Andreas Kofler, Goran Mijuk (eds.)

Christoph Merian Verlag

Andreas Kofler, Goran Mijuk (eds.)

Christoph Merian Verlag

Fabrikstrasse 6

Peter Märkli p. 64

Fabrikstrasse 4

SANAA p. 70

Fabrikstrasse 22

David Chipperfield p.128

Fabrikstrasse 18

Fabrikstrasse 15

Frank Gehry p.110

Fabrikstrasse 18

Juan Navarro Baldeweg p.166

Tadao Ando p.134

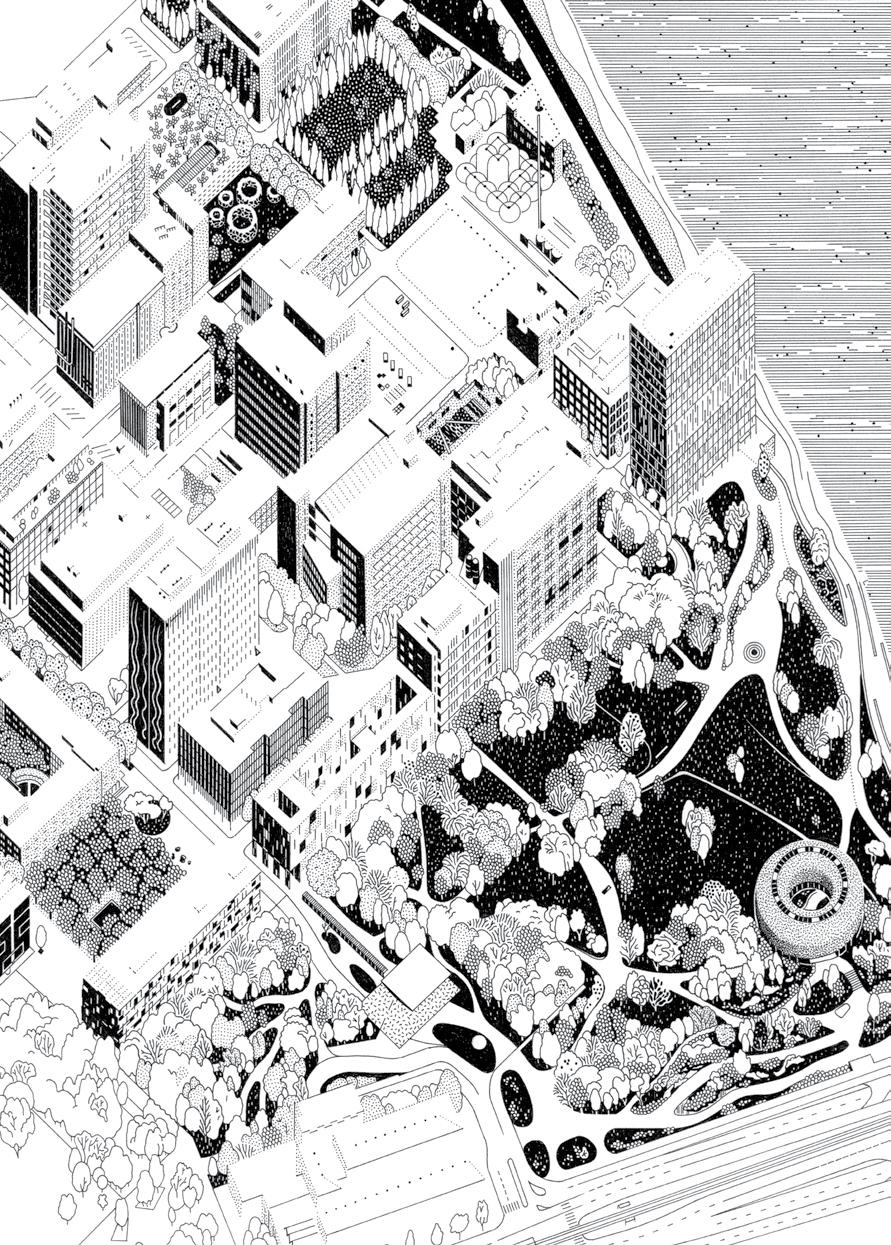

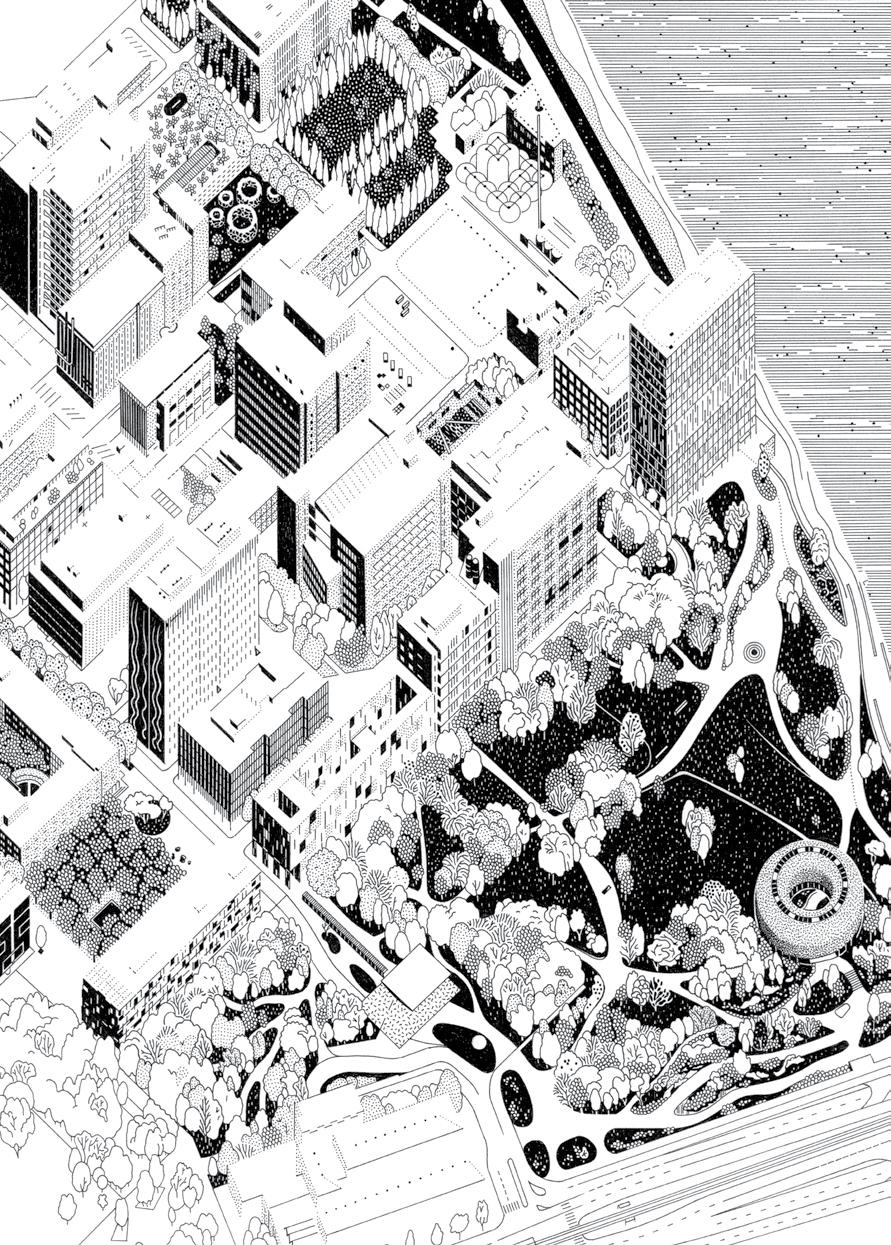

When planning for the Novartis Campus in Basel began in 2000, the aim was to transform an industrial production site into a center for scientific research and global administration. This change was already underway, but the challenge was to give it a viable, long - term urban and architectural form. That form should in turn create an attractive environment for the pharmaceutical company’s employees and, above all, encourage them to communicate with each other.

The model of the historical city seemed a natural choice. After all, the city is the ideal structural arrangement for shaping and honing a community. Its intricately branching structure of shared spaces not only creates direct relationships between different zones, but also offers opportunities for people to meet, both intentionally and spontaneously, thus fostering close interpersonal exchange.

In fact, at the start of the planning process, the open spaces served as crucial defining elements for the campus, providing the framework for its development. The dense orthogonal grid overlying the approximately 20 - hectare (50- acre) site dates to the ancient Celtic settlement that occupied large parts of it some 2,200 years ago.

The grid also adopts and discretely references the geometric ordering of the industrial area from the more recent past. It is no coincidence that the central axis of the campus still bears its original name, Fabrikstrasse (Factory Street). The axis leads to the French border, with cross streets extending to the bank of the Rhine. This basic geometry

When the companies Sandoz and Ciba - Geigy merged to form Novartis in 1996, a site the size of about thirty soccer fields in Basel’s St. Johann district became the new firm’s headquarters. Three years later, Daniel Vasella, its CEO at the time, commissioned Italian architect and urban planner Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani to draw up a master plan for the area’s urban redevelopment. The former industrial zone was to be completely overhauled and transformed into a “campus of encounter”. In keeping with the project’s complexity, several experts from fields adjacent to architecture and urban planning were invited to accompany the entire process. This planning committee was known as the Workshop. Serving alongside Lampugnani were the landscape architect Peter Walker, the curator Harald Szeemann (later Jacqueline Burckhardt) for art commissions, the British designer Alan Fletcher (later Michael Rock) for graphic design and Andreas Schulz for lighting design. The first projects to be implemented already embodied their collaborative approach and vision for the whole. The integration of art into the open spaces is just one example of this. This synergy facilitated the development of a place for working and researching defined by cooperation and communication. It was possible to turn Fabrikstrasse into the main spine of the campus by demolishing an existing parking garage and one other building. Other plazas and green spaces were gradually developed for this axis, sending a clear signal that the area would henceforth be a site of scientific research rather than industrial production.

Landscape Architecture Peter Walker (PWP Landscape Architecture) Implementation 2002–2003

Completion 2003

The former Sandoz administration building on the west side of Fabrikstrasse has a classical appearance, with two greenishgray limestone façades meeting in a corner block. It was built in 1939 by the Liestalbased architects Brodtbeck & Bohny in collaboration with Eckenstein & Kelterborn. Wings were added to the north and west sides after World War II. The building has enclosed a courtyard since then. Creating a small park for this enclosure marked the very first step in implementing the new master plan. Its designer Peter Walker was responsible for the overall landscaping concept for the entire campus. A grove of Himalayan birch was planted in the northern part of the court, taking a third of the rectangular space.

It replaced an old archive structure and an overgrown garden, among other things. The planting is sparse along the façades, with density increasing toward the center of the enclosure.

Today, at the southern end of the court, 24 hornbeams encircle a green space, creating a locale for employees to gather and relax. A long reflecting pool runs at the center of the courtyard, connecting the birch grove to the lawn enclosed by the hornbeams. Two paths paved in white marble intersect within the circle, bringing to mind a Swiss Cross. Light is mostly natural or enters the court indirectly from the surrounding buildings; there are also lights at ground level that can be adjusted for varying intensity.

Architecture Peter Märkli

Construction 2004–2006

Completion 2006

Use Office building with business center for visitors

Program Ground floor with two mixed - use open spaces and a café; five upper stories, one with meeting rooms and workspaces for registered visitors and four above it with offices; two underground levels with an auditorium

The building at Fabrikstrasse 6 was designed by the Swiss architect Peter Märkli. The offices in its upper stories follow the concept of Activity- Based Working, providing communal as well as individual workspaces, open zones as well as enclosed spaces. The ground floor and floor above it are open to business guests. The open design of the atrium at the heart of the building fosters communication and chance encounters among employees alike.

Märkli’s building has a prominent position next to the Forum, quite near the main entrance to the campus. It owes its design as much to the wealth of European architectural traditions as to the minimalist language of Modernism. Clarity and precision set the rhythm of the rooms and larger halls, which are interspersed with

marble - clad columns and wood - paneled ceilings and walls. An artwork by Jenny Holzer → p. 68 is integrated into the building’s Fabrikstrasse façade: a 3- meter- high LED sign bearing the texts of a thousand sayings and aphorisms collected from around the world.

The ground floor includes a café for employees and their guests. A central stair leads from this floor to meeting rooms and workspaces on the floor above. The ground level is suitable for group events, among other things: a zone called Cinerama can be closed off with a thick curtain for lectures or film screenings. A two - story auditorium, accessed from the lower of the two underground levels, features daylight and offers seating for 124.

The design oft the façade combines the rational structure of an office building with the aura of a cultural institution. (Sketch by Peter Märkli)

The ceiling of the colonnade is clad in cedar.

Niklaus Stoecklin’s large - format 1940 oil painting in the foyer— Chemiebild (Chemistry Painting) or Die Neue Zeit (The New Era) — showcases the pharmaceutical process, from the extraction of active ingredients from plants to the packaging of medicines.

Seamlessly joined Carrara marble, rare yew and olive wood, and deep blue carpets all contribute to an atmosphere of baroque opulence.

With its diamond - shaped aluminum structure, the railing Alex Herter designed for the stair echoes the frieze of rhombus shapes on parts of the façade.

Architecture David Chipperfield

Construction 2007–2010

Completion 2010

Use Laboratory building

Program Four upper floors, three with laboratories and one open floor with workspaces and a roof garden; two underground levels

A dense row of pillars lines the entire perimeter of David Chipperfield’s stringently geometric building. The British architect opted for an architecture in which the vertical lines of the pillars and the horizontal lines of the floors are immediately legible on the façade of almost white reinforced concrete.

In this very central position within the overall urban grid, the architect realized a major project for the company: the Lab of the Future. In this new kind of work environment, research projects can be implemented quickly and efficiently. The columnfree floor plans can be flexibly used and configured, allowing different areas to merge fluidly with one another. This results

in a precise yet adaptable “laboratory landscape” that meets the different requirements of individual research projects.

Further developing the logic of the open lab that underlies Adolf Krischanitz’s nearby building → p.122 , the laboratory areas here are no longer separated by glass walls. The ground floor, 6 meters in height, accommodates a restaurant and a cafeteria. The roof garden on the top floor consists of a large, centrally positioned concrete basin filled with nearly fifty tons of green glass balls: the installation Molecular (Basel) by the artist Serge Spitzer. The trees growing within it are known as Japanese elm (Zelkova serrata).

The installation by Serge Spitzer, conceived as a “viral” sculpture that can change either at random or in response to external influence, includes a total of 760,000 glass balls.

The building accommodates interdisciplinary research teams: chemists and biologists work together on one and the same floor.

Artist Menno Aden’s work Lab, which hangs in the entry area, shows the building’s dynamic and open laboratory concept.

An additional staircase connects laboratories, offices, and the roof garden. Designed by artist and industrial designer Ross Lovegrove, its form resembles a spine.

The laboratory building at number 22 is the only new structure on Fabrikstrasse to feature a colonnade not only along its street façade but also on one of its flanks, in this case its north side.

Before 2001 there were just 18 trees on the entire St. Johann site. The transformation of the industrial zone coincided with a fundamental change in the world of work, one that was accelerated by digitalization. Interest rose in holistic workplace design with the aim of improving employee well - being. With this in mind, parks and gardens were conceived from the outset as an integral part of the Novartis Campus. Green spaces punctuate the building development, creating openings where staff can spend time in nature and recharge their batteries.

Today more than two thousand trees grace the campus, including many species like Norway maple, beech, and birch that are native to the region. The year 2016 saw the completion after several construction phases of Park South → p.188 , with its carefully planned impression of naturalness. It stands atop a former system of railway tracks that once led to the port, which was relocated upstream on the Rhine. Like all the other green spaces on the campus, it includes many works of art. Landscaping simultaneously began on the public promenade that runs along the Rhine — the riverside path linking Basel with Huningue on the other side of the French border. At a higher elevation on the campus proper, the elongated Rhine Terrace → p.194 was completed two years later. These bordering areas soften the perception of the site’s perimeter by linking it to the city as well as to the Rhine. Asklepios 8 → p.182 — the Herzog & de Meuron office building completed in 2015— stands at a height of some 63 meters where previously only production facilities could be seen. It provides a strong visual focus. As for the newly completed Novartis Pavillon → p. 200 , its location in Park South along with its role as the first building on the site to be entirely open to the public are symbolically important. The pavilion serves as an exhibition venue and a center for encounters. It shows how the history of the pharmaceutical industry is intertwined with the city of Basel, and it provides a venue for exploring essential issues for the future of the healthcare sector.

Artwork Olafur Eliasson

Developed 2007–2014

Installed 2014

Material Granite

Dimensions 92 × Ø1,040 cm

The Icelandic- Danish artist Olafur Eliasson began work in 2007 on a site - specific piece for Park South → p.188 , the landscape designed by Günther Vogt. Oscillation Bench, completed in 2014, is located near the bank of the Rhine. Organic in form, it appears to capture the moment when a drop meets a surface of water and ripples radiate out from it in concentric waves. This moment is “frozen” and materialized in Kuru granite from Finland. On closer inspection, it becomes clear that the abstract shape consists of a circular bench and table, essentially

making it a 67- ton utilitarian object. The double - sided bench seats about forty people, some on the inside and others on the outside, with visitors accessing the inner bench through a cut in the granite. By representing the ripple effect, the work stands for turning thinking into doing — thereby producing reality. Eliasson had a model of a similar bench built in his studio in order to observe how people made use of it— alone, with several random people present, and in a group.