10 minute read

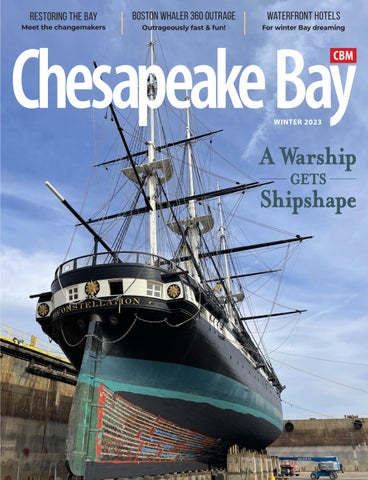

USS Constellation Gets a WELCOME REFIT

The Bay’s oldest and largest wooden boat gets the love she needs.

BY JEFFERSON HOLLAND

Driving over the Francis Scott Key Bridge across the Patapsco River, I could see the green knoll of Fort McHenry over my left shoulder with the skyscraper skyline of downtown Baltimore beyond. Over my right shoulder, I was surprised to be able to spot what I was looking for amid the industrial wasteland of Sparrow’s Point: the upright white masts and squared yards silhouetted against the angular arms of gigantic yellow rail cranes. If I could find my way across a maze of highway construction, railroad tracks, gatekeepers and abandoned warehouses, I would make it to the drydock where the USS Constellation was getting her bottom re-caulked.

You can view the Bay Bulletin video by scanning this QR code: the drydock, while the black-and-white hull remained hidden. Perched on the rim, I looked down on the 168-year-old ship, her keel propped up on enormous blocks 30 some feet below. She is nearly 200 feet long from the rudder to the tip of the bowsprit, but sitting there in the corner of the vast reminded me of a toy boat left behind in an empty bathtub.

I got there at noon on one bright, chilly day in early December. As I stood at the tippy-top of the set of metal stairs that cascaded down to the bottom, I saw three tiny figures coming out from under the hull. If the professional caulkers—all internationally renowned for their work on tall ships and traditional vessels of all descriptions—who were hired to do the work the Constellation needed. They were heading off to pursue another ancient tradition for tradesmen of their ilk: lunch.

I climbed down the stairs and found Chris Rowsom on top of a scissor lift, using a trowel to patch a crack in the stem of the ship with a gray, gritty substance that looked just like Portland cement. Imagine my surprise when he informed me that it was Portland cement. “We’re taking care the ship’s watertight integrity,” he explained when he had lowered himself down to my level. Chris is the Executive Director of Historic Ships in Baltimore and Vice President of Living Classrooms Foundation, and the USS Constellation is his charge.

He explained that the ship had been taking on water for the past couple of years—sometimes up to 3,000 gallons per hour. (That’s the volume of nearly 200 kegs of beer. Every hour.) “A wooden ship like this, you should probably drydock every five years or so if nothing else just to make sure that everything is okay,” Rowsom said. The last time they did it was seven years ago. “In this case, we actually had some issues we needed to take care of, so that’s what we’re doing.”

And this isn’t just any old wooden ship; she’s a “sloop-of-war.” In this case, we’re not talking about a singlemasted boat like most modern recreational sailboats. In 17th and 18th century navies, a sloop-of-war was a designation for a fully-rigged ship— usually with three masts—with a single gun deck below the flush weather deck. The Constellation was built in the Gosport Shipyard in Portsmouth, Va., and launched in 1855. She was the last all-sail-powered ship built by the U.S. Navy. Ships built later all had some form of auxiliary steam power.

The Constellation served on the African Squadron, capturing slave ships and freeing hundreds of enslaved people. Later, she delivered food to Ireland during the famine of 1879. She served as a training vessel for the midshipmen at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis until 1893. After that, her provenance became a bit fuzzy. In the early 1900s, she became confused with the ship of the same name that was built in Fells Point and launched in 1797, one of the six original frigates built by the U.S. Navy.

When she eventually landed in Baltimore Harbor in 1968, she was presumed to be that frigate. It wasn’t until she underwent a major reconstruction in the late 1990s that historians concluded that it wasn’t the same ship at all. They determined that the 1797 ship was dismantled in Gosport just about the same time that caulking. “Paying the seams (smearing half of the nearly 5,500 linear feet of seams between them, inch by inch.

The plank ends meet at “butt joints,” which are particularly prone to leakage. Rowsom explained that there are no fewer than 220 such joints on this hull, and to keep them sealed, each one has been covered with a lead patch.

The team of five professional caulkers led by Mike Vlahovich got support from pre-release inmates from Baltimore City Corrections, five young the seams. These bottom planks between the keel and the waterline are just about all that’s left of the original hull; the rest has been replaced or rebuilt over time. The planks were hewn from the heart of white oak, and some are four inches thick, 18 inches wide and up to 50 feet long. Townsend and the other craftsmen re-caulked about

Black men who are learning a new trade. I met Brandon Blount, a young man whose enthusiasm for the project was evident. He challenged me to a game of trivia and we rattled off facts about the ship at one another. This fellow knows his nautical history. He was particularly interested in Frederick Douglass, another young Black man who worked as a caulker in the shipyards of Fells Point not all that far away. While this is Blount’s first real job experience, it will have been his last before earning his freedom, just as caulking was Douglass’ last job before he escaped slavery.

“I’m liking this experience,” Blount told me. He’s learning all kinds of skills he hopes to put to use when he starts his new life outside the correctional system. Painting the bottom is okay, he says, but he really likes to run the forklift. He asked me to take a picture of him to send to his sister and struck a pose, giving the mammoth rudder a hug.

Chris Rowsom said he’s grateful for their help. “Everybody’s been great, I couldn’t have done this without them. They’ve been a really, really valuable asset, and I think they’ve enjoyed their time here as well. They definitely have a sense of pride that they’re working on a ship with such history, and particularly on a caulking project, because most of our guys are African American, and in the 1850s the Blacks of Baltimore, free and slaves, were primarily engaged in the caulking trade, so that’s something the guys can relate to from a historical perspective.”

The apprentices are working as part of Living Classrooms’ “Project Serve” program. Project SERVE

(Service, Empowerment, Revitalization, Validation, Employment training) addresses the issue of high unemployment and high recidivism among returning citizens in

Baltimore City. SERVE provides onthe-job training for 150 unemployed adults per year in marketable skills.

The cost of the restoration project—between $850,000 and $1 million—was covered by the State of Maryland, Maryland Heritage Areas Authority, the City of Baltimore’s Capital Cultural Support Fund and Tradepoint Atlantic, which donated the use of the drydock and ancillary support services.

Just eight weeks after the start, on December 19, 2022, with all the seams and butt joints sealed and plied with concrete, and with the hull sporting a new coat of copper-colored bottom paint, the drydock filled up with

Patapsco River water and the ship floated with barely a whisper of a leak. A MacAllister tugboat at her side, the USS Constellation made her way back up the river and moored safely at her berth in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor.

“Constellation is the oldest and largest example of Chesapeake Bay wooden boat building left in existence,” Chris Rowsom told my CBM colleague Cheryl Costello in a video interview for Bay Bulletin. “Once it’s gone, it’s gone. Nobody’s going to be recreating this, so it’s important to preserve. I want our visitors to come away with an appreciation for the people who served aboard her.”

USS Constellation's and its Museum Gallery are located at Pier 1 in Baltimore's Inner Harbor. You can go aboard to take a tour, talk to a crewmember, participate in the Parrott rifle drill, or see what's cooking in the galley. The Constellation also hosts educational and overnight programs for all ages. For information on the Constellation's programs, log onto historicships.org/ explore/uss-constellation.

Through his exploratory voyages in the summer of 1608, Smith visited and mapped the fall lines of all of the Chesapeake’s western shore rivers. The extraordinarily accurate map he published in 1612 served rapid colonization of Virginia and Maryland, though the English treatment of Native communities would prove far less than honorable. As the 17th century progressed, English colonists established trading centers at the fall lines on all of those waterways, as well as the less dramatic heads of navigation on the Eastern Shore rivers. A secondary benefit of those locations was the rapid change in elevation “where the water falleth so rudely.” The resulting energy release made the fall lines good locations for water mills, gristmills and sawmills. We know today that those trading centers turned into villages, then towns, and by the booming 19th century, into cities.

Today, Interstate 95 and old U.S. Route 1 run roughly up the Chesapeake’s western shore fall line. It’s no accident. Once highways took over from rivers for transportation of people and goods, planners laid out those roadways simply to connect the old port cities, from Petersburg on the Appomattox, Richmond on the James and Fredericksburg on the Rappahannock to Alexandria and Georgetown on the Potomac, Elkridge and Baltimore on the Patapsco and Havre de Grace on the Susquehanna. Although the pattern is not as clear on the Eastern Shore, there are cities and towns at or near the heads of navigation on the rivers there, for the same commercial reasons. Each is on a highway. Examples include Millington on the Chester (U.S. Route 301), Denton on the Choptank (Route 404), Seaford (Del.) on the Nanticoke (Route 13), Salisbury on the Wicomico (Route 13), and both Pocomoke City (Route

13) and Snow Hill (Route 12) on the Pocomoke. All those river ports hosted commercial traffic into the mid-20th century before the highways took over transportation. Salisbury still receives regular bulk shipments by river of western shore corn and soybeans for Purdue’s chicken feed mill, and most of these municipalities still have sandand-gravel operations moving product on their waters today.

From a geologist’s point of view, a fall line (or fall zone) is a section of river where a surrounding upland (Piedmont) region meets a coastal plain. The Chesapeake watershed’s Piedmont sits on hard crystalline basement rock, while its coastal plain is softer gravel, sand and mud washed down from the Appalachian and Blue Ridge Mountains over hundreds of millennia. Thus the coastal plain has worn away faster, creating abrupt elevation changes of 50 to 100 feet and resulting rapids. Millions of years ago, those mountains rivalled the Himalayas in height, but rainfall, freezing, thawing and much time have worn them down, creating the rich soils of the Shenandoah Valley, the Piedmont and the coastal plain.

In that light, it’s worth noting that on an Earth time scale, a fall zone is not a static feature. It recedes upstream as the river slowly wears down the rocks over which it falls, exposing bedrock shoals. Remember that the underlying rock layers of the Chesapeake’s western uplands are not uniform in composition and hardness, either in north-south or east-west directions. Each river has carved its own channel, characteristic of the rocks under its bed. In a river with high flow, the abrupt drop that causes a waterfall may be miles upstream from the geologic boundary between the Piedmont’s bedrock and the Coastal Plain’s loose sediments, at significantly higher elevation. The waterfall has slowly migrated upstream, towards the west, as the river has eroded the bedrock at the eastern edge of the Piedmont. Geologists tell us the Potomac has etched the upper lip of its Great Falls 14 miles upstream to an elevation around 150 above sea level during the last 2 million years, running over broken rock remnants—including Little Falls—until its bed reaches tide downstream around Theodore Roosevelt Island and the Kennedy Center. Thus, the Potomac’s fall zone has stretched out for that distance.

By contrast, the North Anna and South Anna Rivers (the headwaters of the Pamunkey, and thus of the York), with smaller flows originating only in the Piedmont, begin their fall zones at elevations around 50 feet and drop to sea level very quickly, so the zones are much shorter, measuring in yards rather than miles.

For a fuller picture of the Chesapeake’s fall lines, it’s worth remembering the forces that shaped these river systems. Over the past 500,000 years, the Chesapeake watershed has gone through three periods of glaciation in which sea level dropped as much as 500 feet while the climate turned cold and locked up water in glaciers to the north during an Ice Age.

In these times, the main river (today’s Susquehanna) flowed from the edge of its glacier in today’s central New York and Pennsylvania. Bounded to the west by the Appalachian and Blue Ridge Mountains and the

Piedmont plateau, it ran south and east, gathering all of the other Chesapeake rivers as tributaries in its lower reaches. On the east, its boundary was the growing spit of coastal plain land built from the Atlantic’s longshore flow and sediments from the Hudson and Delaware rivers.

We know that spit today as the Delmarva Peninsula. It is built on coastal plain gravel, sand, and mud, so its rivers don’t have strict fall lines with rocky rapids. As they carry rain off higher ridges of land, though, their beds reach sea level at the points noted above.

Between its western and eastern shores, the big river cut its channel far across the continental shelf to reach the Atlantic in the region of today’s Norfolk Canyon. During this time, all of the rivers carved deep channels into their geologically diverse beds.

Around 300,000 years ago, the climate warmed up, the glaciers melted and sea level rose, backing up into the big river’s valley to create an estuary of roughly the same length as today’s Bay. Its mouth appears to have been perhaps forty miles further north, because the Delmarva Peninsula had not grown as far down the coast. In (long) time, sediment filled that estuary. Another Ice Age and thaw around 150,000 years ago created another Bay with a mouth about twenty miles north of the current one. It too filled in before another Ice Age dropped sea level again. Our Bay began forming about 18,000 years ago, as that most recent Ice Age thawed. It reached its current basic shape about 3,000 years ago, though we know all too well that that shape continues to change before our very eyes.

The story of our rivers’ fall lines carries an important lesson for us. Our Chesapeake is a dynamic system, changing subtly by our quick-time standards, but inexorably. There’s an old saying that “Mother Nature still makes the rules, and She always wins.” We do well to learn to work with her, rather than against.

Note: If you’d like to read a good non-technical summary of this process, check out Chesapeake Quarterly, the magazine of the Maryland Sea Grant Program, at chesapeakequarterly.net. Look in the CQ Archive for Volume 10, Number 1 (2011), The Bays Beneath the Bay.