34 minute read

REVIEW Worlds collide with DaNang Kitchen’s Vietnamese brunch

Chef Sydney Le’s steak and egg skillets fit right in—somewhere between breakfast and lunch.

By MIKE SULA

There’s no such thing as brunch in Vietnam.

That’s according to Jeanette TranDean of the Vietnamese-Guatemalan pop-up Gi ng Gi ng. “It’s eat morning or eat night,” she tells me.

Nevertheless, Argyle Street’s DaNang Kitchen recently started offering a “Vietnamese brunch,” featuring a few relatively uncommon dishes that can address a Western appetite for hangover-mitigating egg skillets.

I was alerted to this a few months ago by reader Andy Rader, who always has a keen eye for uncommon, new-to-Chicago dishes. What made me sit up straight was the bánh mì chảo, in this case a cast-iron skillet housing stirfried ribeye, fried eggs, a slab of the emulsified pork sausage chả lụ a, a gob of livery pâte, a bone marrow luge, and cherry tomatoes, all with a crispy baguette on the side. Sometimes you see English-speaking food writers refer to this as the Vietnamese full English breakfast, and yes, that’s lazy and inaccurate, but it’s not hard to see why.

By chance, I had just sought out a version of this dish on a recent trip to San Jose, California (home to more Vietnamese people than any city outside of Vietnam). The tiny strip mall food court stall Bò Né Phú Yên had just been written up by the San Francisco Chronicle, and the owner told me the crush of new customers meant he had to suspend his entire menu—except for his signature, which he serves on a cast-iron plate shaped like a cow.

So I was thrilled to see something like this appear in Chicago, though Tran-Dean reminded me that she and David Hollinger served a version of it at the very first Monday Night Foodball. At a recent Loaf Lounge pop-up, Tran-Dean and Hollinger also served a version of the pork meatball dish xíu m ạ i—which is also on the brunch menu at DaNang.

In Vietnam, nobody eats these things for breakfast, says Tran-Dean. Breakfast is for ph ở and other noodle dishes. Xíu m ạ i and bánh mì chảo are all-day snacks.

Nevertheless, I had to get them in front of me, so I planted myself at a sidewalk table in front of DaNang at the ungodly hour of 11 AM and ordered the full Vietnamese brunch menu.

DaNang’s steak and eggs certainly scratched an itch; the whole set is plated in the skillet with sweet soy that mingles with the runny yolks and housemade livery pâté (chef-owner Sydney Le’s mom’s recipe) into a saucy alloy that’s perfect for baguette dredging.

But the xíu mại was the standout—a pair of super-soft pork meatballs in a sweet and sour tomato gravy, each orb containing a perfectly gooey quail egg to complement the sunnyside-up cackleberry.

The only other item on DaNang’s brunch menu is xôi mặn, an infinitely variable, savory sticky rice snack, here served with chả l ụ a, shredded Chinese sausage, omelet strips, pork floss, and more pâté. It’s another typical all-day snack, but it somehow seems right in the late morning with an iced egg co ee and Vietnamese steak and eggs.

Le tells me she’s had so many requests from people who have eaten bánh mì ch ảo in California but couldn’t find it here that she had to figure out a way to get it on her menu. Brunch seemed obvious. “I think in the United States we learn to combine good things from di erent cultures,” she says.

But the fact is you can eat these dishes pretty much any time of day at DaNang Kitchen, and since they recently started offering it every day except Tuesday (closed), that makes Vietnamese brunch an 11/6 a air.

@MikeSula

The facade slipped off, & the boy wept alone.

A shriek too loud for his young eardrums

He ran only to hide & never to find a new home. He ran for so long, he forgot what he was running from. Was it lies or was it truth?

He Couldnt distinguish the two.

Like how scandalous whispers blend in the wind

Or how insecurities stem from within

With waterfalls in his tear ducts

Trying to see clearly but Its so blurry nowadays. He Yearned for empathy

But received crocodile tears instead. He wished for peace

But Folks still wanted off with his head. Who were the voices criticizing him?

Why did their words cut so deep?

The crowd in his head drove him away from where he was meant to be. -Happy & free.

By Cristian Sanchez

Cristian Sanchez is a multidisciplinary-latino artist from Logan square, whose work explores the modern day human condition, spiritual growth, & the gritty journey to actualization. Cristian juxtaposes inspiration from his upbringing though his immigrant parents, the radical change/gentrification of his community, & his longing for a resilient community.

Poem curated by Chima “Naira” Ikoro. Naira is an interdisciplinary writer from the South Side of Chicago. She is a Columbia College Chicago alum, a teaching artist at Young Chicago Authors, and South Side Weekly’s Community Builder. Alongside her friends, Naira co-founded Blck Rising, a mutual aid abolitionist collective created in direct response to the ongoing pandemic and 2020 uprisings.

A biweekly series curated by the Chicago Reader and sponsored by the Poetry Foundation.

Free Programming from the Poetry Foundation!

Hours

Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday: 11:00 AM–4:00 PM

Thursday: 11:00 AM–7:00 PM

Performances of No Blue Memories: The Life of Gwendolyn Brooks

Written by Chicago poets Eve L. Ewing and Nate Marshall, No Blue Memories is a uniquely staged retelling of Brooks’s life using simple, illuminative paper-cut puppetry by Manual Cinema set to music composed by Jamila Woods and Ayanna Woods.

Thursday, May 18, 6PM, Harold Washington Library

Gwendolyn Brooks Panel: Reflecting on a Chicago Legend

Join us for a roundtable discussion of legendary Chicago poet Gwendolyn Brooks and her book Blacks with Nora Brooks Blakely, Haki R. Madhubuti, and Kelly Norman Ellis.

Thursday, May 25, 2023, 7PM

Learn more at PoetryFoundation.org

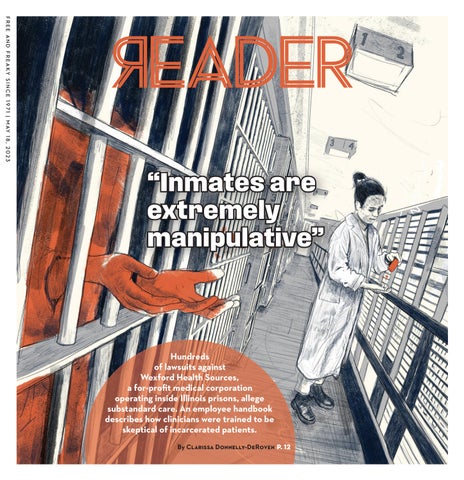

Prisons

Hundreds of lawsuits against Wexford Health Sources, a for-profit medical corporation operating inside Illinois prisons, allege substandard care. An employee handbook describes how clinicians were trained to be skeptical of incarcerated patients.

By CLARISSA DONNELLY-DEROVEN

Content note: This story contains descriptions of deaths in prisons, including suicide.

On July 16, 2010, at 11 PM, Jeremy started sweating. He walked to the health-care unit inside the Lawrence Correctional Center, a medium-security men’s prison in southeast Illinois, where he was serving a 14-year sentence. The facility sits about 90 minutes from Terre Haute, Indiana, where the federal government conducts executions.

Jeremy told the health-care workers inside the prison clinic that the left side of his chest hurt. Tammy Troyer, a nurse at the facility, took his blood pressure. It was an alarmingly high 172/105. Doctors consider healthy blood pressure to be below 120/80.

Troyer picked up the phone and called Dr. James Fenoglio, Lawrence’s medical director, for a consultation. Thirty minutes later, the two providers sent Jeremy back to his cell. They did not listen to his chest, o er him aspirin or oxygen, or take a full medical history, according to a complaint Jeremy’s family filed in federal court in 2011. (The details of Jeremy’s story come from that complaint. In their response to the complaint, Fenoglio and Troyer denied the allegations and said Jeremy’s blood pressure lowered su ciently before they sent him back to his cell.)

Jeremy stayed in his cell for the next hour, but by 12:30 AM he hobbled back to the clinic.

He told Troyer that he felt a squeezing sensation in his chest and that his pain was an eight out of ten. Troyer took his blood pressure again. It was 188/112. She called Fenoglio again. After another hour passed, the two sent Jeremy back to his cell.

Two hours later, at 3:20 AM, Jeremy returned to the clinic for a third time. “My chest still hurts on the left side,” he said, according to the federal complaint. He told them he was still in pain and short of breath. This time, Troyer did not call Fenoglio and after a ten-minute visit, she sent Jeremy back to his cell. The next morning, Jeremy was dead. An autopsy concluded he died of a heart attack.

Troyer and Fenoglio both worked in a prison operated by the Illinois Department of Corrections—private prisons are illegal in the state—but neither of them was employed by the IDOC. Instead, they worked for Wexford Health Sources, a privately held for-profit medical corporation based near Pittsburgh. Troyer and Fenoglio did not respond to requests for comment sent to personal and professional social media pages.

Over the last decade, with very few exceptions, Wexford employees have provided all health care to incarcerated people in Illinois. Between 2011 and 2021, Illinois paid the company nearly $1.4 billion of taxpayer money to provide medical care inside every prison in the state. And though the company’s contract was set to expire in 2021, it’s been extended multiple times since, to the tune of nearly $418 million.

Wexford has worked with the Illinois state prison system since the 1990s. The company also controls the medical systems of at least 120 prisons and jails in states including New Mexico, Arizona, Alabama, Virginia, West Virginia, and New Hampshire. “This makes us large enough to e ciently deliver the services required by our clients, yet not so large that we cannot respond quickly to their needs and concerns,” Wexford wrote on its corporate website in 2021, which has since been redesigned. “Incorporated in 1992 for the sole purpose of servicing correctional facilities, our unique combination of experience, resources, reliability, and responsiveness enables us to provide clients with quality, cost-effective inmate health services.” The “clients” Wexford mentions are not the incarcerated patients, but the prisons or jails with whom it contracts. Some states, like Florida, have terminated their contracts with Wexford amidst allegations of shoddy care. Wexford has denied these allegations.

Wexford has hired 123 lobbyists across the country over the last 16 years, 71 of whom currently operate in Illinois, according to Open Secrets, a national organization that tracks campaign finance contributions. The company disputes these numbers. Wendelyn R. Pekich, Wexford’s vice president of strategic communication, said Open Secrets’ lobbyist count is inaccurate because it includes lobbyists who work for a firm, as well as firm subcontractors, neither of whom necessarily lobby for Wexford.

Pekich pointed to the company’s lobbying page on the Illinois secretary of state’s website as a more accurate picture. It lists three lobbying firms that work on behalf of Wexford: Advantage Government Strategies LLC, Phelps Barry & Associates LLC, and Stricklin & Associates.

State and federal prisons are legally required to provide quality medical care to incarcerated people. When states like Illinois turn that obligation over to private for-profit correctional medicine companies like Wexford, there is far less transparency about how that health care gets delivered. In court, Wexford often argues against the disclosure of its training manuals and other policy documents that describe the day-to-day conduct of its sta inside these public institutions, arguing that those records are proprietary and confidential. Publicizing them, the thinking goes, would put the company at a disadvantage relative to fellow correctional medicine companies that it competes against for contracts. The company also extends that argument toward disclosing profits. When asked by the Reader if their profits are in the million or billion-dollar range, the company declined to answer, saying it was Wexford’s “proprietary financial information.”

Wexford connected the Reader with Andy DeVooght, an attorney who works as an advisor in Illinois for the company, to answer questions about Wexford’s work inside prisons. Quotes and comments attributed to Wexford henceforth come from him. During the hourlong conversation, Wexford denied all of the allegations against the company described in this piece.

While Wexford is unwilling to disclose much information publicly, the Reader obtained some of the company’s internal documents through an incarcerated source: a clinician handbook for company employees from 2008 and guidelines Wexford gives to outside physicians who see incarcerated patients for specialty care. Wexford would not confirm or deny the authenticity of these documents. The company did confirm that clinician handbooks and guidelines are not available to the public.

It is unclear whether the 2008 handbook reflects the current policies Wexford sta follow in Illinois prisons.

Both internal documents advise clinicians to be skeptical of their incarcerated patients. The manual describes the people inside as “patient-inmates” and bluntly writes “inmates are extremely manipulative” and “inmates may exaggerate their conditions.”

The documents advise clinicians that when interviewing patients about health problems, “be willing to accept their claims and descriptions, but maintain a healthy amount of doubtful suspicion.”

These documents, along with settlement agreements the company entered into with Illinois prisoners and their families following lawsuits that alleged Wexford provided them substandard medical care while they were incarcerated, begin to paint a picture of how the company operates inside Illinois prisons.

Between 2011 and 2020, the company paid out $20 million dollars in 206 of these confidential settlements in Illinois, according to an analysis of the settlement agreements by the Reader

In none of the agreements does Wexford admit wrongdoing or neglect by its employees. The settlements contain strict nondisclosure agreements. Most stipulate that if the recipient discusses the settlement, the company can attempt to sue them for breach of contract to recoup the entire amount awarded.

Two years after Jeremy’s death, Wexford paid his family $150,000. But they can’t talk about it. “There are confidentiality clauses that will not allow me or my client to speak to you,” Jeremy’s family’s lawyer told me in an email. “I wish we could help, but the releases forbid it.” Wexford cited the same confidentiality clauses and declined to comment on the settled cases.

For this reason, Jeremy is a pseudonym. All of the details written here about him—and everybody else who received a settlement— come from court documents and public records. But because nobody gave their consent to have these highly personal, and sometimes traumatic, medical details shared, we’re concealing their identities unless explicitly noted.

In the winter of 2020, I sent a public records request to the Illinois Department of Corrections. I wanted to see every out-of-court settlement (meaning agreements between the parties to end a lawsuit without the court’s involvement) that Wexford had entered into with people incarcerated in Illinois prisons between 2011 and 2020. These documents became accessible to the public nearly two years earlier thanks to the Illinois Times, Springfield’s alt-weekly, which sued IDOC.

It all started when a reporter at the Illinois Times grew curious about the case of Alfonso Franco, who died in prison in 2012 from cancer. In 2015, the reporter sent a public records request to IDOC for any settlement agreements relating to Franco’s death that involved Wexford. IDOC told the paper that Wexford had those documents and that the company was refusing to turn them over.

Wexford argued the documents the paper requested were “confidential in nature” and, therefore, not a public record. The case wound its way through the courts until it arrived at the state supreme court. In 2019, the court ruled that it did not find the company’s argument persuasive. Because IDOC contracts with Wexford to provide medical care to incarcerated people on its behalf, the court said, the settlement agreement “directly relates to the medical care that Wexford provided to an inmate. Thus, it is a public record of the DOC for purposes of FOIA.” prison are much more likely to have hepatitis, high blood pressure, asthma, cancer, and other chronic conditions than the free population. While most of these ailments are manageable when attended to, they can be deadly without proper care.

Despite the court ruling, the Illinois Times still waited months for the documents to arrive. The paper first published a story in September 2020. At that point, they’d received about 20 settlements, which showed Wexford had paid $1.2 million in settlements since January. In November, after a court-appointed independent monitor published a report about the quality of care in Illinois prisons, the paper reported that Wexford or its insurers paid about $17 million in settlements since 2011.

A few months later, the documents I obtained through a public records request showed an even higher sum. I spent months matching the settlements with their corresponding federal court case. I calculated how much money Wexford spent and analyzed the court records to see if any patterns existed: Did some facilities see higher numbers of settlements than others? Did incarcerated people struggle to obtain specific types of medical attention—dental care, for example? What did the relationship look like between settlement amount and race? The analysis does not include monetary awards from cases that went to trial, only payments the company or its insurers gave to incarcerated persons or their families between 2011 and 2020 in exchange for dropping a lawsuit.

Inside Wexford’s 2008 provider handbook, the company explains that providers of prison health care are prohibited from displaying “deliberate indi erence” to an incarcerated person’s medical needs. The Supreme Court first defined “deliberate indi erence” in the 1994 opinion Farmer v. Brennan. The court ruled that individual prison o cials could be held responsible for Eighth Amendment violations if an incarcerated person could prove that they faced a serious risk to their health or safety, and the prison o cial knew about it and didn’t do anything to help.

“Incarcerated patients are wards of their respective state or county with no alternatives for care other than services the institution provides,” the company writes. But “the state does NOT have a responsibility to provide a service simply because an inmate demands it be done. Nor does the state have a responsibility to CURE, only to appropriately diagnose and treat. . . . Medical service is NOT the mission of corrections (though the institution is required to provide such). Medical care is a supportive service.”

Later, in a section of the handbook that describes “health care roles” in the prison, Wexford explains that at the top of the prison hierarchy is the warden. They are “responsible for everything that happens in the unit. Although on occasion a medical decision may be in conflict with [the warden’s] express wishes, most decisions should respect [the warden’s] management responsibility.”

“Security is the prime objective of all prison operations,” Wexford writes. “And you are expected to understand and respect that responsibility.” plainti s raised in the lawsuit.

The highest settlements didn’t always go to those who were the sickest, or even those who died.

Still, many families continue to argue that the company did not do enough to monitor and protect their loved ones. The family of Jacob, a man who died by suicide in prison under Wexford’s care, claimed in their lawsuit, “A cost-saving policy of understa ng and an inappropriate reliance on medications designed to quiet and restrain rather than treat mentally ill inmates left [Jacob] without treatment at a critical period of his mental illness.”

The largest settlement in the public records I received from 2011-2020 was for $5,975,012. It went to the family of Manny. Manny came to Graham Correctional in 2014 with a disability and he fell into a coma just a year later. His family alleged in their lawsuit that the prison didn’t respond to his chronic health needs.

The second largest settlement went to Robert. In 2007, Robert was incarcerated at the Northern Reception and Classification Center at Stateville. According to allegations in federal court records, prison officials and medical providers knew Robert had epilepsy, and prescribed him seizure medication: two tablets to be taken once a day. According to the suit, administration records show that nobody gave Robert his medication for 11 days. On the 12th day, a nurse found him unresponsive in his cell. He was transported to the hospital, where doctors diagnosed him with a ruptured brain aneurysm, the result of seizures he had while at the prison. Robert suffered permanent brain damage. Settlement documents show his family received about $3 million.

During the ten-year period in which it held the $1.4 billion contract in Illinois, Wexford was required to pay for any o -site care that a patient received at a facility other than a hospital—an MRI or an evaluation by an oncologist, for example. The company denies that it factored into their decision to approve or deny o -site care.

“I understand in the abstract if you start putting these pieces together—like the contract is worth X, and they’re a private company, and you have utilization management—but it’s really gluing things together that don’t go together,” DeVooght, the Wexford advisor, said. “When you look at them, the actual facts, about each of those points, they don’t support the way they’re being used.”

Utilization management is the process private medical companies like Wexford use to determine whether a procedure is medically necessary, and whether to pay for it or not. Wexford said that when it used utilization management in Illinois, its approvals for off-site care were above 80 percent, though it did not provide data for the Reader to independently verify.

The company explains in the handbook that a prison must provide incarcerated people with medical care “that is ‘equal to that available in the local community.’” But, this doesn’t mean Wexford or its doctors have “a mandate ‘to cure.’” Rather, they write, “it is a mandate requiring problems be addressed in an appropriate and professional manner.”

“Although a program of comprehensive medical care is required, not every diagnosis mandates treatment, nor is repair done on every existing condition,” the handbook says. Wexford’s care philosophy, according to the handbook, is to operate “somewhat like ‘workers compensation.’” If a person gets sick because of their incarceration, Wexford is required to treat them. But, if they come in with a chronic condition, these “require monitoring only.” Numerous studies show that people in

Out of the 206 settlements, seven followed deaths people suffered while in the company’s care. Those seven totaled about $4.5 million, and the median amount received was $250,000.

Three of those seven people died by suicide, and according to complaints filed in federal lawsuits, all were known by Wexford sta to su er from mental health issues.

Wexford said settlements are based on the specific facts and circumstances in a particular case. The company pointed to the 2022 federal appeals court ruling in Rasho v. Je erys, a case about the state of mental health care in Illinois prisons. The district judge ruled against IDOC and Wexford, declaring them to have been “deliberately indi erent” to incarcerated people’s psychiatric needs, primarily through their failure to su ciently sta mental health units. But the appeals court reversed that decision, writing that the state and Wexford “took reasonable steps” to fix many of the problems—including the sta ng issues—the

Though the company rejects this characterization, attorneys who’ve sued Wexford argue that Wexford’s contract with the state introduces incentives for it to spend as little money as it can on care. “Their business model is to receive a flat amount of money and then profit o of any money that they are not forced to spend,” said Sarah Grady, formerly the lead attorney at the Prisoners’ Rights Project at the civil rights firm Loevy & Loevy in Chicago. She has since begun her own independent prisoners’ rights legal practice.

In its 2008 employee handbook, the company gestures toward the role cost plays in providing care: “A criticism frequently directed toward private managed care companies like Wexford is that services are withheld to improve profits. Similar criticism has been directed at the medical industry in general, implying that cost—money—should never be a consideration in regards to providing medical care. Cost has always been a consideration in treatment.”

During its decade-long contract, Grady said Wexford had numerous “gatekeepers” who worked to prevent o -site care from happening. To receive care somewhere other than the prison, the facility’s medical director (who was a Wexford employee) first would have to give their approval, and then the request would go to the company’s regional medical director, and then to the medical director who works in Wexford’s corporate office in Pittsburgh.

If a patient was allowed to see an off-site doctor, the 2008 handbook notes that physicians who are Wexford “consultants” should be considered first. It is unclear if these “consultants” received any payment from the company, though they did receive a document with guidelines on how to care for “patient-inmates.” Those guidelines advised physicians not to tell patients when their next appointment is, inform patients about their specific diagnosis, give patients any documentation about their treatment plan, o er patients any “equipment or supportive aid,” or attend to any medical problems besides the one they’d been sent for.

“DO NOT EVER explain symptoms you would expect to see to confirm a diagnosis to an inmate,” the company writes. “If you should, those symptoms will likely be present with the next visit.”

The skepticism the company advises cli- nicians to have of their patients extends into their treatment recommendations. In the documents, Wexford advises that because many patients have substance use disorders, doctors should think twice before prescribing pain medication. Also, they explain, physical therapy is “often abused” by incarcerated patients, and they warn doctors to be cautious when giving a patient a prosthetic limb. “Just remember,” Wexford writes, “our patients are often very skilled, and can make serious weapons from innocuous materials.”

The 2008 handbook also gives Wexford sta doctors license to ignore recommendations of outside clinicians if they don’t fit within the confines of prison health care.

“It is important for you to inform your consultant of the patient’s history, physical and laboratory findings, and your reasons for referral. You also have a legitimate right to disagree with a specialist’s position,” the company writes. “Often circumstances of the confinement or security are not understood by the consultants. You are expected to understand these issues and work around or through them. DO NOT BLAME THE PROBLEM ON THE DEPARTMENT/COUNTY—simply explain that you have policy responsibilities that must be addressed.”

Grady, the attorney, explained that in her experience the people in Wexford’s corporate office who were tasked with approving or denying outside care often didn’t have access to a patient’s full medical chart. “They receive whatever is given to them,” she said. “We have seen in some cases where that becomes a justification for delay or denial of care.” The company, though, would rarely write that they were denying someone care, she said. “Instead, they would say things like, ‘We need some more information. Why don’t you come back in a few months after this happens?’ And that thing would be relatively meaningless, and then when that comes up, something else needs to be done and something else. And so people will be shu ed around and around in the system, which effectively denied them care, but it was not the sort of smoking gun that you could point to the page and say, ‘Look! They knew he had cancer and they said don’t send him!’”

Wexford denied these allegations and declined to comment on the specifics of the company’s utilization management policy. But Jack had an experience much like the one Grady described. His family received $130,000 in 2016, the smallest sum following a death in the settlement documents reviewed.

Jack was incarcerated at the Graham Correctional Center, a medium-security prison near Saint Louis. According to the legal complaint filed by his family, in the two years before his death, he was undergoing dialysis treatment.

Between November 2012 and January 2013, more than six tests of Jack’s blood, analyzed by the University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign medical center, showed that he had an infection common in dialysis patients. While treatable, the infection can lead to sepsis and death without proper attention.

Jack’s test results were sent from the university medical center to his Wexford doctor and an outside nephrologist. The nephrologist did not work for Wexford but was overseeing Jack’s dialysis, according to the complaint. As the employee handbook explains, even when a patient is sent to an outside specialist, the decision-making power remains with the company doctor since “the specialist does not (or may not) understand the special requirements of the correctional setting.”

During the two-month period, the nephrologist requested that Jack’s blood be taken again and retested. But even though each of the tests showed the same infection, he was not prescribed any treatment. Jack died of sepsis in February 2013, three months after the first test showed the infection.

In 2019 the Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation put the Wexford doctor on probation following another lawsuit against them and the next year put their medical license on “permanent inactive status” after they failed to take a required exam.

Allegations of mistreatment and poor medical care from Wexford employees aren’t limited to the 206 who won settlements from the company. I sent 12 letters to incarcerated people—selected at random—inside Illinois prisons to ask about their experience with medical care. With such a small sample size, I didn’t expect to hear anything back. I was wrong.

At Lawrence Correctional, especially, word got around. My letter was photocopied and distributed widely. I received ten letters from incarcerated people, detailing allegations of medical mistreatment and neglect in that prison: a transwoman who said she’s denied gender-a rming care and psychiatric treatment; a man who cannot access services because he only speaks Polish and there aren’t translators; another man who was prescribed physical therapy for a back injury but never received it. Wexford declined to comment on all active cases but said that as it relates to gender-a rming care, the company works closely with the IDOC to implement its policies.

James Sevier (his real name) was transferred to Lawrence Correctional from Stateville in December 2021. He said that when he arrived, prison sta took away his compression stockings and ankle support because he didn’t have a permit. Sevier wrote to me that he needs those medical devices to manage a chronic injury, but Wexford employees at the facility wouldn’t give them to him.

He said a nurse examined him but didn’t write him a permit for the equipment because only a doctor had that authority. Sevier submitted a grievance to the prison and asked to be seen by a doctor. A counselor at the facility responded in writing, saying that Sevier’s complaint was warranted. “Lawrence [Correctional Center heath-care unit] + Wexford Health Sources does not have a full time physician on site to treat and see patients. Wexford Health Sources Inc has failed to provide physician as stated in IDOC-Wexford Contract.” Wexford declined to comment on Sevier’s case.

Terry Dibble (also his real name) responded to my letter too. He’s 49 years old and incarcerated at Shawnee Correctional near the Kentucky border. For about a decade, Dibble has had a bump on the base of his skull. Over the years, he wanted to see a doctor or a nurse to get the lump examined, and maybe removed, so he put in several requests to the prison health-care unit. But each time, he said a provider would use a finger to poke the growth and tell him it was a lipoma, a fatty noncancerous tumor.

“I asked about getting it removed and they said, ‘Well, our policy is that if it’s cosmetic, we’re not going to do anything with it, unless it’s causing you severe pain,’” Dibble told me over the phone. “I always told them it was definitely painful. For years, I complained.”

In summer 2020, Carissa Luking, a nurse at Lawrence Correctional Center, told Dibble she put in a request to Wexford to ask for approval to remove the growth, according to a lawsuit he filed in July. A week later, Luking called Dibble to the health-care unit. She told him she was going to remove his lipoma. He was taken aback but remembered her saying she had done this several times before in her private practice.

In his lawsuit, Dibble recounts that he laid face down on an exam table. Luking injected him with a numbing agent and cut into his scalp. Dibble couldn’t feel the incision, but he did feel something warm drip down his neck. It was blood. It gushed from the back of his head and pooled on the ground.

According to his federal complaint, Dibble said Luking told him there would be a lot of bleeding because the numbing agent she used did not have a coagulant to make the blood clot. “I’m thinking to myself: OK. Alright. She knows what she’s doing,” Dibble told me on the phone. “She’s done this before.”

Luking talked to Dibble as she cut, commenting about how mad the incarcerated cleaning workers were going to be that they’d have to clean up so much blood, according to his court filing. Luking showed Dibble the chunk she’d cut out of his head. Not usually one to be squeamish, he felt his belly flop.

The tissue Luking showed wasn’t yellow like the fatty tissue of a lipoma. Instead it was pink—the color of muscle tissue. Dibble told Luking that, but she insisted he was wrong. He sat quietly as she stitched him up. She then destroyed the “lipoma” because she didn’t see a need for a biopsy.

Two weeks later Lawrence’s medical director, Lynn Pittman, called Dibble into her o ce. She said to him, and wrote in his medical records, that the “procedure was unauthorized” and “botched.” In the time since the excision, Dibble had assumed as much: the lipoma was still on his head, and his scalp hurt tremendously.

Pittman referred Dibble to a general surgeon to have the procedure repaired. In her continued from p. 15 request for off-site care, which is called the Medical Special Services Referral and Report, she wrote: “NP Luking . . . performed an unauthorized, failed lipectomy on the [inmate] in the [health-care unit]. She apparently cut through the lipoma to the muscle layer under the scalp and blunt dissected a segment of muscle from the [inmate’s] head. The lipoma is still present [and the inmate has] increased pain from the botched procedure. General surgery needs to evaluate [the] lipoma and other possible damage.” Wexford declined to comment on Dibble’s case. Luking and the other defendants have not yet filed a response to the lawsuit.

A section within Wexford’s employee handbook states that doctors should “not criticize either medical or correctional staff in an individual’s medical chart.” Pittman no longer works for Wexford. Luking remains a nurse at the prison; she did not respond to a request for comment sent to her professional LinkedIn account.

Twenty million dollars in settlements. What does that mean?

“It’s a big number, obviously, for most people,” said Alan Mills, the executive director of the Uptown People’s Law Center. He’s sued Wexford numerous times, including a class action lawsuit in 2010 that led to the imposition of a federal court monitor to oversee the medical care provided inside Illinois’s prison system. But for Wexford, “It’s a rounding error in their budget. It has no effect whatsoever on them,” he said, noting that Wexford’s tenyear contract in Illinois was worth $1.4 billion.

“Some of the personal injury lawyers and other people in town who specialize in this kind of work, they can get [$20 million] in one case.”

Mills continued. “And of course, it’s not $20 million divided among 207 cases from Wexford’s point of view. It’s divided among all the cases that were brought up by prisoners, which is many times that 200,” he said. “They have risk assessment people, and I’m sure that they find calculations saying that, ‘It’s cheaper to pay out this than it is to increase the average level of service.’”

Wexford denied thinking “about individuals and human beings as rounding errors in a budget.”

The 2010 class action Mills filed against Wexford and the Illinois Department of Corrections argued that poor medical care inside of the state’s prisons caused the incarcerated plainti s needless pain and su ering. In 2017, a judge ruled that the class action lawsuit could proceed, finding the plainti s had “su ciently alleged that Wexford and the Illinois Department of Corrections have provided deficient medical care on a systemic basis.” In 2019, the court entered a consent decree jointly proposed by the parties to settle the class action lawsuit. Ideally, it would’ve meant individual prisoners would no longer be responsible for filing suits, one by one, to address systemic problems.

The main part of the consent decree involved the appointment of an independent monitor to oversee the overhaul of the prison health-care system. In 2019, a judge appointed Dr. John Raba, the former chief medical o cer for the Cook County Health and Hospitals system, as the monitor. Since then, he’s filed six reports, the most recent in March 2023. According to all of them, the quality of the health care provided inside Illinois prisons has yet to markedly improve.

In his September 2021 report, Raba noted three doctors who he had concerns about. The state permanently suspended one physician’s license, and Wexford fired the other two doctors in July 2021. Movement from a state licensing board was notable, considering that much of Wexford’s litigation strategy appeared designed to avoid implicating its doctors, according to Grady.

The Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation oversees the licenses of nurses and doctors and is empowered to investigate allegations of misconduct. The department also requires insurance carriers and hospitals to report any settlements or final judgments in a negligence case against a physician. These documents are included on a physician’s profile on the agency’s website.

“Hospitals are also required to report to the [Department of Financial and Professional Regulation] if any physician’s hospital privileges have been restricted or terminated or if the hospital is self-insured and paid the judgment or settlement,” said Paul Isaac, a spokesperson for the agency.

“What you will see if you review the public dockets is that often to reach a settlement, the individual doctors will be dismissed before there is an agreement or as part of the agreement,” Grady, the prisoners’ rights attorney, said. “It allows these doctors to say, ‘I don’t have to report any malpractice payments because I’ve never paid one because I’ve never settled the case. I just happened to be dismissed right before the case reached settlement.’”

Wexford denied the allegation. “There’s no secret strategy,” DeVooght said. “When we’re recruiting people, we need to be able to tell them, ‘You do a good job, we’re gonna stand behind you.’ How else are we going to get people to be willing to perform the care that we need them to perform?”

In the same report from September 2021, Raba indicates that the Illinois Department of Corrections is nowhere near implementing a systematic solution to its health-care issues in prisons. Notably, he explains that the IDOC did not send documentation he requested regarding the credentials of physicians and other medical professionals who work in the prisons, as well as any records of sanctions or disciplinary actions against them. In the documentation they did send him, he notes that six of the 26 physicians working in the prison system lack the credentials required of them by the consent decree.

Wexford said that it is committed to working with IDOC to complete a valid implementation plan to improve health-care services, as required by the consent decree. In August 2022, a federal judge found the IDOC to be in contempt of the court due to its failure to make most of the changes mandated by the decree and the monitor.

While Wexford employees can’t be fired by the Illinois Department of Corrections, “The state of Illinois retains the ability to ensure that Wexford is adhering to its contract,” Grady said, referring to the language within the contract requiring that the company provide adequate health care.

Also, prisons are closed facilities, meaning that the Department of Corrections can prevent someone from entering the facility if they so choose. “It’s a position that the Department of Corrections has almost never taken,” Mills said. “When they do it, it’s usually for security reasons—that is, a doctor is found to be doing something that jeopardizes the security [of the facility], rather than providing terrible medical care.” IDOC did not o er a response to this allegation.

Incarcerated people and their families may accept out-of-court settlements rather than going to trial for a few reasons. Many laws make it very di cult for prisoners to win medical lawsuits against the facilities that incarcerate them. A person has to first prove that the prison showed “deliberate indifference” to their serious medical need, which requires proof that prison o cials both knew about the need and chose to ignore it.

“There’s case law that’s specifically designed to make it di cult to hold Wexford as a corporation to account,” Grady said. “It’s virtually impossible unless someone has representation. And Wexford knows all of that.” Wexford denied the allegation.

Mills mentioned a recent case where an Illinois prison denied a man, who was close to his release date, cancer treatment. Unlike most similar cases, the man took his case to trial. He had legal representation, and ultimately, he received a multimillion-dollar award.

But that’s far from the norm. Most prisoners can’t a ord representation, and even if they find someone who will take on their case, another issue arises. “Prison cases, unlike cases on the outside, generally don’t have any outof-pocket loss. It’s almost impossible to prove loss of future wages for a prisoner because the very fact that you’ve been in prison so much depresses your earning ability afterwards,” Mills said. “Plus, medical expenses are all paid for by Wexford, so you haven’t got any claim for those.”

Winning an award at trial is complicated for incarcerated people because it depends on a jury recognizing and valuing their pain and su ering. “And there are a lot of jurors,” Mills noted, “who say, ‘If you’re in prison, you

Hands-on training for a lifesaving career.

Malcolm X College’s accredited Nursing program prepares future nurses to provide quality care. With hands-on training in our state-of-the-art virtual hospital and connections at area hospitals, you’re set up to lead and succeed in your career.

• Tuition-free opportunities for eligible students

• Financial, academic, clinical and career support available

• Opportunities for dual enrollment: earn your associate and bachelor’s degrees at the same time continued from p. should su er. Who cares?’”

For people who are still incarcerated, any money can feel like a significant win, even if the amount might seem meager in comparison to the level at which they su ered. “Five thousand dollars doesn’t seem like a lot for an injury. On the other hand, if you’re in prison, and you get $10 a month as your stipend for working a job,” Mills said, “$5,000 is 500 months of work.”

Wexford knows that it’s in a position of power in these negotiations. Grady said she believes that “Wexford has made an intentional choice not to provide a constitutionally adequate level of care in the hopes that it’s too expensive or even impossible for them to be held to account for that decision.” Wexford denied this allegation.

In the documents I reviewed, 37 people received under $1,000 in their settlement. The lowest settlement amounts sometimes correlate with the seriousness of the medical problem—such was the case for a man who has glaucoma and received $400 from Wexford after he sued the company for failing to give him bifocals.

But other times, it doesn’t. One man, for example, received $500 following his lawsuit that argued Wexford failed to treat a rash that had been bothering him for nearly a year. By the time he got a diagnosis, the doctor told him the rash was a permanent fungus he would need to learn to live with.

One clear pattern, however, is that incarcerated Black and Latino people, on average, received fewer settlement dollars from Wexford than incarcerated white people. Wexford denied that race factors into their calculations when determining settlement o ers.

Looking through prison population datasets, which are published biannually by the IDOC, I determined the race of 170 of the 182 people who received settlements from Wexford (there were 206 total settlements, but 11 people received multiple settlements for di erent cases).

Of those 170 people, 69 percent were Black, 19 percent were white, 11 percent were Latino, and less than 1 percent were Indigenous. Collectively, they received about $18.7 million in settlements.

But the settlements include outliers, or amounts that differ dramatically from the norm, that skew the analysis. The largest settlement in the bunch, for $5.9 million, went to the family of Manny, the Latino man who, according to the family’s lawsuit, fell into a coma after the prison neglected his chronic health needs. There are four other outliers: $1.5 million, $3 million, $2.3 million, and $900,000. All of those settlements went to Black plainti s. They, in fact, represent 72 percent of all settlement money that went to Black plainti s.

With the outliers removed, there’s about $5.1 million remaining, which was distributed among the remaining 165 plaintiffs. Black plainti s received about 48 percent of those settlement dollars, white plainti s got about 28 percent, and Latinos received just 2.5 percent.

The average settlement amount received by plainti s also di ers significantly by race. White plainti s, on average, received $12,500. That’s about two and a half times larger than the average received by Black plainti s ($5,000) and more than four times the average received by Latino plainti s ($3,000).

Within each settlement and court case lies a range of untreated medical problems— unexplained aches and pains, overlooked chronic illnesses, and injuries from fights left unmended. Across many of these complaints stands the accusation that incarcerated people were forced to wait months and even years before getting the care they both needed and to which they claim they were legally entitled. Many describe in court filings how the company’s doctors and nurses so seriously ignored their complaints of pain that simply getting through the day became a herculean task, their bodies so riddled with physical and emotional su ering.

One man, who is HIV positive, alleged that he had a tooth infection that dentists at two different prisons failed to treat for so long that the infection spread to his lungs and he fell into a coma. He was hospitalized for two months and nearly died. The company settled his case for $425,000.

In 2008 another man at Stateville complained about pain and swelling in his knee, per his legal complaint. He received a physical exam and an X-ray and was soon transferred to another prison where a nurse said no records existed, so they did another X-ray. Multiple medical practitioners noticed an alarming shadow on the X-ray. Over the next two years, the man underwent a battery of tests but struggled to get information from Wexford doctors about his condition. His pain persisted, and doctors prescribed some medication and gave him crutches. In June 2011, three years after his pain first began, he was diagnosed with stage three cancer from the mass on his knee. He received $15,000 in a settlement.

In 2004, while incarcerated at Illinois River Correctional, Paul went to the health-care unit and said he felt a terrible pain in his right groin. According to his legal complaint, a doctor diagnosed Paul with an inguinal hernia, when soft tissue protrudes through a weak spot in the muscle, but didn’t prescribe treatment. The pain persisted. It impeded Paul’s ability to walk, sleep, and go to the bathroom. Over the next three years, he went back to the health-care unit 16 times. Instead of surgery, the clinicians at the prison shoved the hernia back into Paul’s body, only to have it pop out, over and over again. Every time, Paul said, this hurt tremendously. Wexford eventually settled his claims for $13,000.

Hundreds of stories like these exist both within the documents and within prison walls. In the first few weeks after joining Wexford and other private medical correctional companies, according to attorneys and former employees, doctors and nurses are shown presentations that discuss the di erence between “inmate wants” and “inmate needs.” These presentations, at least in 2008, were followed by an employee handbook that described their soon-to-be patients as “extremely manipulative.” Wexford would not discuss the specific content of their training materials, and said that the company “is focused on making sure that their people are trained so that their patients get the care they need.”

Others don’t see it that way.

“It’s teaching you at the very beginning— before you ever step foot into the prison— these people are going to have a lot of wants, but they’re not going to be needs,” Grady said. “They’re not trying to get better, they’re just trying to manipulate you. And so you have to always be looking at how you’re being manipulated. I’ve deposed so many of their employees. Some of them, I’m left with the feeling that they really don’t intend to harm people, but this is sort of what they’ve been trained to do. And I think there are other people who really have been trained to view people as less than human.” v