35 minute read

Immigration Under Biden

by Chronogram

THE DEPORTATION OF PAUL PIERRILUS

By Michael Frank

Advertisement

A collaboration with

Recently constructed panels at the border wall near McAllen, Texas on October 30, 2020. Photo CBP/Jerry Glaser

In late January, the Department of Homeland Security issued a moratorium on deportations for 100 days at the request of the new president, Joe Biden. But a federal judge blocked it after Ken Paxton, the embattled attorney general of Texas, sued. For immigrants and immigration advocates, it was a painful reminder of the limits of the new administration to alter immigration policy with the stroke of a pen.

It was also a bitter irony. Paxton’s actions will undermine his own state’s prosecution of an alleged mass-murderer who killed 23 people at a Walmart in El Paso in 2019. A witness to that slaughter is a 27-year-old woman known as Rosa. Against her better judgment, according to reporting by the Washington Post, Rosa came forward to give key details to Texas state and federal authorities about the events of that day. But she also had a standing warrant for deportation, and a recent police stop for a broken taillight led to her being deported to Mexico, where she hasn’t lived since she was a child. Rosa was in the process of obtaining a U-Visa, which prevents crime victims from being extradited while they can offer critical testimony.

Why care about a case in Texas? Because Rosa isn’t alone. Paxton’s actions are having ripple effects far nearer to home, in Rockland County.

While Rosa was being detained, so was 40-year-old Paul Pierrilus, a financial consultant who has lived in the US since he was five. On February 2, he was deported to Haiti. Pierrilus isn’t from Haiti—his parents were born there, but he was born on the Island of St. Martin, and was never given citizenship there, either. He’s technically stateless, and, according to Newsweek, had been allowed to stay in the US under an order of supervision, which required he regularly check in with Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

But that changed on January 11. Instead of releasing Pierrilus from his check-in, ICE detained him, flew him to a prison in Louisiana, and began proceedings to deport him.

Freshman Congressperson Mondaire Jones, whose district includes Rockland County and parts of Westchester County, managed to prevent the initial attempt to send Pierrilus to Haiti on January 19, just 24 hours before Biden took office and the DHS issued the 100-day halt on deportations. But because that memo was blocked, ICE continued deporting people— including Pierrilus.

New Yorkers Pay for ICE

The Trump Administration passed over 1,000 rules and regulations concerning immigration, and despite a litany of actions in the initial days of the Biden White House, some of those ordinances are still in place. Perhaps most pernicious is a decision last March that allows border agents, under Title 42 in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention code, to expel anyone entering the country without due process under the guise of preventing the spread of COVID-19. A January 28 letter to the CDC signed by dozens of health experts excoriated the policy and called for its immediate removal.

The Biden administration has lately been applying Title 42 to most, but not all asylum seekers, allowing in more unaccompanied minors. However, recent reporting by Buzzfeed suggests that to stem that new surge, they might begin expelling 16 and 17 year olds under the edict. According to Customs and Border Protection data, there have been more than 515,000 “expulsions” (meaning without due process or any right to claim asylum) since the pandemic began; the advocacy organization Witness at the Border says there have been 110 ICE deportation flights since Biden took office and mid-March.

In a letter to Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, Representative Jones called for deportations to stop. He wrote that the Pierrilus case highlights ICE’s punitive and capricious nature, noting in part that “Pierrilus is not a citizen of Haiti…had never even been to Haiti, [which] is roughly 1,500 miles from the Rockland County, New York, community that has long welcomed Mr. Pierrilus as a beloved neighbor. In spite of these facts, ICE deported Mr. Pierrilus anyway.”

In a statement to The River Newsroom, Jones not only reiterated the danger ICE poses, but added that its relationship with prisons is corrupting. While Pierrilus was first sent to a facility in Louisiana, most ICE detainees in the region are held prior to trial at the Orange County Correctional Facility, in Goshen, which

receives $133.90 a day per inmate. The Goshen prison was paid $8 million from ICE service agreements in 2017 and 2016, according to reporting by the nonprofit immigration news site Documented. Jones argues that “detention should not be the default position for migration processing.” He seeks an end to the for-profit prison system in both state and local jails, “like the ones in which Pierrilus was imprisoned in Louisiana.”

There’s another reason to sever the relationship of New York’s counties and towns to ICE: money.

Jane Shim is a senior policy attorney with the Immigrant Defense Project in New York, which seeks broad changes in how the state and federal government directs its energies against immigrants. She points out that when local prisons work with ICE, they open themselves up to lawsuits when they allegedly restrict people’s rights on behalf of ICE. There have been many across the country, both against prisons and local police, such as a $14 million payment LA County had to make late last year. Currently there’s a class action lawsuit against the Orange County Correctional Facility and the Orange County Sheriff for unlawfully detaining people who, the suit argues, pose almost no danger if they were released back into their communities and asked to appear for hearings.

Based on a comprehensive 2019 study of ICE arrests undertaken by Syracuse University, the number of detainees who were apprehended for anything like a violent crime dating over the past six years is vanishingly small. Out of 500,000, a mere 68 people (0.0123 percent) were convicted of terroristic behavior. And as for Trump’s constant claim of gang activity, ICE managed to convict only 0.0149 percent, or 82 people. “Going back before Trump,” Shim says of ICE, “their agenda is to see community members as threats. To treat people as disposable.”

New York vs. ICE

While lawsuits against state and local prisons can feel like an abstract cost, taxpayers face a more subtle expense when local police work with immigration enforcement: detainer agreements between ICE and local precincts help train police, but ICE isn’t paying the salaries or pensions of those officers. Cops are now out working cases that, Shim makes clear, mostly have nothing to do with the safety of the public they were hired to defend and protect.

One state legislative solution, backed by the Immigrant Defense Project and local advocates like Nobody Leaves Mid-Hudson, is the New York for All Act, which would make it unlawful for police, court officers, parole officers, or school officers to work with ICE or CBP; would bar them from enforcing immigration law; and would prohibit passing information to federal agents without a judicial warrant. “Right now, somehow ICE gets wind of someone showing up for their court-mandated hearing,” Shim says. “Upstate, near the border, CBP gets alerted when someone gets pulled over for a traffic stop. This would put a legal stop to this collusion and collaboration.”

Shim says New York for All is necessary regardless of the fact that Biden issued a directive to DHS to limit its efforts to tracking down those guilty of “aggravated felonies.”

Paul Pierrilus of Spring Valley was deported to Haiti in February, even though he is not a Haitian citizen and had never visited the country. Courtesy of Neomie Pierrilus

Unfortunately, she notes that this falls to the discretion of both ICE and local law enforcement. “Too often what they arrest people for are neither aggravated crimes nor felonies.”

State Senator Julia Salazar, the bill’s lead sponsor, linked it to COVID-19 spread, arguing that blocking officials from passing data to immigration enforcement is key to giving immigrants more confidence in seeking health care. In a February 11 media briefing, Salazar described “Immigrant New Yorkers living in fear of going to a COVID testing site, or to get vaccinated out of fear of immigration enforcement.” Salazar also mentioned the rampant spread of COVID-19 in the Batavia facility that houses some ICE detainees (currently there are 54 cases) as one of the worst recent outbreaks of the disease in the state. During the same briefing, lead Assembly sponsor Karines Reyes made that connection clear, too, arguing that ICE’s tactics “burden state resources while undermining the state’s public health efforts.” Reyes noted the irony of government officials praising frontline workers, a disproportionate number of whom are immigrants, without actually doing anything to protect them.

The Bigger Picture on Immigrant Protection

Reyes’s words ring especially true to Emma Kreyche, an attorney in Kingston with the Worker Justice Center of New York, which focuses on worker rights, particularly in lowwage jobs where advocacy is critical. The organization is especially focused on two other state legislative actions.

One would establish occupational standards for exposure to airborne infectious diseases. “As an organization that focuses more on rural

US Customs and Border Protection operations after the implementation of Title 42 at the border. Photo CBP/Jerry Glaser

communities and on workers in industries like food processing and agriculture, we saw very early on in the pandemic that these were industries that were extremely hard hit by COVID,” Kreyche says. She cites an outbreak that hit 186 farmers in Oneida last spring because their living conditions didn’t allow for social distancing, but she says you don’t have to think about farming to understand why air quality standards are critical across the state. “Look at the back of the house of any restaurant or the hospitality industry and you see, whether you’re an immigrant or not, those frontline workers are endangered.”

“We do know, right, that Biden’s different from Trump,” says Diana Lopez, Ulster County community organizer for Nobody Leaves MidHudson. But she seconds Kreyche on how what is actually grinding on immigrants is the entire force of the pandemic—plus fear of arrest. “It’s not just ICE. It’s feeding your kid. It’s getting them the medical attention they need.” To that end, Nobody Leaves Mid-Hudson, in addition to Worker Justice, is meeting with Hudson Valley legislators to push for the Excluded Worker Fund Act, which would help workers who don’t otherwise qualify for unemployment. Lopez notes that would cover the undocumented, and also gig workers who live more on tips or seasonal workers who depend more on cash. “It’s house cleaners, people like that. I hear all the time from people who need help paying the rent, need to go to find a food pantry,” Lopez says. “People are really struggling and it’s heartbreaking.”

Some Sunlight

The federal government has distanced itself from some of Trump’s policies. Advocates for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals cheered executive orders that extended DACA benefits to two years and directed the United States Attorney General to defend the program. (The latter move is necessary because nine states, led by Texas, have argued that DACA is illegal; a US district court judge in Houston may rule as soon as this month. The Trump justice department didn’t defend the case in court.)

Biden’s longer-term legislative goal is to create a path to citizenship for the estimated 11 million noncitizens in the country, including DACA recipients. But he has already signed a number of executive orders in his first weeks in office that directly bear on immigrants in the US. The most symbolic of these is a halt of construction on the border wall. Biden also established a task force to try to reunite families separated by Trump’s Zero Tolerance policy; a Justice Department Inspector General’s Report out just a week before Trump left the White House found that policy leaders ignored advice that Zero Tolerance would lead to prolonged family separations and when that began to happen, ignored the devastating effect it had on families.

And Biden has already ordered a study and likely revocation of Trump mandates that prevented a legal path to citizenship if a person used any social service aids (the so-called “public-charge” rule), and the Supreme Court has since agreed not to hear a case that would have possibly upheld that Trump executive order. Biden also rescinded part of a Trump 2019 order that threatened US-citizen sponsors with legal action if they shared their own benefits with noncitizens. These included the most basic, subsistence aid, such as food and medical care for immigrant children. Biden also retracted Trump’s attempt to exempt noncitizens from the census, as well as Trump’s wielding of ICE within US borders (and Trump’s order to apprehend anyone with or without a criminal record).

It’s also likely Biden will end the so-called Safe Third-Country Agreement, which forced anyone claiming asylum in the US from having the right to stay if they’d passed through another nation on their journey to America, almost no matter what terror they had fled.

If that sounds abstract, it’s not. It’s life and death.

The “New Yorker Radio Hour” recently played audio from a court proceeding where a judge tells a woman that she has to take her daughter, who was raped in front of a police officer in Honduras, back to that country because of this Trump directive. The judge’s pained reading of the law is that the woman should have sought asylum in one of the countries she traveled through on her way here with her daughter; therefore, the US cannot protect her.

The case makes abundantly clear that the Safe Third-Country Agreement has been in complete contravention of the reason the US established asylum laws in the first place: that America would never send a person or family facing sure terrorism, death squads, or rapists, back to that place simply because they’d crossed a line on a map.

The Bottom Line

According to the Center for American Progress, DACA recipients in New York pay $315 million in federal taxes and $210 million in state and local taxes each year. They also pay a combined $128 million in rent and mortgage every year. (If you have DACA, you frequently live in a household of mixed immigration statuses, meaning these figures often reflect undocumented and documented immigrants footing these bills as a unit.) As Lopez of Nobody Leaves Mid-Hudson puts it, it’s time to honor those payments with aid. “Nobody can do it all by themselves. We all need community support.” Lopez says state lawmakers can make that happen, though she’s concerned that midHudson Valley representatives fear a backlash about helping immigrants.

But Lopez is also hopeful that empathy will win out. “Step up and help people who are hungry and hurting,” she says. “Do whatever it takes.”

As for Pierrilus, he arrives in a country beset by political protests that have been met by increasingly violent crackdowns by authorities. “Right now he’s not doing well, him being in Haiti for the first time,” says Guerline Jozef, cofounder and executive director of Haitian Bridge Alliance, a nonprofit organization serving Haitian and other Black immigrants in the US, and which is working to bring Pierrilus home to his family. “He is holding on, and we are fighting on his behalf.”

That fight isn’t slowing anytime soon. According to the Haitian Bridge Alliance, over 1,000 people were sent to Haiti in in February, including pregnant women and children. Hours before Jozef spoke to The River Newsroom, she had been fighting to stop a flight bound for Haiti that had children as young as 1 on board. While members of congress and advocates have managed to slow some of these deportations (most of which have been expulsions under Title 42), they’ve never entirely ceased.

“It is unconscionable for the US to continue deportations during the pandemic,” Jozef says. “We are calling on the administration to stop.”

BUILD BACK BRIGHTER

The revitalization of Newburgh is finally happening. But for whose benefit?

By Brian P. J. Cronin Photos by David McIntyre

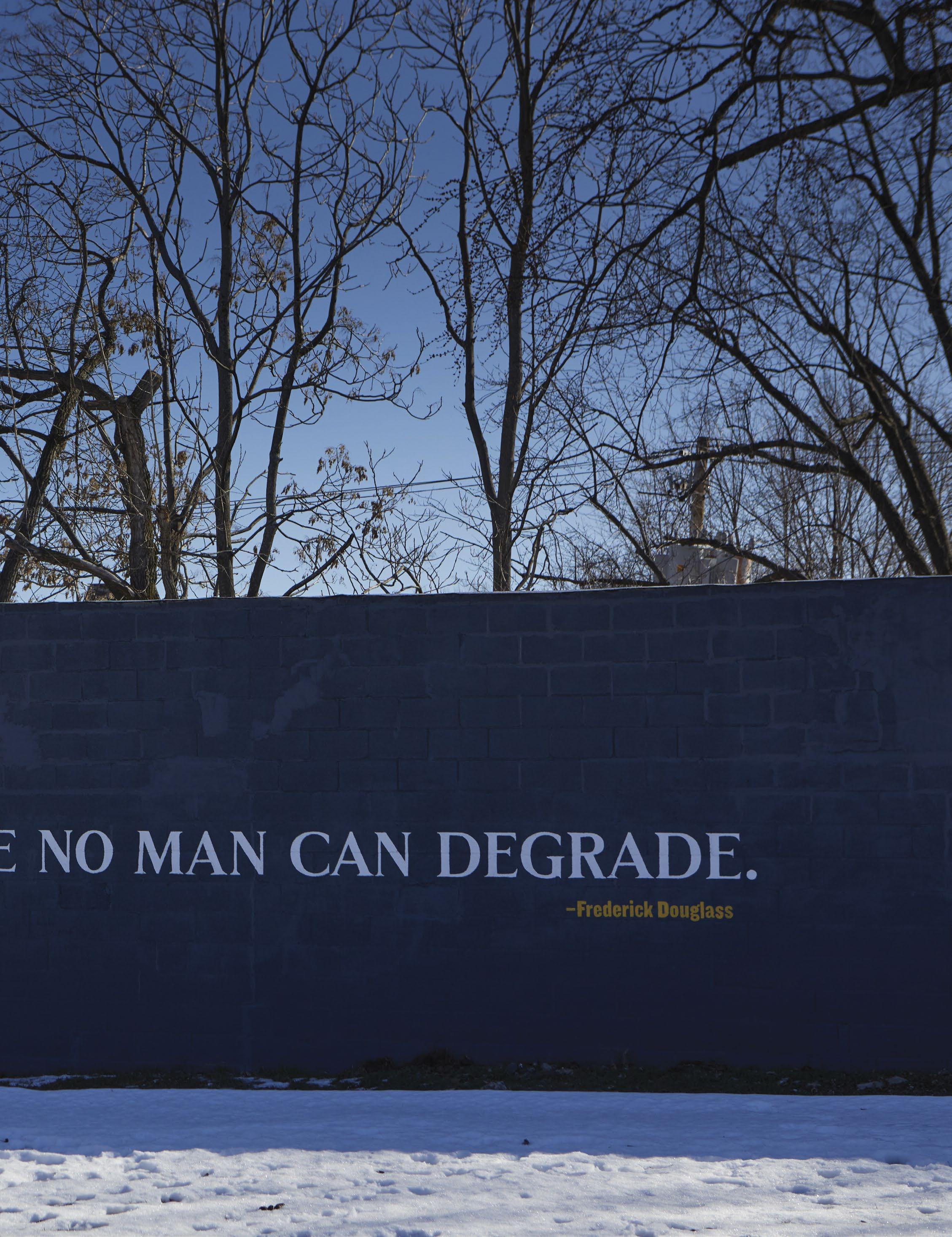

This mural on the side of a building between Liberty and Johnes Streets commemorates Frederick Douglass’s visit to Newburgh in 1870.

Mural in progress just off Broadway on Clark Street.

Twelve years ago I was participating in a community clean-up of a vacant lot in downtown Newburgh when someone found a deer leg. The rest of the deer was nowhere to be found.

The cleanup ended for the day shortly after that, on account of temporary demoralization.

That lot has since been transformed into a lush and sustainable urban park, complete with sculptures that double as public cell phone charging stations and massive, stately photographic portraits of Newburgh residents peering down from the wall of the onceand-future Ritz Theater. If you’re looking for one thing to symbolize the positive changes happening in Newburgh today, stand on the corner of Broadway (the widest main street in America) and Liberty Street (one of the hottest blocks in the Hudson Valley right now).

When Bryan Quinn, the owner of the environmental design firm One Nature and chief designer of the park, was working on the project, locals would often stop and ask him and his crew what was going on. He would reply that they were building a park. The response was almost always the same.

“For who?”

It’s an appropriate question. For decades, the message that the rest of the state had for the citizens of Newburgh, as its downtown crumbled, its infrastructure collapsed, and the city was hailed as “the Murder Capital of New York,” was: You’re on your own. Now new projects and new developments are making their way across the city.

To be clear, Newburgh still does have very real and very pressing issues. The city may have beautiful housing stock, but many of the elegant old houses, the ones that haven’t been outright condemned, are in disrepair and kept that way by landlords taking advantage of people in dire economic straits. And while the city’s notorious (though falling) crime rate is mostly a result of inter-gang violence confined to a few hot spots, that’s cold comfort to the countless mothers and fathers whose children have had their lives cut short on the city’s bluestone sidewalks, Newburgh’s future generations lost to the streets.

In a city in which tomorrow has seemed bleak for so long, the overdue influx of money and attention is welcome. But for many long-term residents, the question remains: Is Newburgh finally being lifted up? Or taken for a ride?

The Original Bright Spot

The fall of Newburgh is a well-known cautionary tale, familiar to anyone who’s studied urban planning. A dynamic, thriving city, the first city with an electric grid in America, Newburgh was knocked down by the one-two punch of an interstate highway (I-84, which bypassed the city) and urban renewal, which gutted much of downtown. But when Newburgh realized that outside help wasn’t coming, it rolled up its sleeves and got to work.

Houses of worship, parents, community activists, and social service nonprofits worked together to keep those hotspots of crime from spreading to the rest of Newburgh. The city’s waterfront was developed into a miniature village of eateries and spas, but with a towering hill separating the waterfront from the rest of the city, the economic effects of the development stayed on the waterfront. It’s a lovely place to spend an evening, but both geographically and culturally, it’s never felt like Newburgh.

The city’s fits and starts of renewal struggled to take hold until about 10 years ago, when a few things happened in close conjunction to one another. The Newburgh Community Land Bank formed and started getting abandoned properties fixed up and back on the tax rolls. The Newburgh chapter of Habitat For Humanity, which was formed by three long-time Newburgh residents sitting around a kitchen table in 1999, evolved into a robust nonprofit that’s since completed over 100 projects in the city. Safe

“I have no interest in running a restaurant in Newburgh,” says Leon Johnson of Lodger, who gives away more food than he sells at his non-restaurant.

“The reason Newburgh appealed to me is the same reason that some people don’t like it. It’s a real city with city issues. It’s not a quaint little upstate town. It’s a beautiful place with a nice mix of old buildings and great architecture, but it’s also a real place where people are trying to make a go at it.”

—Sisha Ortuzar Wireworks

Harbors of the Hudson took over a dilapidated single-room-occupancy hotel and turned it into safe and affordable housing for those who would otherwise be preyed on by Newburgh’s more unscrupulous landlords, and opened up a gallery and performance space as well. Around the corner on Liberty Street, the Wherehouse bar and restaurant opened, booking bands in the back. One block south, Newburgh Art Supply opened to cater to the artists who had begun arriving, attracted by cheap rents and ample space. The Newburgh Brewing Company started churning out award-winning beers in a former paper box factory, acting both geographically and culturally as a bridge between the waterfront scene and the city itself. Suddenly, people who didn’t live in Newburgh were coming downtown for a night out. Suddenly, Liberty Street was the place to be.

With the benefit of hindsight, Liberty Street was always the ideal place for Newburgh’s renaissance to begin. It’s a narrow, charming street dotted with small storefronts for blocks, many of which were empty. They didn’t stay empty for long.

Opportunity Knocks

“I have no interest in running a restaurant in Newburgh,” says Leon Johnson. It’s a pretty surprising thing to hear from someone who appears to be running a restaurant in Newburgh. But Lodger, located on the first floor of 188 Liberty Street in a former undertaker’s office, is, upon further inspection, operating in a strange, liminal space between a restaurant and something with a proximity to food that seeks to address a variety of social problems. The name itself, Lodger, also cheekily refers to a state of in-betweenness: Johnson moved here a few years ago and isn’t ruling out moving on in the near future. Even the space, an 1830s building that was raised in the 1880s when the streets were redone to fix drainage issues, has a transitory nature to it, as the filled-in fireplaces and closets hover just above one’s head. Johnson refers to the night-time atmosphere of the space as having a “Harry Potter Platform 9¾” vibe to it.

Lodger does, in fact, serve food, although until outdoor dining returns and the pandemic ends, that means limited takeout on Fridays and a $45 prix fixe on Saturdays. But if you do grab a table on Saturdays, you’re doing it in view of the food pantry next to the front door Johnson fills six times a day. When COVID struck, Johnson started cooking hundreds of school lunches every week until the school district could get back up to speed. He and his students (he takes on three at a time from the Newburgh Free Academy) also cook for the residents at the Exodus House behind their building, a nonprofit that houses people recently released from prison after longterm incarceration and who are slowly making their way back into society. “We give away more food than we sell,” says Johnson.

Sisha Ortuzar, developer of Wireworks, a recently opened mixed-use space at 109 South William Street.

We’re interrupted by hammering next door, where the former headquarters of the local NAACP chapter has been recently bought by an investment company and is being renovated. We talk about the rumors of investment companies from New York City who are planning on buying hundreds of Newburgh properties over the next 12 months. (I reach out to one such company, who touts Newburgh on their website as being “an ideal location for new investments,” the next day for confirmation, and am ignored.) Johnson notes that in the past few months, more than half of the diners at Lodger are people who had just moved to Newburgh from New York City.

“I came here from Detroit,” says Johnson. “I know what this means. The same dialogues are happening.”

If Newburgh’s revival is still years behind the booms that other cities in the Hudson Valley have gone through, that lag time has given the city a chance to learn from other’s mistakes. Namely, the point at which improvement goes through the looking glass and comes out the other side as gentrification, displacing the longterm residents who made the revival possible in the first place. Some of those mistakes have benefitted the city directly, as the owners of many of Liberty Street’s eateries are in Newburgh because Beacon, just across the river, has become unaffordable. But as Newburgh welcomes developers who are finally showing interest in the city, it’s also making sure not to be too welcoming.

“We have a lot of interest from developers to do something here, and we need to make sure that it can happen in a way that’s not to the exclusion of people who currently live in the city,” said Austin DuBois, who is the head of the city’s Industrial Development Agency and also serves on Newburgh’s new Strategic Economic Development Advisory Committee. “A lot of places can pave over a farm or sell out to a developer. And while we want to welcome and accommodate development, we want to be responsible and make sure it helps the people who already live here.”

Back at Lodger, I ask Johnson what newcomers to the city can do to make sure they’re on the side of positive, as opposed to negative, change. “I’m not convinced that’s a binary question,” he says. “I don’t think I’m on the right side, and I don’t think I’m on whatever the wrong side is. But I would situate my answer around: What is the nature of your contribution? What are you contributing to besides the tax base?”

Real City, Real City Issues

Like a lot of people who move to the Hudson Valley, Sisha Ortuzar was looking to get out of New York City. But unlike a lot of those people, the former chef who cofounded the ’Witchcraft series of restaurants with Tom Colicchio wasn’t looking for something cute. “The reason Newburgh appealed to me is the same reason that some people don’t like it,” says Ortuzar, who moved here five years ago. “It’s a real city with city issues. It’s not a quaint little upstate town. It’s a beautiful place with a nice mix of old buildings and great architecture, but it’s also a real place where people are trying to make a go at it.”

We’re sitting in a common room of the latest outpost of the local coworking minichain Beahive in the Wireworks building, a refurbished and redeveloped spring factory that Ortuzar, along with Poughkeepsie developers AE Baxter and the design studio Mapos, have spent the past few years working on. The building, which also features apartments, artists’ studios, and an eventual retail space, opened just a few weeks ago. COVID may have slowed the project down, but many Newburgh development projects were able to get back up and running—with the proper precautions— rather quickly, since projects that had affordable housing components were allowed to get back to work sooner.

The Wireworks project keeps coming up when I ask people in Newburgh about what they consider an example of “good development.” Certainly the architectural details, the refinished wood tables made out of the tops of sewing machine tables that were found on site, the brick walls, the soaring ceilings, and the way the lateafternoon light makes the building seem to glow from the inside, has something to do with it. But Ortuzar takes his role as a citizen of Newburgh seriously. “I’m glad that I live here,” he says. “This is my community, so I’m not going to just develop for others. It’s for us who live here.”

For the city’s revival to stick, it needs more larger-scale projects like Wireworks, ones that will provide jobs and/or more affordable housing. That’s finally happening, says Joe Czajka, vice president of Pattern for Progress, a public policy think tank based in Newburgh. The Newburgh Food and Farm initiative received a $100,000 grant to build and maintain community gardens. Atlas Industries completed an eight-year project to transform a 55,000-square-foot warehouse located just across the street from Wireworks into Atlas Studios, and were hosting markets

caption tk

and readings before COVID struck. Thornwillow Press is building a makers’ village. Graft Cider is opening up a new cider tasting room, and Spirits Lab is operating a distillery on Ann Street in the ADS Warehouse space.

“I’m not into the idea of a place where you have to drive around just to live on a daily basis, so for me, Newburgh has everything,” says Gita Nandan, an architect who opened the ADS space with her husband, the sculptor Jens Veneman. They came to Newburgh from Brooklyn two years ago to find studio space for Veneman and promptly fell in love with the city. They also fell in love with the grey, T-shaped warehouse space on Ann Street, but knew that if they bought such a centrally located space, they’d have to use it as a means to contribute to the community.

Nandan shows me the parts of the building that are still in development: where the artists’ studios will be, the garden, the outside wall that will be turned into a movie screen. The courtyard already became an outdoor community hub last summer with such events as an art show honoring the 150th anniversary of Frederick Douglass coming to Newburgh to give a speech celebrating the 15th Amendment, and the couple is hoping to add pop-up retail and other outdoor, COVID-safe events this summer as well. “I like the way that people are being active and involved,” she says. “There are great people here.”

The New Narrative

Czajka and Dubois both say that the city is in a good position to come out of the pandemic stronger than ever, especially considering the increasing exodus of people leaving New York City after COVID, the city’s continued focus on making sure that new development has an affordable housing component, and the relief money coming to municipalities as part of the just passed $1.9 trillion stimulus bill. “It’s what our elected officials are supposed to do: represent the communities that are in distress, and get federal aid back to those communities,” says Czajka. “I think that’s very positive momentum.”

Dubois points to the just-completed $1.25 million deal to convert three historic side-byside buildings—a YMCA, a Masonic Lodge, and an American Legion hall—into a hotel, spa, and restaurant by the Sullivan County based Foster Supply Hospitality. It’s not just the size of the development that excites Dubois. “It’s from a Hudson Valley native,who really cares about being a good neighbor, working with the city, employing its residents and providing opportunities,” says Dubois. “It’s a unicorn of a development.”

The project, says Foster Supply Hospitality founder Sims Foster, whose family has lived in Sullivan County for over 100 years, won’t alter the historic architecture of the buildings. What it will change is the city’s story. “When

WHO WILL BE #1? VOTE NOW!

Lynn Hanson is one of the owners of Spirits Lab, a majority woman-owned distillery and tasting room in the ADS Warehouse at 105 Ann Street.

we’re open, we will bring over 25,000 people a year to the city of Newburgh,” Foster tells me. “We will give them a positive experience about Newburgh. And then those 25,000 people will go back to their proverbial water coolers and say ‘Hey I had a great weekend in Newburgh.’ There’s been a negative narrative about Newburgh for a long time. When you change that negative narrative into a positive narrative, like a hotel can do if they do it right, it can really help expedite a lot of good things for the people that live in that city.”

One doesn’t need to wait for these new projects to open to come and see the real Newburgh, and there’s plenty of reasons to visit even if you’re already familiar with Liberty Street. Newburgh’s ample bounty of taco stands is well known, but there’s also the clumps of Caribbean, Central American, and South American eateries that continue to pop up throughout the city like wildflowers. There’s its wild and wide-open views of the river and the Hudson Highlands, offering the ability to be in an urban environment that never lets one forget that you’re also in a changing natural landscape, with fog rolling in and clouds ascending the summits. And of course, there are the people of Newburgh itself, who have held the city together for decades. None of what is happening today would have been possible without them.

“The people here are struggling, but there are people who live here with really good ideas and a strong entrepreneurial spirit who want to improve their community,” says Czajka. “There needs to be programs, incentives, and technical assistance on how to create pathways to economic opportunity to eliminate generational poverty. And it can be done.”

This is Newburgh today, not in need of a single savior, but of anyone willing to dream big and fight hard. It’s worth remembering that the seeds of Newburgh’s regrowth were planted on Liberty Street over 200 years ago, at George Washington’s headquarters, now standing as a park that overlooks the valley. This is where Washington received what is now known as the Newburgh Letter, asking him to rule the new country as a king, and Washington said that America would have no king. Newburgh, and America, would be governed by the strength and the will and the vision of its people alone. It would rise and fall as one.

“When [our hotel is] open, we will bring over 25,000 people a year to the city of Newburgh. We will give them a positive experience about Newburgh. And then those 25,000 people will go back to their proverbial water coolers and say ‘Hey I had a great weekend in Newburgh.’

—Sims Foster Foster Supply Hospitality

Singular Discoveries

Recent Photographs by Andrew Moore Essay by Sparrow

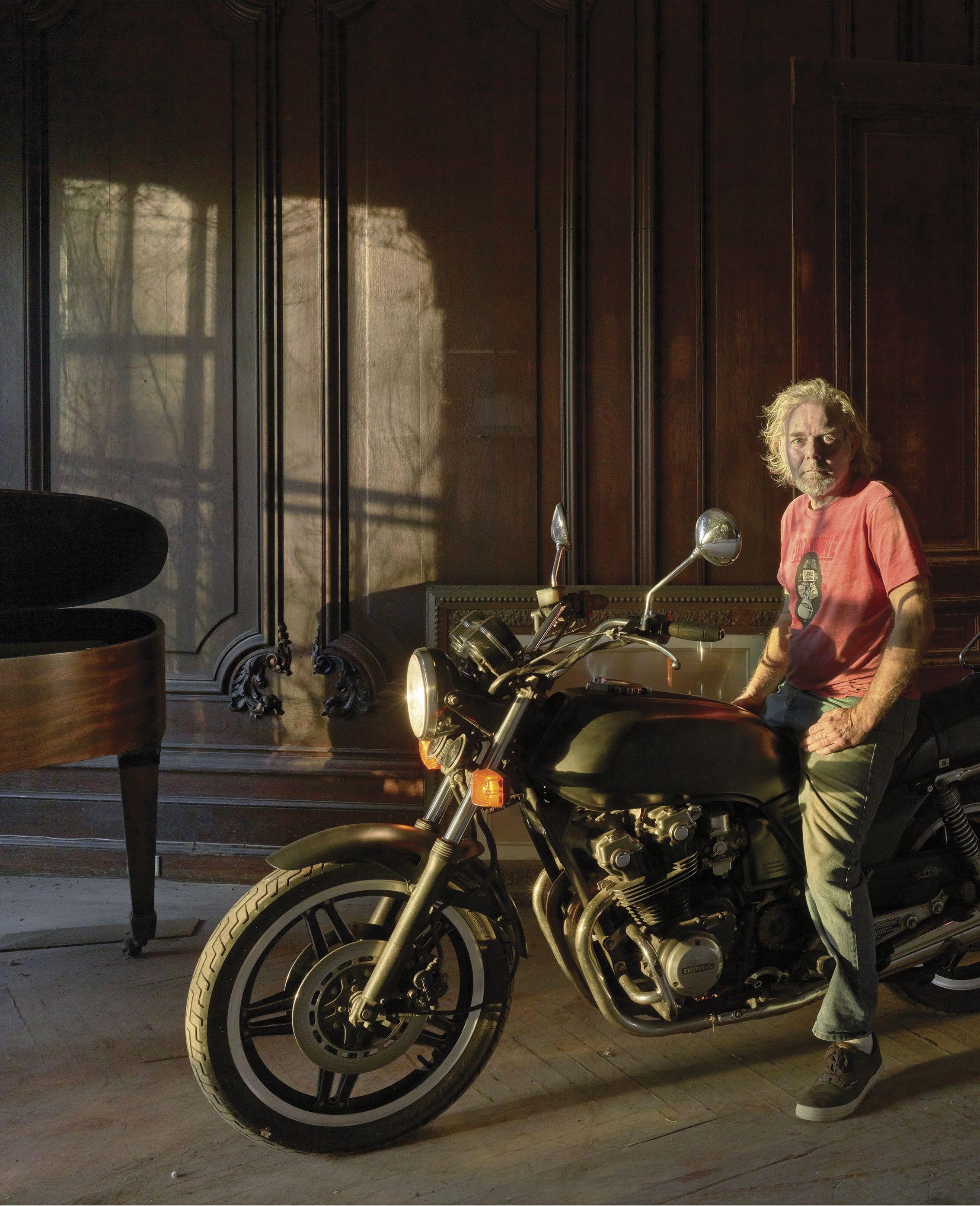

Erik at Rock Ledge Erik Mermogen, an artist and motorcycle enthusiast, is the caretaker of Rock Ledge, a turn of the century Italianate manor house in Rhinebeck, where he stores his bikes. He’s sitting on one of his favorites, a 1979-82 Honda CB750F which he built from parts.

Agambler rolls the dice. A photographer picks up a camera and walks out into the street. Both of them confront the agonies of chance, of luck, of fate. Both can win big or go down in flames. The danger of being an artist or a gambler is that you can utterly lose faith in yourself.

Andrew Moore has succeeded in the uncertain world of photography. His work is included in dozens of museums, including the Smithsonian and the Whitney. His photos have appeared in the New Yorker, National Geographic, the New York Times Magazine, the Paris Review, and many other journals. He’s published eight books of photos.

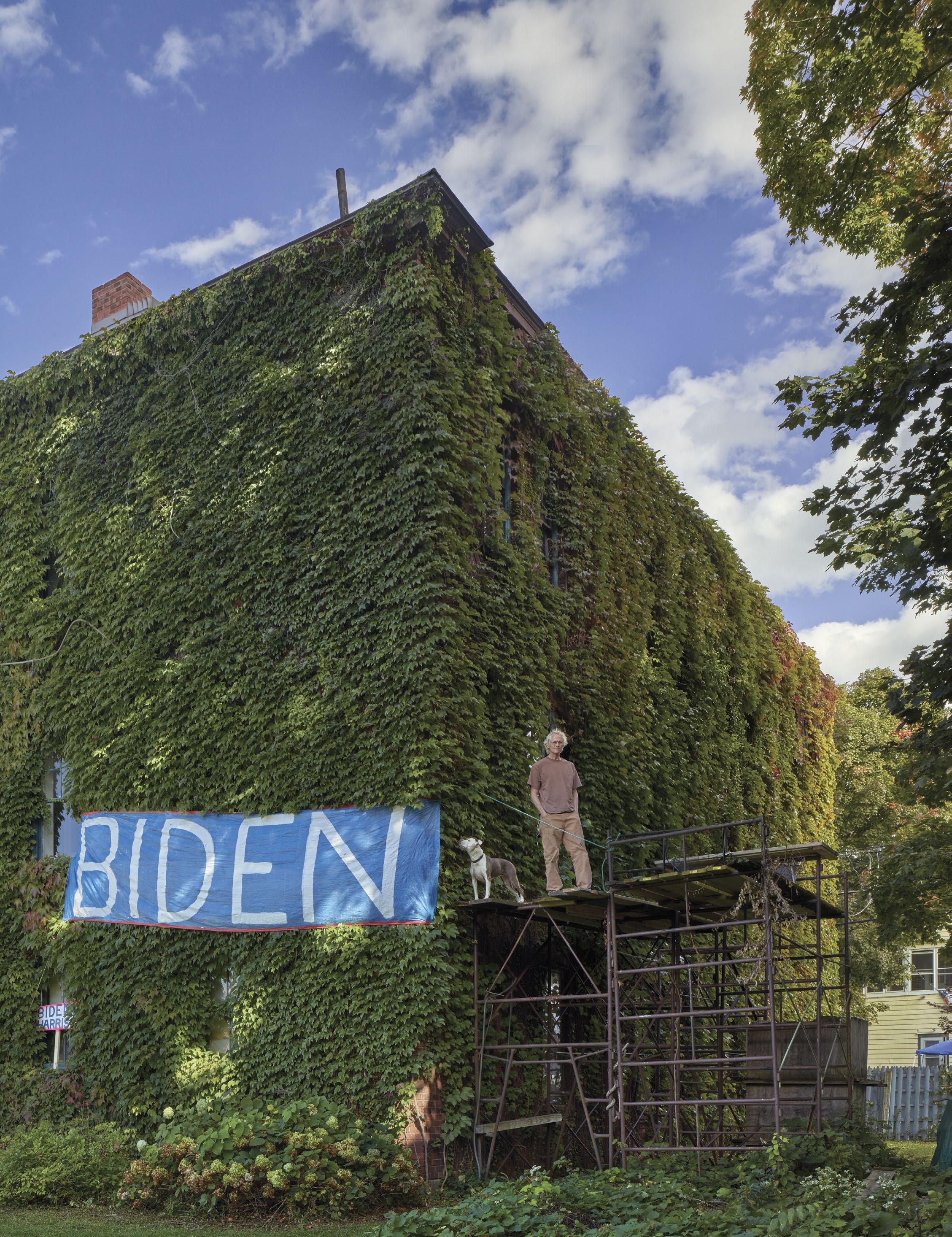

Hank at Dougrey’s Hall Hank Murta, a well-known glass artist, purchased Dougrey’s Hall in Lansingburgh as a home and studio in 1988. The hall was originally founded as an Irish social club by the Dougrey family who owned one of many local breweries, of which in Troy at the time there were 17, a number said to equal the number of operating foundries. The building was completed in 1900, built in the New England grange style, with stables on the ground floor, a hay loft and grooms quarters on the second, and a clear span dance and lecture hall on the third floor.

Yet at first one might mistake his pictures for snapshots. Hank at Dougrey’s Hall shows a man and his dog on scaffolding next to a building in Troy with a huge “Biden” banner. The handmade sign is reminiscent of a castaway on a desert island writing “HELP!” in giant letters, for a stray airplane to see. Many of us felt this sort of desperation during the last election. The rickety wooden platform emphasizes the precariousness of Hank’s plight. (In fact, this platform is a homemade balcony. Hank is an artist who has lived in this house— which was once an Irish social club—for 25 years.)

Moore moved to the Hudson Valley two years ago, and is enthusiastic about exploring the area, the same way he has investigated Russia and Abu Dhabi in photographic essays. The images in this spread were all taken in the last six months. “My assistant and I, we’re kind of like private investigators,” Moore explains. “We go out, knock on doors; there’s a lot of dead ends. You gotta check out all the leads.”

When you first see Erik at Rock Ledge, you think, “What’s a motorcycle doing in a living room—next to a grand piano?” The juxtaposition seems impossible, like a ship in a bottle. But when you look closely, you see that the doorway is quite large, and in fact two other motorbikes are protruding from rooms down the hall.

Another question: Did Moore set up the shot? I am in the enviable position, as an art critic, of being able to ask the artist the backstory, but a visitor to an art gallery seeing these pictures can’t know. Yet there’s a certain sincerity in Moore’s photographs. They don’t seem to be constructed, like ads for Smirnoff vodka.

Above Dr. Nohoo in the Rain This former Troy paint factory, which will soon get a new roof, is being re-purposed into artists’ studios by Dr. Brian McCandless, who along with his partners, hope to replace the kind of live-work spaces that have been lost in recent years to tax-incentivized housing construction. Having kept a sculpture studio in this neighborhood for decades, McCandless is the leading advocate for local artists in this part of Troy that he calls Nohoo, (North of Hoosick Street), an area that for years was filled with zombie buildings and absentee landlords. McCandless sees himself a part of a social experiment in which investors put their resources (both financial and personal) into the places where they reside and work.

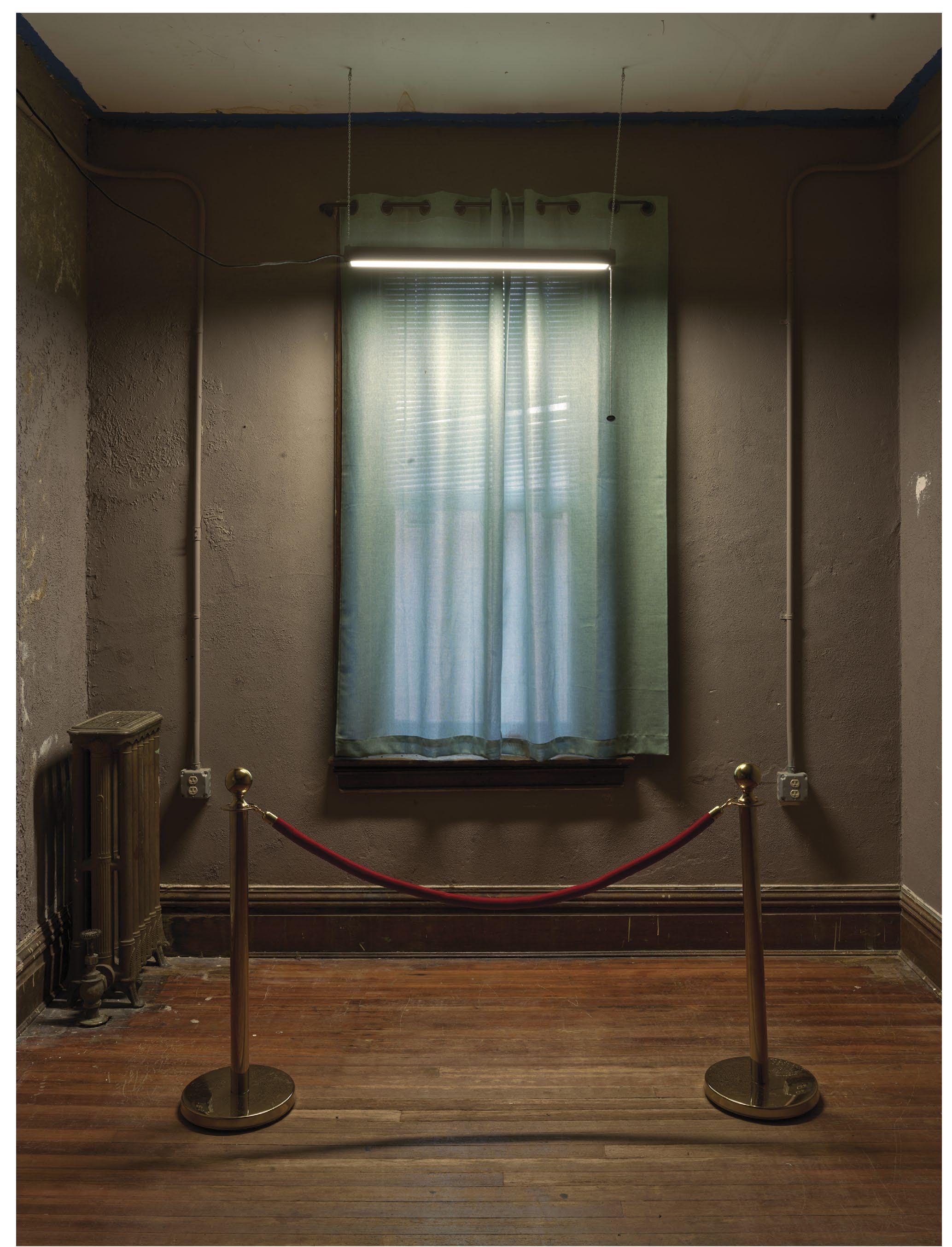

Opposite Forest East Room The John Paine Mansion, otherwise known as The Castle, housed the brothers of the Pi Kappa Phi Fraternity, Alpha Tau Chapter at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute for 50 years. The mansion also served as a location for Martin Scorsese’s 1993 film, The Age of Innocence.

In fact, Rock Ledge is a mansion that became a rehab center for Daytop Village, and is presently unused. Erik is the caretaker, and stores his motorcycles there. He’s also responsible for the sign “Challenge Your Fears” above the doorway. On a wall at the rear of the hallway are some Daytop Village slogans. (Moore’s photographs are intended to be printed in large format, where telling details become easily visible.)

Moore was very forthcoming in his conversation with me, but there was one secret he wouldn’t reveal: the story behind Forest East Room, an image of a whitecurtained window behind a velvet rope. (The artist privately calls it “The Museum of Nothing.”)

Moore takes a great deal of care with his titles, incidentally. He doesn’t want to reveal too much, and transform the photos into journalism. He always includes the location and year, however, to give some historical context.

One of Moore’s subgenres is portraits without people. Jane’s Suitcase depicts a bed with a traveling case and a book resting on it. Of the three pillows, only one shows the impression of a head. We sense Jane’s presence—even her regrets— without seeing her. Sicilian Defense at Tivoli Mike’s is a close-up of an outdoor chessboard, set up for a game, with leaves strewn across it. Two moves have been made, one on each side. (The “Sicilian Defense” is a famous chess opening.) Who were these players who abandoned their game after a single move, allowing autumn leaves to decorate the board? Did they suddenly decide to make love? Was there a family emergency? Did they collectively realize they hate chess?

When I was a kid, there was a cartoon character named Mr. Mum who appeared daily in the New York Post. He was a bald, bespectacled, middle-aged gentleman who walked through life silently observing. Mr. Mum would encounter outlandish scenes: two armed robbers robbing each other, a man at a lost and found retrieving his own head. He never spoke, but he looked bewildered. Moore’s photographs remind me of the singular discoveries of Mr. Mum.