Chicago Studies

Editorial Board

Melanie Barrett Maria Barga Lawrence Hennessey Paul Hilliard John Lodge

Brendan Lupton Kevin Magas David Mowry Anthony Muraya

Patricia Pintado-Murphy Juliana Vazquez Ray Webb

Founding Editor George Dyer

CHICAGO STUDIES is edited by members of the faculty of the University of St. Mary of the Lake/Mundelein Seminary for the continuing theological development of priests, deacons, and lay ecclesial ministers. The journal welcomes articles likely to be of interest to our readers. Views expressed in the articles are those of the respective authors and not necessarily those of the editorial board. All communications regarding articles and editorial policy should be addressed to cseditor@usml.edu. CHICAGO STUDIES is indexed in the ATLA Religion Database and New Testament Abstracts

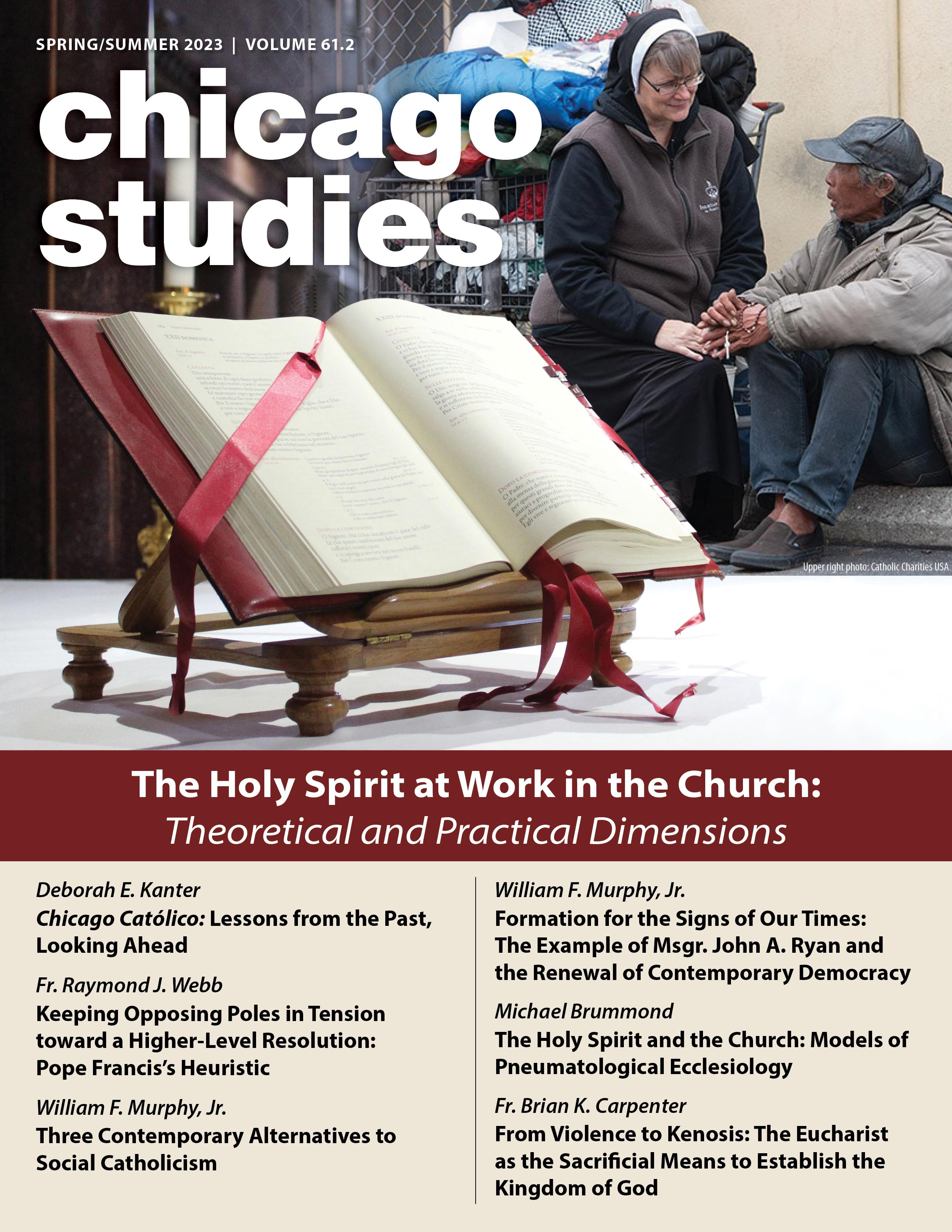

Cover Design by Deacon Thomas Gaida

Copyright © 2024 Civitas Dei Foundation

ISSN 0009-3718

The Holy Spirit at Work in the Church: Theoretical

and Practical Dimensions

Editors’ Corner Volume 61.2, Spring/Summer 2023

By Dr. Juliana Vazquez, Ph.D. and Dr. Melanie Barrett, Ph.D./S.T.D.From social Catholicism, contemporary democracy, and Pope Francis’s heuristic to ecclesiology and the Eucharist, the current volume of Chicago Studies highlights the work of the Holy Spirit in the Church and in the world. At the center of this issue stand highly original contributions from two of USML’s previous Paluch Lecturers, Dr. Deborah E. Kanter and Dr. William F. Murphy, Jr., both of whom explore issues at the intersection of Catholicism and social ethics. The current volume also features a detailed foray into Pope Francis’s theological methodology by Fr. Raymond Webb; a creative contribution to pneumatological ecclesiology by Dr. Michael Brummond; and a thought-provoking article on the Eucharist as the true sacrifice by Fr. Brian Carpenter.

Dr. Murphy’s two consecutive articles examine how the Church’s social tradition can help transform our polarized culture and revitalize contemporary democracy. These contributions can be helpfully contextualized against the backdrop of his larger project of bringing social Catholicism to bear on the most pressing issues of our time. During his time as Paluch Lecturer at USML, Dr. Murphy gave a series of four lectures, all of which mined the Church’s social tradition for a charity-based renewal of society and culture in line with the Gospel message and the dignity of the human person. Murphy contends that such a renewal will issue in an authentic Christian humanism that constitutes the very heart of authentic Catholic social teaching. Insofar as it faithfully receives, discerns, and enacts the magisterial understanding of the Church’s social doctrine, such a humanism provides us with a critical goal and hermeneutic of proper discernment for communal life, political involvement, and institutional reform. In Murphy’s first Paluch Lecture, originally given in October of 2020 and then published as “Liberalism, Conservatism and Social Catholicism for the 21st Century?” in Chicago Studies 60:1 (Fall 2021/Winter 2022), Murphy argues that the authentic social teaching of the Church critiques both the “liberalism” and the “conservatism” currently reigning in the US’s contemporary social and political scene. The Church’s teaching allows us to harness what is good and true in each stance while replacing distortions with a more expansive view of truly human progress. In Murphy’s second Paluch Lecture, originally given in April of 2021 and then published as “St. Paul, St. Thomas Aquinas, and Social Catholicism as Agent of Societal Reconciliation?” in the same past issue of Chicago Studies (Vol. 60:1), he discusses the theological roots of this humanism

Murphy’s third Paluch Lecture was originally given in October of 2021 and at that time was titled “Three Rival Versions of Social Ethics: Contemporary Alternatives to Social Catholicism.” It is published here under the title of “Three Contemporary Alternatives to Social Catholicism” and engages the highly challenging question of why the Chruch’s social teaching often seems to be ignored. Murphy postulates that there are three “rival versions” of social ethics that dominate the intellectual and cultural spaces that sway Catholics and the larger population, threatening to crowd out the more promising answers that social Catholicism provides. In his fourth Paluch Lecture, originally given in April of 2022, Murphy outlines ten theses on how

contemporary Catholics can be intellectually formed to live out a new social Catholicism. In this last Paluch Lecture, published here as “Formation for the Signs of Our Times: The Example of Msgr. John A. Ryan and the Renewal of Contemporary Democracy,” Murphy gives an extensive and appreciative analysis of the life and work of Msgr. John A. Ryan (1869-1945), whom he describes as the most impactful social Catholic in American history and thus an inspiring and instructive model for us. Murphy contends, ultimately, that social Catholicism can aid the renewal of contemporary democracy.

Dr. Deborah Kanter, a native of Chicago and an expert in Latin American history, is the author of Chicago Católico: Making Catholic Parishes Mexican (University of Illinois Press, 2020). The article presented here, “Chicago Católico: Lessons from the Past, Looking Ahead,” was originally given as the 2023 University of St. Mary of the Lake Paluch Lecture. Drawing on her many years of research on Mexican American identity and community formation, Dr. Kanter traces how several generations of Mexican believers contoured the landscape of Catholic communities throughout Chicago with their rich contributions to parish life. She shows how Catholic parishes served as social and spiritual refuges for Mexican immigrants from the 1920s onward. She concludes with some sobering reflections on the situation of immigrants today, underlining the lessons that clergy and lay leaders can glean from history for ministering more effectively to Chicago’s present population of Mexican Catholics.

In his article “Keeping Opposing Poles in Tension toward a Higher-Level Resolution: Pope Francis’s Heuristic,” Fr. Raymond Webb analyzes the Holy Father’s theological methodology. He argues that Pope Francis’s approach to pastoral and ethical discernment is to appreciate the mutual influence of opposite (but not contradictory) poles and to hold them in a fruitful tension. Pope Francis’s heuristic principle critically balances various elements present in a conflict toward a creative, higher-level resolution For example, individual and community, affection and intelligence, universal and particular, spirit and body, unity and difference, are all authentically human aspects of life that must be balanced and put in a constructive dialogue with the other in order for challenging practical conflicts to be resolved and for something new to emerge.

In his article “The Holy Spirit and the Church: Models of Pneumatological Ecclesiology,” Dr. Michael Brummond plumbs the intimate connection between the Spirit and the Church. He creatively applies Dulles’ original five models of the Church for a unique contribution to pneumatological ecclesiology, explicating in detail how each model implies a correspondent pneumatology. Our views on the work of the Spirit in the lives of believers will color how we see the Church; likewise, our ideas on how the Church can and should operate in the world illuminate different aspects of who the Spirit is. In his exploration of this mutual influence, Brummond places Dulles’ contribution in dialogue with a variety of sources, including the CCC, several modern encyclicals, Augustine, Aquinas, and many prominent authors from the liturgical movement.

The volume closes with Fr. Brian Carpenter offering a provocative, cross-disciplinary essay on the Eucharist as the true sacrifice. He proposes that the authentic self-gift of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament is a foil to the false sacrifice described in the mimetic theory of French historian and literary analyst René Girard The false practice of scapegoating innocent victims to escape the tension created by mimetic rivalry is overturned by the true sacrifice of Christ, the Innocent Victim who reveals that such rivalry is both evil and futile. Only the self-gift of Christ on the cross, offered so that all might enjoy true peace with God, overturns such violence and results in the triumph of God’s love in the Resurrection. This one true sacrifice offered by Christ is continued today in the Eucharist, in which God gives Himself in peace and love, allowing us to share in His authentic self-gift for the salvation of others, thus building up the Kingdom of God.

Chicago Católico: Lessons from the Past, Looking Ahead

By Deborah E. Kanter, Ph.D.Let us admit that, for all the progress we have made, we are still ‘illiterate’ when it comes to accompanying, caring for and supporting the most frail and vulnerable members of our developed societies. We have become accustomed to looking the other way, passing by, ignoring situations until they affect us directly.

Pope Francis, Fratelli Tutti

With the parish as my lens into ethnic identity and community formation, I wrote Chicago Católico: Making Catholic Parishes Mexican. Overall, I argue that the Mexicans who settled in Chicago were fortunate to arrive in a multiethnic, Catholic city. My book tells the story of how Mexicans have made a home in Chicago and its churches. Today, Mexicans and other Latinos are transforming the archdiocese into Chicago católico, in ways that past generations of German and Irish bishops, priests, and sisters could not imagine. I use the Catholic parish to view Mexican immigration and transformation in the US For individuals arriving from Mexico, these parishes served as a refugio (refuge). Mexicans fiercely attached themselves to specific parishes, much like European ethnic groups in days gone by. These churches were a place to speak and pray in Spanish, to kneel before a familiar saint, to get job leads, or to reminisce about Mexico. 1

At the same time, these parishes had an Americanizing influence on Mexican members. Men and women took part in regular devotions and parish activities, in ways quite similar to Polish, Italian, or Irish Catholics elsewhere in Chicago. Their children participated in May crownings of the Virgin Mary and played baseball on parish sport teams. Many Mexican American laypeople gained a sense of mexicanidad by participating in its religious and social events. The parish acted as a glue that connected immigrant parents and their US-reared children.

This story of immigrant Catholics and the subsequent generations should be familiar to most readers here, be it of our Polish and Italian grandparents, or of our Korean and Mexican neighbors, school friends, and workmates today. Yet I find that people, especially outside of the Southwest, do not know the depth of the Mexican history in Chicago and the Midwest. 2

Consider the story of an early Mexican Catholic in Chicago. An overalls-clad Matías Lara arrived in Chicago on a chilly November day in 1918 and could not find his way in the city’s hustle and bustle. Lara found himself so lost in Chicago that he entrusted himself to the Virgin of San Juan de los Lagos, “asking that She illuminate the road that I sought.” When the Virgin granted his petition, he then found his way. Lara never shook that feeling of absolute helplessness that

The author thanks Rector/President Fr. John Kartje and Provost Dr. Brian Schmisek for the invitation to deliver the Paluch Lecture at the University of St. Mary of the Lake. Jojo Galvan, Yohan García, Brett Hendrickson, and Julio Rangel provided valuable input. The epigraph is from Fratelli Tutti (Vatican City, 2020), §64, https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20201003_enciclica-fratellitutti.html

1 Deborah E. Kanter, Chicago Católico: Making Catholic Parishes Mexican (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2020). Michael J. Pfeifer takes the parish approach to understand regional history in The Making of American Catholicism: Regional Culture and the Catholic Experience (New York University Press, 2021).

2 Mike Amezcua, Making Mexican Chicago: From Postwar Settlement to the Age of Gentrification (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022); Lilia Fernández, Brown in the Windy City: Mexicans and Puerto Ricans in Postwar Chicago (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012)

enveloped him upon arrival in Chicago and his gratitude for the Virgin’s help. Sometime later, back in Mexico, he painted a retablo (ex-voto), showing himself in overalls, kneeling before the Virgin, candle in hand; behind him, Lara painted the downtown Chicago cityscape as best he could. 3 Crucially, Matías had no Catholic space in which he could express his faith. In 1918, no Catholic churches welcomed the growing numbers of Mexican arrivals. That changed a century ago. In the 1920s, two national parishes were established to welcome the “Spanish speaking ” The Spanish-speaking Claretian Missionaries ministered to Chicago’s growing Mexican population. This congregation arrived in the US in 1902 and tended to Spanish speakers in Texas. When the Claretians heard that 3,000 Mexicans now lived in Chicago, they considered how to reach the mexicanos up north. Fr. Domingo Zaldivar, CMF, wrote to Archbishop Mundelein in 1918 and pointed out the need for Spanish-speaking Catholic ministry in Chicago, a growing destination and settlement for Mexican people. For several years these inquiries went nowhere. The archdiocese acquired a decommissioned wood-frame army barracks to serve as a chapel and moved it to the scrappy South Chicago neighborhood where the steel mills eagerly recruited Mexican men. After some fumbled staffing, Mundelein finally decided to invite a religious order to take on the Mexicans in his archdiocese. In 1924, he chose the Claretians who took over the makeshift chapel known as Our Lady of Guadalupe. So began a century of ministry at Our Lady of Guadalupe that dramatically impacted the growing Mexican colonia. 4

A second Mexican parish soon emerged at a declining German parish in the Near West Side: St. Francis of Assisi. From the 1920s through the 1960s, St. Francis the church, rectory, school, convent, and the gym provided a lively, nurturing home for Mexican immigrants and Mexican American young people. The US-born children may have grown up in poverty, but with a parish to call their own, they did not feel marginalized. The Mexican church anchored the community and its children grew up with a positive grounding in Mexican and US Catholic traditions. Their affirmative experience at St. Francis would manifest itself as thousands of Mexican-origin people entered new neighborhoods in the 1960s. Their movement out of the Near West Side was hastened by expressway construction and forced removal to build the University of Illinois Chicago campus (or “Circle Campus”). In new neighborhoods and in new parishes, dominated by Euro-Americans, many former St. Francis members would assume a vanguard position.

Many people from St. Francis moved to the nearby Pilsen neighborhood. Within this compact geography, Pilsen became home to thirteen parishes between 1874 and 1915. The territorial parish of St. Pius V was established in 1874. Early parishes included the Poles’ St. Adalbert and the Czechs’ St. Procopius; parishes dedicated to serving Slovenians, Germans, Slovaks, Croatians, and Italians followed. The last church erected was the Lithuanians’ Providence of God. Each parish maintained a church, rectory, school, and convent. A lively working-class neighborhood surrounded the thirteen Catholic churches, each with a strong ethnic-linguistic community, as Mexicans and Mexican Americans began to rent flats and buy homes in the midtwentieth century.

3Matías Lara retablo, Mexican Migration Project, accessed August, 9, 2023, https://mmp.opr.princeton.edu/expressions/retablos/ret012-en.aspx

4 The Claretian Missionaries’ arrival in Chicago and growth of Our Lady of Guadalupe are detailed in my forthcoming book, On a Mission: Claretians and the Creation of a National Latino Ministry, 1902-2022 See also Malachy R. McCarthy, “Which Christ Came to Chicago: Catholic and Protestant Programs to Evangelize, Socialize, and Americanize the Mexican Immigrant, 1900-1940” (PhD diss., Loyola University Chicago, 2002)

Pilsen’s Euro-American laity and clergy were not necessarily hostile to the smattering of Mexicans in the pews. Yet the parishes hardly welcomed the new arrivals. In time, Catholicism offered common ground between Euro-American clergy and laity with the newer Spanishspeaking laity. The desire to maintain parish structures explains Euro-Americans’ willingness to live with Mexican newcomers. Priests came to understand that Mexican Catholics could become part of the parish structure. If Mexican people developed loyalties to a fading Czech or Croatian parish, if they enrolled their children at the school, if they dropped a dollar into the weekly collection, an aging parish could keep its doors open. Even so, these new parishioners often opted to attend Mass or Holy Week liturgies at St. Francis of Assisi, a Spanish-speaking church. Chicago Catholic Charities reported in 1955 on the recent arrival of Mexicans in the majority Slavic Pilsen neighborhood. “Mexicans are still viewed as ‘invaders’ by the older residents … However, the Mexican is considered a much lesser evil than the surrounding Negroes.” 5 The specter of “Negro invasion” lay in the shadows of Spanish-speaking integration. Many Pilsen priests expressed a grudging acceptance of Mexican newcomers in the 1950s. By 1965 three Pilsen churches celebrated misa en español.

Pilsen’s pioneering Mexican laypeople shared bittersweet memories of transitional years. The installation of the Virgin of Guadalupe at St. Ann’s took place around 1969 and marked a turning point. A Mexican family at the parish donated the image: “It came from Mexico, with papers and all.” Lupe and Matías Almendarez were selected to carry the image, joining the couple that donated it, through the nearby streets. The two couples proudly carried the Virgin of Guadalupe on a two-block procession, led by a priest, before entering St. Ann’s sanctuary. For decades the image remained prominently displayed by the main altar, parallel to Our Lady of Częstochowa. Taking part in the procession and installation felt “beautiful.” Soon after Mexican parishioners purchased a Mexican flag to place by the Virgin’s side. The installation of the Mexican Virgin marked a change to Mexicans and Poles alike. “The Polish people realized that you weren’t going anywhere.” 6

Consider the story of Julia Rodríguez who arrived from Texas in the 1950s. Once settled in Pilsen and then a new mother, she started attending Mass at nearby St. Procopius. Her initial experience was uncomfortable: “¡Los polacos como que no!” (With the Poles, no way!). 7 While Rodríguez could not pinpoint an inhospitable act at her new parish, she felt unwelcome. She supposed that the older European American parishioners did not like the noise her baby made. Although Julia and her growing family did attend St. Procopius, more often they went to Sunday Mass at St. Francis. She did not know many people there, but she felt more comfortable because the priests and parishioners spoke Spanish.

Fast forward to 1976. Julia, her husband, and several children dressed in folklórico costumes, with a framed print of the Virgin of Guadalupe, stood around a smiling Mayor Richard J. Daley in the mayor’s office. 8 Given her impoverished childhood picking cotton and just a bare-

5 Catholic Charities report, cited in Thomas G. Kelliher, “Hispanic Catholics and the Archdiocese of Chicago, 1923-1970” (PhD diss., University of Notre Dame, 1996), 37. For more on Pilsen’s changing demographics in the 1950s, see Kanter, Chicago Católico, 96-106

6 Quoted from the Almendarez interview in Kanter, Chicago Católico, 118-19.

7 “Polaco” literally means Poles Spanish speakers in Chicago used the label broadly, referring to Czechs, Lithuanians, Poles, and others from Eastern Europe.

8 For photos from that day, see Kanter, Chicago Católico, 138; Richard J. Daley Era Photographs, University of Illinois Chicago, accessed August, 9, 2023, https://collections.carli.illinois.edu/digital/collection/uic_rjdaley/id/2164?fbclid=IwAR33owEAobnya4HSzmq8ixiB ChBdUxoOuI9sYNItwd63cTt47oZsnc1wKYc

bones education, this photo expressed an adulthood of stability, respectability, faith, and belonging. Here Julia stands proudly as a Mexican American Catholic with the pinnacle of her adopted city, the mayor, himself a Catholic. With her husband, Rubén, and the parish children, she represented St. Procopius. Two decades earlier she hesitated to attend Mass there, intimidated by the Euro-American parishioners; in 1976 St. Procopius was home. Chicago had usually been willing to give a chance to Mexicans, fellow Catholics, who, like the Irish, Czechs, Poles, and Lithuanians, also expressed their devotion to the Virgin Mary

Pilsen became Chicago’s first Mexican majority neighborhood precisely in the 1970s. The Mexican Catholic voices grew louder. Just months after Julia visited the mayor’s office, on Good Friday, 1977, the first Via Crucis (Living Way of the Cross) took over Pilsen’s main business artery, 18th Street. These events differed greatly in tone and message, but both showed the rise of a Chicago católico

Seven Pilsen parishes banded together planning, rehearsing, making costumes, growing beards, renting a horse to make a Good Friday that no one would forget. 9 The Via Crucis proclaimed Pilsen as a Mexican and Catholic space in a neighborhood dominated just fifteen years earlier by Poles, Czechs, and Lithuanians. Unprecedented, the 1977 Via Crucis reflected lofty goals of engaging issues of social justice and embodied an identity at once Catholic, Mexican, and Chicano. Julia Rodríguez’s portrait with the Mayor and Pilsen’s Via Crucis both embodied a flourishing Mexican and Catholic identity in 1970s Chicago. These 1970s events were unimaginable a century ago when Matías Lara and other Mexicans first arrived in Chicago. In the 1920s no one would have imagined that Chicago would become the second-largest Mexican metropolis in the US; a metropolis with “a new urban mestizo culture with an identity that spans two nations.” 10 Cardinal Mundelein who gave the green light for two national parishes could not have imagined that the city would be dotted in parishes that serve Spanish-speaking people. In 2023 misa en español is celebrated at eighty-six parishes (or 38 percent of parishes in the Archdiocese of Chicago). 11 The making of Mexican parishes helped generations of immigrants create new homes and identities: first, at St. Francis of Assisi and Our Lady of Guadalupe, then in the past half century at parishes across Pilsen and throughout the city and many suburbs. 12 Since the 1990s new Latin American devotions, for example from Ecuador and Guatemala, have emerged in the parishes. Annual processions wind their way through city streets. The Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Des Plaines, northwest of Chicago, welcomes teeming crowds of the faithful. 13

9 Kanter, Chicago Católico, 123-28. On Chicago’s first Via Crucis, see Robert H. Stark, “Religious Ritual and Class Formation: The Story of Pilsen, St. Vitus Parish, and the 1977 Via Crucis” (PhD diss., University of Chicago, 1981). See also Karen Mary Davalos, “‘The Real Way of Praying’: The Via Crucis, Mexicano Sacred Space, and the Architecture of Domination,” and Roberto S. Goizueta, “The Symbolic World of Mexican American Religion,” in eds. Timothy Matovina and Gary Riebe-Estrella, SVD, Horizons of the Sacred: Mexican Traditions in U.S. Catholicism (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2002)

10 Rita Arias Jirasek and Carlos Tortolero, Mexican Chicago (Chicago: Arcadia, 2001)

11 Current numbers do not include the Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Des Plaines because it is not officially a parish; the Shrine currently celebrates six Spanish Masses. Parish closings have concentrated these Spanish-language liturgies. In 2015 misa en español was celebrated at 130 parishes (or 37 percent of the 351 that comprised the Archdiocese of Chicago).

12 On Chicago’s western suburbs, see David Badillo, Latinos and the New Immigrant Church (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006)

13 Elaine A. Peña, Performing Piety: Making Space Sacred with the Virgin of Guadalupe (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011); Deborah E. Kanter, “‘Thanks to San Juan de los Lagos’: The Evolution of la fé sanjuanera in Chicago,” Dialógo (forthcoming).

I wrote a book about making parishes Mexican, but in these same years we have seen a serious unmaking of parishes in the city. In the past decade church closings have impacted urban core neighborhoods dominated by Latino Catholics, taking away vital places of refuge and social infrastructure. The Pilsen neighborhood supported thirteen parishes ca. 1915 to 1950. Pilsen had seven parishes in 2015; today just three parishes remain.

When St. Ann’s final Mass was announced in 2018, parish leaders worried about what would happen to the saints, including the Virgin of Guadalupe, introduced by the pioneering Mexican families in 1970. For that final Mass the descendants of Polish immigrants, the parish founders, and Mexicans of different generations filled St. Ann’s modest sanctuary on a stifling summer evening. Bishop John Manz delivered the homily in Spanish and English. He acknowledged the feelings of sadness that come with closing a parish, akin to the death of a loved one: “A parish is meant to be a living thing.” Chicago today, the bishop explained, simply had “menos parroquias, menos sacerdotes” (fewer parishes, fewer priests), adding that “the Cardinal is the one who makes the final decision.” He stressed that the church is people, not a building. 14 Yet clearly, the building and its spaces do matter. After the Mass, people, some teary-eyed, recalled sacraments, family events, and repeated prayers carried out in this humble church, in recent times and decades long past.

These current parish closings are inseparable from battles over Mexican identity, gentrification, and feelings of abandonment by the archdiocese. Many Mexican people view the string of parish closings as a symptom of gentrification or the “whitening” of their barrio with its distinctly Mexican Catholic cast since the 1970s. For many Pilsen residents, the notions of home, ethnicity, neighborhood, and faith are intertwined very much as it was for the Irish and Italians a century earlier. In an odd twist of demographic fate, it has fallen to Mexican people to fight to preserve the neighborhood and its structures, including the churches built by Lithuanians, Czechs, and Poles. Latinos are the heirs and conservators of some of the most storied churches in northern cities today, for example, St. Anne’s in Detroit, Our Lady of Mt. Carmel in East Harlem, and St. Stanislaus Kostka in Chicago.

I will close with some brief reflections about the four years since Chicago Católico was published. These have been trying times for Latino people: the hate-inspired mass shooting in El Paso, the pandemic, an unstoppable migration crisis, the xenophobia of the Trump administration and its aftermath, and unresolved hopes for a comprehensive immigration reform. In 2023, as I write, Venezuelan refugees line up for food and housing assistance in Chicago on scorching days; the scene repeats itself in New York, Washington, DC, and elsewhere. For many Latino people, no matter what generation in the US, it can feel like America neither cares about them, nor wants them beyond their role as workers. Further, it sometimes feels like the US Catholic Church neither cares about them nor recognizes their particular trials. Not all pastors appreciate their unique flavors of devotion. Not all pastors understand the ways católicos want to connect with the church and parish. As a result, lay people fear erasure of their culture. Latino Catholics, unbidden, have shared with me the sting of pastors who refuse to celebrate December 12, to honor the Virgin of Guadalupe, in parishes with climbing numbers of Mexican laity. Lisa, a college-educated, second-

14 Author’s notes from final Mass on June 30, 2018. On parish consolidations, see Susan Bigelow Reynolds, “‘This is Not Nostalgia:’ Contesting the Politics of Sentimentality in Boston’s 2004 Parish Closure Protests,” U.S. Catholic Historian 41, no. 1 (Winter 2023); Thomas Rzeznik, “The Church in the Changing City: Parochial Restructuring in the Archdiocese of Philadelphia in Historical Perspective,” U.S. Catholic Historian 27, no. 4 (Fall 2009); John C. Seitz, No Closure: Catholic Practice and Boston’s Parish Shutdowns (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011).

generation Chicagoan, feels hurt when her young pastor quips to Mexican American parishioners after the Mass, “I know two Spanish words: Hallelujah and Amen.” Her nearby parish simply does not feel like home. With exasperation, she told me, “Everyone likes our food, but they should know about our culture.”

As Pope Francis urges, “Let us admit that, for all the progress we have made, we are still ‘illiterate’ when it comes to accompanying, caring for and supporting the most frail and vulnerable members of our developed societies. We have become accustomed to looking the other way, passing by, ignoring situations until they affect us directly.” 15 Given the preponderance of Latino laypeople in the Archdiocese of Chicago, now for decades, many members of the clergy remain “illiterate” in accompanying and recognizing their stories and needs. Clergy and lay leaders can learn from local history and experiments in Latino ministry in generations past. Consider, for example, the Archdiocese’s uneven, piecemeal attempts at Spanish language training. 16 As critically-acclaimed author Alejandra Oliva puts it, “Language helps you identify with your people in a new place, it fills your ears with familiar warmth.” 17 Language is one piece of the puzzle of creating places that welcome and support new Chicagoans. More generally, clergy and laity need to listen, break bread, process in the streets, volunteer at a parish festival, and share pews with Latino Catholics of different generations. Listen, accompany, and support in ways that are meaningful and ongoing.

Newly arrived people face a precarity far from my friend Lisa’s concerns as a secondgeneration Chicago Catholic. Educator Yohan García shares,

Many foreign nationals migrate, under conditions of maximal vulnerability, to seek asylum and protection from harm. In the United States, many of them live invisibly, without any sense of belonging or security. Therefore, it is necessary for migrants and refugees to feel connected and welcomed and for the community of believers to encounter them so that they experience a sense of healing, transformation, and communion. 18

The challenge before us is how to connect and welcome all Mexicans and Venezuelans, Haitians and Africans—in the Chicago católico of today and the future. 19

15 Fratelli Tutti (Vatican City, 2020), §2, accessed August, 9, 2023, https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20201003_enciclica-fratellitutti.html

16 Michael P. Cahill, Catholic Watershed: The Chicago Ordination Class of 1969 and How They Helped Change the Church (Chicago: In Extenso Press, 2014). On the Cardinal’s Committee on the Spanish-Speaking c195570, see Lilia Fernández, “Chicago’s Catholic Archdiocese and the Challenges of Serving a Multiethnic Latino Population,” in eds. Felipe Hinojosa, Maggie Elmore, and Sergio Gonzalez, Faith & Power: Latino Religious Politics Since 1945 (New York: New York University Press, 2022).

17 Alejandra Oliva, Rivermouth: A Chronicle of Language, Faith and Migration (New York: Astra House, 2023), 8.

18 Yohan García, “‘This Is My Body’: A Reflection on My Migrant Journey and the Eucharist,” National Eucharistic Revival, accessed August, 9, 2023, https://www.eucharisticrevival.org/post/this-is-my-body-a-reflectionon-my-migrant-journey-and-the-eucharist?fbclid=IwAR3R1owYJF0JZrsy6

19 Commendable recent books include Susan Bigelow Reynolds, People Get Ready: Ritual, Solidarity, and Lived Ecclesiology in Catholic Roxbury (New York: Fordham University Press, 2023); Brett Hendrickson, Mexican American Religions: An Introduction (New York: Routledge, 2021); Angel Garcia, The Kingdom Began in Puerto Rico: Neil Connolly’s Priesthood in the South Bronx (New York: Fordham University Press, 2020).

Keeping Opposing Poles in Tension toward a Higher-Level Resolution: Pope Francis’s Heuristic

By Reverend Raymond J. Webb, S.T.L., Ph.D.Introduction & Influences

Pope Francis (Jorge Mario Bergoglio) has developed a heuristic principle for conflicted situations of holding opposite poles in tension toward achieving a resolution on a higher plane. This heuristic, seen throughout Francis’s work, can be useful to the practical theologian in seeking solutions to crisis situations of varying scope and intensity: global, situational, discipline-wide, ecclesial, and personal I will begin by providing some background about influences on Pope Francis, principally but not exclusively Gaston Fessard and Romano Guardini. Then I will consider Francis’s heuristic and move to examples of it in practice. Finally, I will consider one situation of interdisciplinary tension, and a second regarding the good of persons two situations in which the principle can be useful to the practical theologian.

Francis (Jorge Mario Bergoglio) certainly has been influenced by South American thinkers. Among them, the Uruguayan Alberto Methol Ferré foresaw the development of the Latin American Church as a “source church” like Europe. Juan Carlos Scannone contributed to the development of the Theology of the People, a Latin American paradigm which is concerned for the poor but does not rely on Marxist categories or argumentation. 1 Bergoglio’s own contribution to Latin American theological thinking can be noted in his role in authoring the Aparecida Document, which was the result of the meeting of Latin American bishops in Aparecida, Brazil in 2007, as well as in his appreciation of the work of the prior 1979 Latin American Episcopal Conference (CELAM) meeting at Puebla, Mexico.

Very important in Bergoglio’s thinking and development have been two European members of the Society of Jesus, the Roman Catholic religious community in which Bergoglio, now Pope Francis, has spent most of his life Gaston Fessard of France and the Romano Guardini of Germany. Fessard’s work on dialectics in the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius was an initial influence on Bergoglio. As Massimo Borghesi notes, 2 Fessard offers a “Christian” notion of dialectics, influenced by Ignatius Christ is the unity of slaves and free people, men and women, Jews and pagans. “Unlike Hegel and Marx, who saw history as the unfolding of largely abstract forces, [Fessard finds that] Ignatius saw it as a function of the playing out of two liberties, God’s free offer of grace and our equally free acceptance or rejection of that offer.” 3 From Fessard’s dialectical understanding of the spiritual exercises, Bergoglio developed the notion about a “polar” Christian life, which Borghesi (2019, 99) sees importantly as his “guiding interpretive criterion.” 4

1 Christine A. Gustafson, “The Pope and Latin America: Mission from the Periphery,” in Pope Francis as a Global Actor: Where Politics and Theology Meet, edited by Alynna J. Lyon, Christine A. Gustafson, and Paul Christopher Manuel (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 192-95.

2 Massimo Borghesi, “The Polarity Model: The Influences of Gaston Fessard and Romano Guardini on Jorge Mario Bergoglio,” in Discovering Pope Francis, edited by Brian Lee and Thomas Knoebel (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press Academic, 2019), 95.

3 Bishop Robert Barron, “Gaston Fessard and Pope Francis,” in Discovering Pope Francis, edited by Brian Lee and Thomas Knoebel (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press Academic, 2019), 123.

4 Massimo Borghesi, “The Polarity Model: The Influences of Gaston Fessard and Romano Guardini on Jorge Mario Bergoglio,” in Discovering Pope Francis, edited by Brian Lee and Thomas Knoebel (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press Academic, 2019), 99.

In 1976 Bergoglio wrote: “The Ignatian vision is the possibility of harmonizing opposites, of inviting to a common table those concepts that seemed irreconcilable, because it brings them to a higher place where they can find their synthesis.” 5 (Bergoglio 1976, 246).

Mid-twentieth-century theologian and philosopher Romano Guardini worked comfortably in the ambit of phenomenology, looking into things themselves and making them known as they wanted to be made known. 6 His ontology was concerned with “living-concrete persons.” A person is a complex unity, with tensions or polarities, like being an individual and also a member of a family. There can be opposites (tensions) but not contradictions in the polarities of the individual. Contradictions exclude each other. Opposites define each other different facets of a united experience. 7 Epistemologically we are knowing subjects who can know reality. Borghesi thinks that Guardini himself may have been motivated to construct this thought-frame because of the crises which were present after World War I 8

Guardini’s work in ontology and epistemology is principally elaborated in his 1925 book, Der Gegensatz, translated into Italian and into Spanish as El Contraste 9 but never into English. Borghesi summarizes Guardini’s opposites into three types:

1. categorical opposites, which are intra-empirical (act-structure, fulness-form, and individuality-totality);

2. trans-empirical, including production-provision, originality-rule, and immanence-transcendence; and

3. transcendental opposites, consisting of similarity-difference and unitymultiplicity. 10

After many years of leadership in the Society of Jesus, Bergoglio went to Germany for doctoral studies, focusing on Guardini. Though his doctoral thesis was never completed (planned for after his retirement as Archbishop of Buenos Aires), Der Gegensatz (“On Opposites” or “On Tensions”) provided the basis for a set of earlier Bergoglio principles regarding polarity. 11 Bergoglio believes these earlier principles promote the common good and social peace. There are four: “reality is superior to ideas,” “time is superior to space,” “unity is superior to conflict,” and “the whole is superior to the parts.” 12 Barrett Turner sees them as developing from the efforts to

5 See Jorge Mario Bergoglio’s 1976 “Fede e giustizia nell’apostolato dei Gesuiti,” in Pope Francis, Pastorale sociale (Milano: Jaca Books, 2015), 246. See the Italian translation of the passage by A. Taroni in M. Borghesi, “The Polarity Model: The Influences of Gaston Fessard and Romano Guardini on Jorge Mario Bergoglio” in Discovering Pope Francis, edited by Brian Lee and Thomas Knoebel (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press Academic, 2019).

6 Robert Athony Krieg, Romano Guardini: A Precursor of Vatican II (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1997), 14.

7 Philip McCosker, “From the Joy of the Gospel to the Joy of Christ,” Ecclesiology 12, no. 1 (2016): 34-36, 46.

8 Massimo Borghesi, The Mind of Pope Francis: Jorge Mario Bergoglio’s Intellectual Journey, tr. Barry Hudock (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press Academic, 2018), 107.

9 Romano Guardini, El Contraste: Ensayo de una filosofia de lo viviente-contrato, intro and trad. A.l.Quintas (Madrid: Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos, 1996).

10 Massimo Borghesi, The Mind of Pope Francis: Jorge Mario Bergoglio’s Intellectual Journey, tr. Barry Hudock (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press Academic, 2018), 108.

11 See Romano Guardini’s 1925 Der Gegensatz (Mainz: Matthias Grünewald, 2019).

12 Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium: The Joy of the Gospel (Vatican: Libreria Editrice Vaticana/Erlanger, KY: Dynamic Catholic Institute, 2013), nos. 231-237.

“achieve a praxis” of the common good in the midst of Latin American challenges and struggles. 13 They are congruent with four basic principles of Catholic social teaching 14 the dignity of the human person, the common good, subsidiarity, and solidarity and they denote a shift not in content but in mode, from proclamation to praxis. Ethna Regan finds that the four principles have been “constant” throughout Francis/Bergoglio’s ministerial life. 15 However, Joseph Flipper claims that the Bergoglio four principles are not entirely the same as Catholic social teaching’s four basic principles, which are directed toward preserving institutions (individual, family, mediating institutions, local government, national government), whereas those of Francis are about changing institutions. 16

Francis’s Heuristic

As mentioned, Francis has long been drawn to a dialectical way of thinking. He finds opposition helpful. Reality is made up of oppositions which do their part to define each other. He thinks of human life as being structured in oppositional form. The desired result of the tension resulting from poles in opposition is the higher-level resolution. He is well aware that life can be an agonizing struggle to overcome conflicts. What I call Francis’s heuristic principle is: polar opposites should be held together in tension with the aim of moving to a higher-level resolution, a “superior solution.” Oppositions are contrary poles (e.g., grace and free will) but not contradictory ones (e.g., good and evil). In no case is a good versus evil opposition or a palpably unjust tension an appropriate pole in the seeking of a higher-level resolution. The goal is a higher-level of solution. It is not “choosing the winner” or “developing options for mutual gain.” It is an achievable, real-world goal. The movement to a higher plane is not usually a compromise or a synthesis except in extremely difficult situations. Whether or not the poles are “equal,” each has something to offer to the higher-level resolution. It is the tension that gives the energy for the higher-level resolutions. Tensions provide energy for newness, previously unthought-of ways of looking at something, searches for alternatives, the discomfort which seeks a solution, the push for a common path, a cooperation which is not a compromise, a “leap” to a new level, an impetus toward solidarity, and a refocusing on the Reign of God “already and not yet” in our midst. Turner observed that we are most fully alive in embracing the polarity in the common projects which are constructed in social life and in the church. “Individuals and the community [are led] through some tension to a hard-won synthesis, without collapsing the tension to one side or the other.” 17 For Francis, following on Guardini’s position, there can be seen in the social polarities a surplus of opposing potentialities that render them capable of being organized into superior levels of social life. There is a new impulse to personal growth entering into community without the loss of individualism, growing into a diversified and life-giving unity, not bogged

13 Barrett Turner, “Pacis Progressio: How Francis’ Four New Principles Develop Catholic Social Teaching into Catholic Social Praxis,” in Journal of Moral Theology, 6, no. 1 (2017): 112

14 Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church, 2004, no. 160.

15 Ethna Regan, “The Bergoglian Principles: Pope Francis’ Dialectical Approach to Political Theology,” Religions 10, no. 12 (December 2019): 670.

16 Joseph Flipper, “The Time of Encounter in the Political Theology of Pope Francis,” in Pope Francis and the Event of Encounter, edited by J. C. Cavadini and D. Wallenfang (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2018), 202 n. 3.

17 Barrett Turner, “Pacis Progressio: How Francis Four New Principles Develop Catholic Social Teaching into Catholic Social Praxis,” in Journal of Moral Theology, 6, no. 1 (2017): 120.

down in conflict. 18 (Francis 2013, 228; Borghesi 2018, 115). Of course, there will sometimes be a tension between the poles which others have built and the desire to move toward the new. Yet Bergoglio cautioned, “Be suspicious of any speech, thought, assertion, or proposal that presents itself as ‘the only way possible.’ There is always another possibility. Maybe a more difficult one, a more committed one, more resisted by those who are comfortably installed and for whom things are going very well.” 19 Bergoglio reminds us that “there is no future without a present or a past: creativity also means memory and discernment, equanimity and justice, prudence and strength.” 20

Polar opposites can include points of view, opinions, interests, qualities, differences, and plans of action which are not contradictory. Other examples are the tensions inherent in his original four principles noted above: ideas and reality, whole and part, unity and conflict, and time and space, as well as center and periphery, act and structure, rule and originality, individual and society, local and global. Francis notes that in conflict one might see “contrapositions” as contradictions or even positions locked in a kind of static coexistence, while what is required is new thinking. 21 Francis’s 2020 Let Us Dream: The Path to a Better Future is replete with examples of tensions in opposition, leading to a higher-level resolution. A few “sketches” of the process can be noted. Church doctrines in apparent opposition require close attention to the specifics of the case. 22 From taking sides or ignoring a conflict (closing one’s eyes), one can move to discerning by “digging deeper.” 23 The vision and restlessness of the young can be in polar contrast with the wisdom yet isolation of the old 24 Yet these seemingly opposed groups can be reenvisioned under the umbrella of family. From the poles of truth and context can come resolution through discernment. 25 Excellent work has been done on conundrums, which are described as confusing or difficult problems or questions. 26 By definition, a conundrum is to be coped with, not necessarily solved. An example is F. Cruz’s description of the “tension” between his repeated acceptance and provision of generous and effective leadership in higher education, and his not having published a single-author book. Friends remind him of how leadership interferes with his scholarship. This is a conundrum for him. The solution is not simply to publish a book. It might be that a contribution to knowledge does not require a book but can be a collectivity of transmitted wisdom through example, or “active knowledge.” The conundrum is in the space for research and publication and its place as an academic criterion for “membership excellence.” Framed in Francis’s heuristic of holding opposing poles in tension moving to a higher-level resolution, Cruz’s conundrum seeks a

18 Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium: The Joy of the Gospel (Vatican: Libreria Editrice Vaticana/Erlanger, KY: Dynamic Catholic Institute, 2013), no. 228, and Massimo Borghesi, The Mind of Pope Francis: Jorge Mario Bergoglio’s Intellectual Journey, tr. Barry Hudock (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press Academic, 2018), 115.

19 Jorge Mario Bergoglio, “To Educate is to Choose Life. Message to the Educational Community. April 9, 2003,” in Jorge Mario Bergoglio/Pope Francis, in In Your Eyes I See My Words: Homilies and Speeches from Buenos Aires, Vol. 1:1999-2004, edited with introduction by A. Spadaro, S.J. and forward by Patrick J. Ryan, S.J., and translation by Marina A. Herrera (New York: Fordham University Press, 2019), 181-82.

20 Jorge Mario Bergoglio, “To Educate is to Choose Life. Message to the Educational Community. April 9, 2003,” in Jorge Mario Bergoglio/Pope Francis, in In Your Eyes I See My Words: Homilies and Speeches from Buenos Aires, Vol. 1:1999-2004, edited with introduction by A. Spadaro, S.J. and forward by Patrick J. Ryan, S.J., and translation by Marina A. Herrera (New York: Fordham University Press, 2019), 177-178.

21 Pope Francis, Let Us Dream: The Path to a Better Future, With Austin Ivereigh. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020), 77-79.

22 Pope Francis, Let Us Dream, 88.

23 Pope Francis, Let Us Dream, 80.

24 Pope Francis, Let Us Dream, 58.

25 Pope Francis, Let Us Dream, 55.

26 J.A. Mercer and Miller-McLemore, Conundrums in Practical Theology (Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2016).

higher-level resolution—in this case, the position that consistently performed knowledge is a place of excellence, a content that can be transmitted in forms other than a book. This reframing does not change that a commonly accepted criterion for academic “excellence” is a single-author book. But Francis’s model might point in a direction of pondering an additional way to conceive “lived and person-born knowledge” in addition to the perceived criterion of a single-author book. Certainly, other conundrums may be more difficult or even impossible to resolve using Francis’s heuristic.

Solidarity is the solution to many situations of poles in tension. Francis describes solidarity as thinking and acting in terms of community. 27 He provides action examples of solidarity. Lives have priority over the acquisition of goods by a few. Unjust structures cannot be replaced by generous philanthropic gestures. The denial of social and labor rights and the ignoring of structural causes of poverty and inequality can be transformed through solidarity. Peace and justice can be the higher-level resolution. Christopher Lamb notes the challenges of Francis’s dialectical method:

Written into the DNA of every bishop is the desire to maintain the unity of the church. Pope Francis is no different. Unity is one of the marks and strengths of the Catholic Church. But maintaining solidarity in a balance between unity and the “synodal” path mapped out by Francis inevitably creates tension. In Church matters, synodal advances at local or church-wide level unleash debate and raise hopes about reforms, yet they can leave people disappointed, as the final decisions remain in the hands of the bishop or the Pope. Francis’s way of dealing with disagreements and tensions is to seek consensus wherever possible, and to hold back until it is achieved. 28

Historical Examples

An example of “higher-level” resolution can be found in Bergoglio’s time in Argentina. During the “Dirty War” in Argentina, 29 some Jesuits supported the guerrillas for social change, while other Jesuits backed the government for stability and anti-communism. Bergoglio, as appointed leader of the Jesuits in his region, desired the “higher-level” of Jesuit unity, while maintaining a low political profile and serving the surrounding populace and saving them from violence.

Pope Francis’s way of dealing with certain disagreements and tensions is to use synods to seek a “higher-level” solution, and to hold back until it is achieved. During the Catholic 2019 Amazon Synod, although a large majority of persons from the region voted to ordain married elders as priests and women as deacons, most of the non-Amazon participants said no. The sides argued. Lacking resolution on a higher plane, at the end, Francis restated the tensions without suggesting a solution. He later implemented higher-level solutions of instituting a permanent Lay

27 Pope Francis, “Address of Pope Francis to the Participants in the World Meeting of Popular Movements,” given in Rome at Old Synod Hall on October 28, 2014, https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/speeches/2014/october/documents/papafrancesco_20141028_incontro-mondiale-movimenti-popolari.html

28 Christopher Lamb, “View from Rome,” The Tablet: The International Catholic Weekly 275 (9390), February 20, 2021, 28.

29 Christine A. Gustafson, “The Pope and Latin America: Mission from the Periphery,” in Pope Francis as a Global Actor: Where Politics and Theology Meet, edited by Alynna J. Lyon, Christine A. Gustafson, and Paul Christopher Manuel (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 191-92.

Ministry of Catechist (i.e., giving ecclesial official recognition of these important ministers) and exhorting priests to minister in the demanding Amazonia region.

Whereas Bergoglio asserts his higher-level goal in theory, there are many practical examples of this maxim. Bergoglio notes that tensions which are mentioned in the Puebla Document the divine and the human, spirit and body, communion and institution, person and community, faith and country, intelligence and affection are universal but can be concretized, moved from ideas to reality. 30 For example, in the pilgrimages of Guadalupe (Mexico) and Luján (Argentina) those poles are held in tension and played out in the solidarity of the action of the pilgrimage. It is the mystical journey of a community of believers, a “living nucleus.”

The polar tensions of a greater voice for many in the Church is in tension with the need to be faithful to the tradition handed down from the earliest of times. Many Christians feel that their perspectives are not important in the direction of the Church. Others worry that a “watering down” or intellectual anarchy could result from a wider voice, even splitting the Catholic Church into schism. (One notes the letter expressing great concern from some United States-based bishops and others to the Bishops of Germany that the Germans were leading the Church into error with their process.) 31 Even Pope Francis has cautioned the German hierarchy. Francis’s penchant for listening to the “peripheries” (the margins, all the voices) seems to have led him to call for a worldwide Synod of Bishops, which would attempt to include all voices in being able to present their positions and arguments. The final Rome-based Synod of Bishops in 2023 will make decisions about the use of “synodality,” but there are risks in Francis’s effort at this “higher-level resolution.”

In September 2021, in accord with his own perspective that nations in unity should take in refugees, and in response to Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s contentions that Hungary’s Christian roots must be preserved, not destroyed by Muslim immigration, and that all rights must be left to nation-states, Francis proposed a higher-level resolution:

The cross, planted in the ground, not only invites us to be well-rooted, it also raises and extends its arms towards everyone…The cross urges us to keep our roots firm, but without defensiveness; to draw from the wellsprings, opening ourselves to the thirst of the men and women of our time….My wish is that you be like that: grounded and open, rooted and considerate. 32

The roots of Christianity are a dynamic tradition, “faith seeking understanding.” The higher-level resolution would call for Prime Minister Orban to understand Catholic tradition in Nostra Aetate of Vatican II and a subsequent document, Human Fraternity for World Peace and Living Together, issued by Pope Francis and the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar (Egypt) Ahmad Al-

30 Jorge Mario Bergoglio, “The Joy of Evangelization. Address on the Sunday Homily at the Plenary Assembly of the Pontifical Commission for Latin America, Rome, January 19, 2005,” in Jorge Mario Bergoglio/Pope Francis, In Your Eyes I See My Words: Homilies and Speeches from Buenos Aires, Vol. 2:2005-2008, edited with introduction by A. Spadaro, S.J. and forward by Patrick J. Ryan, S.J., and translation by Marina A. Herrera (New York: Fordham University Press, 2020), 9.

31 Catholic News Service, “German Bishop Responds to Letter Criticizing Synodal Path,” Chicago Catholic, April 24, 2022, 130 (8), 21.

32 Philip Pullella and Gergely Szakacs, “Pope Francis Urges Hungary to be More Open to Hungry Outsiders,” Reuters September 12, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/hungary-pope-meets-pm-orban-his-politicalopposite-2021-09-12/

Tayyeb in a meeting in United Arab Emirates in 2019. 33 This jointly-issued document calls for “dialogue, understanding and the widespread promotion of a culture of tolerance, acceptance of others and of living together peacefully.” Failure to grow in ways for Christians and Muslims to live together risks the proliferation and expansion of smaller crises.

Education

In the school setting, Francis contrasts the pole of affectivity, hospitality, and tenderness with the pole of objective, specific functions; between heart and reason, between the freedom to ask questions and a body of knowledge, between gratuity and efficiency, between freedom and duty. His educational writings stress the educational process, the relationship of teacher and student, more than the content transmitted. For him, the right to the best education possible also means protecting wisdom (“knowledge that is human and humanizing”). This helps one to pursue meaning in life, rather than banalities, consumerism, and immediate gratification. 34 The resolution at a higher-level will be an educational space that is welcoming and oriented toward growth, where personal development is nurtured as “school, knowledge, and life skills” develop. 35 Education is not adjusting children to the accepted norms of society, “gagging them” and taking away their freedom. Bergoglio wants a “selfless relativization of our way of thinking and feeling” so that we can together search for the truth. 36 Bergoglio advocates “the educational encounter,” which has mutuality—two dimensions—for both students and teachers:

I prefer to define the educator as a person of encounter, and this in its two dimensions: the one who extracts something from within, and the other being the person in authority, the one who nurtures and causes growth. He leads toward true nourishment. [For the student in the educational encounter] there are two dimensions or rather two encounters: encounter with the interior self and encounter with the educator-authority that leads one on the path toward inner encounter. I called this educational encounter...But this cannot be reduced to an active-passive equation. The educator also receives from the student, and that capacity to receive perfects and purifies the educator. Hence, the educational encounter requires mutual acceptance.

37

33 Francis and Ahmad Al-Tayyeb, A Document on Human Fraternity for World Peace and Living Together (Vatican: Libreria Editione Vaticana, 2019). https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/travels/2019/outside/documents/papafrancesco_20190204_documento-fratellanza-umana.html. Accessed May 5, 2022.

34 Pope Francis, Christus Vivit: Christ Lives: Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation (Frederick, MD: Word Among Us Press, 2019), no. 223, page 106.

35 Jorge Mario Bergoglio, “To Educate: Blending a ‘Warm’ and an ‘Intellectual’ Task. Message to the Educational Community. March 28, 2001,” in Jorge Mario Bergoglio/Pope Francis, in In Your Eyes I See My Words: Homilies and Speeches from Buenos Aires, Vol. 1:1999-2004, edited with introduction by A. Spadaro, S.J. and forward by Patrick J. Ryan, S.J., and translation by Marina A. Herrera (New York: Fordham University Press, 2019), 78-9.

36 Jorge Mario Bergoglio, “Let Us not Waste the Opportunity Given to Us. Letter to the Educational Community. April 6, 2005” in Jorge Mario Bergoglio/Pope Francis, In Your Eyes I See My Words: Homilies and Speeches from Buenos Aires, Vol. 2:2005-2008, edited with introduction by A. Spadaro, S.J. and forward by Patrick J. Ryan, S.J., and translation by Marina A. Herrera (New York: Fordham University Press, 2020), 41.

37 Jorge Mario Bergoglio, “The One who Nourishes and Brings About Growth: Address at a Seminar for Rectors. February 9, 2006,” in Jorge Mario Bergoglio/Pope Francis, In Your Eyes I See My Words: Homilies and Speeches from Buenos Aires, Vol. 2:2005-2008, edited with introduction by A. Spadaro, S.J. and forward by Patrick J. Ryan, S.J., and translation by Marina A. Herrera (New York: Fordham University Press, 2020), 73-4.

Peripheries

Francis talks often about the margins, the peripheries, migrants, and refugees. His visit to the Italian island of Lampedusa, off the coast of Libya, early in his pontificate (2013) was an icon of what was to come. This island is the penultimate goal of many seeking to reach Europe, the graveyard of many whose boats cannot bring them to safety, clearly a crisis situation. He sees people emigrating from African countries due to war and the lack of work. Francis clearly and consistently asserts that people living at the so-called peripheries and margins, including refugees and migrants, have rights and considerations warranted by justice. With the right of asylum, migration, and safe residence must come access to the basic necessities of life, including education. Education can provide hope and a future for migrant and refugee children, a chance to develop their potential, more than survival. 38 Yet they often do not have the opportunity for quality education. Recently, previously-generous Bangladesh has been closing refugee schools. Access is limited, especially for girls and in regard to secondary education, as Francis said to members of the Jesuit Refugee Service.

Governor Gregg Abbott of the state of Texas (US) has begun an attempt to deny state aid to government schools which educate some children who do not have legal documents as immigrants. 39 Governor Abbott claims such children are an unnecessary drain on the economy of the State of Texas. This is but one of many efforts undertaken by Governor Abbott, and others, to keep immigrants out in response to what is regularly referred to as “an immigration crisis” in the United States Additionally, he has put pressure on truckers through unnecessarily thorough inspections and stationed Texas National Guard soldiers on borders (not their normal work). From a differing point of view, Mayor Regina Romero of Tucson, Arizona (US) has said that there have been similar surges of people at the southern border before. With some help from the federal government, Tucson’s network of government and nonprofits has worked together to help asylumseekers on the border by providing decent housing, not shelter situations. She wants to uphold the US’s legal obligation and moral duty as Ukraine’s neighbors are doing. Romero viewed Title 42 (which bars immigrants for health reasons) as a political strategy which trivialized the right to seek asylum and ignored the labor shortage afflicting the US. 40

The polar tension may be between the perception that migrants and refugees are a longterm drain on the resources of a country and data from countries showing their contribution to the good of the country over time. Interestingly, the higher-level resolution may be the publicizing of accurate information. The higher-level solution is found in truth about the situation of US immigrants: the currently more than eleven million unfilled job opportunities in the US, the monies migrants pay in taxes and social security, the benefit to the economy of education, and the willingness to foster private and government cooperation. 41

38 Pope Francis, “A Tragic Exodus: Address to Members of the Jesuit Refugee Service. November 14, 2015,” in A Stranger and You Welcomed Me: A Call to Mercy and Solidarity with Migrants and Refugees, ed. Robert Ellsberg (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2018), 36-7.

39 J. D. Goodman, “Abbott Takes Aim at Schooling of Undocumented Immigrants,” New York Times, May 6, 2022, A1, A21.

40 A. Martínez, “How One Arizona City is Preparing for a Potential Influx of Migrants,” National Public Radio, April 5, 2022, https://www.npr.org/2022/04/05/1090992313/how-one-arizona-city-is-preparing-for-apotential-influx-of-migrants. Accessed May 8, 2022.

41 This is a summary of a statistic from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics in 2022, accessed May 15, 2022. For a more current summary of job openings and labor turnover, see https://www.bls.gov/news.release/jolts.nr0.htm

Practical Theology

Practical theology can be described as an intersection between real life concrete situations and theological perspectives coming from both revelation and reason, in light of cultural and social factors. But we can look more deeply at how some of these can be considered as poles in tension looking for a higher-level solution. The discernment of the influence of the poles and reaching a higher-level solution is complex. Some of the complexity will come from how much depth each of the poles is able to bring toward the search for the higher-level resolution, which is also an example of practical theology. We can consider a particular example from the relationship between theology and psychology as well as another about personnel matters and appreciation of the practical demands of human dignity.

To the question of human freedom, theology introduces the concepts of grace and free will, whereas psychology brings dimensions such as structural violence and the question of the influence of the context surrounding individual situations. The issue of how circumstances limit freedom is a contribution to theology, while the heroic virtue God’s grace can bring to seemingly impossible circumstances provides a useful broadening of perspective to both poles and new eyes on human settings.

Every aspect of how the Scriptures describe God’s accompaniment of God’s people can be expressed in psychological terms, which can be modified from discipline-specific words into “common speech,” human terms descriptive of the lives of congregants. Believers can benefit from hearing psychological wisdom in terms they can understand, without the specter of “atheism” overhead. Persons more comfortable with psychological language can be exposed to the humanity found in the biblical narrative and “canon” as well as new slants on accompaniment and ultimates.

Psychology is similarly limited by the point of view of the scientist, presuppositions, interfering “noise,” or unprovided-for variables in its gathering of evidence for the plausibility of hypotheses. Psychology suggests to theology that these intervening variables may be taken into consideration as Bible texts are read or church dogmatic pronouncements are reconsidered. We must suppose that the human sciences can provide evidence-based provisional conclusions about human functioning. We must suppose that psychology cannot have the last word on ultimates. Faith is based on “hints,” not on empirical evidence.

Theology can help psychology with its fundamental premise that there is more than meets the eye, that the unexplainable exists. We may meet in neuroscience, dream analysis, the rediscovery of the unexplainable, even linguistic analysis. We have examples in the mutual understandings of justification between Lutherans and Roman Catholics, and between the Assyrian Church of the East and the Roman Catholic Church on the “communication of idioms” and “theotokos,” the legitimacy of calling Mary the Mother of God. Analysis of language and of meaning represents a recent step toward alleviating centuries of rupture, bringing tensions to higher-level resolutions. Both long-overdue understandings are higher-level resolutions of tragically divisive crises which split the Church. Another higher-level resolution is the difficultto-accept notion that theology and psychology are better and richer and more complete and less prone to error when they are in serious conversation.

Considering a different kind of situation, not infrequently, a certain conflation of theology and psychology takes place in the realm of those who work for or volunteer for the Church. Somehow the work or volunteer situation is thought to be different from similar but non-churchrelated situations. “Working for the Church is a privilege, the ideal situation,” some think when

beginning. With this assumption come expectations. Flaws may be forgiven. One has been loyal, so one cannot be terminated although performance reviews do not meet minimum standards. The “perfect” job can be less than what it had seemed. Long-time Church employees (or volunteers) have rendered great generous service but can see (or not see) a diminishment of their skills and ability to do the required work. They want to be useful, appreciated, even esteemed. Problems can mount with age or physical or mental challenges. Putting age limits in place to solve a particular problem can rob a congregation of much-needed help as the limit impinges on others who retain effective skill levels. Simply ending service can be deflating. Yet the work needs to be done, perhaps even creatively improved. The issue can be addressed a priori when the distinction between organizational psychological issues and theological issues is made clear. Clarity can be dream-deflating but realism is important as one begins the work or task. Lacking that, an a posteriori higher-level resolution may be arrived at Reviewing access compliance issues may solve the problem for the worker, and even the congregation. A higher-level resolution may be putting the employee or volunteer in a new and valued position, fitted to the person’s current ability set and circumstances. A name on a plaque of honor with suitable ceremony, moving from sacristan to greeter in a prominent position, reader of Scripture if appropriate, or titular head of a prayer support group may be higher-level resolutions. Creativity and experience can identify and clarify tensions and look to higher-level resolutions which are creative, more just, more efficient, and hopefully more wisdom-based and graced. What may have seemed to be a crisis to worker or supervisor may simply become a situation calling for a creative higher-level resolution.

Conclusion

Situations of polar opposition will vary in intensity and importance Whether a situation is a polar opposition and also a crisis will depend on the particulars: the perspective of the observer or participant, its scope, and its breadth of effect. Tensions in regard to education and to the plight of migrants are crises and could benefit from use of Francis’s heuristic. The intracongregational tensions could also benefit from Francis’s heuristic, but the term “crisis” might be applied to them only by some. While in particularly taxing situations, higher-level solutions might be compromises or amalgams of elements of both poles, ideally the higher-level resolution must have a newness which is a creative advance. Movement toward a higher-level resolution may come from taking a new perspective, from introducing new elements, from a motivation to refocus on the common good and/or solidarity, or from the paradox of the polar tension producing synergy, in effect new energy. It can develop from the imaginative use, for example, of “brainstorming,” motivated by throwing off presumed restraints for the sake of a higher-level resolution. Sometimes an examination of one’s “absolutes” is needed. Higher-level solutions recently effected by Pope Francis include: creating the Ministry of Catechist, increasingly emphasizing synodality in Church guidance and governance, strongly reiterating everyone’s need of a family, further diversifying church governance (the College of Cardinals), perhaps reducing neoliberal leanings in Church practices, visiting “risky countries,” and inspiring hope rooted in Francis’s vision and creativity in the context of Church tradition.

Three Contemporary Alternatives to Social Catholicism

By William F. Murphy, Jr., S.T.D.Introduction

This article discusses what can be understood as three contemporary alternatives to the renewal of “social Catholicism” that my series of Paluch Lectures explores and for which it advocates.1 As I have presented it in my two previous Paluch Lectures, this social Catholicism can be understood as a nonideological and nonpartisan mode of social and political engagement by Catholics which, guided by the principles and methodology of Catholic social doctrine, addresses the primary challenges of a given time. Although this language of “social Catholicism” is not common in the United States, it is known to those familiar with the history of Catholic social teaching and refers to what I would argue is among the best sources of hope and healing for a world facing grave threats of a dystopian future. Lest one object that the need for a new social Catholicism does not sound like the main social message American Catholics have heard in recent decades, let me note that it aligns perfectly with the “integral and solidary humanism” of the programmatic introductory section to the 2004 Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church (nos. 1-18). This excellent but underappreciated volume was published during the Pontificate of St. John Paul II, and this heading of “integral and solidary humanism” nicely captures the spirit of the Catholic tradition of social teaching as adroitly synthesized by the Compendium. It, therefore, reflects the whole preceding tradition as it has developed under the guidance of the magisterium, especially since the era of the Second Vatican Council, which reflects the alignment of the Church with a postwar humanism that includes support for constitutional democratic states and human rights. This heading of “integral and solidary humanism” also aligns nicely with Pope Francis’s emphases on social friendship, social charity, fraternity, and solidarity. According to the Compendium, this principle-guided, “integral and solidary humanism” can also be understood as the Catholic way to live out Christian charity in the modern world and, arguably, as the authentically Catholic way to evangelize.

In this third of my four Paluch Lectures, I will discuss a significant reason why, especially in the United States, there has been little audience for a social Catholicism along the lines called for by Pope Francis and grounded in the key documents of the tradition, whether the social encyclicals, the conciliar documents, or the Compendium. The reason is that alternative perspectives associated especially with the conservative movement in the United States dominate the intellectual and cultural venues that influence Catholics and the broader population.2

1 An earlier version of this paper was delivered as my third Paluch Lecture on October 27, 2021, at the University of St. Mary of the Lake/Mundelein Seminary, under the title of “Three Rival Versions of Social Ethics: Contemporary Alternatives to Social Catholicism.” For a more comprehensive effort toward a recovery of social Catholicism, see my forthcoming Social Catholicism for the 21st Century? Volume 1: Historical Perspectives and Constitutional Democracy in Peril, edited with an introduction and contributions by William F. Murphy, Jr. (Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2024), and Social Catholicism for the 21st Century? Volume 2: New Hope for Ecclesial and Societal Renewal, edited with an introduction by William F. Murphy, Jr. (Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2024).

2 To a large extent, these alternative “conservative” and often libertarian perspectives have come to dominate the social and political discussion, even among Catholics, despite the warnings of CST against ideologies. A primary explanation for why this has happened can be found in an immense stream of funding and propaganda rebranded “public relations” provided by well-organized networks of business interests promoting a libertarian social vision. These funds are targeted to achieve the goal of shrinking or eliminating the public institutions that might tax or regulate these businesses. Such investments in the political process not only maximize the short-term profits of

In what follows, therefore, I will discuss three of the most prominent contemporary alternatives to this social Catholicism, with the latter being understood as an authentic living out of the social doctrine of the magisterium.3

The first of these is a new articulation of the most visible social orientation of American Catholics in recent decades, which centers on combating elective abortion and other “intrinsically evil” acts.4 This first alternative to social Catholicism also includes a self-described “radical critique” of magisterial Catholic social teaching (CST) since Pope St. John XXIII. The second alternative is Rod Dreher’s “Benedict option” that initially focuses on cultivating intense forms of Christian life and then proceeds to forming “Christian dissidents” to withstand an allegedly immanent “soft totalitarianism” of the left. The third is a radical critique of a very broad understanding of “liberalism” from the perspective of a theological metaphysics, an approach that underlies much of contemporary “postliberal”5 thought among Catholics. This third alternative often aligns with what we might call neo-integralism.

these businesses; they also channel wealth upward (due to tax breaks) and devastate the planet (due to deregulation), while enabling these interests to dominate the political process so they can “rig the system” in their favor. This phenomenon has been well-understood for generations by American social Catholics like Msgr. John A. Ryan, well over a century ago. To accomplish these goals, such interests have also funded those willing to emphasize the culture war issues that distract the public from the questions of justice that shape society and the future. Pope Francis understands this dynamic well as one can tell from a careful reading of Fratelli Tutti: On Fraternity and Social Friendship (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2020). His mostly American critics, on the other hand, seem unaware of it.

An early and revealing example of the opposition of American advocates of laissez faire economics to a Catholic social perspective can be seen in the reaction of the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) to the “Program of Social Reconstruction” published by the US Bishops in 1919. NAM condemned it as socialism, whereas it was largely an anticipation of the social reforms that were widely accepted in postwar democracies but have been under constant attack since the 1980s. For a recent discussion of the long development of the propaganda campaign these interests perfected over the decades since the 1920s, see Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, The Big Myth: How Business Taught Us to Loath Government and Love the Free Market (New York: Bloomsbury, 2023). For an earlier discussion of how similar techniques have been employed on other topics, see another contribution by the same authors entitled Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming (New York: Bloomsbury, 2010). These messages have profoundly penetrated American culture, including Catholics, of course, and we are not seriously engaging the social realm if we are not dealing with the situation forthrightly.