team, the boat and the project was extreme.

The design team of the 2024 boat moved close to the Brackley F1 headquarters, to an airfield with a hanger large enough to house the build of the vessel. That allowed the Britannia yacht designers to integrate fully with the F1 designers and engineers, making full use of the latter’s available facilities.

One of the decisions taken early, and as a result of this move, was to build a test boat, rather than adapt the previous competition boat, or work on an existing AC 40 yacht (a smaller version of the AC 75 that would be used in competition).

Using the F1 team’s expertise in producing prototypes to a tight schedule, and now to a cost cap, played a key part in making that decision.

“The famous saying in sport is that you can be over budget, or behind on your timeline; hitting both is pretty hard,” says Sir Ben Ainslie, the skipper of the crew, team principal and CEO of the INEOS America’s Cup project. “In sport, you have to make the timeline, because they are not going to postpone the start of the race for us.

“We had a big decision to make early on in the campaign, whether or not to build our own test boat. We could have had the same as the other teams, which is one design

[the AC 40] and bolt on your open foils and control systems. That’s a much easier way of doing it.

“However, we made the decision that we wanted to design and build our own test boat, given the partnership with Mercedes, because a lot of the designers there had never done that. It was well worth the process to go through because it highlighted a number of areas we needed to improve on for the eventual race boat.”

The test boat turned out to be more important than first realised. By the team’s own admission there was a lot of over engineering in it, so the second version, that which competed in the 2024 competition, was revised and much more effective.

“Last time around [in the 36th edition of the Cup], we were supporting certain specific things, whether it was along the areas of controls, some specific engineering design and testing and some other software-related tools,” says Geoff Willis, a former technical director in F1 who now holds the same position on the America’s Cup team. “This time, it’s been very much integrated.”

Many of the F1 engineers that helped with the design and build of the Britannia AC 75 have now returned to their regular jobs on the grand prix team. Before they did, though, they worked on all parts of the boat, alongside the experienced yachting design team, assisting in CFD, cell design simulation, software, materials, composite design and powertrain.

“Clearly, there are experiences and skill sets that are different between the two groups, but I think it’s worth rewinding a little bit and emphasising just how impressively overlapped

the F1 world and the yacht world is,” says Willis. “Consider that we’ve got carbonfibre composite structures, mechanical systems, transmission systems and hydraulic systems, with electro-hydraulic control pumps. We also have lots of aerodynamics and hydrodynamics; let’s just call it fluid dynamics. It’s pretty much the same.

“Mathematically, there are a couple of features that would be new to the F1 world, specifically hydrofoils with cavitation and ventilation. But for all the fluid analysis, all the aerodynamicists in the F1 world would have been well aware of that in their background, training and experience. So, you’ve got all these areas of technical expertise, which are amazingly well aligned.”

Grand prix teams generally have a stable core that develop cars together and compete multiple times per year. To do this, they have teams of designers and engineers in the team HQ, but in the America’s Cup there is a small group that generally competes every couple of years, in regattas building up to the main competition, and then the competition itself.

ABOVE RIGHT

The overlap between F1 and the America's Cup yachts proved to be considerable –one example being the hydraulics

ABOVE LEFT

Stowing the headsail on INEOS Britannia post sea trials

BELOW

Ben Ainslie, the driving force behind the INEOS Britannia challenge

“A difference in culture is that the Formula 1 teams, for the main part, have had lots of continuity and stability,” confirms Willis. “Decades of it, and this has allowed the teams to build up an enormous base of teamcentred IP capability and technology. People do move between teams, but the team doesn’t lose the stability.

“With the possible exception of team New Zealand, [the America’s Cup teams] are much more episodic. Come together, work together, work out how to do it. And then a certain amount of that is dissolved at the end of the Cup cycle. Then the next one moves on.”

Using the stable core, the INEOS team started work early on its 2024 contender. The rules allow for one test boat and one competition vessel to be built, and that’s the route they chose to take.

“The protocol allowed us to build three foils with the wings and flaps, with fundamentally the same design,” says Willis. “You can have evolutions of them, but you can’t have completely different concepts of 80 per cent of your foils. The 80 per cent of the foil that goes on the boat must be from common stock, what’s called the immutable part. That put us in the situation of asking what are we going to do with the time we’ve got until we have to commit to design before manufacturer until we go testing on the water?”

Willis continued: “There’s clearly a lot of opportunity, so we wanted to make sure we best used that. We could either sail the old yacht, or there was the proposal for the AC40s – this small class of single design foiling yacht, built by Team New Zealand – or

The Cape Verde Islands are perfectly placed for a transatlantic stop off enroute to the Caribbean – yet they are often overlooked. Michelle Shultz explains their allure

The Cape Verdes remain an off-the-beatenpath archipelago to sail around. At any given time you may feel as though you could be in Portugal sipping sherry, mainland Africa with kids around in a circle listening to stories, or feel like you’re walking on Mars. That would be the Cape Verde Islands off the West coast of Africa. Is it safe? Ask the voyagers from Europe that holiday there each year. Yes.

Let’s dive into why Cape Verde should be added to your passage plan. If you are in Europe and plan to sail to the Caribbean or South America, you wouldn’t even have to change your passage plan by much. Cape Verde is right along the speedy path for sailing into Grenada or South America and you get to take in another archipelago. For us speed is important as we have bought a production yacht and think we will break sound barriers somehow to get to our destinations. We must have skipped the specs part of how fast we would sail on average. I know, you added length to the hull, bought racing sails, and added a bowsprit for more canvas. Now we are half a knot faster and we won’t mention the amount of money to get that half a knot. Anyhow, back to why you won’t want to miss Cape Verde. It is an adventurer’s wonderland with a dash of cultural delight and a diverse landscape – from flat beaches to volcanoes. There is even some history of the islands being used for the transatlantic slave trade and refuge for victims of religious persecution. Then once you have paid homage, it’s time to climb volcanoes, walk in soft sand, and get to know the locals who live in a caldera with hardened lava.

Let’s talk about planning before we dive into the details that will have you hoisting your sail and pointing the bow towards Cape Verde. January to March there is the probability of Force 5-7 winds so that isn’t fun. Harmattan (sands from the Sahara) is from the end of November to midMarch so you will likely see some dust, but I’m not sure you can avoid this in the southern Atlantic at all. Then there is the dreaded hurricane season in the Atlantic to avoid unless you like the stress of trying to

Dreaming of dropping everything to sail the world? Sailing La Vagabonde Riley Whitelum and Elayna Carausu have done just that, becoming parents, digital yacht nomads and internet sensations in the process. Milly Karsten catches up for a chat