3 minute read

Weapons against protesters

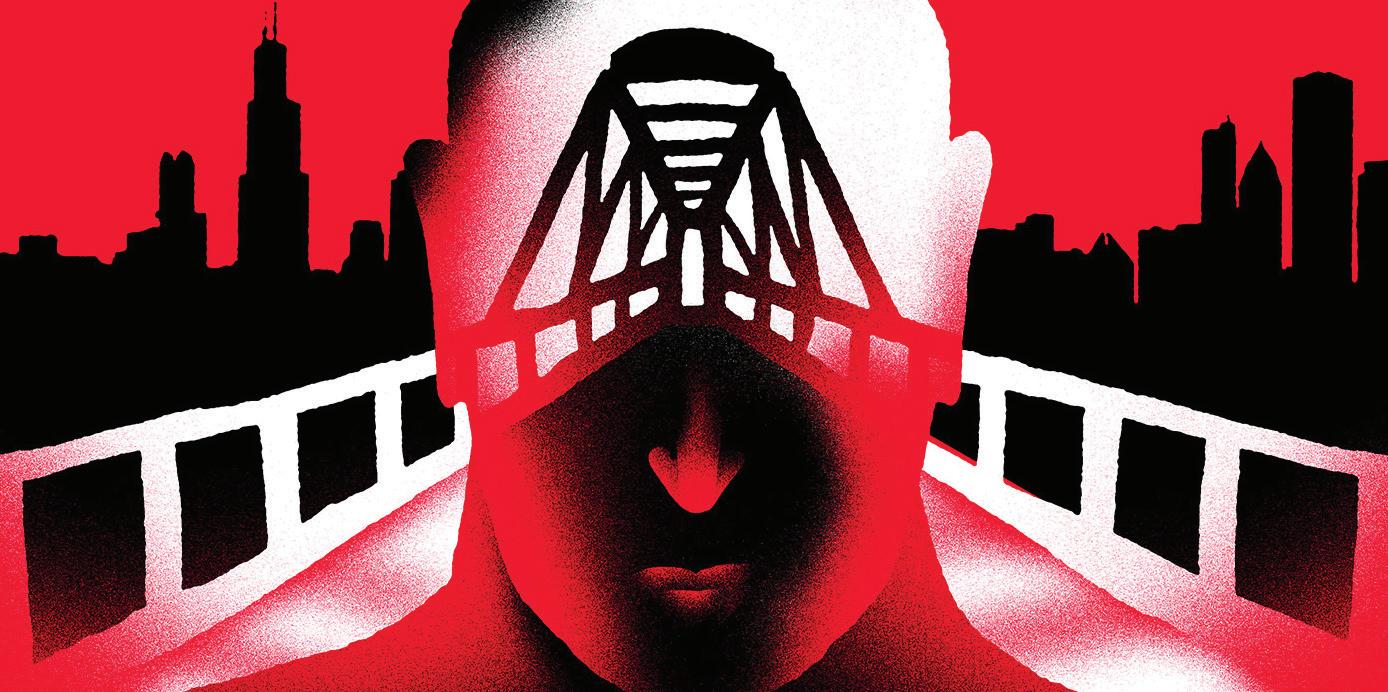

When election and racial justice protests rocked the city, the mayor used raised bridges and shut down public transportation as crowd control measures, which harmed the city’s workers.

By MAYA DUKMASOVA

Minutes before the polls closed on election night in Chicago, massive city sanitation vehicles moved into position outside Trump Tower. Then, the Wabash Avenue bridge— between the president’s namesake building on the north bank of the Chicago River and the Loop central business district on the south— reared up, preventing pedestrians and tra c from crossing.

“Very medieval,” Steven Thrasher, a professor of journalism at Northwestern University, observed on Twitter. Trump Tower, which has been the gathering place for protests since the 2016 election, was suddenly “like a castle protected by the lords pulling up a drawbridge.” Days later bridges were raised again as Chicago residents celebrated

Joe Biden’s projected victory in the presidential election.

Bridges raised above the river bisecting downtown have become a common sight in Chicago since late May, when protests over the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis began. It fi rst happened on May 30, as night fell on the protests amid clouds of tear gas, the drone of helicopters, and the shouts of thousands. People who wanted to make their way out of downtown were confronted with dark walls of concrete, steel, and asphalt reaching skyward, severing movement across some of the city’s main thoroughfares. All but two of the bridges separating the Loop from the Magnificent Mile and other busy commercial neighborhoods to the north were raised.

Typically, the city’s river bridges are only raised to allow high-masted boats to pass in and out of Lake Michigan. But that night, for apparently the first time since

1855, the bridges became weapons in Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s aggressive crowd-control arsenal, which also included strategic public transportation shutdowns and highway exit closures to prevent access to downtown. With scarcely a few minutes’ notice—in the form of cell phone emergency alerts—the city announced a 9 PM curfew while simultaneously making it nearly impossible for people who’d gathered in the Loop to leave.

The pretext for these actions was public safety. “What started out as a peaceful protest has now devolved into criminal conduct,” Lightfoot said at a May 30 press conference an hour before the curfew. “We want to give people ample opportunity to clear the streets. We’re talking about 35 minutes. I think we’re giving them ample notice.” She said the curfew would help o cers “be aggressive in arresting” people engaged in “criminal acts.”

But those who were stranded in the Loop decried Lightfoot’s use of municipal infrastructure, calling it a kettling tactic that makes it easier for police officers to make arrests indiscriminately. Many of the nearly two dozen bridges that span the moat of the Chicago River around the Loop remained raised or closed for days. The city would continue to raise bridges, shut down transit stops, and even discontinue bike-sharing services in the vicinity of smaller protests throughout the summer, and in the wake of protests and looting in Chicago’s most prosperous commercial corridors in early August. Lightfoot’s bridge raising and choking of public transit has become so routine that the satirical news outlet The Onion recently declared Lightfoot was unveiling a plan “to replace Chicago’s public transit system with police.”

As Chicago residents and civic organizations documented the effects of these shutdowns, it became clear that they have had serious ramifications on people’s work commutes, health-care routines, and personal finances. The shutdowns left many feeling that Mayor Lightfoot was more concerned about protecting downtown businesses and some of the city’s wealthiest residents than the police violence that brought people out to the streets. Similar curfews and transit interruptions have become a fact of life in other cities as a wave of demonstrations for racial justice has swept the country.

Robert Alexander, a criminal defense attorney who works in the Loop and lives in South Shore, on the city’s south side, had been commuting to his o ce on the bus despite the COVID-19 pandemic. He often works weekends, so he was in the Loop on that Saturday in May. But when he checked the bus schedule he saw that his usual routes weren’t going farther north than 35th Street, nearly four miles away. The trains weren’t running either. “Then I got the notification that the curfew was happening at 9,” Alexander told The Appeal. “This was 8:58. Then I started freaking out.”

He could hear glass breaking on the street; the windows of Walgreens nearby had been smashed and the sprinklers were blasting inside the shop. When he opened ridesharing