15 minute read

Labeline puts Roadshow on the web

SCREEN TIME

REPORT • LABELINE MOVED ITS BIENNIAL ROADSHOW ONLINE BUT THE REVAMPED ‘WEBSHOW’ PROVED VERY POPULAR AND MANAGED TO DELIVER A LOT OF CRUCIAL INFORMATION

THIS COMING 1 January marks the arrival of the biennial updates to the various modal and regional regulations governing the transport of dangerous goods – although there are a variety of transitional periods and delays to complicate multimodal operations. By rights, that deadline, which rolls around with depressing regularity every two years, should have been marked by gatherings of dangerous goods professionals, eager to make sure they were keeping up to date. But, in this strangest of years, travel restrictions and social distancing measures meant that those events had to move themselves into the virtual world.

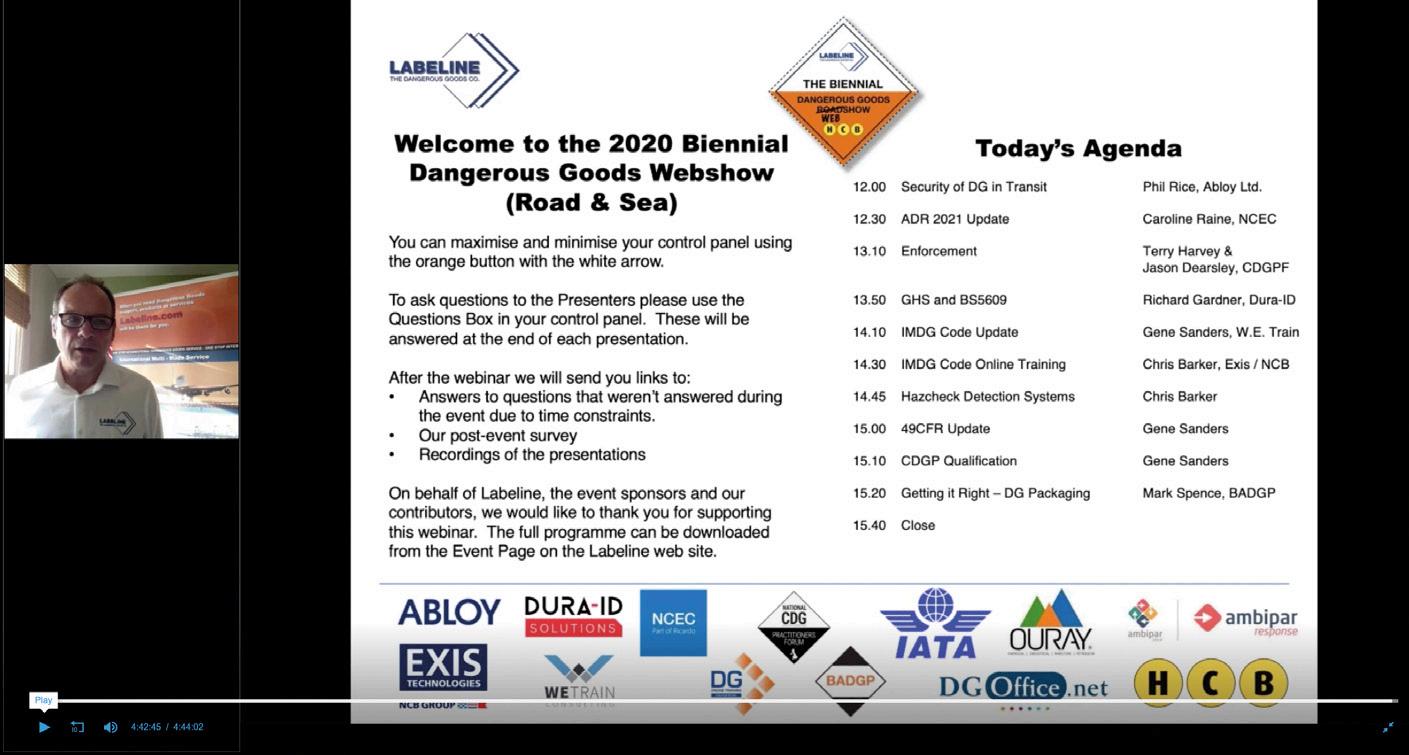

In the UK, one of the most useful of those events is Labeline’s Biennial Roadshow, which has been strongly supported by HCB over the past few years. While there had been plans in place to hold the one-day event in two venues, overwhelming forces led to it being moved online and it took place over three successive Tuesdays during September.

Labeline has pursued a policy of making the event as cheap to attend as possible, so as to spread the word around as many people as it can – the dangerous goods function regularly being rewarded with a desultory budget in many companies. So moving it online meant that it was even cheaper than normal: attendees did not have to travel, did not have to get their suit cleaned, and did not have to pay the modest charge to register. Indeed, the presentations were recorded and are available for anyone to view, free of charge, on the Labeline website at www.labeline.com/ dangerous-goods-webshow/.

Given that free-to-view package, the hastily renamed Labeline Biennial Dangerous Goods Webshow attracted nearly 900 registrants, well in excess of attendance at recent physical events. It also attracted a wider range of sponsors, some of whom took the opportunity to speak and explain their goods and services to the audience.

GETTING AROUND The Webshow was split into three days, each running for a few hours in the afternoon (UK time), so as not to force viewers into peering into their screen for too long. Even so, it was notable to hear pleas for a coffee break every so often, which is perhaps a learning that can be taken away by others planning a similar virtual event.

The first day concentrated on the transport of dangerous goods by road and sea. The new edition of ADR, the regulations governing the transport of dangerous goods by road not just in Europe but increasingly in other parts of the world, is now available. Caroline Raine from the National Chemical Emergency Centre (NCEC) took attendees through the

LABELINE HAS PLENTY OF COPIES OF ADR 2021

major changes. She stressed, however, that her presentation was based on the draft amendments to Annexes A and B of ADR, with the revised edition still awaiting formal adoption at the beginning of October.

The 2021 edition of ADR will contain fewer changes than is usual and fewer than it might have done had WP15, the body responsible for its maintenance, been able to hold its planned session in May, where there were some outstanding issues to be discussed. These will now have to roll over to the 2023 edition, unless contracting states decide to bring them forward through the use of multilateral special agreements.

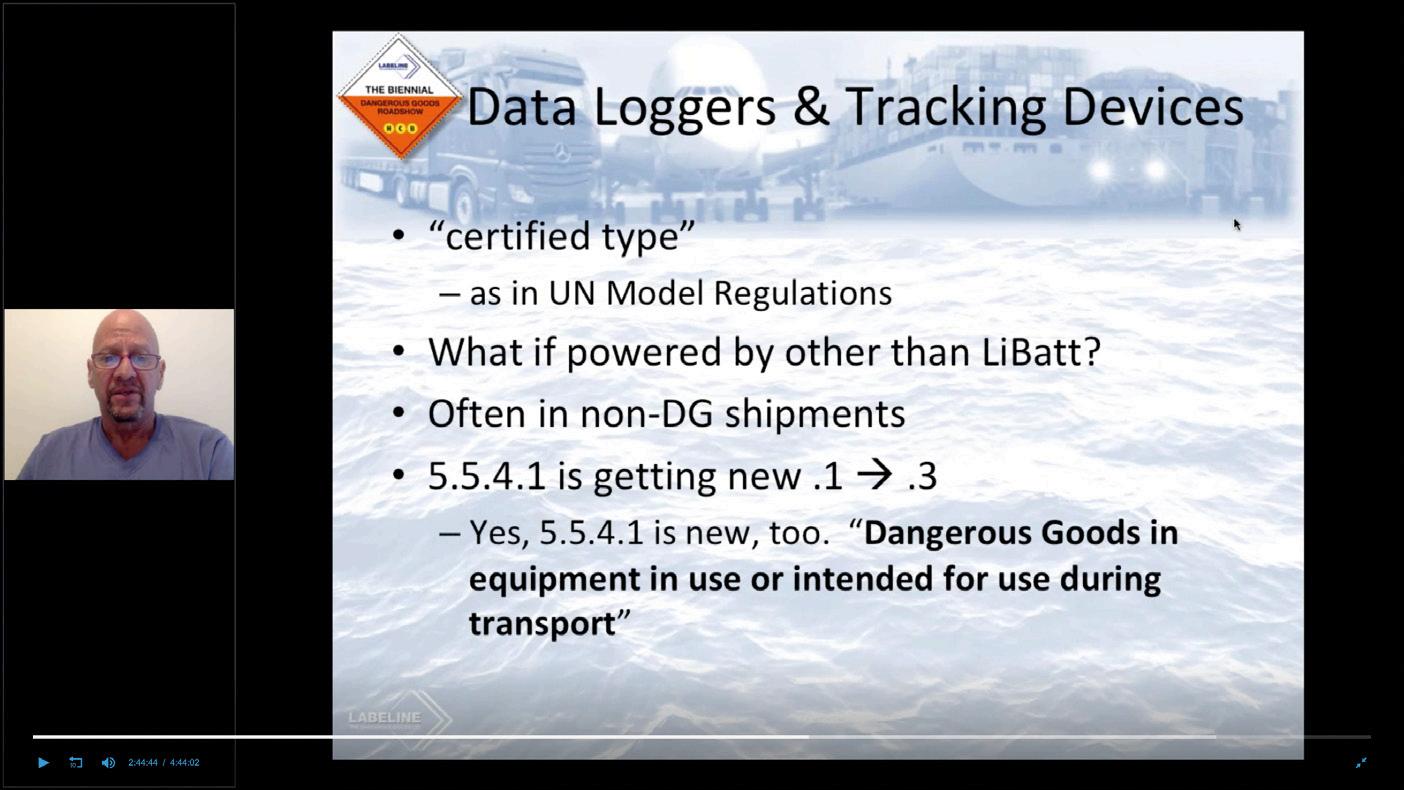

NEW IN ADR Looking at the detail of ADR 2021, Raine said that there are only four new UN entries; three cover electronic detonators (UN 0511, 0512 and 0513), while UN 3549 addresses solid medical waste of Category A. This was prompted by the difficulty in dealing with large volumes of waste material during the response to the Ebola virus outbreaks but it may well come in handy in the future. UN 3549 is not covered by the exemption in 1.1.3.6, Raine noted. On the other hand, the exemption in 1.1.3.7(b) has been revised to clarify that it applies to data loggers.

Data loggers also came up in the new 5.5.4, relating to dangerous goods in equipment in use or intended for use during transport. Theoretically at least, this also applies to those shipping or carrying non-dangerous goods, as do other parts of Chapter 5.5.

Much of the detail of Raine’s presentation was covered in HCB’s report on the ADR revisions (see October 2020, page 104). It is worth, though, highlighting the new special provision 390 dealing with the transport of lithium batteries packed with and in equipment in combined packaging, the update to tank provision TP19 on minimum shell thicknesses, the various changes to the marking and labelling specifications in Chapter 5, and the new 6.1.3.14 on packagings that have been tested to more than one design type. This last item reflects common industry practice, Raine noted.

Raine also mentioned that various competent authorities had put in place relief from certain provisions in light of Covidrelated restrictions; these covered, inter alia, the expiry of tank and packaging certifications, drivers’ hours of service, and recurrent training. Many of these temporary measures are approaching their end date and it is not year clear if or when they will be renewed; dutyholders should be alert to any changes and disruption that they could cause.

Raine concluded by reporting that the new transitional legislation for the GB Carriage of Dangerous Goods etc Regulations, to reflect the UK’s eventual full exit from the EU, was expected to be published shortly. [The legislation was subsequently made on 12 October.] While much of this amending regulation deals with the technicalities of the UK no longer being an EU member state, there is one substantive change: the replacement of the current EU ‘pi’ mark for pressure receptacles with a new and corresponding ‘rho’ mark for those pressure receptacles manufactured in the UK.

CODE BREAKERS If a virtual event means that attendees do not have to travel, the same is true for the presenters. And, while Gene Sanders was due to have given an in-person training session on the Certified Dangerous Goods Practitioner qualification, he was still able to give his presentation on the upcoming changes to the International Maritime Dangerous Goods (IMDG) Code from his home base in Florida.

Sanders, an independent trainer and consultant, and also an HCB columnist, stressed that he could only speak about the expected changes, since the final text of Amendment 40-20 to the Code had not yet been finalised (and is still not). It is due to enter into force on a voluntary basis on 1 January 2021 and will become mandatory on 1 January 2022. As with ADR, the extent of the changes in the IMDG Code is not as »

broad as might normally be expected and many of the amendments are the same as those in ADR, drawn as they are from the 21st revised edition of the UN Model Regulations, which was adopted in December 2018.

Sanders also stressed that ‘Editorial Corrections’ to the current IMDG Code, Amendment 39-18, will not be flagged up as changes in Amendment 40-20, so users will need to be alert to that and make sure that they have those corrections in hand.

Part of Sanders’ presentation dealt with changes that have not happened. For instance, there were proposals for amendment and editorial corrections put forward relating to the provisions for fumigated cargo transport units but no amendments were made. Similarly, there have been discussions over special provision 76, which allows competent authorities to provide approval for the transport of goods that are otherwise forbidden. However, some states give no such approvals, others give approvals for some products; this leads to modal disharmony, especially if the same goods are forbidden for carriage by other modes. Sanders said that some guidance on the topic is likely and there may be a revision in due course to move the provisions into an SP9xx mode-specific special provision.

Specific to the IMDG Code, there are a number of changes to the segregation provisions. Sanders noted in particular a rewording of SG53 to require certain products to be kept away from non-dangerous liquid organic materials, which tend to be combustible, although no guidance is given and it may prove difficult to comply.

MORE FROM BIG DADDY Elsewhere in the new IMDG Code, 2,4 dichlorophenol, which has no specific proper shipping name, is being moved from UN 2020 Chlorophenols, solid to UN 2923 Corrosive solid, toxic, nos, as, on the basis of test data, it has a corrosive hazard. It will now be Class 8 (6.1, P) rather than Division 6.1 (P).

The filling and discharge of portable tanks aboard ship is not allowed, though the provision will be clarified to allow the use of salvage packaging in the event of a leak.

The dangerous goods declaration will have to show when the Limited or Excepted Quantity provisions are used, the change appearing in 5.4.3.2.1. This is consistent with the provisions in Chapters 3.4 and 3.5. The requirement to show the flash point on the DG declaration does not apply to Division 4.1 materials, though some sublimate (moving directly from solid to vapour) and perhaps it should apply. The provision will be clarified to state that the flash point shall only be shown on declarations for substances that have a Class 3 primary or subsidiary hazard with a flash point below or equal to 60˚C.

The IMDG Code will now contain a provision in 6.8.3.1.2.1.2 to allow the use of fibrereinforced plastics (FRP) portable tanks with competent authority approval, in which case they will be treated as IMO 4 tanks. However, Sanders pointed out, the UN Sub-committee of Experts is also looking at FRP tanks so there may be further changes to come.

There may also be some action on the classification of carbon and charcoal (UN 1361 and 1362) in order to have modal harmonisation on the circumstances under which these products can be shipped unregulated. Discussion so far has centred on the entry in column (17) of the Dangerous Goods List, which may change, Sanders said. HCB readers should be aware that there have been a number of serious fires

EXPERT SPEAKERS FROM AROUND THE WORLD

aboard containerships that have been traced to charcoal shipments, so IMO will need to get this right.

While he was on the call, Labeline had asked Sanders to provide an update on the US Hazardous Materials Regulations in 49 CFR, though as he pointed out, there had not been much activity recently. The final rule under HM-215O was published on 11 May this year; this is the international harmonisation rule, which brought the US into line with the modal provisions that took effect at the start of 2019, so the US regulators are getting a little behind. A notice of proposed rulemaking under HM-215P, the next biennial harmonisation rule, was due by August 2020 but has so far not appeared.

One item in HM-215O was a renewed definition of polymerising substances; shippers should be aware that the US definition does not exactly align with the UN’s cut-offs for self-accelerating decomposition temperature and is, in fact, more restrictive.

THE FLY GUYS Labeline’s longstanding relationships with the regulatory bodies means that it can reach out and attract the very highest calibre of speaker to its events. That was certainly the case when it came to an update on the air mode, where presentations were given by Dave Brennan, assistant director, cargo safety and standards at the International Air Transport Association (IATA), whose department is responsible for maintaining the IATA Dangerous Goods Regulations, and Geoff Leach of The Dangerous Goods Office, who for many years was chair of the International Civil Aviation Organisation’s (ICAO) Dangerous Goods Panel.

Brennan ran through some of the major changes that appear in the 62nd edition of the IATA DGR, which takes effect promptly on 1 January 2021 (see HCB October 2020, page 108 for full details). He highlighted a number of issues that those involved in the transport of dangerous goods by air need to be aware of, not least the major new provisions for competency-based training and assessment (CBTA), though these have a two-year transitional period. Employers will now be accountable for ensuring that their staff are competent through assessment and will have to ensure that the training they are given is appropriate to their roles: the tables in 1.5.A/B will be deleted, with the aim of making employers give more thought to the specific training required for each individual.

Elsewhere, there are some changes in line with other modal regulations and various amendments to the special provisions. Brennan thought that the revised A215, dealing with the technical name for environmentally hazardous substances, may be challenging and stressed that the technical name must appear elsewhere in the Dangerous Goods List in capitals.

IATA has also toughened up the packing instruction relating to solids containing dangerous goods. This follows an incident in which packages containing hand wipes leaked in transit.

IATA draws its DGR mainly on the basis of ICAO’s Technical Instructions; Brennan noted that ICAO has varied from other modes in the application of the new provisions for data loggers, fearing that large batteries might end up in air transport without regulation. Discussions on this topic are ongoing and Brennan felt that an addendum might appear (Leach thought it unlikely) in order to facilitate multimodal shipments.

MOVE ONLINE Following a presentation by Scott Dimmock of Dangerous Goods Online Training, Leach discussed issues surrounding the delivery of training online, especially when the new CBTA provisions are arriving. “Necessity is the mother of invention,” he observed, saying that the Covid-19 pandemic has made in-person training virtually impossible. It was necessary to find ways of transferring classroom training to a webinar format.

What Leach has found is that there are some unexpected practical challenges. For a start, the IATA DGR is copyright material, unlike ADR. It cannot be copied, so students have to be provided with an actual copy of the regulations, along with workbooks. So much is fairly straightforward – it is getting the valuable IATA regulations back that is a problem.»

In addition, Leach said, companies need to make sure their employees have the time to take the course and concentrate on it – they cannot be distracted by other tasks. “Is this the new normal?” Leach asked. “I sincerely hope not!” It is vital for those active in the dangerous goods supply chain, not just trainers, to get out and meet people. But online training will, he hoped, provide a model for reaching remote locations in future.

Herman Teering of DGOffice looked at digitisation more broadly, noting that IATA began its e-freight project in the mid-2000s. An XML specification for dangerous goods documentation appeared in 2009 but it was only in 2018 that airlines began taking it seriously. DGOffice is helping develop that trend, working in Europe through the Dangerous Goods Transport Information Network Association (DGTINA) and participating in a ‘sandbox’ project in the US and Canada, which is due to run to 2022, although this is more focused on rail transport. IATA has also established a specific work group in the area of XML standards.

The problem comes, Teering said, when various different standards are developed; some of them are mode-specific, which is a shame, he said, though it seems a big task to get a standardised set of data for all types of transport. However, the net is spreading wider all the time, with the EU looking at moving other transport documentation into an electronic sphere.

OFF THE BOOKS There were many other presentations over the three days, covering security, enforcement, response and more. Phil Rice from Abloy Ltd, one of the sponsors, introduced attendees to

Abloy’s new high-security locking system, which leverages the benefits of digitisation to not only provide its clients with the assurance that their shipments are not being stolen or tampered with, but also to restrict access to those who need it.

For instance, Rice said, a ‘smart’ lock such as Abloy’s new CLIQ Connect Key can tell the owner who opened the container and where, when and for how long it was open. It can be set to only allow access at a certain place and does not even need a key – a code can be sent to a mobile phone that will open the lock.

Attendees also heard from Terry Harvey and Jason Dearsley, respectively chair and vice-chair of the CDG Practitioners Forum, established in 2000 to allow police forces in the UK to share best enforcement practice and their experiences of dangerous goods on the road. They showed some examples of bad practice which, sadly, seem all too common and all too difficult to eradicate.

Mark Spence, chair of the British Association of DG Professionals (BADGP), illustrated the rights and wrongs of dangerous goods packaging, citing plenty of examples that he has come across in his many years as a Dangerous Goods Safety Adviser.

Jon Lang from NCEC gave an insight into the expectations and requirements for delivering specialist advice over the phone to those dealing with chemical incidents. Nick Bailey from Ambipar Response and Aaron Montgomery, CEO of Ouray Group, gave an overview of the specialist resources needed to carry out clean-up, post incident clean-up and remediation, known as level 3 response, in various parts of the world.

At the end of the event, Keith Kingham, Labeline’s managing director, expressed his pleasure at the level of engagement. “I am delighted that so many of our customers from around the world were able to attend the Webshow - and that we had such a positive feedback from both attendees and sponsors. Labeline is much more than a one-stop shop for DG compliance, we are pleased to support the sector by sponsoring the industry’s trade associations and investing in events such as this.”

Since the event, Labeline has taken delivery of its stock of ADR 2021 and is also supplying RID 2021 and the IATA DGR. www.labeline.com