7 minute read

Our Fundamental Home: The Landscapes of Patrick Cullen

from Patrick Cullen

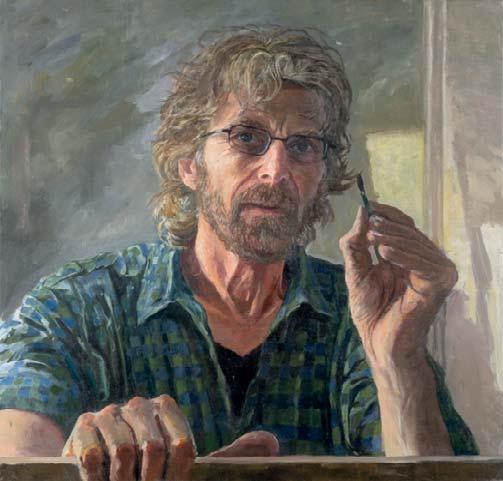

In looking at the works presented in this catalogue, and in the exhibition that it accompanies, it should be clear that Patrick Cullen is an artist of versatility. This becomes obvious on discovering the two searching self-portraits, painted at the ages of 50 [1] and 70 [2], which sit among the landscapes. However, it is in closely examining the landscapes themselves that his range reveals itself most profoundly.

Patently, there is a geographical span, from the allotments of North London to the heights of Annapurna, and Patrick Cullen’s initial encounter with a place has often marked a new stage in the development of his art, as his paintings and drawings of Tuscany, India and Nepal divulge. Nevertheless, it is his ability to discern variety within a place, and then to articulate it so sensitively over repeated visits, that is particularly telling.

Patrick Cullen is acutely aware of the many and subtle changes that occur, both over a day and across the seasons, to the land itself, to the light and weather that a ect it, and to the lives of the people who inhabit and cultivate it. This awareness is informed by his belief that ‘the countryside, the outdoors, the earth itself all represent our fundamental home, where as a species we evolved and as individuals we will eventually return’. It is also in uenced by his concern ‘to capture something elusive and fragile and now perhaps increasingly under threat by human destructive activity’*. His landscapes certainly succeed in capturing the subtlety and delicacy of the environment, and, partly inspired by the example of that modern French master, Pierre Bonnard, do so in an intense and often joyful way, so celebrating as well as scrutinising ‘our fundamental home’.

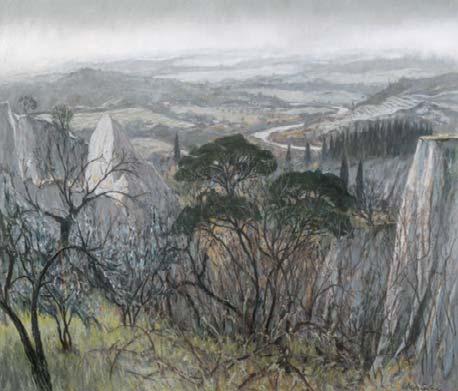

Patrick Cullen was already an established artist when, at the close of the 1980s, he visited Tuscany, and responded wholeheartedly to its terrain. While its agricultural pattern and implied human presence suggested to him a large-scale version of the London allotments that he had been painting, it o ered him much that he had failed to nd in England. Its undulating geography of high hills and broad plains allowed his eye greater freedom to roam, and provided it with an endless wealth of visual stimulants – formal, textural, tonal. Its timeless, traditional character also appealed to him, and brought to mind the elements of nature glimpsed in the backgrounds of many a Renaissance masterpiece.

As a result, Patrick Cullen has returned frequently to the area between Florence and Siena, and has engaged constantly with it – by walking, looking and then sketching – in order to express his deep feelings about landscape. He has visited at various times of year in order to appreciate the distinct qualities of each season, and has particularly enjoyed the contrasting palettes of spring and autumn [32 & 33]. Equally attuned to the shorter diurnal rounds, he has revisited motifs at di erent hours of the day, such as vines both early in the morning [23] and late in the afternoon [38]. He has also been keen to record the e ects of changes to the weather, from the saturation of strong sunshine [28], through the soft veil of a mist [25], to heavy rain draining a scene of bright colour [43].

1 2

32 23 28 43

The topography of Tuscany has inevitably encouraged Patrick Cullen to take advantage of the many high points that look down and out across a patchwork of elds bisected by roads or rivers [26, among others]. However, he is always keen to try out other, more unexpected, views, such as up a steep vine-covered hillside to a farmhouse high above [31] or through vegetation, a theme that gives rise to a series of singular variations, from one dominated by an unkempt copse [40] to another featuring burgeoning peach trees [17]. All of these approaches help lure the viewer fully into each landscape to share something of the artist’s own experience.

Though Patrick Cullen has said that ‘over the years, I have found myself less and less drawn to the landscape of my native England’*, his extensive engagement with favourite places in Southern Europe has enabled him to treat his home ground with renewed vigour. Compelled by the constrictions of Covid, he has recently worked in the counties of Southwest England, and elicited from them a sense of nature at its freshest and most vital. Apple trees burst into blossom at Hadspen, in Somerset [9], and the path down to Seacombe, in Devon, appears invitingly untrodden at dawn [14], while the towers of Corfe Castle, in Dorset (a worthy equivalent to those of San Gimignano [30]), are edged by the morning sun [11].

While Patrick Cullen could continue inde nitely to nd arresting ways of presenting now familiar subjects, he has been encouraged by fellow artists, and especially by Tim Scott Bolton, to travel to new destinations, and take on new challenges. So, since 2002, he has worked in India, while, in 2019, he visited Nepal.

26 40

9 11

56 54 52

In arriving in the town of Bundi, in Rajasthan, for the rst time, Patrick Cullen found himself in the midst of teeming human life. In contrast to his approach to European subjects, he chose to make this human presence explicit, and central to his imagery. As a consequence, he has focussed on people interacting with their surroundings, whether in the streets [56 & 54] or at the temple [52]. In so doing, he has fully absorbed and communicated the strong visual impact of this way of life, employing a heightened palette and introducing greater contrasts of colour and texture. This is well exempli ed by his responses to the market at Jodhpur, in which highly patterned umbrellas punctuate the air while casting pools of shadow across the ground [55 & 57], and bright oranges glow like hot coals [58].

The decision of Patrick Cullen to engage with such populous places in India, rather than to seek out its uninhabited landscapes, may be due in part to the country’s more traditional way of life and, as a result of its systems of belief, to the awareness of a cycle of existence among its people. In returning to India over the years, he has explored this trait more fully, in visiting such spiritual centres as Varanasi (sacred to Hindus) and Palitana (sacred to Jains). While conjuring up the sensuous splendour of these places in his images, he has also imbued them with a sense of deeper meaning. In painting The Last Journey [61], he has gone further in his re ection on those deeper meanings, and, as he explains in his own note to the work, has produced what is for him an unusually ‘conceptual piece’ that reimagines the ‘scene above Palitana … as an ascent towards oblivion or just possibly enlightenment, the distant Jain temples now replaced by the vast remoteness of the Himalayas vanishing into the clouds’ (see page 58 for the full note).

The Last Journey contrasts with most of Patrick Cullen’s Indian works in appearance and mood, and has been a ected by his recent visit to Nepal. For, while the busy urban life of India can distract attention from the wider environment, that environment is ever present in Nepal. In many if not most of the artist’s images of the country, the snow-capped peaks of Annapurna dominate, and such small human communities as Manang and Pisang accommodate themselves to it. Spots of colour – temple roofs, prayer ags, the occasional tree – strike up conversations with the starkly beautiful setting that concern something beyond the visible. If Patrick Cullen’s Tuscany emphasises the Edenic comfort of our earthly home, then his Nepal emphasises its most fundamental existential qualities.

David Wootton

*These quotations are taken from Patrick Cullen’s unpublished statement, ‘Some thoughts about painting’.

55 58

61