22 minute read

Legal Weed Is Coming

CANNABIS AND THE EMPIRE STATE

By Amadeus Finlay

Advertisement

Persistence pays off in politics, and as Governor Cuomo prepares to present a recreational cannabis bill in the upcoming legislative session for the third time in his tenure, the feeling in Albany is that it will happen this time around.

Approximately 1.3 million people across the state consume THC-based products (the stuff that gets you high—think Cheech and Chong; big, stinky buds). A poll conducted by Spectrum News of Albany and IPSOS Global in October found that 61 percent of respondents favored the legalization of recreational cannabis. In 2018, residents of New York City consumed an estimated 77 tons of cannabis flower—more than any other city on the planet according to a 2018 study from Seedo.

The state’s medical cannabis program, launched in 2014, has 133,362 “certified patients,” with over 3,000 medical practitioners across New York registered to prescribe medical cannabis (albeit in some derivative form, not flower). Hemp is also big business, with approximately 18,000 acres of the crop being produced by more than 400 licensed growers. But there is a gap. While New York decriminalized recreational marijuana use in 2019—possession of small amounts of the drug are punished with fines rather than jail time—it’s still not legal.

Recreational Cannabis: The View from Albany

The financial downturn caused by the pandemic will cost the state a shortfall of almost $63 billion over the next four years, and recreational cannabis would generate an estimated $300 million in additional annual tax revenue—an attractive argument for legalization. (Even if lawmakers legalized marijuana tomorrow, however, it would be years before revenue from the marijuana industry hit the $300 million level.) Consumer demand remains strong, and with neighboring Massachusetts selling legal weed and New Jersey voters approving recreational marijuana at the polls, New York is late to join the party. Add a Democrat supermajority in both chambers, and the deal seems all but done.

But not everyone at the Capitol is convinced. Senator Pete Harckham (D) serves as Chairman of the Committee on Alcoholism and Substance Abuse and co-chair of the Joint Senate Task Force on Opioids, Addiction & Overdose Prevention, and feels the proposed legislation does not go far enough to address substance abuse, treatment, and education. “The governor’s bill is just treated as general tax revenue that goes in the general fund,” says Harckham, whose district includes parts of Dutchess, Putnam, and Westchester counties. “We desperately need the money to go toward substance abuse disorder. New York State is woefully underfunded, and during the pandemic the overdose rate has doubled. Treatment providers are hanging on by a thread. This is a real crisis.”

But Harckham is not opposed to recreational cannabis. Instead, he points to an alternative bill, S1527B sponsored by Assembly Majority Leader Crystal Peoples-Stokes (D) and Senator Liz Krueger (D), that directs 25 percent of recreational cannabis revenue toward substance abuse, treatment, and education.

“It’s all covered,” continues Harckham. “There is money in the bill for local police who don’t have the resources to address DUIs, money for school districts to address risky behavior, and provisions for opt-out and local zoning.”

Another advocate is Melissa Moore, state director of the Drug Policy Alliance. “We solidly support the Krueger bill because it learns lessons. From an advocacy perspective, the areas that stand out still with the Governor’s bill are what we would do with cannabis tax toward social equity and diversity components.”

However it shakes out in Albany, change is

most certainly needed. Under current legislation, cannabis growers in New York State (whether medical or hemp producers) are not permitted to sell flower, meaning consumers and patients can only attain cannabis byproducts rather than organic plant material.

“It is a public policy failure,” says Jason Minard, attorney to Hempire State Growers. “Vapes, which are full of toxins, are in, while natural flower, which farmers can grow and quality control, is out. The ban on flower products has been a major blow to Governor Cuomo’s promise to protect the farmer. It is an injustice and doesn’t add up.”

The New York Small Farm Alliance of Cannabis Growers and Supporters (NY Small Farma) is a nonprofit founded to “ensure social and environmental justice for cannabis in New York State,” and as vice president Donna Burns, says, “the ability of ordinary people to enter this industry must be recognized. Farm co-ops and sustainability must be embraced as part of the solution. If industrial grow warehouses become the norm, we could see the state’s progressive climate goals nullified. The tax scheme needs to expressly incentivize outdoor growing. Leaders should think big and enact small.”

The Medical Opinion

Cannabis remains under close scientific scrutiny, having only been made available for legal study within recent years. But a consensus on patient use is already forming within the medical community, and it is overwhelmingly positive. Dr. Richard Carlton, a specialist in integrative psychiatry based in Port Washington, has been practicing medicine in New York for over 20 years, and began prescribing medical cannabis for his patients in 2013. Inspired by his successes, Carlton has studied the plant ever since. “Cannabis is the most effective pain reliever, bar opioids, on the planet,” states Carlton. “But unlike opioids, you cannot overdose on cannabis because there are no receptors in the respiratory and cardiac system of the brain.”

Carlton continues: “There are two main cannabis receptors in the brain—and I am oversimplifying—CB1 and CB2. These cannabinoid receptors [part of the endocannabinoid system that regulates and balances processes such as immune response, metabolism, and communication between cells] are hit by the cannabis in the plant.”

“Cannabis receptors are presynaptic, meaning they transmit signals in the brain,” details Carlton. “When pain is overfiring, postsynaptic neurons are bombarded with pain messages. Cannabinoids hit the presynaptic neuron, causing them to blunt the pain.”

Dr. Rachel Kramer, an oncologist at Mt. Sinai Hospital and Lenox Hill Hospital in Manhattan, echoes Carlton’s convictions, prescribing both THC and CBD as solutions for pain relief, appetite stimulation, and nausea management. “Narcotics and regular antinausea medications are limited because they cause constipation,” explains Kramer, “and chemo patients are frequently constipated due to the side effects of their treatment. Medical marijuana is a way of managing the nausea, appetite, and pain.”

Kramer also reassures her patients against historic misconceptions. “There is zero medical basis to suggest that cannabis is a gateway drug. Those who prescribe Percocet— there is no greater gateway drug.” Carlton agrees: “It’s why oxycodone makers are so opposed to cannabis and fund groups who are opposed to it. Cannabis is the exit to serious addiction; it gets them off the opioid.”

This page, scenes from Hempire State Growers' Hudson Valley farm: Amy Hepworth, lead farmer, directing farm crew; air drying freshly harvested hemp. Hempire is poised to enter the recreational cannabis market if marijuana is leaglized in New York.

The Canna Provisions dispensary in Holyoke, Massachusetts. If recreational marijuana is legalized in New York, consumers might be able to shop in weed in swank boutiques like this one. Photo by Melissa Ostrow

—Melissa Moore, Drug Policy Alliance

However, there are institutional limitations to who can benefit from the medicine. One of Kramer’s patients was a police officer, yet he was ineligible for a medical cannabis prescription due to the laws surrounding his employment. “If the plant didn’t have THC,” explains Carlton, “it would be the most widely prescribed herbal medication. If it were just the other cannabinoids and terpenes, it would be the most widely used drug on the planet. It has been proven in scores of medical conditions—ALS, migraines, Crohn’s disease, arthritis, cancer, the list goes on.”

The People’s Voice

There is more to cannabis and its social impact than bureaucratic posturing and the focusing of microscopes. For over 100 years, the plant has been used as a tool of racial oppression, and the legacy of that mistreatment will take more to unravel than the signing of a bill.

In June 2017, Assembly Member PeoplesStokes (D) reported that, “Black people are almost four times more likely to be arrested for pot. This criminal record follows them and they’re essentially locked into a second-class status for life.”

Moore of the Drug Policy Alliance agrees. “It isn’t enough to simply turn the page. There have been generational socioeconomic impacts as a result of marijuana prohibition and targeted policing, disproportionately in Black communities.”

“People may not be aware how much cannabis, race, and drug policy have wound their way around each other. Cannabis possession is the second most stated reason for the preponderance of what immigration officials are using as basis to deport people and destroy families.”

Moore relates that prohibition was never founded on pharmacology, but through a desire to control and criminalize populations. “In the nightclubs of the 1920s, white people were freely mixing with people of color. It is then you see a ramping up of legalization campaigns as a way of keeping these populations apart.”

“Demonization of this ancient and useful crop was very misguided,” says Burns. “This plant has been part of human history for thousands of years. As the 100-year prohibition lifts, we need to create a sustainable path for those who have been harmed by the war on drugs and practices of exclusion.”

The path toward recreational cannabis in New York has laid its first stones, its pioneers taking their first steps on what will be a journey of endurance. A stage, if it can be called that, has been set, and the directions from those on the wings call for small, community practices founded in quality, sustainability, and local development. Governor Cuomo knows what needs to be done, the voices around him are loud, clear, and uncompromising: New York could be a model for the rest of the world.

Strong at Heart

POUGHKEEPSIE

By Jamie Larson Photos by David McIntyre

This time last year, Poughkeepsie was at an inflection point. Just before the COVID-19 pandemic descended, the city was buzzing with development, new businesses, and growth. The community was also bolstered by the civic and social support of a cadre of dynamic nonprofits, and it seemed that a long period of economic struggle was at last subsiding. Then, you know, COVID. Progress in Poughkeepsie, however, has not been derailed, thanks to the people who have pushed too long and hard to let the city backslide. The past year has been emotional and exhausting, but Poughkeepsie’s stakeholders have found a way to fight through. They just work harder.

City of Healers

Poughkeepsie is a hospital town, with Vassar Brothers Medical Center (VBMC) in its center and Mid-Hudson Hospital just outside the city limits. The city is slung with banners honoring healthcare workers and a popular statue of a masked nurse standing resolute, sculpted by artist Nestor Madalengoitia, guarded the entrance of VBMC, before relocating to the Dutchess County Office Building. “I think, as a community, we feel comforted by the fact we have two amazing hospitals centered in our community,” says Poughkeepsie Mayor Rob Rolison. “On a personal level, I’m concerned for healthcare workers and the stress they’re under. I came down with COVID-19 the Monday before Thanksgiving. My experience was certainly not as bad as others. I was very lucky. It showed me the fragility of life. We need to take the time to thank one another.”

In the midst of the pandemic, and after years of construction, on January 9, VBMC opened their massive new Patient Pavilion building complex. The $500-million project brings new space and resources to the hospital at a vital time as COVID case numbers continue to rise. “It’s an amazing facility with all private rooms, so that immediately addresses needs for isolation and capacity,” said Dr. William Begg, vice president of medical affairs at VBMC. “The new

Ira Lee, owner of Twisted Soul, a fusion restaurant located near Vassar College on Raymond Avenue. Twisted Soul is only offering pick-up service during the pandemic.

Opposite, top: A view of the Mount Carmel neighborhood and the Mid-Hudson Bridge in the distance from the eastern end of the Walkway Over the Hudson.

Middle: The Vassar College campus in Poughkeepsie. For the spring semester, Vassar will pursue its “island” model for students once they begin returning this month. Once on campus, students are expected to remain on campus for the duration of the semester.

Bottom: God’s Grace Too!! is located on a stretch of Main Street with many Mexican, Caribbean, and soul food restaurants.

patient pavilion just adds an advanced location that will help us provide the level of healthcare our community deserves.”

Begg says the staff at VBMC have faced many challenges over the past year with consummate professionalism and the community of the greater Poughkeepsie area has been continually supportive. “When the pandemic began, they came out in droves, donating food, masks—even coming by the medical center in impromptu drive-by salutes to our healthcare workers. It’s an incredible feeling to get that kind of support, and it really energized all of us,” Begg said. “I feel like we’re closer in many ways. Despite many challenges, we’ve developed relationships with local public officials and we’ve ventured out into the community with educational seminars. We’ve done two virtual town halls about COVID-19 featuring members of our medical staff as panelists, and we plan to do more this year, beginning with some education about vaccines.”

COVID Curbs a Comeback

Major economic development projects like the hospital expansion, the creation of a hotel and conference center on the Vassar College campus, Queen City Lofts, One Dutchess, Poughkeepsie Landing, and others saw their build-outs slowed but not stopped by COVID restrictions. In January, the Academy mixeduse development got underway in earnest. That project will establish a coworking space, coffee shop, food hall, brewery, fresh foods market, teaching kitchen, and event space, with apartments on the upper floors on Academy Street. The continuation of these projects signals investor confidence in Poughkeepsie, in spite of current circumstances.

Other hospitality-based projects that opened in the beginning of last year have struggled, however. In early 2020, a new go-kart and arcade facility, RPM, opened at the Galleria Mall. Jim and Gina Sullivan, developers of the 40 Cannon complex, opened the Revel 32 nightclub and events space. Legendary sandwich shop Rossi’s Deli opened a second location in the Eastdale Village development. The brewing industry was also roaring with the success Mill House Brewing Company, Blue Collar Brewery, and Plan Bee Farm Brewery, and the recently opened Zeus Brewing Company.

Most businesses in the city continue to limp along, waiting for more Payroll Protection Plan stimulus from the government, but some, like the Bowtie Cinema project, are on hold, as the state of the movie theater industry is dire. Restaurants are in a particularly mercurial quagmire, with those who have robust takeout options doing okay while fine dining establishments that are more experiential, like Brasserie 292, are losing more and more footing by the day. Brasserie owner and chef Charles Fells is frustrated by the way the narrative around COVID’s spread has focused so much on restaurants.

“It seems like we’ve pigeonholed restaurants as the source of COVID, and that’s really sad,” says Fells. “No one in our business wants to get people sick. I don’t know how people think it’s so much worse than the grocery store. Ninety percent of our menu doesn’t travel well. We are still doing

Cottage Street in Poughkeepsie is home to a number of manufacturing businesses, like 4th State Metals, a fabrication facility that works with architects and artists. Left to right: Ben Kane, Isaac Zal, Blake Burba, Dave Markusen Weiss, and Lauren Fix.

limited-capacity seating with spacing. We put up Plexiglas around the booths and got a whole new HVAC system. We’ve followed every guideline. It’s nuts.”

Fells says if there is another total shutdown, without Payroll Protection or substantial government stimulus, he won’t be able to keep the restaurant open. He added that he’s already done everything possible to stay open and keep his employees paid, including remortgaging his house. “Aid gets tied up in Washington because it’s too political. It’s not about what’s best for the country, it’s about what’s best for political careers,” Fells says. “If the shutdown and regulations were handled federally from the beginning I wouldn’t be in this position.”

A Housing Boom with Pros and Cons

While existing Poughkeepsie businesses are struggling, it is proving to be a good time to start a new venture in the city, as entrepreneurs see a post-pandemic clientele eager to get back out and socialize.

Industrial and commercial real estate agent Don Minichino of Houlihan Lawrence has years of professional experience in economic development and says he still approaches his work from that perspective. Minichino says that the hot residential real estate—fueled by New York City exiles—is the basis for future opportunities on the commercial front.

“I live in downtown Poughkeepsie and it’s where my heart is,” he says. “There are two sides to the story right now. I’m seeing food businesses sell to recoup some value back from all their hard work. On the other side of the coin, I have restaurant spaces I have been able to lease to people who want to rehab them now, for new eateries when this is over. There are a lot of people sitting at home looking to turn their dreams into reality.”

The robust real estate market, however, means higher rents and fewer options for the housing insecure. Lack of work and opportunities has only seen that community’s numbers grow. Along with managing scores of low-income housing units and a portfolio of community aid programs, Hudson River Housing runs the only homeless shelter in Dutchess County. Unsurprisingly, the pandemic has made that difficult endeavor even more challenging.

“We didn’t want to be in a position to have to turn anyone away, and we realized our existing facility was not the best site,” says Hudson River Housing Executive Director Crista Hines, of the early days of COVID-19. The county made a vacant facility on the grounds of the Dutchess County Jail available, and while the organization was initially concerned about the connotations and image the location would send to their clientele, Hines says it has been a major upgrade for the folks they serve. Hygiene and food service accommodations are greatly improved and capacity increased so the organization could safely shelter 150 people. Sadly, the larger capacity has been needed as they are regularly housing 110 individuals a night, up from 60 this time last year.

“The challenges our clients are facing have been exacerbated by the pandemic,” Hines says. “Those with serious drug issues have had a more difficult time accessing counseling. There have been more overdoses than we have seen in forever. Services are available, but they are harder to access remotely.”

Hudson River Housing also does a lot for those struggling to keep up with the cost of their apartments and homes. In April, the organization opened 78 new low-income housing units in Poughkeepsie and are working every day to develop more in a city currently with a one-percent vacancy rate. While the work they’ve accomplished has been a great value for the community they serve, looming is the ever-present, growing need. Hines says they receive over 100 applications for housing a month. “We were in a housing crisis before the pandemic and this has pushed it over the edge. Any available housing is getting gobbled up,” Hines says. “I think things are going okay, but we are kind of waiting for the other shoe to drop with the economic impact of COVID.”

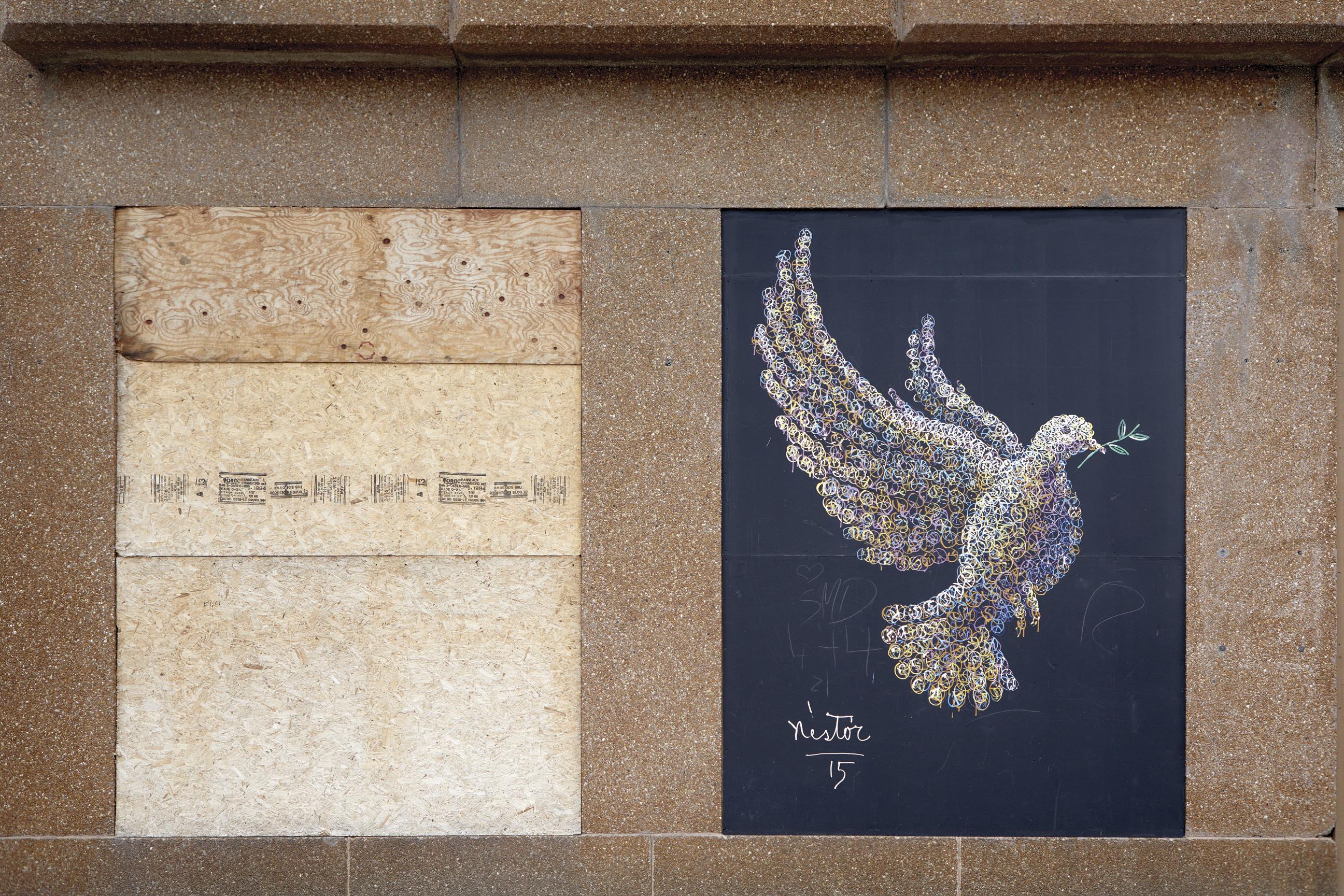

Carmen is a self-described “panhandler” who is so well known for sitting at the corner of Main and Catherine Streets that the mayor had a sign put up declaring the spot to be “Carmen’s Corner.” Opposite: Top: The Dove, a mural by Nestor Madalengoitia on Main Street. Bottom: Queen City 15 is a member-run art gallery on Main Street. The sculpture in the window is Gnome Lisa by Lisa Winika.

The situation has driven the fair market value of a one-bedroom apartment in Poughkeepsie to an untenable $1,200 a month, she adds. To combat this, Hudson River Housing is working on increasing their rent relief programs and those in need are encouraged to visit the organization’s website to learn more about that and many other programs servicing vulnerable citizens.

A Republican’s Pride for a Protest and the Shame of a Coup

Through the summer, Poughkeepsie also became a regional epicenter for protests demanding remedy for racial inequality. Thousands marched peacefully through the city in June, lending their voices to the national outrage over the shooting of George Floyd and all people of color unfairly and unequally targeted, harassed, and killed by police.

Black Lives Matter rallies focused the public lens on the city’s own police reform efforts. Mayor Rolison says the Poughkeepsie Police Department has embraced procedural justice reform and implicit bias training for their officers. “We understand how important this is and we know we have more to do,” says Rolison.

In contrast to the positive power of the BLM protests, I happened to speak with the mayor less than 48 hours after Trump extremists stormed the Capitol building in Washington on January 6. The deadly, shambolic coup attempt was still very much front of mind and had Rolison thinking about the local impact of inflammatory partisanship. “This event at the Capitol was four years in the making and shame on [President Trump] for keeping it going and having this ill-advised rally. When you belittle people and call them names, it accomplishes nothing. We’ve been way beyond the breaking point for a while,” Rolison says, emotion rising in his usually even-toned voice. “Unfortunately, with the dysfunction in Washington, it trickles down to the local level and the partisanship becomes normalized. I’m a Republican, elected mayor twice in a Democratic city. I don’t care about political party anymore. As mayor, it does not matter. It only matters what you do. We need to find a way to disagree without being angry. Personally, I’m recommitting myself to doing a better job.”

The Elting Building, on Main Street, houses Brasserie 292, owned by Charles Fells, who’s frustrated by the way the narrative around COVID’s spread has focused so much on restaurants. “It seems like we’ve pigeonholed restaurants as the source of COVID, and that’s really sad,” says Fells.

Saving the Culture

Poughkeepsie’s civic identity and cultural vibrancy is bolstered by art venues and organizations that have been hit hard. The Art Effect is an organization that works with young people to express themselves, impact their community, and find tangible pathways to careers, through art. At the beginning of lockdown in March, that mission was initially hampered by not being able to meet in person, but they have persisted and found new pathways to success.

“We were, like so many, hit pretty hard because our programing primarily reaches youth through the schools,” says Art Effect Executive Director Nicole Fenichel-Hewitt. “I felt right away the lack of engagement opportunities for youth. We did a lot we haven’t done before. Every [artbased] business and agency has a different story. It’s heartbreaking to see institutions, like the Bardavon, shuttered for so long. There are fewer and much different opportunities for art right now, but the community in general has been so supportive.” Fenichel-Hewitt says public art like Madalengoitia’s nurse sculpture and street art created during the BLM demonstrations helped bring people together.

Art Effect emphasizes creating pathways to employment in the arts, and while the pandemic stifled many opportunities for program participants, the organization’s paid apprenticeship program with local video production house Forge Media presented an avenue for youth to work on media content for local businesses and organizations who needed content and virtual events as they themselves shifted online.

Before the pandemic, Art Effect had just opened their new Trolley Barn Gallery in the restored historic city building on Main Street. While COVID threw a spanner in the works, the Trolley Barn has proven an asset for instruction, as it was large enough for youth to spread out and have 12 young people working in their own art in socially distanced studio areas.

Youth have also been working with Mary-Kay Lombino, deputy director and curator at Vassar’s Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, to curate and run the Art Effect’s first international juried art show, which will include art from around the world selected by the kids, as well as some of their own powerful pieces. The show is titled “Homesick” and addresses the raw experience of the pandemic. Fenichel-Hewitt says the artists have created powerful works inspired by these unprecedented times. The exhibition will be on display from February 25 through April 1.

Perhaps the only thing that hasn’t changed during the pandemic is the natural beauty that surrounds the city. Scenic Hudson’s projects to protect, rehabilitate, and restore natural resources throughout the city, especially in disadvantaged neighborhoods, continued through 2020 and provided outdoor spaces for residents to safely escape lockdown.

“Scenic Hudson is committed to helping create healthy, livable, and sustainable communities that reflect the visions of people living in them,” says Zoraida Lopez-Diago, the director of Scenic Hudson’s River Cities Program. “This is so incredibly important on Poughkeepsie’s Northside, long plagued by racial, economic, and environmental inequality. Many Northside residents expressed the need to restore local Pershing Avenue and Malcolm X parks, making them safer and more inviting. At Pershing Avenue, construction is underway on a neighborhood farm that will increase access to fresh food—by providing plots for residents to grow produce and through an educational farm whose output will be shared with thousands of families via Dutchess Outreach.”

With so many people, businesses, and organizations working so hard to adapt to a COVID world, Poughkeepsie appears to be winning its war with the pandemic. It hasn’t been easy. There have been many losses—and there will still be more—but this is a city that’s use to fighting and accustomed to setbacks. While some of Poughkeepsie’s plans for the future have been delayed, it’s clear the community will not be denied.