14 minute read

THE REGIONAL LANDSCAPE FOR GEOTHERMAL DEVELOPMENT

by CHOA

United States

US Geothermal Production Focused on High-Temperature Hydrothermal Resources

Advertisement

The US West region has extremely favourable conditions for the development of geothermal resources (see Figure 29) In the hottest regions, geothermal wells with depths under 1,000 m are capable of producing brine in excess of 1,500 C – providing ample opportunities for commercial power generation.

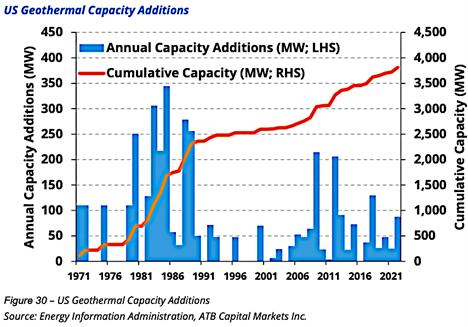

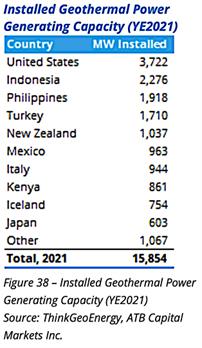

According to ThinkGeoEnergy, the US led all countries in geothermal generation capacity in 2021, at 3,722 MW, or 23% of global installed capacity. Even then, the EIA’s preliminary data indicates that geothermal represented just 0.4% of the country’s utility-scale generation in 2021.

“ … the US led all countries in geothermal generation capacity in 2021, at 3,722 MW, or 23% of global installed capacity.”

According to the DOE’s GeoVision analysis, geothermal power generating capacity could be built up to 60 GW by 2050 assuming a streamlined regulatory and permitting process, aggressive technology advancements, and cost reductions (especially for EGS).

Figure 30 illustrates the pace of US geothermal electrical generation capacity additions since 1971. It shows a steep ramp in geothermal capacity in the 1980s which followed the creation of the Geothermal Steam Act of 1970, the Geothermal Loan Guarantee Program in 1974, and the formation of the Department of Energy in 1977

The 1980s boom in geothermal capacity was largely related to the development of California’s Imperial Valley and Salton Sea field and the demonstration of binary cycle power generation, which further gave rise to developments in Hawaii, Nevada, and other regions. Geothermal capacity growth slowed significantly in the 1990s until the early 2000s – likely given an era of cheap energy as real power prices (inflation-adjusted) declined from the early 1980s through 2000; per EIA data, the average US retail power price, in real terms, peaked in 1985 at roughly $0 21/kWh (in July 2022 dollar terms) and declined steadily to a low of roughly $0.14/kWh in 2002 before stabilizing. A period of renewed growth began at roughly the same time as the introduction of the 2005 Energy Policy Act, which amended the Geothermal Steam Act of 1970 and set new royalty and lease structures and provided production incentives and research funding for geothermal projects.

US Regulatory Regime

Geothermal Resource: The Geothermal Steam Act of 1970 defined geothermal resources as: 1) all products of geothermal processes – indigenous steam, hot water, and hot brines; 2) steam and other gases, hot water, and hot brines resulting in fluids artificially introduced into geothermal formations; 3) heat or other associated energy found in geothermal formations; and 4) any by-product derived from the aforementioned. Any minerals found in solution with the geothermal resource, which are not economic to produce on their own, are considered by-products under the Act

Resource Ownership and Access: Lands subject to geothermal leasing include: 1) public, withdrawn, and acquired lands; 2) national forests or other lands administered by the Department of Agriculture through the Forest Service; and 3) lands that have been conveyed by the US subject to a reservation to the US of the of the geothermal resources therein – in effect, all land managed by the Bureau of Land Management. In 2019, this represented about 40% of the total US geothermal energy generated

The remainder of geothermal capacity is installed on a combination of private land and land that is managed by a state. A developer must agree with the owner of surface rights before development begins, whomever the party Next, if the subsurface rights reside with the landowner, that must also be agreed upon; otherwise, the developer must apply with the appropriate governmental body – federal or state.

Oversight, Licencing and Enforcement: Oversight and licencing is based on the rightsholder. In the exploration/testing stage, a surface owner must give permission if the land is privately owned; otherwise, the respective state or the BLM (for federal land) must grant a lease A developer must also obtain a permit from the state’s water resources administration. When the field undergoes development and moves towards the operational stages, the project proponent must apply with the EPA to obtain a permit for reinjection into a geothermal resource. Additionally, all geothermal projects must have a separate environmental review under the National Environmental Policy Act at the exploratory stage and prior to the utilization of the resource.

Royalties: Royalties are governed by the Geothermal Steam Act of 1970, amended by Sec. 224 of the Energy Policy Act of 2005. During the first 10 years of production, 1.0%-2.5% of gross proceeds from the sale of electricity are due. After that period, this range increases to 2.0%-5.0%. Half of the total royalties collected are paid to the state, 25% to the county, and 25% to the U S Treasury Rents on competitive geothermal leases under the scope of the Geothermal Steam Act of 1970 are calculated at a rate of US$2/acre on the first year of the lease, increasing to US$3/acre for years 2-10 and US$5/acre thereafter. By-products from the production of brine are subject to the Mineral Leasing Act.

The remainder of geothermal capacity is installed on a combination of private land and land that is managed by a state. A developer must agree with the owner of surface rights before development begins, whomever the party Next, if the subsurface rights reside with the landowner, that must also be agreed upon; otherwise, the developer must apply with the appropriate governmental body – federal or state.

Oversight, Licencing and Enforcement: Oversight and licencing is based on the rightsholder. In the exploration/testing stage, a surface owner must give permission if the land is privately owned; otherwise, the respective state or the BLM (for federal land) must grant a lease A developer must also obtain a permit from the state’s water resources administration. When the field undergoes development and moves towards the operational stages, the project proponent must apply with the EPA to obtain a permit for reinjection into a geothermal resource. Additionally, all geothermal projects must have a separate environmental review under the National Environmental Policy Act at the exploratory stage and prior to the utilization of the resource.

Royalties: Royalties are governed by the Geothermal Steam Act of 1970, amended by Sec. 224 of the Energy Policy Act of 2005. During the first 10 years of production, 1.0%-2.5% of gross proceeds from the sale of electricity are due. After that period, this range increases to 2.0%-5.0%. Half of the total royalties collected are paid to the state, 25% to the county, and 25% to the U S Treasury Rents on competitive geothermal leases under the scope of the Geothermal Steam Act of 1970 are calculated at a rate of US$2/acre on the first year of the lease, increasing to US$3/acre for years 2-10 and US$5/acre thereafter. By-products from the production of brine are subject to the Mineral Leasing Act.

ALBERTA, CANADA

While well-mapped and well-supplied with energy services companies and equipment, Alberta’s potential for geothermal is limited given the current state of geothermal technology. The main issue lies with subsurface temperatures –the temperature gradient is not conducive to the production of hot brine from shallower depths. Second, the price of electricity in the province is very low given the availability of fossil fuels.

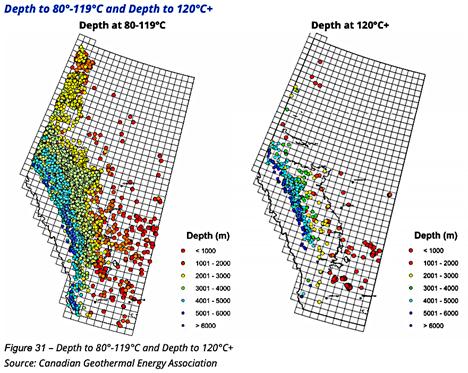

Nonetheless, Alberta could potentially support the use of geothermal for direct use applications, including district heating or in industrial processes, and perhaps low-grade electricity generation. The Canadian Geothermal Energy Association (CanGEA) has published maps that show the depth required to attain certain temperatures (see Figure 31).

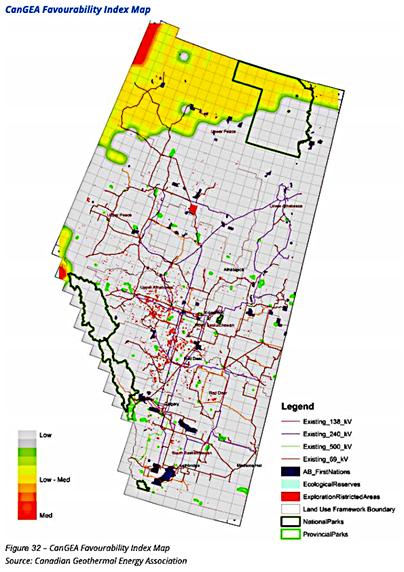

These maps illustrate that there is significant potential for geothermal resource development for ORC binary plants in the western portion of the province, with some clustering around the Greenview/Grande Prairie area – which is the area targeted by Terrapin with its Alberta No.1 project. Eavor also placed its EavorLite demonstration project near Rocky Mountain House in the west. While the east appears attractive based on depth to temperature, these areas are not considered favourable by CanGEA, which we believe is likely due to demonstrated low flow rates. CanGEA’s favourability map shows the areas where development is most likely (see Figure 32).

Alberta Regulatory Regime

In October, 2020, Alberta introduced Bill 36: The Geothermal Resource Development Act (GRDA), which came into force in June 2022 and amended certain items within the existing Mines and Minerals Act. The GRDA established a regulatory framework for geothermal developments in Alberta, including provisions related to defining resources and royalties, resource use and ownership, minimum well design features (casing, blowout prevention, etc.) and abandonment, licensing, liability, and oversight Additionally, the GRDA led to the release of AER Directive 089: Requirements for Geothermal Resource Development, which specifically notes that many of the requirements for geothermal development are the same as for oil and gas development

Geothermal Resource and Royalties: The GRDA defines geothermal resources as natural heat from the Earth that is below the base of groundwater protection. Under the amendment to the Mines and Minerals Act, geothermal royalties are payable to the Crown for reservoirs that are property of the Crown, similar to oil and gas royalties, though we were not able to determine royalty rates at this time.

Resource Ownership and Access: In Alberta, the title to geothermal resources is held through the mineral title as set forth by the Mines and Minerals Act. We understand that roughly 80% of mineral titles in Alberta are held by the Crown, while 20% are held freehold. For freehold titles, some may have parsed mineral rights for different resources, and, as a result, those seeking geothermal development may be required to gain approval from all bearers of mineral rights at a location.

Oversight, Licencing, and Enforcement: Similar to the Oil and Gas Conservation Act (OGCA), the GRDA assigns the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) as the primary oversight authority in charge of exploration and development activities and gives it authority to make rules regarding licensing, environmental, and operational aspects including operating standards, environmental standards, suspensions, abandonments and reclamations, and monitoring and gives it certain enforcement capabilities In addition to the GRDA, geothermal developments may be subject to environmental laws as prescribed under the Water Act and the Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act, though we understand that the Water Act includes an exemption for saline groundwater, which likely covers the majority of geothermal resources.

The One & Only CHOA STAMPEDE FREESTYLIN’ PARTY!

We invite you to enjoy an evening of music, activities, and networking. We organize the party within the party for you and your valued clients

Where: The Hotel Arts – The Freestyle Social Club

When: July 6th, 2023, 3:30 – 6:30 PM, MT

Your ticket includes hot and cold appetizers and access to the cash bar. Drink tickets are available for purchase at the door

Grab your hats and boots and join us on July 6th! REGISTER HERE

SASKATCHEWAN, CANADA

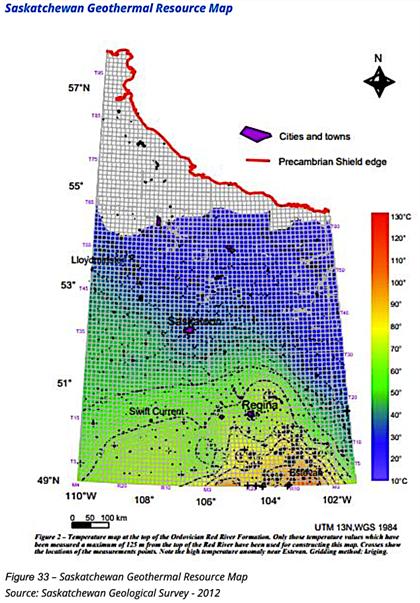

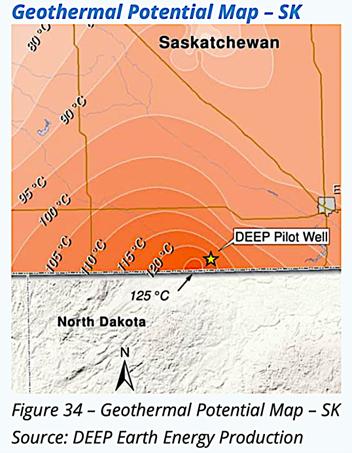

Apart from the south-central region of Saskatchewan, the province has a relatively low-grade geothermal resource. Saskatchewan has no current operational geothermal power generation capacity, though DEEP Earth Energy is pursuing a project to become Canada’s first major geothermal power producer.

Saskatchewan Regulatory Regime

Among the jurisdictions we looked into, Saskatchewan has the least-formallydeveloped regulatory regime as it relates to geothermal development. Within the province, there exists no specific geothermal legislation – instead, wells are regulated by a combination of sources, which we believe at least includes the Mineral Resources Act (MRA), the Oil and Gas Conservation Act (OGCA), and the Water Security Agency Act (WSAA). Despite the clarity in legislation, Saskatchewan empirically is further along the development path than Alberta, which may be the result of a better geothermal resource and/or a supportive government Ultimately, applications for geothermal projects are submitted to the Integrated Resource Information System (IRIS) for the Ministry of Energy and Resources to review.

Geothermal Resource: Under all applicable legislation, there is no reference to geothermal resources or development. However, the MRA considers any opening in the ground that obtains water to inject into an underground formation to be a well. Furthermore, given the potential for lithium brine extraction in certain Saskatchewan-based developments, geothermal wells fall under the purview of both the OGCA and the WSAA.

Resource Ownership and Access: To develop a well, surface rights must be obtained from the pertinent freehold landowner. If brine is being extracted for supplemental revenue streams, mineral rights substantially reside with the Crown and are subject to public offerings. Resource developers must participate in a competitive bid process to obtain these rights. Meanwhile, the right to use all groundwater is vested in the Crown – which adds a water licensing requirement for effectively all geothermal developments that use water as a working fluid.

Oversight, Licencing and Enforcement: The Ministry of Energy and Resources oversees any mineral extraction activity. Beyond issuing licences, the minister has a wide range of powers that include – but are not limited to – implementing incentive programs for economic development, prescribing fees paid for information or services, or, with the approval of the Lieutenant Governor in Council, entering into agreements to purchase/sell any primary production in Saskatchewan Outside of mineral rights, the Oil and Gas Conservation Board investigates matters pertaining to the OGCA and oversees the protection of the environment. Lastly, the Water Security Agency has the power to issue Water Rights Licences. Each organization listed has the right to investigate any property where rights have been granted and impose penalties and fines in instances of non-compliance

Royalties: There is no royalty framework in Saskatchewan at the moment. However, mineral royalties exist, subject to a 10-year royalty holiday and an exemption until a payer has recovered 150% of its initial costs of exploration and development. The applicable rate is 5% of precious metals sales less than 1,000,000 troy ounces and 10% beyond that threshold.

Case Study:

Saskatchewan’s DEEP Earth Energy Likely to be Canada’s First Major Geothermal Producer

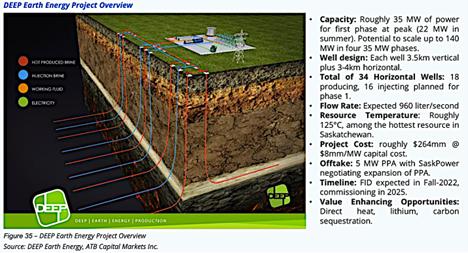

DEEP Earth Energy Production aims to become the first major geothermal power producer in Canada. The Company’s vision is to build out 140 MW of geothermal power and direct heating infrastructure in a series of scalable and repeatable 35 MW phases utilizing hot aquifers (roughly 125°C) in SE

Saskatchewan’s Williston Basin, targeting the Deadwood formation.

DEEP is currently developing its first 35 MW power plant (minimum 20-25 MW during summer). At roughly $8 mn per MW, we calculate a total capital cost for the initial phase to be roughly $280 mn The initial phase will produce hot brine from 18 purpose-drilled horizontal production wells producing at roughly 960 litres/second, reinjecting cooled water into 16 horizontal injection wells. As currently designed, DEEP will drill long-reach horizontal wells each expected to have a lateral length between 3,0004,000 m and at a vertical depth of roughly 3,500 m – when completed, these wells will be among the deepest wells ever drilled in Saskatchewan. The associated power plant will utilize ORC (binary cycle) technology to generate power.

The project was slated for a final investment decision (FID) by the fall of 2022 and it will likely coincide with a pending expansion of DEEP’s current 5 MW Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) with SaskPower (the regional utility) to meet the roughly 35 MW capacity of DEEP’s first phase.

Following a successful FID, DEEP is targeting a 2025 commissioning for its initial phase development In addition, DEEP is also looking to secure additional funding past the roughly $59 mn currently raised. DEEP has engaged GeothermEx, a Schlumberger company, as a consultant through the feasibility and FEED stages of the project, and GeothermEx will review DEEP’s subsurface engineering work DEEP notes that GeothermEx is a global authority on geothermal due-diligence, and the GeothermEx report is the “gold standard for geothermal investments”, leading to over US$14 bn in cumulative geothermal project investments representing roughly 8.5 GW of power capacity globally.

DEEP illustrates the diverse sources of funding available to geothermal projects. While the company is not public and does not file any financial statements, public sources show that the initial plant has received funding from the following sources:

Emerging Renewable Power Program: $27.6 mn grant for delineation work

Energy Innovation Program: $0 35 mn grant for research, development, and other activities

Innovation Saskatchewan: $0.2 mn grant for research and development

SaskPower and Natural Resources Canada: $2.0 mn grant towards prefeasibility studies

PHX Energy Services Corp.: $3 0 mn equity, with provision for $3 5 mn upon warrant exercise

Unnamed private equity investor: $25.4 mn equity over the past two years (as of September 2021)

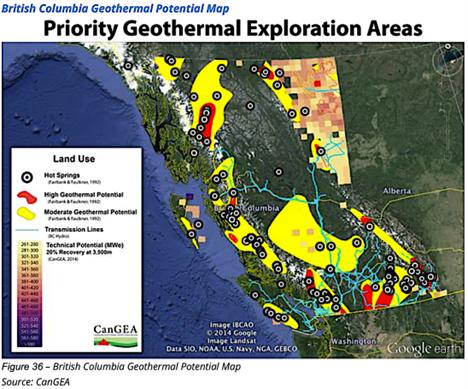

BRITISH COLUMBIA, CANADA

British Columbia has a variety of areas with medium- and high-quality geothermal resource potential. Despite this resource, there are only a few proposed geothermal developments in the province that we are aware of – the most notable of which is the 7-15 MW Tu Deh-Kah Geothermal project (formerly known as the Clark Lake Geothermal project) near Fort Nelson, BC

British Columbia Regulatory Regime

BC has a long-standing regulatory framework for geothermal resource development that is administered under the Geothermal Resources Act (GRA), which has been in place since 1996. The GRA addresses issues related to defining resources, resource use and ownership, licensing, liability, and oversight.

Geothermal Resource: Unlike Alberta’s GRDA, the GRA casts a wider net when it defines geothermal resources. Essentially, the definition includes any substance that is heated by the natural heat of the Earth regardless of depthdepth as long as it is 80°C or higher, including water, steam, and water vapour, and it includes dissolved substances in any of the aforementioned conduits, but it excludes hydrocarbons As such, lower temperature geothermal resources (below 80°C) would likely fall under the Water Sustainability Act (2014), which does not have a prescribed regulatory framework for geothermal developments.

Resource Ownership and Access: Unlike Alberta, ownership in geothermal resources in BC is held and vested by the provincial government, and they are thus solely allocated by the provincial government – all geothermal resource developments in BC must seek a lease from the provincial government In contrast to Alberta, geothermal resource developments in BC do not need to obtain mineral resource rights. In terms of surface facility and access rights on Crown land, a development may seek authorization through the BC Oil and Gas Commission (BCOGC), and for private lands, developments would be required to make private access agreements or seek a right of entry order from the Surface Rights Board if a private negotiation is not possible.

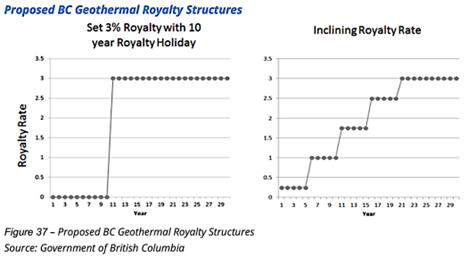

Royalties: The GRA also outlines that royalties and/or unitization will be paid to the provincial government – royalties may be negotiated with the government or, if not negotiated, would default to the prescribed rate. While the royalty framework continues to be developed, the BC government has published a royalty policy proposal which puts forth two potential royalty structures First, a 3% royalty rate following a 10-year royalty “holiday” period, and alternatively, an inclining royalty rate which begins at 0.25% and increases by 0.75% at five-year intervals to a maximum 3% rate (see Figure 37).

Oversight, Licencing, and Enforcement: The BCOGC has responsibility for oversight of activities involved in the production and injection of geothermal water, related pipelines, and associated facilities. After participating in a competitive bidding process for subsurface tenure from the Ministry of Energy, Mines and Low Carbon Innovation, project partners must apply to the BCOGC for permission to drill a geothermal well. Additionally, the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development has delegated its role in regulating access to land and other protective actions to the BCOGC.

International

Global Build-Out Yet to Hit Stride: There are pockets of the world where geothermal makes up a larger share of the power generation mix, but geothermal has not been built out at an appreciable scale globally.

At the end of 2021, there was roughly 15 GW installed worldwide, which covered less than one percent of the roughly 22,848 TWh of electricity consumed in 2019 (IEA estimate). Moreover, only 29 countries had any geothermal capacity installed – though ThinkGeoEnergy estimates that number could reach 82 with ongoing and planned development

According to ThinkGeoEnergy and IGA, there is roughly 200,000 MW in potential power generation capacity if low-grade heat and EGS are utilized (see Figure 38), suggesting that there is significant room for further development.

This is the final article in a series on how Geothermal Energy can impact the energy industry and net-zero transition. We hope you have enjoyed this comprehensive review of this topic, brought to you by CHOA and ATB Capital Markets Inc.