9 minute read

Excerpt

by Chronogram

Reservoir Year

A Walker’s Book of Days

Advertisement

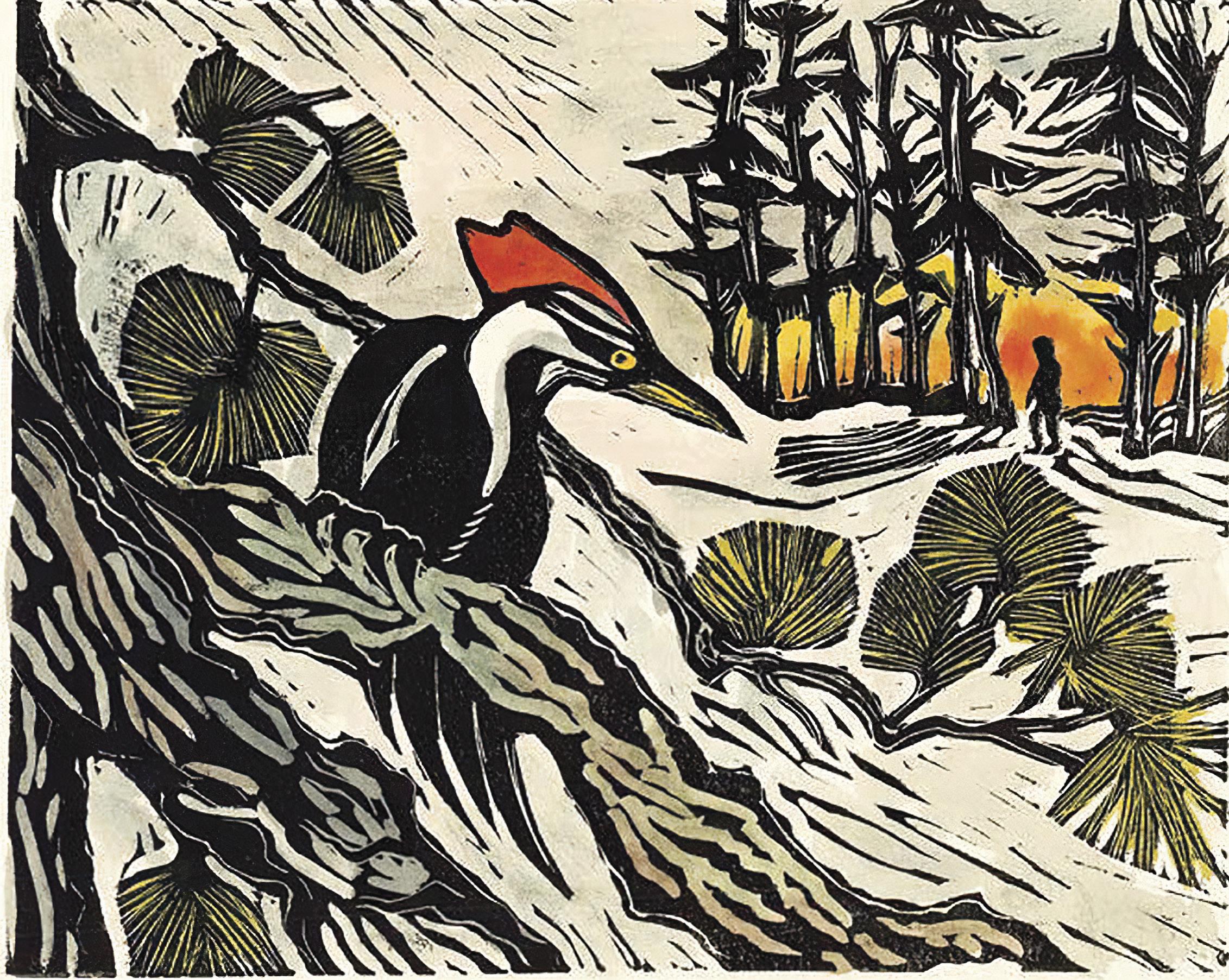

By Nina Shengold Illustration by Carol Zaloom

The following is an excerpt from Reservoir Year: A Walker’s Book of Days by Nina Shengold, which is being published this month by Syracuse University Press. Shengold was books editor at Chronogram for over a decade. This is her third book. Numerous author events are planned for August and September; visit ninashengold.com for details.

Ilive in the foothills of the Catskills, four miles from the glorious Ashokan Reservoir. For a year, I walked by its side every day, in all kinds of weather, from predawn to starlight.

My usual path is a former roadbed on top of the reservoir’s main dam. There’s a small parking lot near the village of Olivebridge rimmed by wildflowers, hardwoods, and pines. You pass through a row of traffic barrier columns and take a few strides to the edge of the trees, and the world opens up: a panoramic vista of water, mountains, and sky. People stop in their tracks and gasp. I once heard an awestruck child cry out, “Is that the ocean? Mom! What is this place??”

It’s a good question. I spent a year trying to answer it, day after day after day. I was poised to turn sixty, a birthday that can’t help but rattle the ribcage. My daughter Maya was at college in Vermont and I missed her bright energy daily; my parents were dwindling into their nineties. And my dog had died.

Chris was my first dog, a not-so-golden retriever mix we adopted when Maya was a first grader with puppy lust. Having a dog ensures that you spend time outdoors every day, however you’re feeling, whatever the weather gets up to. And that lifts your spirits, whether you like it or not. It’s not just the endorphins from exercise, but the subtle pleasures of noticing seasonal changes. What new flower has opened today? Look at the frost on that leaf. Are the robins back yet? It’s a daily unfolding of wonder, a pause in a day that is otherwise crowded with too much to do.

For 13 years, we took the same walk every day, at first circling the block in a three-mile loop, later a mile to the end of the road and back, and finally a stop-and-go shuffle on a flat stretch of road in front of my house. I couldn’t bear to walk my block dogless, so I stopped walking. Of course I gained weight, and felt trapped and depressed, but months passed before I got a clue.

It took two of my brother David’s friends, visiting from Saint Petersburg, Russia, to open my eyes. When I asked what they’d enjoyed most on their trip to America, Sergei didn’t hesitate. The Ashokan Reservoir, where David had taken them that afternoon. Such magnificence!

I was flooded with shame. The Ashokan is practically in my backyard, and I hadn’t walked there for months. Twelve miles long and a mile across, divided into unequal halves by a multiarched weir bridge across its wasp waist, the reservoir is an ideal reflecting pool for the Catskill High Peaks. The vast expanse of water allows a long-distance view of a densely forested range that could otherwise be seen only from above. The Ashokan is a different kind of gorgeous in every season, in every kind of weather and light. But its beauty is built on a paradox. Beneath its great bowl lie the ruins of 12 communities uprooted by the city of New York in an arrogant turn-of-the-century land grab that impounded the Esopus Creek to bring mountain water to an urban island that had outgrown its water supply.

Between 1907 and 1916, more than two thousand people were evicted from land their families had farmed for generations. Trees were chopped down, stumps grubbed, buildings burned, cemeteries exhumed. African American and immigrant laborers died in labor camp brawls and industrial accidents. When the thousand-foot dam was complete and the water began to rise, it flooded a valley once filled with farm fields and country stores, gristmills and blacksmith shops, bluestone quarries and railroad tracks, churches and graveyards. Though this grim history is detailed in such books as Bob Steuding’s The Last of the Handmade Dams and Diane Galusha’s Liquid Assets: A History of New York City’s Water System, most of the people who visit the scenic location have little idea of what came before.

Along New York State Routes 28 and 28A, the two roads that encircle the reservoir, a series of brown highway department signs commemorates the Former Sites of Ashokan, Ashton, Boiceville, Brodhead, Brown’s Station, Glenford, Olive, Olive Bridge, Shokan, Stony Hollow, West Hurley, West Shokan. The names toll like church bells, bemoaning a past so completely erased that even official signs disagree on exactly how many hamlets and towns were destroyed or uprooted to higher ground.

The name “Ashokan” comes from an Algonkian word variously translated as “place of many fish” and “to cross the creek” (another erasure of history; the Esopus Indians were displaced by European colonists long before their descendants were displaced by the dam). Jay Ungar’s haunting fiddle tune “Ashokan Farewell” was featured in Ken Burns’s Civil War documentary series and widely recorded. Its plaintive blend of uplift and lament is an ideal soundtrack for this place of great natural beauty and manmade sorrow. It’s a landscape that gets in your bones.

After Sergei pronounced the Ashokan “magnificent,” I took a walk there one September evening, went home, and wrote about it. Then I did it again. I’ve always been moved by art that revisits the same subject again and again over time: Monet’s water lilies and studies of Rouen Cathedral, Nicholas Nixon’s photo series of four sisters aging. Could I do that with words?

More to the point, could I do it at all? What about weather, and travel, and getting sick? What about willpower?

I am not a person of discipline. New Year’s resolutions head south before Groundhog Day; diets disintegrate; writing regimens of so many words per day dead-end the first time I don’t make my quota. As soon as I made the decision to walk every day for a year, I felt a familiar shiver of doom. But the thought of it wouldn’t let go. Reluctant or eager, I had to keep going. I got obsessed.

My intent was to write about what I observed—to be camera, not subject—but my daily walks conjured all the back roads that had brought me to this one. As a kid growing up in an orderly New Jersey suburb, my favorite book was Jean Craighead George’s My Side of the Mountain, about a teenage boy who lives off the land in the Catskills, sleeping inside a hollow tree and training a peregrine falcon to hunt. I wanted to be Sam Gribley, girl version. I hungered for life in the wild.

At 22, I took a radical swerve from my urban career goals and spent a year living out of a backpack with no fixed plan, wandering through the Pacific Northwest and north to Alaska. In my thirties, I bought an old farmhouse in the Catskills and became a single mother, forging a warming fire of creative connections with my new community.

Who would I be at age 60? I was going to find out, come hell or high water.

When I told people what I was doing, their first response was nearly always “Are you taking pictures?” It was often asked anxiously, as if the experience wouldn’t exist if it weren’t recorded in pixels.

“Nope,” I would tell them. “I’m doing it old school.” I didn’t even take paper and pen on my walks; I wanted to train myself to experience things with my senses and carry them back in my mind, to hunt and gather unarmed. There’s a kind of surrender in this, trusting the sieve of memory to strain wheat from chaff. In a world where we stare at computer screens for hours every day and carry our cell phones and digital cameras wherever we go, it’s good to remember that we are recording devices: our eyes, ears, and noses, our tongues and our skin take things in, and it’s good to be fully awake when it happens. When a bald eagle flies over your head, you don’t want to miss it because you’re hunched over your notebook.

My daily walks ranged from a quick half mile out and back to five miles or more. Sometimes I

went off road, exploring the many access points for fishing and hunting along the reservoir’s forty-four miles of shoreline. (Since I wasn’t fishing or hunting, this wasn’t exactly approved “Recreational Use,” but I improvised.)

I walked sometimes with family and friends, more often alone. As a freelance writer-editorteacher, I could start or end my workday at the Ashokan, or take a lunch break between marathon sits at my desk. I could—and did—go out walking after midnight. From September 2015 to September 2016, I structured my comings and goings around reservoir walks, rerouting both day-to-day errands and overnight trips. If I had to travel, I stopped at the Ashokan on my way to or from the train station or airport. I commuted daily from a residential writing workshop across the Hudson and irritated my relatives by driving home and back—a round trip of more than five hundred miles—midway through a family reunion.

This is how an obsession takes hold. It’s not a decision to strap on the harness, but a slowdawning realization that you’ve got a bit between your teeth and an unshakable weight on your back spurring you on. I had no way to predict what would happen during my reservoir year. I only knew where I had to be to find out.

It wasn’t a wilderness retreat on some remote mountaintop, or even Thoreau’s Walden Pond (down the railroad track from his parents’ house, where the apostle of solitude often ate lunch). The Ashokan walkway—what locals call “walking the dam”—is a paved former road frequented by hikers, exercise walkers, runners, bicyclists, rollerbladers, skateboarders, tourists with iPhones, and wildlife photographers staking out calendar shots of the resident eagles. I’m far from the only regular, and the human ecology interested me as much as the minks and mergansers. If you live nearby and frequent “the res,” you may find yourself (or some version thereof; certain names and identifying details have been changed) in this book. My apologies for any misguided assumptions.

What I set out to do was go back to the same place again and again and find something new every time, to check in with the daily rhythms and cycles of nature, and sometimes to glimpse the sublime.