12 minute read

Connecting Alumni in the Classroom

Connecting Alumni in the Classroom

By Susanne Davis

The soul-shifting experience of inspiration often precedes human advancements and drives us forward to new levels of achievement.

At Choate, teachers engage students in the deep inquiry associated with inspiration to create this kind of transformational learning. Choate’s academic environment provides dynamic engagement with texts, collaborative learning, and individual inquiry. But, on occasion, the School goes one step further to add to the alchemy — connecting alumni to students’ learning.

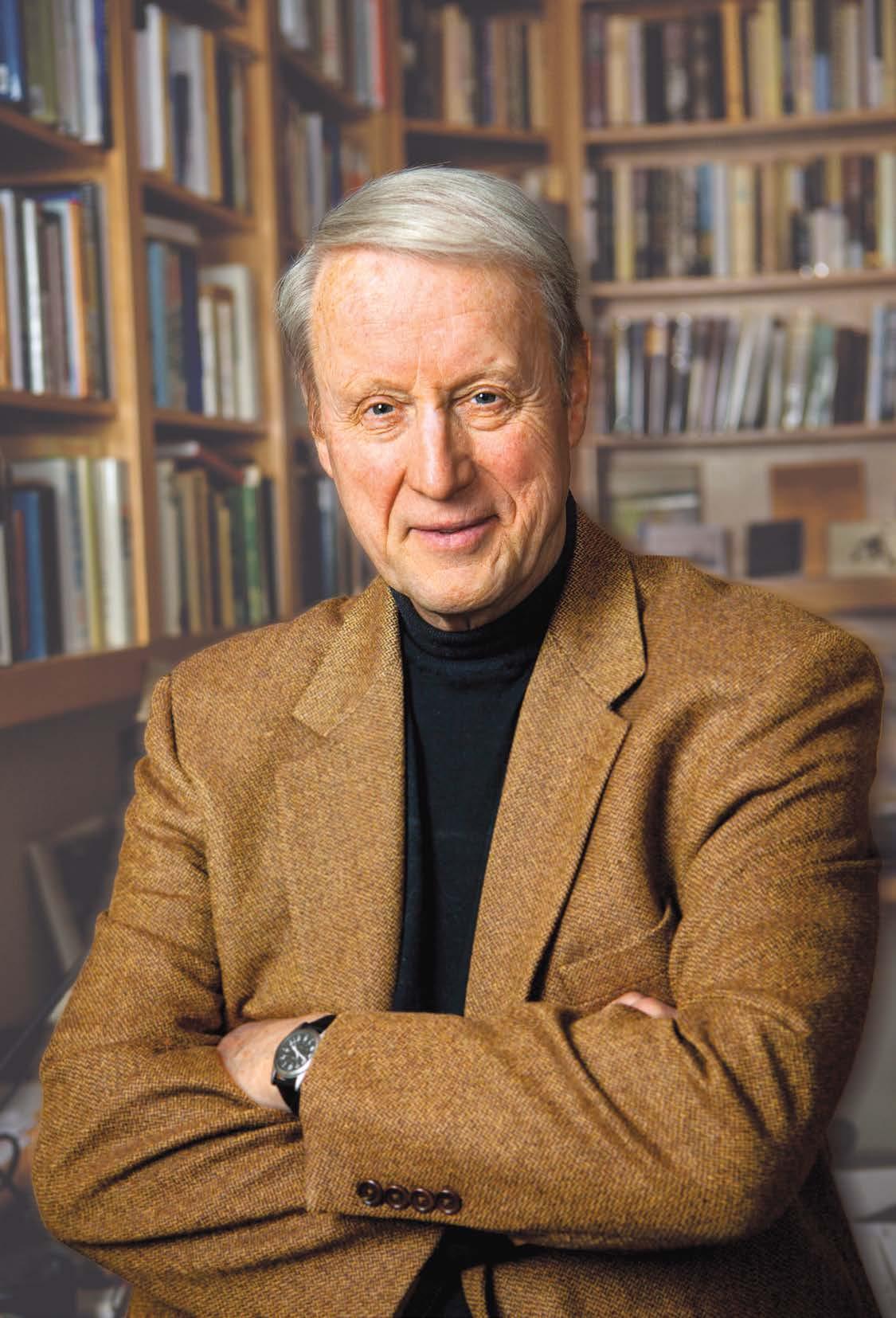

This academic year, the Bulletin offers a series to look at how teaching happens here, peering through the lens and stories of three inspiring alumni to see past, present, and future. Featured in this issue, two-time Pulitzer Prize winning former New York Times reporter and Emmy award-winning producer and correspondent Hedrick Smith ’51; in winter, cybersecurity expert and technology visionary, Window Snyder ’93; in spring 2024, Diversity, Equity & Inclusion expert Natalie Egan ’96. Through their stories and experiences back on campus, they contribute to and help highlight the extraordinary teaching at Choate.

HEDRICK SMITH: PAYING ATTENTION TO HISTORY

For 70 years, Hedrick “Rick” Smith’s formidable reporting skills have taken him all over the world. In 26 years with The New York Times, Smith covered Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights struggle, the Vietnam War in Saigon, the Middle East conflict from Cairo, the Cold War from both Moscow and Washington, and six American presidents and their administrations. In 1971, as chief diplomatic correspondent, he was a member of the Pulitzer Prize-winning team that produced the Pentagon Papers series. In 1974, he won the Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting from Russia and Eastern Europe. His 2012 book Who Stole the American Dream? was hailed by critics. He is at work on a new book about the story of our times.

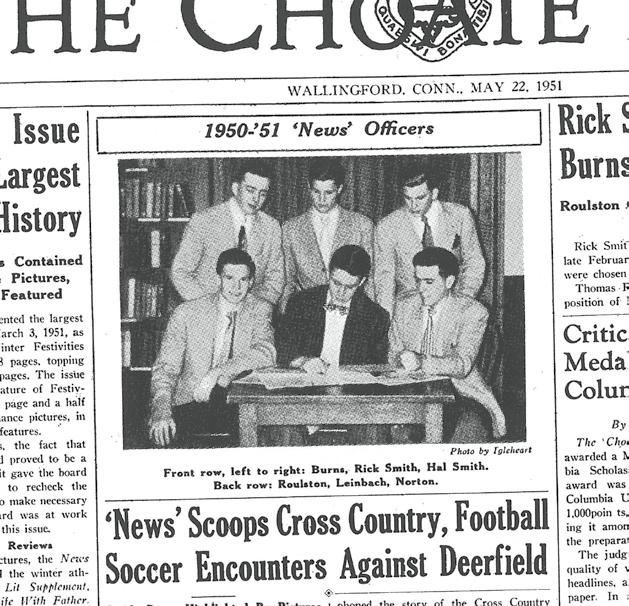

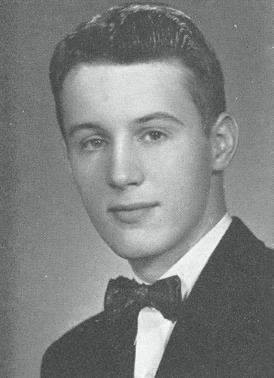

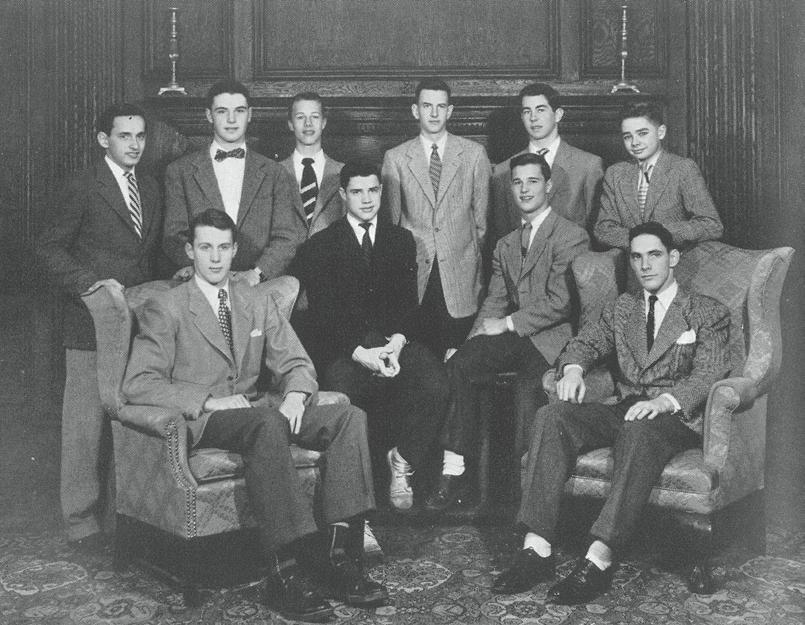

As a student at Choate, Smith was Editor in Chief of The Choate News.

He remembers the moment he felt inspired to follow his path. “It happened at Choate,” Smith says. “In a history class taught by Burge (C. Burgess) Ayres ’38. Burge knew I was running The News and he suggested I look at the muckrakers (reform-minded journalists of the Progressive Era of the U.S., 1890s–1920s). Lincoln Steffens, Ray Baker, Ida Tarbell, and William Allen White immediately became heroes of mine. What inspired me was that they were not just out to show the criminality of political corruption, they were looking at systemic issues of labor suppression, of economic corruption, of unfair trusts.”

Smith’s curiosity about how systems work and how they fail has driven his reporting throughout his entire professional life. “What is communism like? What works? What doesn’t? What can we learn from what works and what doesn’t?” He has applied that same kind of systemic questioning to American politics and to the economy, as well. “I’m looking for the big picture through concrete examples.”

By covering stories this way, Smith explains, his education has gone on forever. “Curiosity drives me.” There is no question in his mind that the suggestion from Ayres to read about the muckrakers was a major influence shaping him — “the idea that journalism can make our country and our politics better.”

Smith’s return to Choate last spring marked his first time back to campus since accepting the Alumni Seal Prize in 1981. “I was thrilled that the School asked me. I’d had the fun of interacting with the JFK (John F. Kennedy Program in Government and Public Service) kids in Washington. I was impressed with the caliber of questions, the curiosity, and their savvy.”

Head of Student and Academic Life Jenny Karlen Elliott saw how many students lined up to talk to Smith during that Washington trip and invited him to campus. She had to revise the itinerary — it wasn’t full enough, he said — to include three class visits, a meeting with The Choate News staff, lunch and a later afternoon drop-in for any interested students, a walking tour with Head of School Alex D. Curtis, and a dinner with the JFK Program students.

STUDENTS ARGUE MOCK SUPREME COURT CASE INVOLVING SMITH AND THE NEW YORK TIMES

When Smith visited Ned Gallagher’s Constitutional Law class, students were arguing two Supreme Court cases, The New York Times Co. v. United States (Pentagon Papers case) and United States v. Caldwell. Smith had been involved in the NYT v. U.S. case and knew the reporter involved with the Caldwell case.

“I couldn’t believe it was high school kids arguing those cases,” Smith says. “They gave sophisticated, college-level argumentation, and it was thrilling.”

At Choate, the upper-level history class is popular with students. The first half of the term covers an overview and the major themes of constitutional law from 1787 to 1937; the second half is designed as a mock court covering three dozen landmark Supreme Court cases. Gallagher explained that each student in the class is assigned to a case — to write briefs and summarize the case; the rest of the class reads the briefs and hears the oral argument.

Teaching reaches a “quality engagement” for Gallagher when kids talk to each other and listen to each other. “What I do is set up a situation and prepare kids, so their contributions are high level. In the second half of the Constitutional Law course the kids take over.” Gallagher says he’s

always been a political junkie. “But truly, I’m standing on the shoulders of giants. I give full credit to the colleagues who preceded me.”

“What Hedrick Smith contributed that day was incredible,” Gallagher adds. “New York Times v. U.S. was a milestone freedom of the press case, and he was part of it. He knew both cases, and the people involved.”

Julen Payne ’24, a student in the class says, “That day was special. Mr. Smith went into depth about the cases; they were pertinent to him. He gave us a firsthand view of history. You don’t really get to see the people involved in historical events, but that’s what is special about Choate. Choate alumni are those people.”

Regarding Smith’s comments on the caliber of student presentations, Payne muses, “That’s only possible with kids who are at that level. Putting kids in the shoes of lawyers and justices allows us to get new perspectives. We’re learning history, but we’re also pretending to be part of history. Teachers here make the way they teach really unique.”

Payne’s focus of study is economics, not history, but he appreciates being able to “take interesting classes.” His learning extends beyond the micro and macroeconomics he says other high schools offer; this year he plans to take Developmental Economics, International Economics, and Behavioral Theories. “We’re allowed to go deeply into something. There’s always another rabbit hole to go down to pursue our passions. We never hit the floor at Choate.”

IN ANOTHER CLASS, STUDENTS DISCUSS SMITH’S DRAFT BOOK CHAPTERS ON VIETNAM

In Jenny Elliott’s The U.S. in Vietnam (1961–1995), students read in advance two draft chapters of Smith’s book-in-progress, and came to class with typed responses, prepared to talk about it with him.

“The students were honored that Hedrick wanted their opinions,” Elliott says, “The chapters he shared dealt with his coverage of the Vietnam War and reflections about its long-term implications. It was perfect for what we’d been studying.”

“What the students in Jenny Elliott’s class shared as responses to the material was more personal than in Ned Gallagher’s class, they asked smart questions, and they were at a level of civic engagement that I couldn’t believe. That’s partly a sign of the times,” Smith says, “but also a credit to Choate.”

The students’ questions to Smith included:

“How did reading the Pentagon Papers change your view of government?”

It didn’t, Smith answered, because his view had already changed. “The sergeants and majors in the field in Vietnam were already telling us reporters that the U.S. was losing the war, contrary to what the government was telling the American people.”

“What impact did the publishing of the Pentagon Papers have on American public opinion?”

Smith painted a picture for students. “By 1971, tens of thousands of guys your age had burned their draft cards. I was at Harvard in 1969 to 1970 and the campus was aflame. Nationwide, the public was fiercely divided over the war. The long-term effect was an erosion of trust that the American people felt about our government.

“The Pentagon Papers were a watershed. They had an ever-larger impact on that erosion of trust in government, than on the conduct of the Vietnam War, and sadly, the erosion of trust has continued to this day. We need to understand our history better — for example, to see the longterm consequences of our mistakes in Vietnam, because what we don’t understand, we’re likely to repeat.”

WAKING STUDENTS UP. “IT’S YOUR LIFE,” SMITH TELLS THEM

Smith’s 2012 book Who Stole the American Dream? analyzed how, over four decades, our nation became two Americas with growing economic inequality, the super-rich 1 percent vs. the 99 percent, and the rise of political polarization and the political tactics of dark money, gerrymandering, and vote suppression. In Jonas Akins’ Democracy, Media, and Politics class Smith urged students to pay attention “because these issues will affect your lives.”

He provoked a conversation designed to wake them up to their own power and stressed the importance of their civic engagement to their personal futures and the country.

“I’m trying to shake you up,” Smith told students.

There are all kinds of things going on in our system with people and parties trying to ensure a lock on power. To take our democracy back, we need your participation.

When he asked students their impressions of democracy and one answered, “Democracy can be skewed based on wealth, power, and access,” Smith shot back, “Money is how it’s played. But what kind of money?”

“Dark money,” the student replied.

“But why does dark money matter?” Smith pressed. “Because politicians don’t want the public to see whom they are getting money from. They are hiding that connection,” he said.

As the conversation progressed into the issue of political polarization, students asked, “Do you hold media responsible for any of this?”

“Absolutely,” Smith said. “I hold the media responsible for a major role in the polarization of politics which makes them unworkable. By highlighting conflict and extreme opinions, the media is making this a much less governable country.”

He pointed to the different impact of social media from traditional media and the laws governing them both. “If you say it in The New York Times, or on PBS, it has to be true, or you can be sued. There is no libel law that applies to Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, nor Instagram. Algorithms drive their sites. These entities have no legal incentive to be honest. Congress passed a law that exempts them. That law should be abolished.”

The Choate News Editor in Chief Lauren Kee ’24, who is considering whether to pursue media and journalism in the future, says “Mr. Smith was in my role as Editor-in-Chief of The News 70 years ago, and being in the same room together was so surreal. I particularly enjoyed hearing about his experience with the newspaper ... I appreciated that he took the time to hear about our personal thoughts regarding our work on The News His thoughtful insights on the current state of the media in the face of technological advancements and political polarization were intriguing and valuable.”

History has lessons to teach us and guide us, according to Smith. His new book looks back over six decades: “How did we get where we are? It’s an effort to get Americans to focus on history, to understand the roots of our current problems. We think what is happening right now is the most important thing, and we say, ‘How will we get through this?’ History gives you insights, it gives you a footing, it gives you values. In a lot of ways, it gives you hope. If you think about what Lincoln went through, or our nation during World War II — we have examples from history to give us hope.”

Secondly, Smith is conveying the historical lessons of culture. “The Russia I covered in the 1970s and today, if I did my job well, should mean Putin is no surprise. Same thing in the Middle East. This is not a memoir about me. It is about what I saw. And it is important to see what went wrong, what went right. We can’t hide from history, but we can learn from it.”

On issues of economic and political reform, Smith suggests that people of retirement age can work well with young people by sharing their experiences with reform and civic engagement. “Hope requires engagement. We who are retired and the younger generation, aged 20–35 and younger — our generations are more hopeful in general, and can be more engaged in working on issues.”