1 minute read

In the Classroom: Ethics and Imagination

In the Classroom

HIGHLIGHTING A COURSE FROM OUR RICH CURRICULUM

PHILOSOPHY 495: ETHICS AND IMAGINATION | EXPERIENCING “POETIC KNOWLEDGE”

BY DANIEL MCINERNY, PhD

When we enjoy a novel, a movie, or a play, we often fall into thinking that this enjoyment is “mere” entertainment, a diversion from our workday lives, perhaps even an indulgence. We do not realize that engagement with stories can involve a form of knowledge, indeed, of truth.

In the fall of 2019, my fi rst semester at Christendom, I introduced a philosophy elective called Ethics & Imagination. In this course, we explore how works of art, and principally works of imaginative literature, serve as forms of real ethical knowledge. We do not turn to these literary works simply to give us examples of ethical truths. Rather, we turn to these works as embodiments of ethical truth that cannot be gained elsewhere—even from the works of the greatest philosophers.

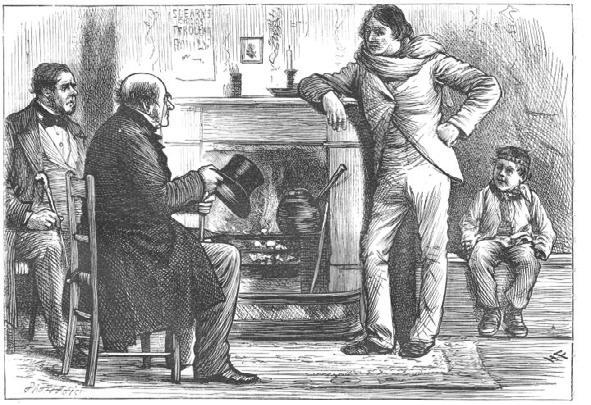

In Charles Dickens’ novel Hard Times, a harsh schoolmaster, Mr. Gradgrind, demands that a poor girl in his classroom, Sissy Jupe, give him the defi nition of a horse. Sissy, though she has grown up around horses in the circus, has no idea what the formal defi nition of a horse is. So another student, a boy named Bitzer, is called upon. He rattles off the defi nition of a horse:

“Quadruped. Graminivorous. Forty teeth, namely twenty-four grinders, four eye-teeth, and twelve incisive. Sheds coat in the spring in marshy countries, sheds hoofs, too. Hoofs hard, but requiring to be shod with iron. Age known by marks in mouth.”

Which one really knows what a horse is—Sissy Jupe or Bitzer? Sissy Jupe does not have Bitzer’s conceptual understanding of what a horse is, but she has knowledge of horses Bitzer does not have, what can be called “poetic knowledge,” knowledge based upon lived experience of horses. In Ethics & Imagination, it is this kind of knowledge about the human quest for happiness that we look for in the experience of great literature.

And in so doing, we partly attain one of the chief aims of a Christendom education: an interdisciplinary, unifi ed vision of truth.