Having a faith conversation with old and new friends is as easy as setting the table.

FAITH FEEDS GUIDE JESUS CHRIST

FAITH FEEDS GUIDE - JESUS | 2 BOSTON COLLEGE | THE CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY CENTER CONTENTS Introduction to FAITH FEEDS 3 Conversation Starters 6 • God Becomes Human by Johann Baptist Metz 7 Conversation Starters 9 • Embracing Lent by Patrick Nevins 10 Conversation Starters 12 • The Sacrament of Real Presence by Rev. Robert Imbelli 13 Conversation Starters 15 Gathering Prayer 16

The C21 Center Presents

The FAITH FEEDS program is designed for individuals who are hungry for opportunities to talk about their faith with others who share it. Participants gather over coffee or a potluck lunch or dinner, and a host facilitates conversation using resources from the C21 Center.

The FAITH FEEDS guide offers easy, step-by-step instructions for planning, as well as materials to guide the conversation. It’s as simple as deciding to host the gathering wherever your community is found and spreading the word.

All selected articles have been taken from material produced by the C21 Center.

FAITH FEEDS GUIDE - JESUS | 3 BOSTON COLLEGE | THE CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY CENTER

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

Who should host a FAITH FEEDS?

Anyone who has a heart for facilitating conversations about faith is perfect to host a FAITH FEEDS.

Where do I host a FAITH FEEDS?

You can host a FAITH FEEDS in-person or virtually through video conference software. FAITH FEEDS conversations are meant for small groups of 10–12 people.

What is the host’s commitment?

The host is responsible for coordinating meeting times, sending out materials and video conference links, and facilitating conversation during the FAITH FEEDS.

What is the guest’s commitment?

Guests are asked to read the articles that will be discussed and be open to faith-filled conversation.

Still have more questions?

No problem! Email church21@bc.edu and we’ll help you get set up.

FAITH FEEDS GUIDE - JESUS | 4 BOSTON COLLEGE | THE CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY CENTER

READY TO GET STARTED?

STEP ONE

Decide to host a FAITH FEEDS. Coordinate a date, time, location, and guest list. An hour is enough time to allocate for the virtual or in-person gathering.

STEP TWO

Interested participants are asked to RSVP directly to you, the host. Once you have your list of attendees, confirm with everyone via email. That would be the appropriate time to ask in-person guests to commit to bringing a potluck dish or drink to the gathering. For virtual FAITH FEEDS, send out your video conference link.

STEP THREE

Review the selected articles from your FAITH FEEDS guide and the questions that will serve as a starter for your FAITH FEEDS discussion. Hosts should send their guests a link to the guide, which can be found on bc.edu/FAITHFEEDS.

STEP FOUR

Send out a confirmation email a week before the FAITH FEEDS gathering. Hosts should arrive early for in-person or virtual set up. Begin with the Gathering Prayer found on the last page of this guide. Hosts can open the discussion by using the suggested questions. The conversation should grow organically from there. Enjoy this gathering of new friends, knowing the Lord is with YOU!

STEP FIVE

Make plans for another FAITH FEEDS. We would love to hear about your FAITH FEEDS experience. You can find contact information on the last page of this guide.

FAITH FEEDS GUIDE - JESUS | 5 BOSTON COLLEGE | THE CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY CENTER

CONVERSATION STARTERS

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. . . . To all who received him, who believed in his name, he gave power to become children of God.” — John 1:1, 12

Here are three articles to guide your FAITH FEEDS conversation. For each article you will find a relevant quotation, summary, and suggested questions for discussion. We offer these as tools for your use, but feel free to go where the Holy Spirit leads.

This guide’s theme is: Jesus Christ

FAITH FEEDS GUIDE - JESUS | 6 BOSTON COLLEGE | THE CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY CENTER

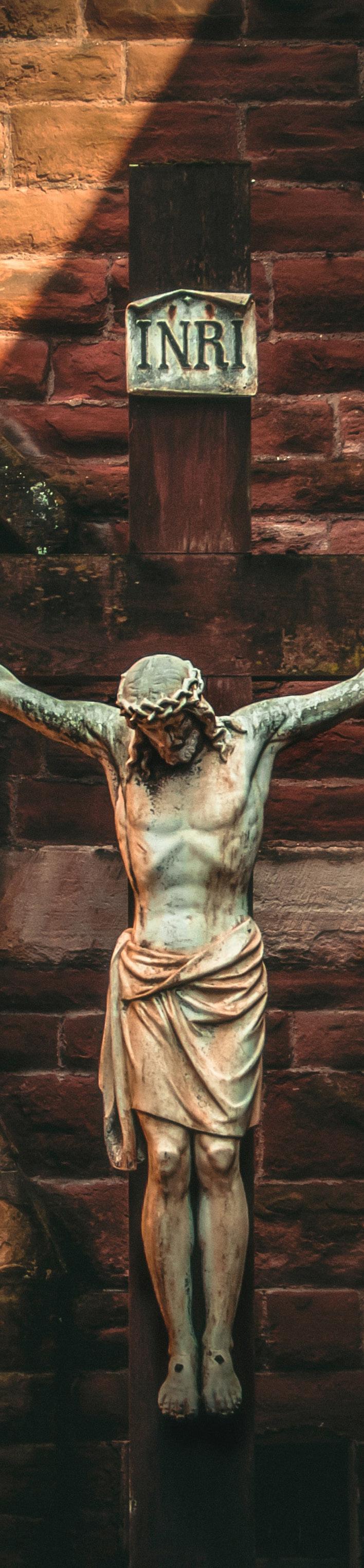

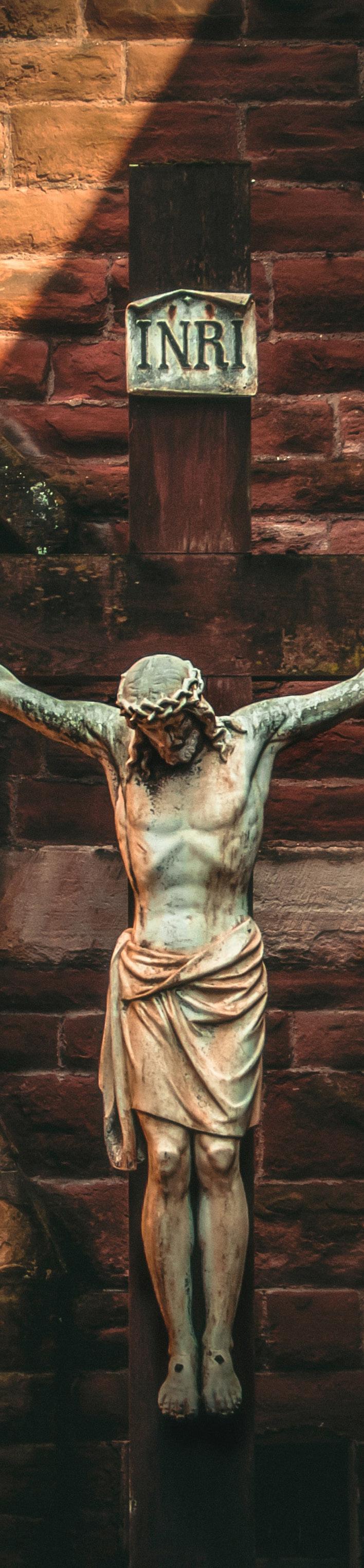

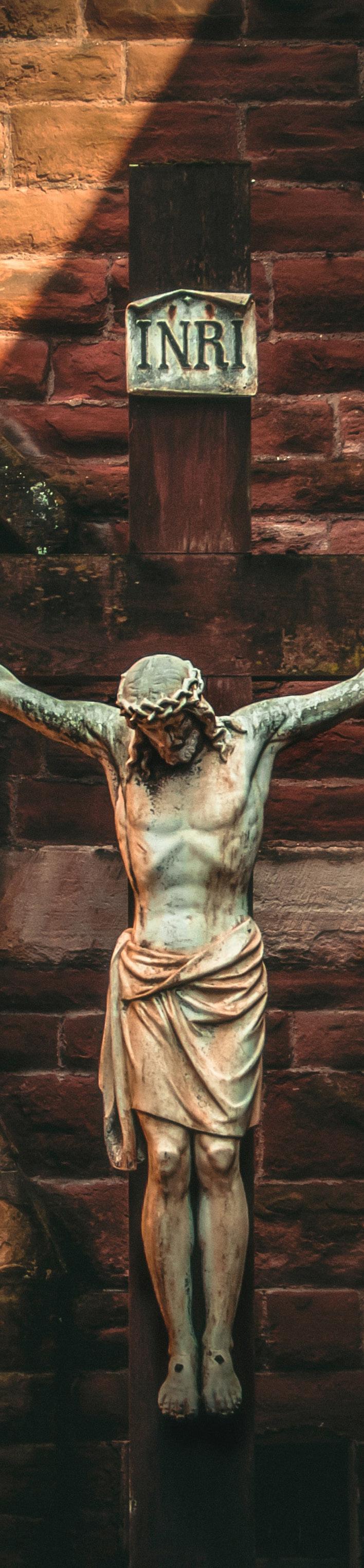

GOD BECOMES HUMAN

By Johann Baptist Metz

Then Jesus was led up by the Spirit into the wilderness to be tempted by the devil. And he fasted 40 days and 40 nights, and afterward he was hungry. And the tempter came and said to him, “If you are the Son of God, command these stones to become loaves of bread.” But he answered, “It is written, ‘Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceeds from the mouth of God’” (Deut. 8:3).

Let us overlook the external process involved in these temptations; let us try to focus on their underlying intention, on the basic strategy at work. We can then say that the three temptations represent three assaults on the “poverty” of Jesus, on the self-renunciation through which he chose to redeem us. They represent an assault on the radical and uncompromising step he has taken: to come down from God and become human.

To become human means to become “poor,” to have nothing that one might brag about before God... With the courageous acceptance of such poverty, the divine

epic of our salvation began. Jesus held back nothing; he clung to nothing, and nothing served as a shield for him. Even his true origin did not shield him: “He... did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself” (Phil. 2:6).

Satan, however, tries to obstruct this self-renunciation, this thoroughgoing poverty. He wants to make Jesus strong, for what he really fears is the powerlessness of God in the humanity he has assumed. He fears the trojan horse of an open human heart that will remain true to its native poverty, suffer the misery and abandonment that is ours, and thus save humankind. Satan’s temptation is an assault on God’s self-renunciation, an enticement to strength, security, and spiritual abundance; for these things will obstruct God’s saving approach to humanity... (As a matter of fact, Satan always tries to stress the spiritual strength of humanity and our divine character. He has done this from the beginning. “You will be like God”; that is Satan’s slogan. It is the temptation he has set before us in countless varia-

BOSTON COLLEGE | THE CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY CENTER ARTICLE 1

at Unsplash

Photo courtesy of Stephanie LeBlanc

FAITH FEEDS GUIDE - JESUS | 7

“Christ in the Wilderness” by Ivan Kramskoy (1872)

tions, urging us to reject the truth about the humanity we have been given.)

...Satan wants God to remain simply God. Satan wants the Incarnation to be an empty show, where God dresses up in human costume but doesn’t really commit the Divine Self to this role. Satan wants to make the Incarnation a piece of mythology, a divine puppet show. That is the strategy for making sure that the earth remains exclusively his, and humanity, too...

“You’re hungry,” he tells Jesus. “You need be hungry no longer. You can change all that with a miracle. You stand trembling on a pinnacle, overlooking a dark abyss. You need no longer put up with this frightening experience, this dangerous plight; you can command the angels to protect you from falling...” Satan’s temptation calls upon Jesus to remain strong like God, to stand within a protecting circle of angels, to hang on to his divinity (Phil. 2:6). He urges Jesus not to plunge into the loneliness and futility that is a real part of human existence...

Thus the temptation in the desert would have Jesus betray humanity in the name of God (or, diabolically, God in the name of humankind). Jesus’ “no” to Satan is his yes to our poverty. He did not cling to his divinity. He did not simply dip into our existence, wave the magic wand of divine life over us, and then hurriedly retreat to his eternal home. He did not leave us with a tattered dream, letting us brood over the mystery of our existence.

Instead, Jesus subjected himself to our plight. He immersed himself in our misery and followed humanity’s road to the end. He did not escape from the torment of our life, nobly repudiating humankind. With the full weight of his divinity he descended into the abyss of human existence, penetrating its darkest depths. He was not spared from the dark mystery of our poverty as human beings...

In the poverty of his passion, he had no consolation, no companion angels, no guiding star, no Father in heaven. All he had was his own lonely heart, bravely facing its ordeal even as far as the cross (Phil. 2:8). Have we really understood the impoverishment that Christ endured? Everything was taken from him during the passion, even the love that drove him to the cross.... His heart gave out and a feeling of utter helplessness came over him. Truly, he emptied himself (Phil. 2:7). God’s merciful hand no longer sustained him. His countenance was hidden during the passion, and Christ gaped into the darkness of nothingness and abandonment where God was no longer present...

In this total renunciation, however, Jesus perfected and proclaimed in action what took place in the depths of his being: he professed and accepted our humanity, he took on and endured our lot, he stepped down from his divinity. He came to us where we really are—with all our broken dreams and lost hopes, with the meaning of existence slipping through our fingers. He came and stood with us, struggling with his whole heart to have us say “yes” to our innate poverty.

God’s fidelity to humanity is what gives humans the courage to be true to themselves. And the legacy of his total commitment to humankind, the proof of his fidelity to our poverty, is the cross. The cross is the sacrament of poverty of spirit, the sacrament of authentic humanness in a sinful world. It is the sign that one person remained true to his humanity, that he accepted it in full obedience.

Hanging in utter weakness on the cross, Christ revealed the divine meaning of our Being. It said something for the Jews and pagans that they found the cross scandalous and foolish (1 Cor. 1:23). . . And what is it to us? Well, no one is exempted from the poverty of the cross; there is no guarantee against its intrusion....

Perhaps that is why Jesus related the parable of the wheat grain. Finding in it a lesson for himself, he passed it on to his Church, so that she might remember it down through the ages, especially when the poverty intrinsic to human existence became repugnant: “Unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it bears much fruit” (John 12:24).

Johannes Baptist Metz was Ordinary Professor of Fundamental Theology, Emeritus, at Westphalian Wilhelms University in Münster, Germany.

Published in C21 Resources, Fall 2014. Excerpt from Poverty of Spirit, © 1968, 1998 by The Missionary Society of St. Paul the Apostle in the State of New York. Paulist Press, Inc., New York/Mahwah, NJ. Reprinted by permission of Paulist Press, Inc. www.paulistpress.com

FAITH FEEDS GUIDE - JESUS | 8 BOSTON COLLEGE | THE CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY CENTER ARTICLE 1

GOD BECOMES HUMAN

“For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life. Indeed, God did not send the Son into the world to condemn the world, but in order that the world might be saved through him. Those who believe in him are not condemned; but those who do not believe are condemned already, because they have not believed in the name of the only Son of God.” — John 3:16-18

Summary

In this article, the famous theologian Johann Baptist Metz reflects upon the spiritual significance of Christ’s Incarnation, specifically His kenosis, which refers to His voluntary self-emptying. Philippians 2:68 describes Christ’s humble self-emptying: “[T]hough he was in the form of God, [Christ] did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form, he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death—even death on a cross.”

Questions for Conversation

1. How does Christ’s self-emptying inform the way we love and serve others?

2. Many perceive the Crucifix to be grim. How does Metz present Christ on the Cross as an icon of supernatural love?

FAITH FEEDS GUIDE - JESUS | 9 BOSTON COLLEGE | THE CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY CENTER

EMBRACING LENT

By Patrick Nevins

I was never really a big Lent guy. Advent was more my season. Who wouldn’t prefer a decorated Christmas tree to a stringy palm branch? Or who wouldn’t prefer singing “O Come, O Come Emmanuel” as the snow falls outside the church to singing “Dust and Ashes” on a cold and wet March Wednesday, or a crèche with angels, stars, and barnyard animals to the Stations of the Cross with Roman soldiers, thorny crowns, and lots of weeping people? Waiting for Santa Clause or waiting for a giant bunny? Yeah, Lent was just never appealing to me.

And then there was this whole giving up something. No chocolate. No TV. No beer! (I’m not sure what I was thinking that year). Meanwhile during Advent it’s all that and more—Christmas movies, Christmas cookies, and Christmas presents.

Who could possibly prefer Lent?

I do now. But it took the worst time of my life to get there.

On March 3, 2015, my alarm went off twenty minutes before it normally would. I poured a cup of tea, grabbed my Lent 2015 Prayer Book, and opened up to the daily readings. Lent was now in its second week and the rituals were in full swing. Twenty minutes of extra prayer in the morning, one or two daily masses during the week, and an extra stop at St. Anthony’s for confession. Of course, no pepperoni on my Friday night pizza and fasting when required. It was all set-up for me to get to Easter and look back and say, “Well another Lent in the books. I checked

all the boxes. Time to indulge in chocolate, TV, and beer.” But is that what Lent is all about: checking the boxes? Trying to live this pristine life of following all the rules for the sake of following all the rules?

That afternoon my dad called and told me it was best if I came home. My mom was in the emergency room. For the next three days I did not leave the hospital. What we thought was an innocent fainting was actually terminal brain cancer. Six months later my mom was gone.

The three days at the hospital all merged into one continuous, out-of-body experience. Like those dreams where you are half-aware that you are dreaming, except I couldn’t trick my brain to change the sequence of events. By day three I was exhausted and grabbed some shut eye on a bench in the ICU lobby. I was still wearing the same clothes I put on for work that morning when I opened the Lent 2015 Prayer Book. I hadn’t read it in three days, I hadn’t gone to Mass, and I had been eating the same assortment of pre-made deli meat sandwiches from the hospital cafeteria, even on Friday. I hadn’t even prayed. So much for Lent. All the boxes were left unchecked.

What came next was a feeling of utter desperation. Not only was it Lent, but my family was in crisis. Shouldn’t I be in prayer overload? I felt completely overwhelmed spiritually. I felt this need to go on a rosary binge to save my mom. Here she was facing death and it was up to me to pray seventy times, times seven. I kept replaying Matthew in my head, “Ask, and it will be given to you.” I was

FAITH FEEDS GUIDE - JESUS | 10

BOSTON COLLEGE | THE CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY CENTER

ARTICLE 2

Photo courtesy of Jacob Benzinger at Unsplash

faced with this monumental task—pray my mom back to health. How? Ten Our Fathers every hour? 100 Hail Mary’s a day? Shouldn’t I leave the hospital immediately and go sit in a church and light a million candles?

My thoughts were interrupted when my sister came out to the lobby. It was my turn to go sit with mom.

Fr. Michael Himes, a theology professor at Boston College, emphasizes the importance of remembering that we are made “like God,” but we are not God. It is not up to us to decide life and death. And that is not only okay, but dignified in God’s eyes. God so loved the idea of being human that God became one. In Himes’ opinion, there is no more radical ratification of the dignity of being human than the concept of the Incarnation. Himes calls our attention to the fact that “the Christian tradition does not say human beings are of such immense dignity that God really loves them. It does not say that human beings are of such dignity that God has a magnificent destiny in store for them . . . No the Christian tradition says something far more radical: human beings are of such dignity that God has chosen to be one.”

Himes encourages us to keep going. So what that God became human? What does that mean? It means that it is in the human life of Jesus, a human life marked by the pain and suffering of a crucifixion, where we learn who God really is. “The Christian tradition claims that absolute agape (which is the least wrong way to think about the Mystery that we name God) is fully, perfectly expressed in human terms in the life, death, and destiny of one particular person, Jesus of Nazareth.” Himes finishes the equation with this—if God is agape, and God became human in Jesus, then the life and death of Jesus teaches us who God is and how to experience God’s presence.

And that is what Lent is all about—experiencing God in newer and deeper ways than we have before. How do we do it? By being authentically human, even when that means confronting brokenness.

Fr. Greg Boyle, a Jesuit priest and founder of Homeboy Industries challenges us to re-envision how we encounter God. “We tend to think the sacred has to look a certain way . . . cathedral spires, incense, jewel-encrusted chalices, angelic choirs. When imagining the sacred, we think of church sanctuary rather than living room; chalice instead of cup; ordained male priest instead of, well, ourselves. But lo—which is to say, look—right before your eyes, the holy is happening. . .”

I slumped into the metal chair next to my mom’s hospital bed. She was fast asleep, recovering from brain surgery, with a dozen tubes and wires connected to machines. The room was peacefully quiet, filled only with the white noise of the ventilator humming in the background. She looked so frail.

There was only one thing to do—I gently placed my hand over hers and squeezed. It was that simple. God did not want me sitting vigil somewhere in a church, fasting from meat, with a sackcloth of ashes and incense. God wanted me here. Right in that hospital chair. Doing nothing more than holding my mother’s hand. Because lo—right before my eyes the holy was happening.

It was not up to me to save her. It was up to me to embrace her pain and suffering, embrace the limitations of humanness, and to say “I’m not here to cure, I’m here to hold it with you.” It is in these moments when we find God and encounter the holy. Because, as Boyle reminds us, “in Bethlehem, the words are printed in stone on the ground: ‘And the word became flesh . . . HERE.’”

In His final moments Jesus embraced not only His own pain, suffering, and limitations as a human, but embraced the pain and suffering of those around Him. In one of His final lessons, Jesus reminded His disciples—and us— what was most important: finding God on the margins of human limitation by feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, visiting the imprisoned, and accompanying the sick. Not only did Jesus preach it, but He lived it. During His final meal, amongst the chaos and uncertainty, He knelt before His disciples and washed their feet. The next day when, in the midst of His own suffering, He offered His comfort to the prisoner crucified next to Him.

...Let us remember that to understand who God is, to find God, to encounter the holy, is to follow the life and death of Jesus—who took on humanity. All of it. Even its pain and suffering. Let us focus on encountering God this Holy Week. How so? If I may suggest, get out of the church, don’t worry about your turkey sandwich you made for lunch on Friday, and hold the hand of someone who needs you. Maybe it’s taking a walk with your spouse after a tough day at work. Maybe it’s buying a coffee for the man who sits outside your office wrapped in a blanket. Maybe it’s stopping by your grandparents’ house just to say hi. Maybe it’s picking up the phone and calling that friend who really needs that phone call.

Lent is not about trying to be perfect. It’s not about checking the boxes. It’s about being authentically human. Don’t run away from the brokenness, the pain, and the imperfections, because in those moments we encounter God. As the women along the climb to Calvary learned, when we wipe the face of those in need, those suffering, those in pain, we see the face of God.

And that is why I love Lent. It’s the perfect time to be human…together.

Patrick Nevins, is the assistant director of grants and special projects in the Plymouth District Attorney’s Office. Originally in C21 Engage.

FAITH FEEDS GUIDE - JESUS | 11 BOSTON COLLEGE | THE CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY CENTER

ARTICLE 2

EMBRACING LENT

“Do you despise the riches of God’s kindness and forbearance and patience? Do you not realize that God’s kindness is meant to lead you to repentance? ...For he will repay according to each one’s deeds: to those who by patiently doing good seek for glory and honour and immortality, he will give eternal life; while for those who are selfseeking and who obey not the truth but wickedness, there will be wrath and fury.”

— Romans 2:4-8

Summary

Patrick Nevins recounts how his understanding of Lent was tranformed by his mother’s struggle with terminal cancer. As a young man, Patrick understood Lent to merely be self-denial for the sake of self-denial or obedience for the sake of obedience. Yet he discovers the truth of what Saint Paul teaches us: “For freedom Christ has set us free. . . . For in Christ Jesus neither circumcision nor uncircumcision counts for anything, but only faith working through love” (Gal 5:1-6). Lent is the Church’s invitation for us to “repent and believe in the Gospel”: God has overcome sin and death, so by abiding in Christ we can live freely by the law of love.

Questions for Conversation

1. Christ temporarily set aside His glory for the sake of saving us. He sacrificed a good for the sake of a more cherished good: you. How does Lent invite us to imitate Jesus?

2. We deny good desires for Lent in order to experience deeper freedom. For Patrick, this freedom looks like a simple walk with one’s spouse or buying coffee for a homeless person. What could this freedom look like for you?

FAITH FEEDS GUIDE - JESUS | 12 BOSTON COLLEGE | THE CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY CENTER

THE SACRAMENT OF REAL PRESENCE

By Fr. Robert Imbelli

William Butler Yeat’s “The Second Coming” contains what are, perhaps, the most-quoted lines of twentieth century poetry. “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world.” Written in 1920, the poem not only summed up the horror of the still young century, it seemed prescient of horrors yet to come.

Postmodernity may be, to some degree, a pretentious academic fad. But its soil is undoubtedly the collapse of an authoritative, life-giving center and the ensuing fragmentation experienced daily in culture, politics, and individual lives.

One result is the emergence of the “protean self,” imaginatively portrayed in Woody Allen’s film “Zelig.” Here is the self without a center, blending effortlessly into the most disparate situations and bound by no ultimate and lasting commitments — but also quite capable of murderous rage.

Brooding over the twenty-first century is no longer the specter of Marx, but that of Nietzsche. The “death of God” leads to an abyss of nothingness. While many strive to fill the emptiness with the ever-changing trinkets of consumerism or the endless titillations of the media, a few do so by indulging an unfettered will to power. And absence, not presence, seems to reign.

Faced with this cultural situation (one that Pope John Paul II called a “culture of death”), where is the Christian believer to find, in the words of another poet, T.S. Eliot, “the still point of the turning world”? Ultimately in the Eucharist, the flaming center of the world, the sacrament of real Presence.

At the central point of the celebration of the Eucharist, the priest announces to the congregation: “the mystery of faith.” And the congregation exclaims: “We proclaim your death, O Lord, and profess your Resurrection until you

come again.” In doing so we trace the temporal coordinates of the new world of faith.

“We proclaim your death.” The Eucharist celebrates, remembers, re-presents the once and for all sacrifice of Christ on Calvary. Christ descended into the abyss of death, the void of absence. He attained new and everlasting life not despite death, but by transforming death. Thus Christ’s followers are schooled, in the Eucharist, not to deny death in its many forms, such as disappointment, hardship, failure; but, in company with Christ, to transform the power of death.

For “we profess your Resurrection.” The Christ present in the Eucharist is the living Jesus and the disciples live through him and with him and in him. He is not a dim figure of the past to be studied at a distance, but the living one encountered in the today of faith. He declares: “I am the first and the last, the living One. I died, and behold I am alive for evermore,

FAITH FEEDS GUIDE - JESUS | 13

ARTICLE 3

BOSTON COLLEGE | THE CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY CENTER

and I hold the keys of death’s dominion” (Revelation 1:17-18). In the Eucharist we do not learn about Christ, but from him.

Still his presence remains hidden under sacramental signs. It is a real Presence that is not yet fully manifest. And so faith confesses: “Christ will come again” to sum up all things in himself, to “judge the living and the dead.” Only then will he complete the work of creation and redemption; and “God will be all in all” (1 Corinthians 15:28).

The Eucharist opens to faith a new world of persons in relation whose form and substance is the person of Jesus Christ. And it also calls forth the new personhood of the participants, their gradual transformation into living members of Christ’s body. “Here there cannot be Greek and Jew, circumcised and uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave, free, but Christ is all and in all” (Colossians 3:11).

The whole thrust of the Eucharist is to nurture a movement from fragmentation to integration: the broken bread becomes the salvific means for the gathering in of the many, the blood outpoured achieves the at-onement of the world. What is de-centered finds its center in Eucharist. Those who despair of meaning can find here God’s meaning and purpose.

The Eucharist, then, is pure gift, grace. God so loves the world that he gives his only Son. And the Son so loves us that he continues to give himself for the world’s salvation, nowhere more tangibly than in the Eucharist.

But the Eucharist is also imperative, task. It calls believers to allow the presence of Christ to transform both themselves and their world. In place of the protean, rootless self of postmodernity, the Eucharist fosters a centered self, free to give generously as he or she has so generously received.

What better name for this self emerging from the encounter with Christ in the Eucharist than a “eucharistic self,” one whose native language is thanksgiving? For as Paul writes to the Colossians: “whatever you do, in word or deed, do everything in the name of the Lord Jesus, giving thanks to God the Father through him” (3:17).

The deeds that flow from such a eucharistic self are deeds of service, in solidarity with the most needy members of Christ’s body. The participants in the Eucharist are sent forth to undertake works of justice and peace that help provide the human conditions for genuine thanksgiving. The eminently practical Epistle of James warns: “If a brother or sister is ill-clad and in lack of daily food, and one of you says to them, ‘Go in peace, be warmed and filled,’ without giving them the things needed for the body, what does it profit?” (2:15&16). The Eucharist both nourishes a eucharistic self and promotes a eucharistic ethic.

As is well known, the account of the Last Supper in the Gospel of John does not contain a narrative of the institution of the Eucharist, as the other gospels do. In its place we find, instead, Jesus washing the feet of his disciples and instructing them: “I have given you an example: as I have done to you, you also must do” (13:15). Therefore the injunction of Christ, “do this in memory of me,” repeated at every celebration of the Eucharist, embraces both the breaking of the bread and the ongoing service of others. Both these eucharistic actions are performed for the life of the world, for the fuller realization of Christ’s Presence in all.

Fr. Robert Imbelli, a priest of the Archdiocese of New York, is an associate professor of theology at Boston College. Originally published in C21 Resources, Fall 2011.

FAITH FEEDS GUIDE - JESUS | 14 BOSTON COLLEGE | THE CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY CENTER ARTICLE 3

FAITH FEEDS GUIDE - JESUS | 8

THE SACRAMENT OF REAL PRESENCE

“Very truly, I tell you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you. Those who eat my flesh and drink my blood have eternal life, and I will raise them up on the last day; for my flesh is true food and my blood is true drink. Those who eat my flesh and drink my blood abide in me, and I in them. . . . The one who eats this bread will live for ever.”

—John 6:53–58

Summary

Fr. Robert Imbelli reflects on the theological significance of the Eucharist, which the Church boldly describes as “the source and summit of the Christian life” (CCC 1324). The only way this statement could be true is if, in and through the Eucharist itself, God Himself is really, truly present. Remarkably, this is what Jesus and Saint Paul teach: that through communion, we continue abiding in Love Himself and His love becomes our life (John 6:53-58; 1 Cor 11:23-34). Yet because it is Jesus Christ in the Eucharist—Jesus, the gentle servant and companion of the poor—we are sent into the world to “announce the Gospel of the Lord” and “glorify the Lord by our lives.” Through communion, God invites us to rest in God’s love and to deepen the bonds of love with our Christian family. Then God sends us into mission to invite the whole of humanity into that same love.

Questions for Conversation

1. How does the Real Presence communicate God’s love?

2. John’s Gospel does not show Jesus breaking bread at the Last

FAITH FEEDS GUIDE - JESUS | 15 BOSTON COLLEGE | THE CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY CENTER

GATHERING PRAYER

Thomas á Kempis

In confidence of your goodness and great mercy, O Lord, I draw near to you, As a sick person to the healer, As one hungry and thirsty to the fountain of life, A creature to the creator, A desolate soul to my own tender comforter. Behold, in you is everything I can or should desire. You are my salvation and my redemption, My hope and my strength.

Bring joy, therefore, to the soul of your servant; For to you, O Lord, have I lifted my soul.

For more information about Faith Feeds, visit bc.edu/c21faithfeeds

This program is sponsored by Boston College’s Church in the 21st Century Center,

FAITH FEEDS GUIDE - JESUS | 16 BOSTON COLLEGE | THE CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY CENTER

/C21Center @C21Center church21@bc.edu (617) 552-0470 @C21Center bc.edu/C21

Photo by Toby Osborn on Unsplash