Ink

This year I am pleased to see two creative writing pieces in the magazine. There’s always a certain vulnerability when you put creative pieces in public, and I commend the courage of Julia and Jane in doing so. Two submissions, including Jane’s poem, are a response to the Auschwitz visit that took place early in the New Year, a trip that seems to have had a real impact on those who went.

There are also a number of articles that have been submitted successfully to essay competitions, such as the John Locke essay competition and the King’s College Entrepreneurship Lab essay competition.

The students certainly recognise the importance of going above and beyond the syllabus, and this magazine represents only a small proportion of a huge array of academic extension activities with which the students engage, and which enrich their subject knowledge. Thanks are due to my colleagues on the staff who encourage the students in their endeavours, and who always go the extra mile to help.

HumAnIty - A Study Of Ethical Issues Within Artificial Intelligence

6 Where Are The Limits Of Computability? An Arms Race Of Functions

If China Becomes The Leading Superpower, What Does That Mean For The People Who Live There, And What Does That Mean For Everyone Else?

Learning Wisdom From Failure

Was Personal Ambition More Important Than Revolutionary Principles In Napoleon’s Consolidation Of Power, During The Years 1799 To 1804?

A Trip To Auschwitz

All Doom And Gloom? A Reflection On The Wasteland By T.S. Eliot

Invisible Threads Between Cultures: Van Gogh And Japonisme

The Economics Of Healthcare Systems

Esther Greenwood: A First Glance Into Sylvia Plath’s Enigmatic Protagonist

Have Empires Throughout History Shaped The Societies We Live In Today?

Tackling The Gender Disparity In Football Officiating: A Call For Change

How Does Collaboration In Computer Science Support Social Impact And Innovation?

Amidst The Stars: The Discovery Of Exoplanets

Are Economically More Developed Countries Morally Justified In Interfering With The Development Of Economically Less Developed Countries On The Grounds Of Climate Change?

Why English Is So Weird: A Discussion Of The Phonological History Of English

Bowler

Medley

Platt

William Baker Head of Sixth Form

Cover painting by Ailith Howes: A Level 2023

Clemmie Dodson

HumAnIty - A Study Of Ethical Issues Within Artificial Intelligence

Caitlin Stevens

Upper Sixth

Over the last decade, engineers and computer programmers have made significant progress in creating what is known as, “machine learning algorithms”. These programs allow technological devices to adapt and grow from the situations they are placed in, enabling them to develop by themselves and decide the best choices to make in a particular scenario. This phenomenon has greatly expanded the abilities of machines to aid humans in dayto-day life. Mobile voice assistants, such as Siri or Alexa, make use of machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) development to become as responsive as possible to the user. You can ask them almost any question, and the immediate response will collate all the results received, either from an internet browser, or whichever service the user requires. Another common example of machine learning can be found in almost all social media services, where an algorithm takes into account which topics you engage with the most, and proceeds to display large

amounts of similar content as you continue to scroll. This is one of the many reasons why social media and “mindless scrolling” can be so addictive.

Despite the many helpful aspects of these “intelligent” machines, there are many ethical issues surrounding them, including those concerning privacy, autonomy, and morality. It is a commonly-known fact that a computer cannot think for itself; it simply follows the lines of code designed for it by a software engineer. As with many matters of ethics, AI ethics are constantly debated, and there can never be a unanimous decision as to what the best action is to take regarding these problems.

The first major issue with AI is that machine learning algorithms always have a chance of developing bias, including the type that is discriminatory against a particular minority of people or other subjects. One high-impact example of

this occurred within the Amazon hiring algorithm, when, due to machine learning, the algorithm began only to accept the applications of those who identified as male, due to the more frequent previous success of male applicants. This is perhaps due to the higher proportion of males in the industry than females at the time when Amazon used this algorithm. As of 2017 it is no longer used, mainly due to the bias that often occurred. The primary reason for AI bias is that it is not protected from human prejudice, and this was displayed in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the government made use of AI to help allocate predicted grades to students sitting exams. It led to students of ethnic minorities or a state-educated background being underpredicted as a result of the data the algorithm received, which drastically affected their chances of being accepted into university programs due to the dependence on predicted grades. Machine learning algorithms make use of data from

internet browsers and other platforms to form their “opinions” on certain subjects, as algorithms cannot think for themselves. As a result, moral issues such as racism and sexism are easily - and mostly unintentionally - adopted by programs. However, there are some instances where malicious bias skewing has occurred. One example of this was in 2016 when Microsoft released a Twitter chatbot named “Tay”. Less than a day after its release, the messages and tweets it received from users and internet trolls turned it from a useful service into a corrupted racist. Due to the onslaught of contradictory opinions Tay received, it began to spew out tweets that were not only filled with controversy, but also sometimes disagreed with each other entirely. A notable example is its description of feminism as both “a cult” and “great” almost within the same sentence. The bot adopted both the best and worst traits of humanity simultaneously, leading it to provide a very inconsistent service.

Another problem within these systems is often caused by the sheer complexity of their models. Machine learning algorithms are programmed in such a way that their adaptations become only possible for humans to understand if they possess extraordinary expertise within the field. There are some instances where the correlations made by algorithms have a direct effect on subjects, without any justifiable reason. One example of this is prevalent within the judicial setting. It has been proven that jurors are more likely to render a “negligence” verdict due to AI analysis of the court case than they would

be without the use of algorithms. The issue with this is that as AI algorithms become further developed, they may begin to have more dramatic effects on the outcomes of such critical functions as criminal trials, to the point where it may bring about an entirely wrong verdict, claiming the innocent to be guilty or vice versa. This could have a significant impact on societal safety, leaving some wanted criminals at large purely based on incorrect pattern recognition by an algorithm. Of course, programmers can minimise the window for error, but usually, this can only occur after an incident uncovers a weakness within the system. It is almost impossible to prevent every issue without knowing the scope of possibility.

The bot adopted both the best and worst traits of humanity simultaneously

impossible to place everyone under the hammer of consequence. At the same time, this accountability deficit leads to a more severe impact on the victims of incidents caused by AI, as until there is a determined perpetrator, sufficient compensation can never truly be reached. Denial of autonomy can be found in many different forms, such as direct interference, coercion, cognitive heteronomy, and misrecognition, and all of these can affect people’s lives in sometimes irreversible ways.

There have also been instances of machine learning algorithms affecting the autonomy of subjects. AI is commonly used to predict - and sometimes even determine - the outcome of situations and events, from gambling to highsecurity measures. The purpose of AI is to use automated procedures to mimic human cognitive functions, for them to execute actions only otherwise doable by trained and experienced specialists within a field. However, this makes it far more difficult to determine fault when a gross error occurs - who can be held responsible for the mistakes made by a computer program? The first assumption is to blame the programmer, but when it is often teams of tens or even hundreds of people creating these algorithms, it is

Despite the common use of AI to provide security to users and systems, one of the greatest issues produced by these algorithms is the invasion of privacy. There are so many different ways in which AI can damage the personal privacy of its subjects, whether inadvertently or not. Software that makes use of machine learning algorithms is not immune to the threats of cyber-attacks, and a data breach can be devastating to whoever is operating the algorithm, as it is likely that large amounts of confidential data are being stored within the many databases held by the program. Furthermore, the way AI functions, can sometimes lead to it gaining access to private details without a user’s consent, and algorithms can end up disobeying national and global data protection laws. Programmers and companies can find themselves in legal trouble due to the actions of AI, which are often out of their

The 2018 Data Protection Act helps to maintain the privacy of Internet users.

control. There is also the chance of AI being used in a more malicious sense to manipulate subjects and their data without their knowledge. This can lead to the targeting and profiling of certain “types” of users, and this can infringe upon the subjects’ abilities to lead their lives without influence from external sources. These sorts of problems are almost inevitable as long as AI systems are implemented, but programmers must take the necessary precautions to avoid the impact that these issues can have, no matter the scale.

I believe it is also wise to make a note of the psychological effects AI can have on humans. There are many types of AI used to simulate social interactions, appearing in the forms of interactive “chatting” games or toys and services, which can respond to any prompt from human speech. As these algorithms become more realistic and “life-like”, there is the possibility of degradation of a user’s social ability when it comes to communicating with other humans. This is because communicating with a machine can never be quite the same as talking to someone in a real-world setting, and although the line between the two is becoming increasingly blurred, there will always be subtle differences, which could bring about a greater social impact. Human emotional capabilities, such as empathy, trust, and true understanding are impossible to recreate using AI due to the simple truth that the computer cannot “feel” its own emotions. No program can replace real friends because you cannot form a relationship with something unless the emotions go both ways. Another way in which machine learning algorithms can affect social connection is through “hyper-personalisation”. AI is used to track everything you look at on social media, and it creates tailored advertisements to keep you interested. Social media becomes so addictive because of the large amounts of content which the algorithm confirms you are interested in through the way you

interact with the platform. The companies use these algorithms to give users a small rush of dopamine from being exposed to a lot of likeable posts, leading them to come back for more day after day. This certainly sounds exploitative, and although some platforms have means of attempting to

Jurors are more likely to render a “negligence” verdict due to AI analysis

reduce addictive tendencies, the companies make more money by having more uptime from users across the world, so it is unlikely that these algorithms will ever be significantly changed.

One other issue that seems less noticeable on the surface is that the outcomes produced by AI algorithms can be unreliable or simply dissatisfactory. This can be caused by the way the data is managed and produced, the design of

the algorithm, and the way the algorithm is used. If a program produces an unreliable or erroneous outcome that is then applied to other situations, there could be consequences affecting people on an individual or much larger scale. Negligence and cutting corners can cause many mistakes, ranging from personal misunderstanding to leaks of confidential government data and operations, which could lead to irreversible political tension in some extreme cases. Extra care must be taken by all programmers to maximise the reliability of these algorithms, even if that comes at a cost of its sophistication or complexity. Safety and quality should be the primary concerns of all those who endeavour to create AI, no matter its form and purpose. One current example of this is the new-found “genius” that is ChatGPT and its variants. Microsoft Bing’s implementation of this service has been discovered to “argue” with users over matters as small as the current date and time, with the AI being incorrect throughout the discussion.

In summary, there are many problems surrounding AI, and it is becoming increasingly difficult for programmers to evaluate and address all of these issues simultaneously. However, I do believe that part of the responsibility of a programmer is to ensure that the users of the algorithm are adequately protected and respected, and that they are made aware of the program’s purposes and how that could affect them. It is - most critically - necessary that programming teams create plans of action to deal with errors and mistakes if and when they do occur, and the awareness of these issues must be disclosed to customers all over the world.

Microsoft Bing's automated chat service argues with a user.

Voice-controlled assistants such as Siri can fulfil almost any request they receive.

Where Are The Limits Of Computability? An Arms

Race Of Functions

Alfie Greggs

Lower Sixth

For the past 81 years we have lived in a world containing electronic computation devices, and for roughly the last 40 we have lived in a world dominated by them. The development and progress of computing technology presents perhaps the fastest advancement of technology in all of human history. Throughout this period, the technology from five years in the past has often been considered primitive, and five years into the future – unthinkable. With this rapid development of technology now reaching unfathomably complex levels, clashing with the fundamental laws of the universe, and achieving seemingly impossible goals, the question remains: just where are the limits to the advancement of computation? Where is the boundary of what a computer can achieve? These are the underlying questions this article will answer.

The first step to answering this question is to clarify it: what is meant by “limits”, and what is meant by “computability”?

Computability is a problem that can be, “solved in principle by a computing device”.

The answers to these questions are not complicated ideas. When I refer to “limits”, I consider this to be the very physical limitations imposed on computation by the fundamental laws of reality; this is not the boundary of our current technology, but what – provided our species’ current understanding of the universe is somewhat accurate – is the line at which further advancement is intrinsically prohibited by nature. Whilst this is not a particularly exciting idea, it is necessary for scientific progress: it maps out what we are able to achieve, and what we need to work around. By “computability”, I will use the definition provided by the SEP (Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy), which states that computability is a problem that can be, “solved in principle by a computing device”. By “computing device”, I mean, “a functional unit that can perform substantial computations… without human

intervention”, as per the NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology). Finally, “computation” is the action of both mathematical and non-mathematical calculation.

Beyond these definitions, the more important question is: in what sense are we considering the limits of computation?

The first limitation this article addresses is a physical one, comprising the restrictions of classical, quantum, and relativistic mechanics on the size, speed, and efficiency of computing devices; this is where I will discuss the inevitable collapse of Moore’s Law in the coming years. The second limitation – the main focus of this article – is on the inability of any classical computer to solve certain problems in a reasonable amount of time, or at all. These problems stem from evermore complex and increasingly fast-growing mathematical systems - an arms race of functions against computation, in a sense.

It would be helpful to note here that this article will deal exclusively with classical computing. Although special variants – seen

in the quantum computing hype – have the same purpose, and much of the same core components (RAM, motherboard, secondary storage, etc), they function in entirely different ways. This leads to huge variations in where the limits of computability lie: some much sooner, some much further away.

The Atomic Limit

In 1965, businessman and engineer, Gordan Moore, made the astounding prediction that the number of individual components contained on a single computer chip would reach 65,000 by the year 1975. This equates to an increase by a factor of two, every two years. When this prediction became uncannily accurate during the mid-1970s, Moore refined his hypothesis into what is now known as Moore’s Law: the number of transistors in a single computer chip will roughly double every two years. Simultaneously, the cost and calculating time will be halved, and the processing power and data capacity will be doubled. This premise has led to decades of computational advancement in what can be thought of as a ‘golden age’ for computing, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy whereby the investment of time, money, and ingenuity to achieve a continuation of Moore’s Law, has paid off more than sufficiently through the progression of technology and the extension in capabilities.

However, as transistors are designed to be ever smaller (they are now composed of only a few hundred atoms each), the inherent size of atoms prevent the shrinking of transistors; it should be quite clear to see why a transistor requires a minimum number of atoms to exist. It is now quite possible to fit 2.6 trillion onto a single computer chip, and with this scale and density quantum mechanics causes further issues. Electrons running through the near-atom thick wires can jump to neighbouring wires through the process of quantum tunnelling, causing the whole system to break down as binary values lose the capability of being controlled. It is now widely accepted that Moore’s Law will terminate at some point during the 2020s. Incidentally, it is these same quantum mechanics that may provide a solution to this limitation.

The Function Limit

What I consider to be the primary limit to computability – and indeed so too by the entire branch of philosophical mathsorientated computer science, referred to as computability theory – is the unfathomably

fast-growing functions conceived as a direct challenge to our understanding of what is computable. In fact, even since before the first functioning computer was assembled, this field has been dedicated to defining, and challenging, what is computable. Using an arsenal of obscure mathematical operations, complex logical programming, and philosophical parameters, computer scientists, mathematicians, and philosophers have worked tirelessly to outwit technology. In 1936, these scientists claimed their first victory over computability. To this day, it is by far the most famous example of a problem impossible for a standard computer to solve, and its creator - the most famous computer scientist to have lived.

code. Now it needs to be stated that any computation or algorithm is equivalent to the operations of some Turing machine, as per the Church-Turing Thesis. A Turing machine is an abstract mathematical concept of a computer precursor that manipulates a tape of binary values, according to a table of instructions. This allows for simplification and generalisation of computers. Turing proved this by imagining the following scenario: let H be a program that will always state whether a program will halt, and let O contain H and perform the opposite of H’s output. If a halting program is inputted into O, then O will continue running forever; likewise, if a non-halting program is inputted, then O

This predicament is called the “halting problem”. What makes the halting problem so special is the fundamental impossibility this scenario preposes. Even an infinitely powerful computer would offer no gain to finding a solution. Other functions produce numbers so vast, that supercomputers the size of planets would be unable to accurately calculate them before the heat death of the universe. These boundaries are more than mere physical limitations provided by the size of atoms in our universe, but inherent properties of existence and reality.

The argument that the halting problem poses is that it is impossible for a Turing machine to always decide accurately whether a program will terminate, purely based off the input parameters and arbitrary

will halt immediately. Should the program of O be inputted into itself, then for whatever H outputs, O will perform the opposite, thus contradicting the decision made by H. The result is that either H provides an incorrect answer (therefore proving it to be inaccurate), or continues to run indefinitely itself. This paradox thus disproves the existence of a true H through contradiction. In a somewhat refreshing way, the halting problem proves there is more to thought than mere computation and therefore gives hope that computers can never truly replace humans.

Through a more general lens, abstract logic computability theory has explored the boundaries of computation and formulated precise mathematical understanding

Figure 1, the set notation for Rayo's Number

Figure 2, as all branches of the first tree are contained within the third, the forest dies

of proof and solvability, consequently directing further mathematical study and technological advancement. Beyond the first example of the halting problem, research in this field has been largely through complex mathematical and logical systems of calculations, mathematical paradoxes, axioms, and the scale of integers. This article will discuss four such calculations, these being Rayo’s Number, Graham’s Number, the TREE function, and the Busy Beaver function. They are all defined through complex and somewhat philosophical quasimathematical expressions.

Rayo’s Number: Agustin Rayo defined this value in 2010 using second order set theory, and as such, poses a challenge to understand. However, in semantic form it is the smallest number bigger than every finite number that can be formed using first order set theory with 10100 symbols or less, where first order set theory is the collection of standard mathematical symbols.

Graham’s Number: Whilst in itself an integer value, it is actually a specific output of Graham’s function. To explain this function, we must first consider the order of operations. The most basic is succession, order 0: where f(n) = n + 1. The next three are addition [f(n) = n + a], multiplication [f(n) = n x a], and exponentiation [f(n) = na]. These three operations, orders 1, 2, and 3, comprise the entirety of standard calculations in all of maths, where each order is formed from the previous order when a = n.

However, this is not the limit of operation orders – the next is tetration, (order 4) [f(n) = an], and then pentation, (order 5) [f(n) = ¬an]. At this point, it is worth introducing what is known as arrow notation: starting from exponentiation n↑a, each further arrow represents a further order of operation. Graham’s function starts with the value g1, defined as 3↑↑↑↑3, and proceeds to g2, defined as 3↑↑↑↑↑…3 with g1 arrows between the two threes. In general, gn = 3↑↑↑↑↑…3 where the number of arrows equals the value of gn1. From this, Graham’s Number is defined as the value of g64.

The limitation originates from the inability for all computational problems to be solved algorithmically

TREE function: Again, I will describe the TREE function semantically, although as before it can be defined through set theory. It is more complex to understand than the previous two numbers but as a basis TREE(n) can be thought of as the number of unique ‘trees’ that can be formed from n types of node. In more detail, a tree is a collection of connected nodes, which may branch off any number of times, but may never form a loop. A forest is the series of trees formed and the value returned is the maximum size of the forest, depending on the input. The first tree in the forest

is composed of up to 1 node, the second up to 2 nodes, the third, 3 nodes, and so on. However, the entire forest dies if any previous tree is contained within another tree, specified as when all the nodes of said previous tree can be found within the later tree sharing the same nearest ancestor. See Figure 2 to better understand this. For example, TREE(1) starts off with a single type 1 node, but so must tree 2. Therefore, the largest living forest size is 1 tree: TREE(1) = 1. TREE(2) starts off in the same way, but with the extra type of node, tree 2 can now be two type 2 nodes connected, leaving tree 3 as one type 2 node. As a smaller tree cannot contain a larger one within itself, this is still allowed. This gives a forest size of 3. Beyond TREE(2), the TREE numbers break free of the early restrictions and can soon contain huge numbers of nodes, and as such their magnitudes can no longer be comprehended, yet remain finite in value.

Busy Beaver function: The final function I wish to discuss is the Busy beaver function [BB(n)]. To describe this function, imagine an infinite binary string of 0s with a single Turing machine acting on it. The Turing machine is in a specific state, containing six pieces of information: whether to flip the bit, which direction to shift along the binary string, and which state to transform into –these values exist separately for whether the bit read is 1 or 0. The number of states is n, and the value returned is the largest finite number of 1s produced when the process terminates, where halting is a separate possible state. What makes this function particularly notable, is the clear link to the halting problem, demonstrating that it is fundamentally impossible for a normal computer to compute values for the function beyond a certain point, never knowing whether the current set of states returns a finite value or will just keep cycling for all eternity. Furthermore, to prove if a specific n-state machine halts would involve disproving cornerstone mathematical theorems, such as Goldbach’s Conjecture or the Riemann Hypothesis. The Busy Beaver function is not computable, as it cannot be defined as a finite series of operations, and the removal of this restriction is what makes it the fastest growing fully defined function in existence.

For reference to the size of these numbers, even if the symbols of Rayo’s Number were

Agustin Rayo

to be written down at a rate of one symbol per Planck time, the smallest possible division of time, the universe is not likely to last long enough for the writer to finish – and that does not even begin to make a dent on writing out the number. And, if a person was to imagine Graham’s Number, the energy required to store every digit in the human brain would be greater than the energy density needed to cause space-time to collapse into a black hole. Even the proofs that these numbers are finite or too long, can’t be explained; instead, this branch of mathematics relies upon proofs of proofs for theorems. In fact, there is a point at which, certain theorems lose their ability to even be proved, preventing definite solutions ever being found to certain conjectures.

Now consider all these as functions ([Graham(n) = gn], Rayo(n) = largest number using n symbols). None of these numbers are computable beyond a very low boundary, whether this is because they are impossibly large, undefinable, clash with other theorems, or are simply paradoxical in nature. Yet if you were to order them in rate of growth, using abstract logic it can be seen that TREE(n) overtakes Graham(n) when n = 3; BB(n) overtakes TREE(n) when n = 748; and Rayo(n) overtakes BB(n) when n = 7339. In a facetious way, the Busy Beaver chops down the TREE. They form a brief insight into the boundaries of computability and pose the question: what is the purpose of computability theory? For all intents and purposes these numbers can only be operated on using abstract non-finite

mathematics, such as ordinals. What they exhibit is a challenge to the very nature of computation, encouraging new ways of thinking. They bring about awareness of obstacles facing the advancement of technology and mathematics, allowing research to begin into innovative methods to bypass these restrictions. They confront our perceived limitations of computer science and describe limitations on technology, such as artificial intelligence, by allowing types of problem to be identified and characterised on solvability.

Artificial Intelligence Complication

For a slightly more applied example, I will discuss how the limits of computability affect the potential of AI technology. Artificial intelligence can be broken down into two main subsets: deep learning and neural networks, with neural networks themselves forming a subset of deep learning. Neural networks mimic the structure and function of the human brain, hence the name, and are by far the most advanced form of AI at the time of writing. As AI gradually infiltrates all areas of our daily lives, it inevitably finds itself in highrisk situations, where trust in the neural network needs to be absolute. In order for the AI to be considered trustworthy, it must demonstrate that it will reliably return an accurate decision, regardless of the input data. To explain this, I will introduce the concept of stability. Stability can be thought of as the degree to which the neural network alters from a slight modification to its input

data. The network is reliable if it is stable, and stable when consistent despite small changes.

The limitation originates from the inability for all computational problems to be solved algorithmically, a paradox discovered by Turing and Gödel. Fundamentally, there are a multitude of stable neural networks that can produce accurate outputs to corresponding problems, but there exists no such algorithm or mathematical method to formulate these networks. What is produced instead are periodically accurate, yet unstable, networks. In the same way as before, no matter the quality or quantity of the training data, the time or processing power allowed for computation, the task remains insolvable. Furthermore, for similar reasons, neural networks cannot yet describe their confidence in a decision and it is extremely difficult to convince one that it has generated an error. This all leads to limitations regarding the ability of the AI, and as a result, whilst effective networks can be produced with relative ease, they cannot be trusted as to always give reliable outputs. From this, future decisions need to account for the potential lack of stability when installing AI into high-risk roles, and research can be focused on better understanding artificial intelligence including finding new non/ quasi-mathematical ways to formulate suitable neural networks. And all this can be achieved in part through computability theory.

If China Becomes The Leading

Superpower,

What

Does That Mean For The People Who Live There, And What Does That Mean For Everyone Else?

This essay achieved a commendation in the John Locke Institute 2023 Global Essay Prize

Max Bowler

Upper Sixth

“I fear that Americans are not psychologically prepared for the day when America will become number two ” (Kishore Mahbubani, “When China Becomes Number One”).

The idea of a superpower other than the US is a concept very much ‘foreign’ to Westerners. For 30 years, America has not needed to defend its position as top of the food chain. American hegemony is the academic consensus, best outlined by John McCormick in his 2007 work, European Superpower; “It seems that no mention of the US as a super-power is any longer complete without the adjectives ‘sole’, ‘only’ or ‘lone’” .

The world's leading superpower will always be the state with the ability to project the most strength and influence globally. Today, the rise of China is watched eagerly by governments and academics, with its explosive economic growth turning the former communist state into the world's second-largest economy .

These economic growth rates and the rapid increase in the standard of living in China makes it an emerging power with much potential. In this essay, I will evaluate both the domestic and international impacts of China becoming the world leading superpower. I will focus on how China’s economic plan will raise the living

standards of the Chinese, as has already been happening for the last thirty years. In addition, I will examine whether the authoritarian approach of the Communist Party of China (CCP) will persist once China claims the top spot, or whether democracy will be phased in.

From my (a western) perspective, China’s rise disrupts the status quo of the previously uncontested US-EU dominance. The state of foreign relations and affairs will surely change, as history proves each time a nation rises to the top. I will examine China’s foreign policy, and how that will impact international relations in the future. China has become the engine for the modern Western economy, with its near monopoly on manufacturing, the essay will explore how China becoming the leading superpower will affect the global economy.

Domestic impacts of China as the world superpower Economic

The way in which China becomes the leading power will determine the impact it has on both its population and internal affairs.

China’s economic growth is the heart of the country’s emergence as a global power

and is the most obvious route for China to become the world leader.

The speed of the Chinese economy's post-communist transformation is remarkable. Since 2000, its GDP has sustained an average growth rate above 9% . Comparatively, the US has sustained meagre growth of 2.13% . This prolonged period of sustained growth has filtered through to the Chinese consumer. Crucially, the average Chinese worker has enjoyed a greater growth in GDP per capita, measured in Purchasing Power Parity - PPP). Since 2000, the US GDP per capita PPP has risen just 26.9%, while the Chinese have seen theirs increase by 510% .

This increase in China’s consumer income is equal to the increase in China’s total GDP, indicating that Chinese households are fully reaping the rewards of their surging economy, rather than large corporations being the main recipient.

Simultaneously, poverty is being eradicated at the same rate as China’s growth. The World Bank measures poverty in gross terms; it was less than US$2.15 a day in 2017 (PPP). According to their data, the Chinese poverty rate has shrunk from an overwhelming majority of 72% in 1990, to 0.1% in 2019. This has led to China being propelled from a Human Development Index score of 0.484 in 1990, to 0.768 today.

Like so many other metrics, this growth outperforms the current world superpower, the United States.

These are just a handful of the countless statistics that suggest the Chinese economy is en route to overtake America’s, and that this economic growth does have a profound impact on China’s population. This is the academic consensus; China will, in the 21st century, become the leading economy. This is the first step to becoming the leading superpower.

The evidence suggests the Chinese individual is in a better position to reap the rewards of China’s economic growth than Americans were at the start of the USA’s rise in the early 1920’s. This should eventually lead them towards a level of prosperity not seen even in 20th century America.

The position of the Chinese is the result of:

a) Their income growing much faster

b) This income is being distributed fairly amongst the entire Chinese society. Largely because wealth inequality is lower in China than America. (Which is unsurprising for a formerly communist state).

Most importantly, the standard of living is improving at the same rate as the

economy. For the Chinese population, their nation’s route to becoming a superpower is primarily economic. If China continues this economic path to become world superpower, then the standard of living for the Chinese population should become worldleading as well.

Political

China must utilise their strengths to exert their influence

The Chinese state is widely considered to be one that wields immense power and control, at least compared to Western domestic governance. On the democracy index by the Economist, China ranks 156th in the world1, putting it lower than Yemen, a failed state, engulfed by civil war, with no government control over most of the country.

The trend between democracy and economic prosperity is clear; democracies are wealthier (they have a higher GDP per capita) than autocracies or failed states.2 China goes against this trend, with a 156 democratic ranking despite a GDP per capita ranking of 71: a substantial difference.

The Chinese state clearly believes economic growth and building wealth is a priority over democratic rule. Scholar, Yongnian Zheng, outlines the Chinese

point of view in his work, ‘Development and Democracy: Are They Compatible in China’ . He concluded that, “While the state legitimizes the ‘fifth modernisation’ [democratisation], economic growth is doubtless the state’s most important goal.” Zheng does not believe that the Chinese Communist Party rejects democratic rule ideologically, but sees the prosperity of the people as the priority over the rule of the people.

For the Chinese population, we can expect greater income and wealth growth before democratic rights are granted. From the perspective of the Chinese individual, the continuation of political authoritarianism is a matter of personal opinion. While some would forgo some economic growth in return for a more democratic society, an equal number would prefer to see their income take priority. The CCP seems to fall on this side of the fence.

What is clear is either Chinese democracy will begin, or the economy will continue to flourish.

Global impacts of China as world superpower

How influential will China be?

Alongside the internal and economic changes within China, which determine the extent of its hard power, Beijing can put these economic capabilities to diplomatic use. Joseph Nye originally used the term ‘soft power’ to describe the influence a state can exert, without coercion or force (‘hard power’). Rather than pressure their allies, soft power is the ability to persuade allies through attraction.

However, Nye argues throughout his work, ‘Soft Power’ , that the attraction and diplomatic power can only be influential if the state has enough hard power (considerable economic, military, and institutional reputation, all of which could be used to coerce others). In the case of China, the use of subtler economic power to attract allies through investment is preferred over threats. Like Nye’s argument, China must utilise their strengths to exert their influence. As the economic powerhouse they now are, their economy is the primary tool for building alliances.

Nowhere is this clearer than through China’s ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI). This is an investment program that

supplies developing countries with infrastructure financing. An article in the ‘Indian Journal of Asian Affairs’, by Nguyen Thi Thuy Hang, outlines the influence this program has; “The One Belt and Road Initiative can help expand China’s economic connections and foster China’s economic influence”.

From a Western perspective, the influence China is gaining through this initiative threatens the status quo. This program of an emerging economy financing other emerging economies to help them develop is a very forward-looking approach. We may not see the impact of this for some time. There is academic speculation on both sides of the argument; some see it as a significant soft power asset, whereas others deem it poor value for money. Jan Voon and Xingpeng Xu, in the ‘Asia-Pacific Journal of Economics’6, argue that states receiving BRI financing will have a deeper economic relationship with China, but Chinese influence will be limited if Chinese manufacturing and a Chinese workforce are substituting the economy that is trying to grow. I doubt this, as the new infrastructure will be a method of gaining popularity for the (mostly) dictatorial governments that are targeted under the BRI.

China’s influence will grow regardless of the BRI. Every emerging power seeks to assert influence as far as possible, just like every other nation when rising to the top: Britain, the United States, and now China. The BRI is unique in that

it deliberately targets the undeveloped nations for political influence, rather than looking to exploit economic resources (like the previous superpowers did). China could prove to be very popular in emerging economies around the world. This soft power is a long-term investment in influence, rather than a method of neoimperialism.

Economic Interdependence

Being the second largest economy, China is a focal point for much of global trade. Much of this is an interaction between China and the developed world. Goods for western, high-consumption lifestyles must be sourced, and this is the market China has targeted. Manufacturing is the heart of the Chinese economy. China has a huge trading deficit with the United States, with the US exporting $124bn of products to China but importing a further $437bn of Chinese products . This makes China the United States’ biggest goods single trading partner, with trade amounting to $559bn in 2020.

This is a similar story for the EU, with China as the main supplier for European products. Currently, there is a $385bn import of Chinese products, with that growing to over $600bn post-pandemic .

Neither faction finds this ideal; the US finds itself to be the biggest contributor to its greatest economic competitor, while China has found its growth dependent on

US-EU trade, with over 35% of its exports going to the West.

This may seem like a mutually beneficial relationship, but with the emergence of non-Western economies (such as the BRIC or MINT nations) expected in the future, China will be able to reduce its dependence on the West more than the West can reduce its dependence on China. This could become a bargaining chip for China in the future, and in turn could have a significant impact on negotiations over contentious disputes, such as the sovereignty Hong Kong or Taiwan, where Western political protection exists. The West cannot find itself at severe disagreements with China, for fear of losing the trade upon which its economy is dependent.

Conclusion

Chinese optimism looking forward is very much justifiable. Living conditions will continue to rise, potentially alongside democratic rights. The Chinese economy should propel China into the ranks of the most developed nations. For the rest of the world, it depends with which side they are affiliated, as the West’s power will be slowly eroded by China on the global political and economic stage. States may seek to align themselves with China, further weakening the West. Both the academic consensus and the data suggest the mid 21st century as being the beginning of the Chinese era.

Learning Wisdom From Failure

Submitted

to the King's College Entrepreneurship Lab Essay Competition

Jago Howes

Upper Sixth

Samuel Smiles – “We learn wisdom from failure much more than from success. We often discover what will do, by finding out what will not do; and probably he who never made a mistake never made a discovery.”

Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk - these are just a few names of worldrenowned entrepreneurs that have each attained their individual successes. With a combined net worth of $617.7 Billion, it is hard to believe that they have encountered much failure. However, it is failure that they are indebted to for their riches, as, without it, they would likely not have equivalent wealth of an entire country’s GDP. As people, they all celebrate extreme differences in not only themselves, but also their companies - in fact, it’s hard to find any aspects of similarity between any of them (perhaps aside from lavish mansions and grandiose private jets). And yet, they all share one thing in common… you guessed it – failure.

It is no coincidence that prominent entrepreneurs have countless quotes on their successes and failures; they have all learnt the invaluable lesson – failure teaches us far more than success – a concept that is reinforced by none other than Bill Gates:

“It’s fine to celebrate success but it is more important to heed the lessons of failure”

“It’s fine to celebrate success but it is more important to heed the lessons of failure”. More often than not, entrepreneurs experience numerous failed ventures before

creating a successful business model. As a concept, I believe that failure is one of the most valuable tools to an entrepreneur, as it highlights what went wrong, whilst simultaneously encouraging thought on how to get it right next time. It also plays a part in making us more resilient, something that is ultimately crucial to long-term success. Failure only allows the experience of success to come to those who are unwilling to admit defeat in the

face of disaster. This is why you rarely encounter a successful entrepreneur who is not passionate about what they do, or sees entrepreneurship as a ‘hobby’. If you were to research conventional characteristics of entrepreneurs, the sort of skills that commonly appear are determination, tenacity, discipline, resilience, adaptability, and empathy. All of these characteristics are taught, not by a teacher at school, not by your boss, but by experience; in particular, the experience of failure. Natalie Ellis, CEO of BossBabe (a firm that has successfully supported over 100,000 ambitious women within the business sector), demonstrates this perfectly as, “one of [her] first ever business partnerships broke down so badly that [she] had to bring in lawyers to help decide who would keep the business and who would be bought out”. However, she went on to admit that the process had made her even “stronger” as a businesswoman, and that it has allowed her to realise that, “actually, I am enough.”

Many hold the common misconception that entrepreneurs, such as Bill Gates, started Microsoft as their first and only venture.

However, they could not be more wrong. In reality, Microsoft was the birthchild of the lessons Gates learnt from the failure of his original company – Traf-O-Data6. This revolved around a technological system that fed traffic information back to people for whom it had value, such as government authorities or engineers. Great idea, right? Wrong. The concept ultimately failed, forcing the business into liquidation. Yet, unlike the majority who may lose motivation in the face of disappointment, Gates saw the experience, skills, and mindset that he had gained from Traf-OData’s failure as an opportunity to set up Microsoft, the company that he is now most renowned for, with Paul Allen merely a few years after Traf-o-data’s downfall. Gates’ story is similar to countless other successful entrepreneurs. He accepted failure, understood what he did wrong, and started again. Failure was the key he needed to unlock his multi-billion-dollar empire.

Another example emanates from Amazon founder, Jeff Bezos, who, when constructing Amazon’s business model, made some crucial and seemingly obviously problematic mistakes. Firstly, Bezos had a keen vision to store toys in factories in preparation for the Christmas season. Therefore, he permitted the purchase of over 100 million toys, which were to be stored in Amazon warehouses. However, by the new year, half of those toys remained unsold, forcing Amazon to give the majority away due to a lack of storage space. This extreme miscalculation of demand from Bezos led to a substantial setback in not only his company’s success, but also his morale. In addition, when Amazon first launched, consumers exploited a software glitch, allowing

them to buy a negative number of books, meaning the company supplied these consumers with free credit. Whilst it may be challenging to believe that a business that literally handed money out may ever be successful, Amazon is now the premier platform for online shopping, dominating US e-commerce sales with nearly 50% market share, worth a revenue of $514 billion in 2022. So, how does a company go from losing money, to earning $4,722 every second? It’s simple really – Bezos learned from his initial mistakes and committed to a policy of continuous improvement, constantly learning from errors and adapting as a result.

Whilst it is possible that learning from success can be beneficial, the fundamental issue is that when we succeed, we don’t

tend to take time to consider what went right and more importantly, wrong. The undeniable fact is that the most valuable asset that all these entrepreneurs have obtained is their ability to accept failure and understand how they can change in order to benefit from future success. As people, we must eliminate the shame entailed with experiencing failure. We see the concept of failing as something to be embarrassed about and forgotten, whereas, when embraced and harnessed, it becomes apparent that failure is undeniably fundamental to triumph. My final thought is this - as a society, we must understand that, “failure is success in progress” (Albert Einstein), and that failure is not the end of the road, but merely the beginning of a successful journey.

Natalie Ellis, CEO of BossBabe

Was Personal Ambition More Important Than Revolutionary Principles In Napoleon’s

Consolidation Of Power, During The Years 1799 To 1804?

Napoleon consolidated his power fundamentally through his own personal ambition, which is reflected in the various authoritarian changes that he made to government. The extent of these authoritarian changes can be carried through to the somewhat enlightened religious and educational reforms. Though these reforms played a significant role in granting Napoleon more support, they appeared to benefit the people and provided a restoration of the revolutionary principles, thus undermining the impact that personal ambition had on consolidating Napoleon’s power. In summary, personal ambition was more important than revolutionary principles in Napoleon’s consolidation of power, as it meant that he could dominate the apex of power and seize total control over France.

Primarily, Napoleon immensely consolidated his power through the authoritarian changes that he made to the government. The establishment of a sham democracy meant that the power of the elites became completely emasculated, as Napoleon immensely reduced their influence within the constitution by creating the Senate and Council of State, and replacing the Council of Ancients and the Council of 500 with the Legislature and Tribunate. This display of personal ambition consolidated Napoleon’s power, as he could create the illusion that there was an elaborate constitution, which in reality was only pretending to be democratic. Additionally, to gain further control over the government, Napoleon carried out plebiscites in 1800, 1802, and 1804 to appear to be providing an enlightened democratic society for the people, although this façade was undermined by the underlying autocratic features that granted Napoleon the power of Senatus Consultum. This meant that he could override anyone and appoint the members of the Senate and Council of State, which ultimately fed into his aim to possess total control over France. Furthermore, Napoleon’s personal aim of creating an indirect democracy that he could dominate, was carried out by the further changes

Clementine Dodson

Lower Sixth

made to the constitution, which resulted in Napoleon being declared Consul for 10 years in 1800, Consul for Life in 1802, and Emperor in 1804. These reforms had a monumental impact on the political system, as they diluted the strength of the nobility and ultimately cemented Napoleon’s power even further. This led to the creation of an autocracy that significantly consolidated Napoleon’s power, as he could appear to be restoring stability to France. In spite of this, Napoleon was a liberal authoritarian, who harnessed the loyalty of the people through his policies of amalgame and ralliement.

These reforms diluted the strength of the nobility and ultimately cemented Napoleon’s power

Personal ambition proved to be more important than revolutionary principles in Napoleon’s consolidation of power in the area of religious reforms, which proved to enhance his support and elevate his authority over the Catholic Church. The

1802 Concordat enabled Napoleon to bring about a united France by ending the religious schism, leading to a further boost of his power. The concordat also granted Napoleon vast amounts of authority as it meant that the Pope was forced to recognise the new regime, church lands were not handed back, and the clergy were appointed and paid by Napoleon himself. This meant that the influence that the Pope had over the Catholic Church became completely emasculated, as Napoleon was able to successfully exploit Catholicism for his own personal gain. Furthermore, the creation of the Organic Articles in 1802, established religious toleration of Jews and Protestants, which, once again, helped to consolidate Napoleon’s power as it led to an increase in support and widespread devotion towards him. However, elements of the religious reforms did serve to uphold revolutionary principles and contributed to Napoleon’s consolidation of power. The reforms largely benefitted the people; in 1799 Churches were declared open on any day of the week, followed by Sundays being proclaimed as a day of rest in 1800. This

Napoleon famously depicted crossing the Apls by Jacques-Louis David

The first distribution of the Legion of Honor

abolition of the revolutionary calendar led to a unified France that ultimately ended the prevalent religious schism. The religious reforms enabled freedom of worship and granted religious toleration, which aligned with the revolutionary principles, thus securing further support for Napoleon, as he was perceived in a heroic light by the people. Overall, even though the somewhat enlightened religious reforms furthered amalgame and ralliement and provided Napoleon with more control over the Catholic Church, they largely benefited the people and upheld revolutionary principal. Therefore, the revolutionary principles proved to be more important in consolidating Napoleon’s power, as he gained an immense amount of support and brought peace and stability to France.

Napoleon’s religious reforms, proved to enhance his support and elevate his authority over the Catholic Church

As previously mentioned, personal ambition was more important than revolutionary principles in aiding Napoleon’s consolidation of power. The refined education and social reforms proved to grant Napoleon the loyalty of the people, further bolstering his support. In reality, the education reforms provided France with an obedient and well-trained set of officials, who would uphold the Napoleonic regime. This consolidated

Napoleon’s power, as it meant that the government were in a position to obtain direct control over the whole system itself. To implement this, 45 lycées were opened from 1802 for boys largely from the middle classes, with an objective to to establish loyalty and respect from a young age. Moreover, the lessons in the lycées were often planned centrally, and teachings were dictated in accordance with the needs and demands of the government. This, again, consolidated Napoleon’s power as he could effectively indoctrinate the young and preserve the Napoleonic regime. Napoleon cemented his power even further by the establishment of the Legion of Honour, which not only created a meritocracy but also ensured that the Granite en Masses could essentially be part of a hierarchy. This strengthened Napoleon’s power as it gained a group of able men who helped further Napoleon’s authority and support him. 15,000 out of 32,000 awards were given to the military, so again, Napoleon had great power in the army and control over its appointment of leaders. However, many aspects of the somewhat authoritarian educational and

social reforms appeared to be enlightened and benefit the people. The presence of revolutionary principles is evident in the fact that Napoleon had 300 schools established with a common curriculum, to aid the improvement of living standards. He also allowed church schools to educate, which upheld the idea of religious toleration and ensured that Catholicism was recognised as the main religion in France. Overall, there was a more meritocratic system, which granted greater social mobility. In summary, Napoleon was able to gain more power and support through his education and social reforms, even though these contained aspects of revolutionary principles; his personal ambition here (to possess control over the entire system), proved to be more important in consolidating his power.

To conclude, personal ambition was more important in consolidating Napoleon’s power than revolutionary principles, as it furthered his policies of amalgame and ralliement and also ensured that Napoleon could create the illusion that he was an enlightened autocrat, when in reality he established a sham democracy and method of control. This effectively prevented the existence of any major opposition, and meant that Napoleon had a system that supported him and upheld his ideals.

In January of this year I, along with 15 lower sixth students, travelled to Poland to further our education on the horrors of the Holocaust. The trip was a part of a wider project, run by Mrs Butler, in conjunction with the Holocaust Educational Trust, which aimed to spread awareness of the genocide exercised by the Nazis in the 20th Century. The main reason for our trip was to visit the Auschwitz camps – both Auschwitz I and Auschwitz Birkenau. This unique experience was an opportunity I could not pass up. The actions of the Nazis and their collaborators in the Second World War has always been an interest of mine, and experiencing a site of mass murder has certainly enhanced my perspective of what occurred as a result of Nazi conditioning all over Eastern Europe, and particularly in the Polish town of Oswiecim.

Upon arrival, it quickly became apparent why the Nazis had strategically selected the location of Auschwitz. A mere hour west of Kraków lies the unassuming town of Oswiecim. The town was at the confluence of the main railway routes of the Third Reich and was conveniently surrounded by forests and marshes, which reduced the dangers of prisoners escaping, enemy surveillance, and attack. The establishment of Auschwitz meant murder became systematic. With the implementation of gas chambers and mass shootings in surrounding forests, the murder of millions of Jews (over 1 million at Auschwitz alone) became more efficient, cheaper, and eventually occurred on an industrial scale.

Having arrived in Oswiecim, the atmosphere immediately changed as it quickly became apparent what had occurred in this seemingly ordinary town. We visited the site of the Great Synagogue to initiate our visit and understand Jewish history in Oswiecim. Following this, we visited Auschwitz I. This camp was constructed to provide a supply of labourers for deployment in SS-owned enterprises, and to serve as a site to murder thousands of innocent people. Having arrived at the camp, we met our tour guide, Patricia, and began our tour. That morning, we learnt first-hand of the experiences that the prisoners were put through. The Jewish experience in Auschwitz was conveyed by a series of exhibitions, including a harrowing

A Trip To Auschwitz

Lower Sixth Camilla Cregeen

display of the suitcases left behind, a vase of remaining ashes, and displays filled with the victims' shoes – last seen by their owners outside a gas chamber. Perhaps the display that was the most shocking to me was that of the prisoner’s hair. An entire room was dedicated to housing the hair, shaved from the victims to completely strip them of their identity upon arrival. The exhibition spanned the entire room and was a shocking reminder of the individual human lives lost in this genocide. However, these displays only provided a snippet of the Nazis antisemitic crimes, as they disposed of the majority of evidence when the danger of liberation got closer. That said, they still provided an invaluable insight.

Walking through a gas chamber was also a distressing experience. Located immediately next door to the chamber, was the house where the Camp Commandant, Rudolph Hoss, lived with his wife and five children. Mere paces from the family home, was the chamber, standing as it did 80 years ago. Walking through the structure brought afflicting feelings. We looked up to see holes in the ceiling, where gas canisters were emptied on the unaware victims, who were simply told they were having a shower after their long journey. The Nazis even went to such lengths as to add false shower heads. In these chambers, the Nazis could kill up to 800 people in just half an hour, making their execution of the Final Solution disturbingly efficient.

Auschwitz Birkenau was very different to the first camp. Immediately we were shocked by the normality of the surroundings of the death camp. This site of genocide lay a few hundred meters away from a main road and was a painful reminder of how life goes on around such horrors. The camp consisted of a series of barracks and gas chambers, however, the majority of these had been burnt down when the Soviet line got closer to the camp. When news of this hit, the Nazis worked to rapidly destroy any evidence of the horrors they had been executing. Birkenau also contained crucial

machinery of mass extermination, to fulfil its sole purpose of murdering as many prisoners as possible. Walking around the camp, there was certainly an eerie atmosphere. Despite there being hundreds of people on tours, conversations were minimal as tourists were shocked beyond words by the sinister systems of the Nazis.

In addition to our invaluable trip to the camps, as part of the project, we were lucky enough to hear first-hand accounts from two women who survived the holocaust. Having now been to Auschwitz, I have been able to put these testimonies into perspective and my knowledge has certainly grown since beginning this project; I now feel the importance of preventing modern day genocides. Since the holocaust, genocides have continued to occur in Cambodia, Bosnia, and Darfur to name a few. Despite the increasing awareness and education surrounding the holocaust, humanity has not seemed to learn its lesson; since 1945, 20 million people have died in genocides all around the world. This is clear evidence that further action must be taken. As a part of this, if given the opportunity, I would urge you to visit Auschwitz, as not only has it enhanced my knowledge of this devastating genocide, but it has also changed my perspective on how we live our lives and how much work needs to be done in third world countries, to prevent such horrors reoccurring.

All Doom And Gloom? A Reflection On The Wasteland By T.S. Eliot

Violet Moffat

Fifth Year

Since its publication in 1922, The Wasteland has been studied, celebrated, and critiqued for its fragmented images and descriptions of a post-World War One society, portraying the disillusionment of a whole generation. The American-English poet, playwright, and literary critic, Thomas Stearns Eliot, drew on varying artistic, literary, and psychological references, helping to create the remarkable 434-line poem that has been hailed as one of the greatest Modernist pieces of literature ever written. Its five sections, calling on writers such as Dante and Shakespeare for inspiration, can reveal truths of the 20th century writer and the terrifyingly intense bleakness of modern life in the wake of The First World War.

This poem has been said to represent perfectly the apathy and futility of the 1920s, ravaged not only by the war, but also the Spanish Influenza, leaving millions dead and countless more scarred. But we should consider if Eliot only suggests that this society was a hopeless wasteland, or

whether he reveals deeper meanings about the present existence of the world. Or maybe, as Eliot puts it, the poem was ‘just a piece of rhythmical grumbling’.

One thing that has caused The Wasteland to be such a celebrated work of art is its explored concept of the fragmented identity. Eliot sought to challenge the complacency of the 19th century Romantic poets, such as Wordsworth, who presented a comfortable sense of self within their poems. Eliot, however, displeased with the comfortable certainties of Romanticism, did not use one individual speaker, rather using a Modernist array of fragmented images and voices.

In Part I of The Wasteland, The Burial of the Dead, Eliot makes a political reference in German about ‘Russin’ (Russia), ‘Litauen’ (Lithuania), and ‘Deutsch’ (Germany). Following the end of the war, Russia, Lithuania, and Germany slowly lost their ground to a mutual alliance. Through this, it is a possibility that Eliot was suggesting a

breakdown of modern society, perhaps even a sense of alienation from one another. The concept of alienation is certainly reinforced by the use of a foreign language, which Eliot distributes throughout his piece. This creates an individual form of isolation for the reader.

Something that makes Eliot’s use of fragmented images particularly interesting is that, whilst there is not one definitive speaker, the various disjointed images all draw on a similar idea: a mechanical life, devoid of meaning. Through this, Eliot also challenges the familiarity of the reader. For example, in The Burial of the Dead, he begins with the infamous line, ‘April is the cruellest month’. This image immediately challenges the common literary trope of spring breeding new life and joy. Eliot challenges the reader’s perception of normality, and their very understanding of literature. This invites the reader to work harder to engage with the poem, leaving them open to new perceptions and ideas.

Whilst Eliot may present an intimate form of disconnection from the reader and their understanding of literature, this is not to say that he intended for the reader to be disconnected from The Wasteland itself. He uses varying images of time, describing an ‘hour’ and ‘a year ago’. However, within this jagged sense of time, the reader must find their own order, creating an intimate understanding of the piece.

We know how famous The Wasteland is for its many disjointed and disconnected depictions, leaping from famous queens to the streets of the East-End of London, however, arguably one of Eliot’s most fascinating ideas that he chose to explore, is the concept of death. Indeed, mortality unites all spectra of history and culture, across all beliefs and societies.

To understand one of the reasons why death is so central to our comprehension of the text, however, we must consider its wider social context. The world of the 1910s and 1920s had never seen such widespread suffering, death, and destruction. Is it surprising that so many felt trapped in a godless, futile existence? It, therefore, is no surprise that Eliot would choose to comment on it. The poem’s first literary reference includes an extract from Petronius Arbiter’s Satyricon, where the mythological character, Sybil, is granted eternal life, yet crucially, she is not granted eternal youth. She sits rotting in her own physical wasteland, and she says, ‘I want to die’. For Sybil, her only chance of escape, and her only chance of peace, is death. It is possible that Eliot uses this reference as a symbol of the metaphorical prisoners of his poem.

Something that critics question when studying Eliot’s piece, is whether he presents death as desirable. In Part II of the poem, A Game of Chess, Eliot repeats the word ‘Goodnight’, and develops it into ‘Goonight’. This is a possible reference to Shakespeare’s Hamlet, where Ophelia spoke this after going mad and before drowning herself. Through this literary reference, Eliot likens the madness of Ophelia to the dull and almost absurd reality of the 20th century. In this context, Eliot presents death to be desirable. Death presents a hope of spiritual rebirth, or at least an end to the apathetical existence, in which the inhabitants of The Wasteland find themselves.

What, however, can we say about the involvement of Eliot’s personal life as an influence for his exploration of mortality within The Wasteland? In 1915, Eliot

married Vivien Haigh-Wood. Described as a vivacious woman, she suffered from both physical and mental illnesses throughout her life. This led to a strained relationship between the pair, which was made more severe by the fact that Eliot was believed to have suffered from bipolar disorder. Eliot even said himself that the nature of their relationship bred the intensity that we find in this poem. He said, ‘To her, the marriage brought no happiness to me, it brought the state of mind out of which came The Wasteland’.

The nature of their relationship bred the intensity that we find in this poem.

The lack of what we may perceive to be normality between the pair, may help to explain a hyper awareness of mortality between individuals within The Wasteland. This is exemplified by Lil in A Game of Chess, whose discussion about pleasing her husband is constantly interjected with the sentence, ‘HURRY UP PLEASE ITS TIME’. This continual interruption serves as a reminder of the fleeting nature of her role within her own marriage, as she grows older, time runs out, and the desire between herself and her husband lessens.

Eliot’s different focuses on women throughout his poem, along with the development of feminist theory over the last century, has caused many critics to discuss his exploration of lust and sex within the poem. This includes a possible social commentary on the role of sexual desire, and particularly the place of women within this, in a modern world.

In A Game of Chess, Eliot talks of ‘The change of Philomel’, alluding to the tale in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, where the character of Philomela was raped by her brother-in-law, Tireus. He then cut off her tongue, so that she could not speak of his grievous crime. The gods took pity on her,

turning her into a nightingale. But Eliot comments that while she sings with her ‘inviolable voice’, her songs fall on ‘dirty ears’. This could be not only a physical representation of the prevalence of sexual violence within modern society, but also a symbol of the silencing of women. We can never be sure of exactly what Eliot’s intention was with this reference. Does it make The Wasteland a feminist poem? Or is it just a comment on the place of mindless sex within the 20th century? The alarming image of the painting of this story, sitting above the ‘antique mantel’, seems to reinforce this interpretation. It sits as a vigil over the inhabitants of The Wasteland, a constant reminder of the reality of inchoate relationships, and the futility of trying to renew them into meaningful relationships.

Indeed, one of Eliot’s most famous descriptions of contemporary sex falls within part III of the poem, The Fire Sermon. Viewed through the eyes of the Ancient Prophet, Tiresias, a ‘typist’ encounters a ‘carbuncular’ man who ‘assaults’ her and leaves her with a ‘patronising kiss’. This image, interpreted as one of rape, is a distressing symbol of the violent nature of sexual desire. The lack of naming of the ‘typist’ or ‘man’ indicates a wider representation of society, and the reality that we are all vulnerable to the gruesome consequences of lust, in replace of meaningful love. Even the ‘kiss’, a symbol of romance and intimacy, has become ‘patronising’, distorted, and empty. Further, it seems interesting that Eliot would choose Tiresias to describe this encounter, as he

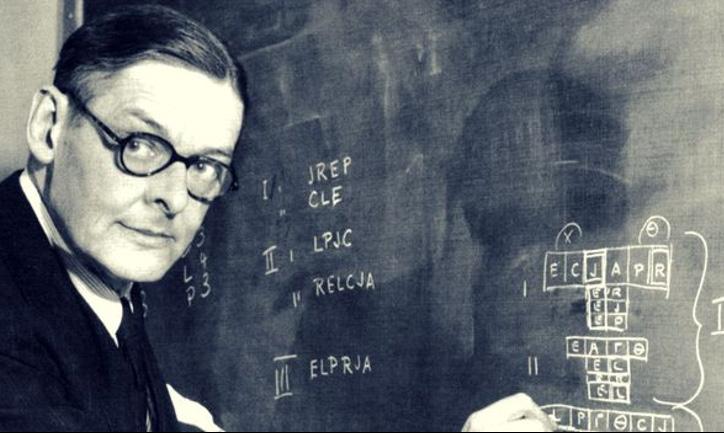

T.S. Eliot

is eclectic, he observes, yet takes no action. If this is a strategic effort made by Eliot, it signifies the powerlessness of renewing meaningful relationships. Lustful desire, and the despair that it leads to, has become entrenched in the modern world.

Eliot was very transparent in the inspiration he found for his works. He was influenced by the poems of the 19th century French poet, Charles Baudelaire, in some of his earlier pieces. However, later in life, he called upon the works of the 17th century metaphysical poet, John Donne, who we may find a particular inspiration for The Wasteland.

It was not only Eliot who found a deep fascination with Donne’s poetry, but also many other modernist writers. Donne was renowned for, as the Critical History of English Poetry puts it, ‘his harshness… intellectual energy, wit, and daring similitudes’. The almost radical remarks found in his poems were welcomed as a contrast to the ‘smoothness and simplicity’ of the Romantics. Donne wittily and philosophically explored the concept of physicality and spirituality. This may help us to understand some of Eliot’s descriptions of sexual encounters as being purely physical and thoughtless.

Arguably, one of Donne’s most powerful explorations of physicality and spirituality falls within his 1617 poem, A Nocturnal upon St. Lucy’s Day. This is a piece that emphasises the lack of mysticism in a physical world defined by temporary, spiritually empty lust. We may even liken his description of the physical world as

being exhausted and dead, to the context of Eliot’s wasteland.

Interestingly, without the presence of love in the physical world, Donne describes himself to be in a state of absolute nothingness, he is ‘none’ without it. This position of emptiness indicates that there is not an absence of something that will renew or reappear, and one can question whether Eliot draws on this in his poem. Indeed, many of the encounters we find in the poem seem to be hopeless.

However, it also implies that being aware that we are mortal is an important factor within this.

Eliot signifies the powerlessness of renewing meaningful relationships.

We also see the influence of metaphysical poets within The Wasteland in Eliot’s exploration of time. Metaphysical poetry is well-known for its exploration of abstract concepts, such as time. This is often understood as a construct designed by civilisation, and, throughout the poem, its structure and its continuity lose their integrity. This, in itself, could reflect Eliot’s view of his contemporary society.

Where we may see the greatest metaphysical influence on the poem about time is within Eliot’s exploration of the infamous concept, ‘carpe diem’, from the Roman poet, Horace’s Odes, which means ‘seize the day’, or ‘pluck the day’. This, along with the concept, ‘momento mori’ (remember that you are mortal), was an idea that many metaphysical poets commented on and suggests that we should savour and make the most of the present moment.

In Part IV of the poem, Death by Water, Eliot asks the reader to ‘consider Phlebas’, who was once as ‘handsome and tall’ as us. It seems to serve as a reminder of our mortality, that we too, like the Phoenician sailor, will age and die. But this is not necessarily a negative viewpoint; it is perhaps a subtle indication that we should be aware of our mortality, and its fleeting nature, so that we do not fall into the monotonous existence of the inhabitants of The Wasteland.

To express a complex exploration of spirituality and spiritual enlightenment following death, it was not only the metaphysical poets whom Eliot called upon for inspiration, but also Dante, and his 14th century epic poem, The Divine Comedy. In his essay, ‘What Dante means to me’, Eliot explores his relationship with the medieval poet, speaking of how Dante’s poetry was ‘the most persistent and deepest influence on [his] verse’, and this seems to be true when we examine The Wasteland.

Eliot sought to ‘establish a relationship between the medieval inferno and modern life’, within his poetry. Even the epic quality of the poem alludes to The Divine Comedy, a spiritual journey through hell (inferno),

purgatory, and paradise. Placing The Wasteland within this epic context helps us to understand what we may perceive to be its largely sporadic structure. The very name of part I of the poem, The Burial of the Dead, and indeed its content, centres around a dead world and an ‘unreal city’, depicting a society that we may liken to both contemporary and medieval descriptions of hell.

Moving into the middle sections of the poem, such as A Game of Chess and The Fire Sermon, we can compare Eliot’s description of a mundane urban existence, such as the repetitive reproductive cycle of Lil, who’s very being appears to be defined by sexually pleasing her husband, to the inescapable Catholic belief of Purgatory, where souls wait to be spiritually enlightened and taken to heaven.