comments by richard e. rodda | phillip huscher

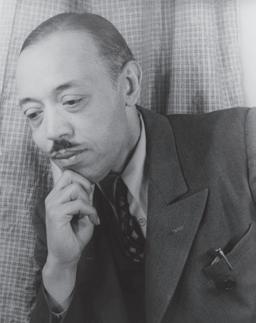

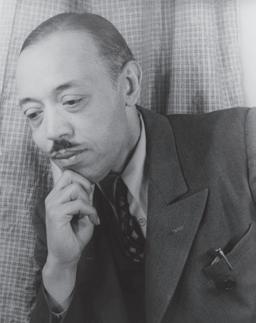

william grant still

Born May 11, 1895; Woodville, Mississippi

Died December 3, 1978; Los Angeles, California

Symphony No. 1 (Afro-American)

William Grant Still, whom Nicolas Slonimsky in his authoritative Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Musicians called “The Dean of Afro-American Composers,” was born in Woodville, Mississippi, on May 11, 1895. His father, the town bandmaster and a music teacher at Alabama A&M, died when the boy was an infant, and the family moved to Little Rock, Arkansas, where his mother, a graduate of Atlanta University, taught high school. In Little Rock, she married an opera buff, and he introduced young William to the great voices of the day on records and encouraged his interest in playing the violin. At sixteen, Still matriculated as a medical student at Wilberforce University in Ohio, but he soon switched to music. He taught himself to play the reed instruments, and left school to perform in dance bands in the Columbus area and work for a brief period as an arranger for the great blues writer W.C. Handy. He returned to Wilberforce, graduated in 1915, married later that year, and resumed playing in dance and theater orchestras.

In 1917, Still entered Oberlin College, but he interrupted his studies the following year to serve in the navy during World War I, first as a mess attendant and later as a violinist in officers’ clubs. He went back to Oberlin after his service duty and stayed there until 1921, when he moved to New York to join the orchestra of the Noble Sissle–Eubie Blake revue Shuffle Along as an oboist. While on tour in Boston with the show, Still studied with George Chadwick, then president of

composed 1930

first performance October 29, 1931; Rochester, New York. Howard Hanson conducting

instrumentation three flutes and piccolo, two oboes, english horn, three clarinets and bass clarinet, two bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, celesta, harp, banjo, strings

above: William Grant Still, photo by Carl Van Vechten

CSO.ORG/INSTITUTE 3

COMMENTS

the New England Conservatory, who was so impressed with his talent that he provided his lessons free of charge. Back in New York, Still studied with Edgard Varèse and ran the Black Swan Recording Company for a period in the mid-1920s. He tried composing in Varèse’s modernistic idiom, but soon abandoned that dissonant style in favor of a more traditional manner.

Still’s work was recognized as early as 1928, when he received the Harmon Award for the most significant contribution to Black culture in America. His Afro-American Symphony of 1930 was premiered by Howard Hanson and the Rochester Philharmonic (the first such work by a Black composer played by a leading American orchestra) and heard thereafter in performances in Europe and South America. Unable to make a living from his concert compositions, however, Still worked as an arranger and orchestrator for radio and Broadway shows, and for Paul Whiteman, Artie Shaw, and other popular bandleaders. A 1934 Guggenheim Fellowship allowed him to cut back on his commercial activities and write his first opera, Blue Steel, which incorporated jazz and spirituals. He continued to compose largescale orchestral, instrumental, and vocal works in his distinctive idiom during the following years, and after moving to Los Angeles in 1934, he supplemented that activity by arranging music for films (including Frank Capra’s 1937 Lost Horizon) and television (Perry Mason, Gunsmoke). Still continued to hold an important place in American music until his death in Los Angeles in 1978.

Still received many awards for his work: seven honorary degrees; commissions from CBS, New York World’s Fair, League of Composers, the Cleveland Orchestra, and other important cultural organizations; the Phi Beta Sigma Award; a citation from ASCAP noting his “extraordinary contributions” to music and his “greatness, both as an artist and as a human being”; and the Freedom Foundation Award. Not only was his music performed by most of the major American orchestras, but he was also the first Black musician to conduct one of those ensembles (Los Angeles Philharmonic, at the Hollywood Bowl in 1936) and a major symphony in a southern state (New Orleans Philharmonic in 1955). In 1945, Leopold Stokowski called William Grant Still “one of our great American composers. He has made a real contribution to music.”

Still’s Afro-American Symphony is one of the landmarks of twentieth-century music, though less as a racial artifact—when Howard Hanson conducted the work’s premiere with the Rochester Philharmonic on October 29, 1931, it became the first symphony by a Black composer played by a major American orchestra—than as a masterful piece of music that speaks eloquently of its creator, its era, and its national roots. The Afro-American Symphony is music that could have been written nowhere but in this country during the Jazz Age by a musician perfectly attuned to America’s voice and spirit. “I knew I wanted to write a symphony,” Still explained.

4 ONE HUNDRED FOURTH SEASON

I knew that it had to be an American work; and I wanted to demonstrate how the blues, so often considered a lowly expression, could be elevated to the highest musical level. . . . Like so many works that are important to their creators, the Afro-American Symphony was forming over a period of years. Themes occurred to me, were duly noted, and an overall form was slowly growing. Long before writing this symphony, I had recognized the value of the blues and had decided to use a theme in the blues idiom as the basis for a major symphonic composition. When I was ready to launch this project, I did not want to use a theme some folk singer had already created, but decided to create my own theme in the blues idiom.

Still’s theme, rooted in the standard twelve-bar blues form, is stated by the muted trumpet after a melancholy introductory soliloquy from the english horn, and recurs, transformed, as a unifying element throughout the symphony. The work follows the standard symphonic plan—large sonata form, adagio, scherzo, uplifting finale—whose moods Still summarized in the movements’ titles: Longing, Sorrow, Humor, and Aspiration. The composer inscribed two further thoughts of his own in the score—“With humble thanks to God, the source of inspiration” and “He who

develops his God-given gifts with view to aiding humanity, manifests truth”— and appended evocative verses by the Ohio-born, African American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872–1906) to each of the four movements:

I. All my life long twell de night has pas’ Let de wo’k come ez it will, So dat I fin’ you, my honey, at last, Somewhaih des ovah de hill.

II. It’s moughty tiahsome laying’ ’roun’ Dis sorrer-laden earfly groun’, An’ oftentimes I thinks, thinks I ’Twould be a sweet t’ing des to die An’ go ’long home.

III. An’ we’ll shout ouah halleluyahs, On dat mighty reck’nin’ day.

IV. Be proud, my Race, in mind and soul.

Thy name is writ on Glory’s scroll

In characters of fire. High mid the clouds of Fame’s bright sky

Thy banner’s blazoned folds now fly, And truth shall lift them higher.

—Richard E. Rodda

CSO.ORG/INSTITUTE 5 COMMENTS

COMMENTS

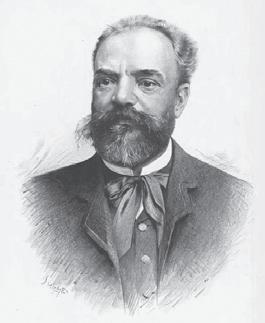

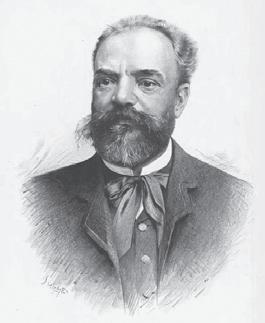

antonín dvořák

Born September 8, 1841; Nelahozeves, Bohemia

Died May 1, 1904; Prague, Bohemia

Symphony No. 8 in G Major, Op. 88

Dvořák was the first of the great European composers to visit Chicago. He came as a star attraction at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, where he conducted the Chicago Symphony—billed as the Exposition Orchestra for the occasion, and then known as the Chicago Orchestra—in this G major symphony. Dvořák’s music was already popular in the city. Theodore Thomas, founder of the Chicago Symphony, had programmed Dvořák’s Husitská Overture to close the Orchestra’s inaugural concert in October 1891, and he led the U.S. premiere of his Violin Concerto just three weeks into the season.

“Dvořák Has Arrived,” ran a headline in the Chicago Daily Tribune on August 12, 1893. “In disposition he is modest and retiring and does not look near as fierce as would be supposed from his picture,” the paper reported. Dvořák, his wife, and their children had already taken up residence at the new Lakota Hotel, on the southeast corner of Michigan Avenue and 30th Street. The centerpiece of Dvořák’s visit was his headliner appearance with the Chicago Symphony in Festival Hall in honor of Bohemian Day, August 12. “The day was cool and bright,” the New York Times reported, “and the visitors evinced the keenest pleasure in viewing the many things of interest.” A crowd estimated at 10,000 watched a morning parade wind through the city’s South Side streets. Swarms of Bohemians, wearing blue and red, the national colors of Bohemia, began to arrive at the fair as soon as the

composed

August 26–November 8, 1889

first performance

February 2, 1890; Prague, Bohemia

instrumentation two flutes with piccolo, two oboes and english horn, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, strings

approximate performance time 36 minutes

6 ONE HUNDRED

SEASON

FOURTH

above: Antonín Dvořák, from Portraits of Czech Personalities, a collection of Czech leaders in a variety of fields, by Jan Vilímek (1860–1938)

parade was over, “and they came in such crowds that the hearts of the exposition officials were filled with joy.” Festival Hall, a great domed, colonnaded amphitheater overlooking a lagoon and situated at the intersection of two broad promenades, was packed for the afternoon concert of Bohemian music. The hall seated 4,000, with standing room for another 2,000. The Exposition Orchestra, as it was billed, was essentially the Chicago Orchestra expanded to 114 men.

“As Dvořák walked out upon the stage, a storm of applause greeted him,” the Chicago Daily Tribune reported “For nearly two minutes the old composer stood beside the music rack, baton in hand, bowing his acknowledgments. The players dropped their instruments to join in the welcome.” Another article remarked that “the importance of the concert naturally centered in the Dvořák Symphony, a work of rare melodious beauty.” The Tribune concluded: “The orchestra caught the spirit and magnetism of the distinguished leader. The audience sat as if spell-bound. Tremendous outbursts of applause were given.”

The G major symphony was listed as no. 4, which is how it was known during the composer’s lifetime, although we now number it the eighth of Dvořák’s nine symphonies. In fact, to the late nineteenth century, Dvořák was the composer of just five symphonies; only with the publication of his first four symphonies in the 1950s did we begin to use the current numbering. Soon, even generations of music lovers who grew

up knowing this genial G major symphony as no. 4 came to accept it as no. 8.

In the 1880s and ’90s, Dvořák was as popular and successful as any living composer, including Brahms, who had helped promote Dvořák’s music early on and had even convinced his own publisher, Simrock, to take on this new composer and to issue his Moravian Duets in 1877. Dvořák proved to be a prudent addition to the catalog, and the Slavonic Dances he wrote the following year at Simrock’s request became one of the firm’s all-time best sellers. Dvořák was then insulted and outraged, when, in 1890, Simrock offered him only a thousand marks for his G major symphony (particularly since the company had paid three thousand marks for the last one), and he gave the rights to the London firm of Novello instead. (At least he did not follow the greedy example set by Beethoven and sell the same score to two different publishers.)

Dvořák’s G major symphony is his most bucolic and idyllic—it is, in effect, his Pastoral—and like Brahms’s Second or Mahler’s Fourth, it stands apart from his other works in the form. Like the subsequent New World Symphony, composed in a tiny town set in the rolling green hills of northeast Iowa, it was written in the seclusion of the countryside. In the summer of 1889, Dvořák retired to his country home at Vysoka, away from the pressures of urban life and far from the demands of performers and publishers. There he realized that he was ready to tackle a new symphony—it had been four years since his last—and that he was eager to compose

CSO.ORG/INSTITUTE 7 COMMENTS

something “different from the other symphonies, with individual thoughts worked out in a new way.”

Composition was remarkably untroubled. “Melodies simply pour out of me,” Dvořák said at the time, and both the unashamedly tuneful nature of this score and the timetable of its progress confirm the composer’s boast. He began his new symphony on August 26; the first movement was finished in two weeks, the second a week later, and the remaining two movements in just a few days apiece. The orchestration took only another six weeks.

The first movement is, as Dvořák predicted, put together in a new way. The opening theme—pointedly in G minor, not the G major promised by the key signature—functions as an introduction, although, significantly, it is in the same tempo as the rest of the movement. It appears, like a signpost, at each the movement’s crucial junctures—here, before the exposition; later, before the start of the development; and finally, to introduce the recapitulation. Dvořák is particularly generous with melodic ideas in this movement. As Leoš Janáček said of this music: “You’ve scarcely got to know one figure before a second one beckons with a friendly nod, so you’re in a state of constant but pleasurable excitement.”

The second movement, an adagio, alternates C major and C minor, somber and gently merry music, as well as passages for strings and winds. It is a masterful example of complexities and contradictions swept together in one

great paragraph. The central climax, with trumpet fanfares over timpani roll, is thrilling.

The third movement is not a conventional scherzo, but a lilting, radiant waltz marked Allegretto grazioso—the same marking Brahms used for the third movements of his second and third symphonies. The main theme of the trio was rescued from Dvořák’s comic opera The Stubborn Lovers, where Tonik worries that his love, Lenka, will be married off to his father.

The finale begins with a trumpet fanfare and continues with a theme and several variations. The theme, introduced by the cellos, is a natural subject of such deceptive simplicity that it cost its normally tuneful composer nine drafts before he was satisfied. The variations, which incorporate everything from a sunny flute solo to a determined march in the minor mode, eventually fade to a gentle farewell before Dvořák adds one last rip-roaring page to ensure the audience enthusiasm that, by 1889, he had grown to expect.

—Phillip Huscher

Richard E. Rodda, a former faculty member at Case Western Reserve University and the Cleveland Institute of Music, provides program notes for many American orchestras, concert series, and festivals.

Phillip Huscher is the program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

8 ONE HUNDRED FOURTH SEASON COMMENTS

Ken-David Masur Conductor

During the 2022–23 season, Masur leads a range of programs with the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra, where his programming explores the natural world and its relationship to humanity. He also continues the second year of an MSO artistic partnership with pianist Aaron Diehl, and leads choral and symphonic works including Mendelssohn’s Elijah and Mahler’s Symphony no. 2. With the Civic Orchestra of Chicago, Masur leads concerts throughout the season. Other engagements include subscription weeks with the Nashville and Omaha symphony orchestras, and a return to Poland’s Wrocław Philharmonic.

Last season, Masur made debuts with the San Francisco Symphony, the Minnesota Orchestra, and the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, and led performances with the Rochester Philharmonic and the Kristiansand Symphony Orchestra.

Masur has conducted distinguished orchestras around the world, including the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Orchestre National de France, the Yomiuri Nippon Symphony, the Orchestre National du Capitole de Toulouse, the National Philharmonic of Russia, and other orchestras throughout the United States, France, Germany, Korea, Japan, and Scandinavia. Previously Masur was associate conductor of the Boston

Symphony Orchestra, where he led numerous concerts, at Symphony Hall and at Tanglewood, of new and standard works featuring guest artists such as Renée Fleming, Dawn Upshaw, Emanuel Ax, Garrick Ohlsson, Joshua Bell, Louis Lortie, Kirill Gerstein, Nikolay Lugansky, and others. For eight years, Masur served as principal guest conductor of the Munich Symphony, and also as associate conductor of the San Diego Symphony and resident conductor of the San Antonio Symphony.

Music education and working with the next generation of young artists are of major importance to Masur. In addition to his work with the Civic Orchestra of Chicago, he has led orchestras and master classes at Tokyo Bunka Kaikan Chamber Orchestra, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee’s Peck School of the Arts, New England Conservatory, Boston University, Boston Conservatory, the Tanglewood Music Center Orchestra, and at other leading universities and conservatories throughout the world.

Masur is passionate about the growth, encouragement, and application of contemporary music. He has conducted and commissioned dozens of new works, many of which have premiered at the Chelsea Music Festival, an annual summer music festival in New York City founded and directed by Masur and his wife, pianist Melinda Lee Masur.

Ken-David Masur holds the Robert Kohl and Clark Pellett Principal Conductor Chair with the Civic Orchestra of Chicago.

CSO.ORG/INSTITUTE 9 profiles

PHOTO BY ADAM DETOUR

2023 Chicago Youth in Music Festival

The Chicago Youth in Music Festival is an annual celebration of young musicians who are passionate about symphony orchestras.

The 2023 Chicago Youth in Music Festival began on March 24 at Symphony Center and has featured students from across Chicago. The Festival is presented in partnership with Chicago Youth Symphony Orchestras, as well as Chicago Arts and Music Project, Chicago Metamorphosis Orchestra Project, The People’s Music School, Sistema Ravinia, Amundsen High School, Kenwood Academy, Mather High School, Northside College Prep, and the Chicago Musical Pathways Initiative.

On Friday, March 24, 100 Chicago Public Schools string orchestra students from four partner schools convened for sectionals and a side-by-side rehearsal with musicians from the Civic Orchestra of Chicago, led by conductor Kyle Dickson. The participating schools were Amundsen High School, Kenwood Academy, Mather High School, and Northside College Prep. A small ensemble of Civic Orchestra Mentors visited each school in advance to lead sectionals on the Festival repertoire.

On Sunday, March 26, seventy-five students from four community music schools gathered for sectionals and

a side-by-side rehearsal and performance with the Civic Orchestra, led by Chicago Youth Symphony Orchestra’s music director, conductor Allen Tinkham. In addition, students and their families attended the Chicago Symphony Orchestra concert that afternoon conducted by Thomas Wilkins.

Today you hear the advanced Festival Orchestra comprised of sixty students representing Chicago Youth Symphony Orchestras and the Chicago Musical Pathways Initiative sitting side by side with musicians from the Civic Orchestra of Chicago. The Festival Orchestra has rehearsed throughout the weekend with conductor Kyle Dickson and participated in sectionals with CSO musicians in preparation for today’s public open rehearsal led by Civic Orchestra Principal Conductor and Music Director of the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra, Ken-David Masur.

partners

Amundsen High School

Chicago Arts and Music Project

Chicago Metamorphosis Orchestra Project

Chicago Musical Pathways Initiative

Chicago Youth Symphony Orchestras

Kenwood Academy

Mather High School

Northside College Prep

The People’s Music School

Sistema Ravinia

CSO.ORG/INSTITUTE 11 PROFILES

Negaunee Music Institute at the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Across Chicago and around the world, the Negaunee Music Institute connects people to the extraordinary musical resources of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Programming educates audiences, trains young musicians, and serves diverse communities, with the goal of transforming lives through active participation in music.

Current Negaunee Music Institute programs include CSO School and Family Concerts; open rehearsals; in-depth school and community partnerships; the Civic Orchestra of Chicago; intensive training and performance opportunities for young musicians including the Percussion Scholarship Program, Chicago Youth in Music Festival, and Crain-Maling Foundation CSO Young Artists Competition; and education and

community engagement activities during CSO domestic and international tours. Worldwide, the Negaunee Music Institute’s annual reach is approximately 200,000 through all channels, including radio broadcasts, teacher’s guides, and online resources.

Founded in 1919, the Civic Orchestra of Chicago is a signature program of the Negaunee Music Institute. Civic Orchestra members participate in rigorous orchestral training led by Principal Conductor Ken-David Masur, musicians of the CSO, and luminary guest conductors, including CSO Zell Music Director Riccardo Muti. The importance of the Civic Orchestra’s role in Greater Chicago is underscored by its commitment to present free concerts at Symphony Center and in neighborhoods throughout the city. Civic Orchestra performances can also be heard locally on WFMT (98.7 FM).

cso.org/institute

12 ONE HUNDRED FOURTH SEASON PROFILES