This year INK celebrates its tenth birthday, and it is once again a wonderful celebration of the students’ academic work. Whether its marriage, monarchy or the multiverse, spiders or Shakespeare, there is something for everyone within these pages. This magazine would not exist without the hard work of the students, and the support of staff in encouraging their efforts, and to them I offer my sincere thanks.

Joel Ireland has two submissions, the first of which won him a certificate of Special Commendation in the Cambridge Centre for Animal Rights Law essay competition. His entry won £250 for the school, which has been spent on books to help students with their applications to law degrees in the future.

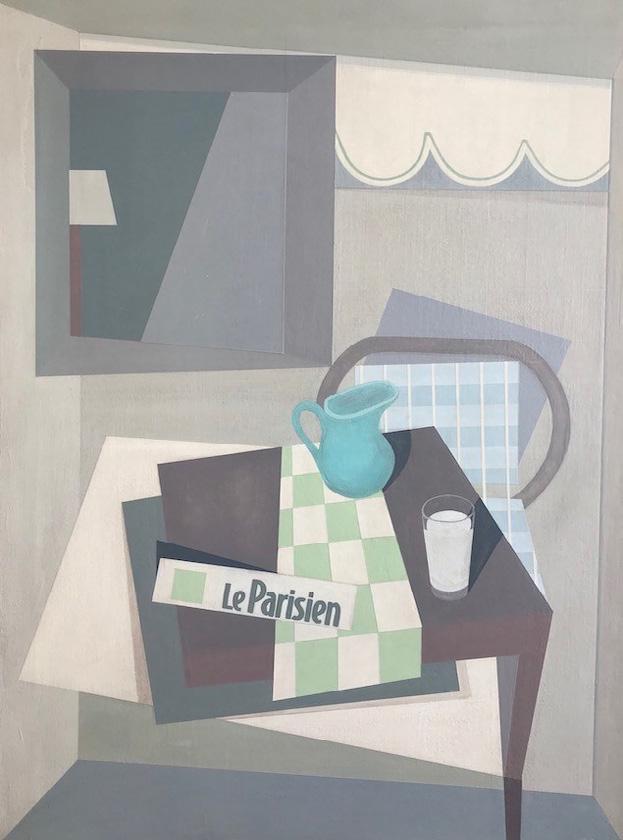

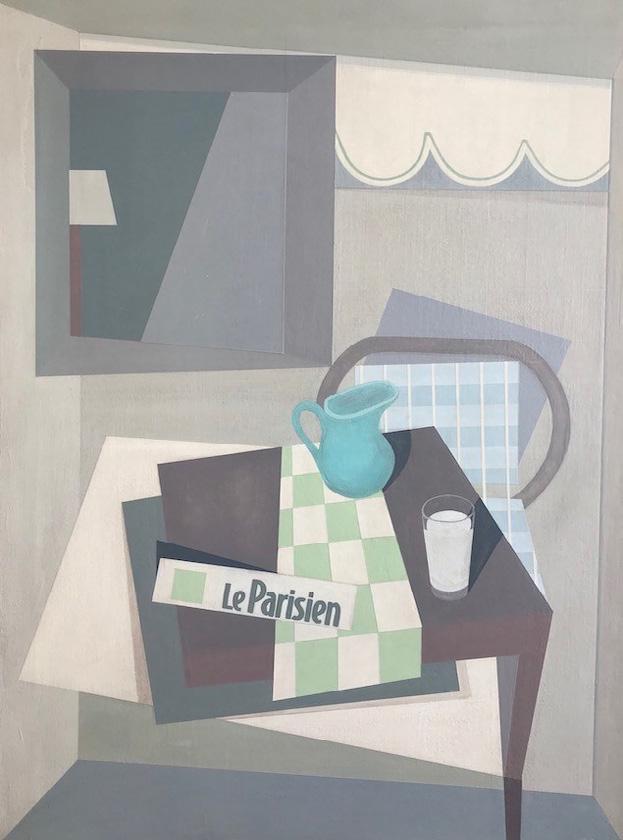

And if after reading the articles you need some time to pause and reflect, perhaps you could do so while enjoying Millie Virtue’s exquisite still life on the front cover.

3-4

5-7

If there is no essential difference between human and other animals, how does this affect the arguments for and against animal rights laws?

Discussion of Act 3 Scene 1 of Hamlet, exploring Shakespeare’s use of language and its dramatic effects

8-9 Should we allow political donations?

10 Murder and the media

Joel Ireland

Julia Nicholls

Adam Smith

Daisy Holroyd

11 Izzy Jupe Izzy Jupe

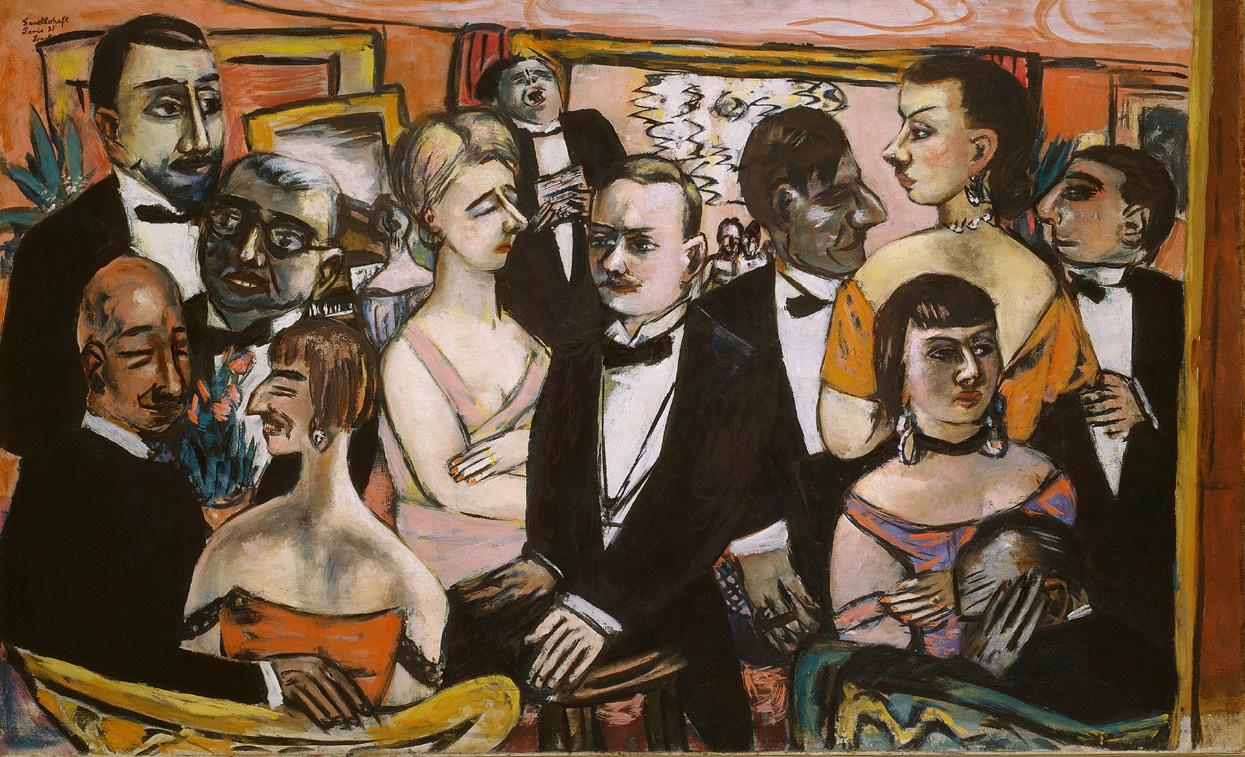

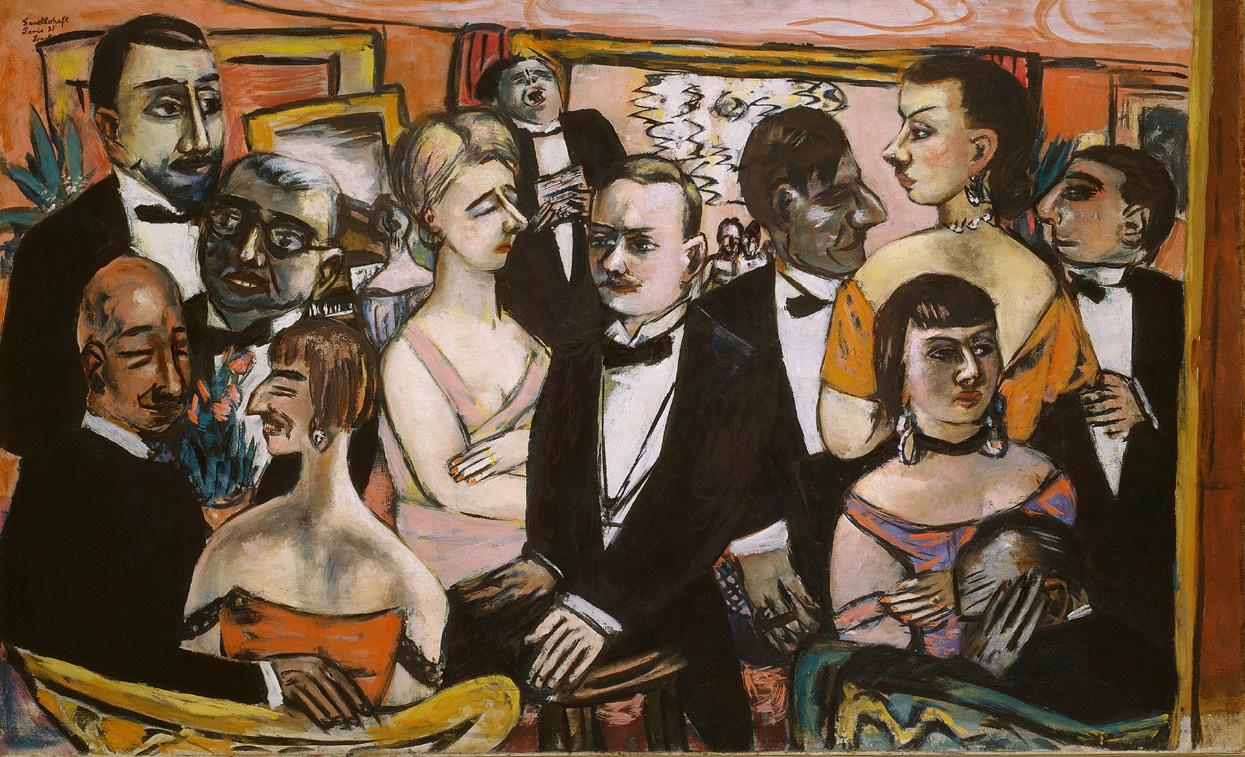

16-20 An Analysis of the Representation of Conflict in Modern Art

21-22 The Red String

23-25

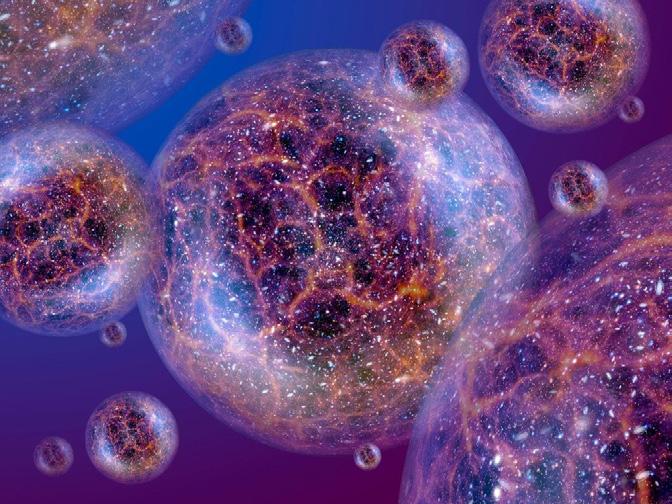

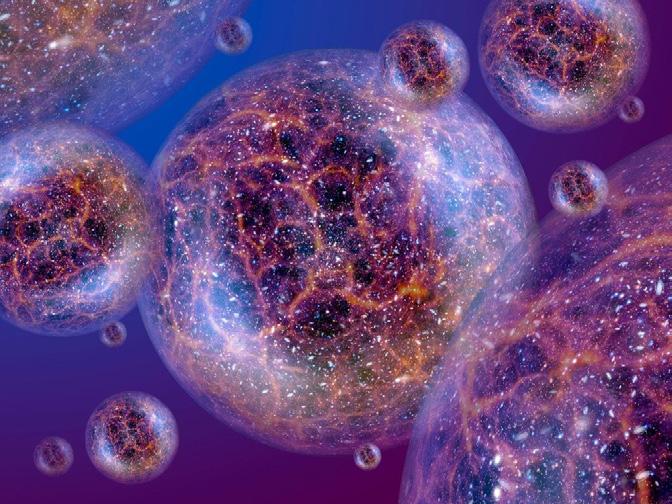

How likely is the multiverse? Would it change anything if (somehow) we came to know the theory was true?

Georgia Humberstone

Beth Roberts

James Restell

26-28 The First World War and The Decline of a Collective European Culture Freddie Dodson

29-33

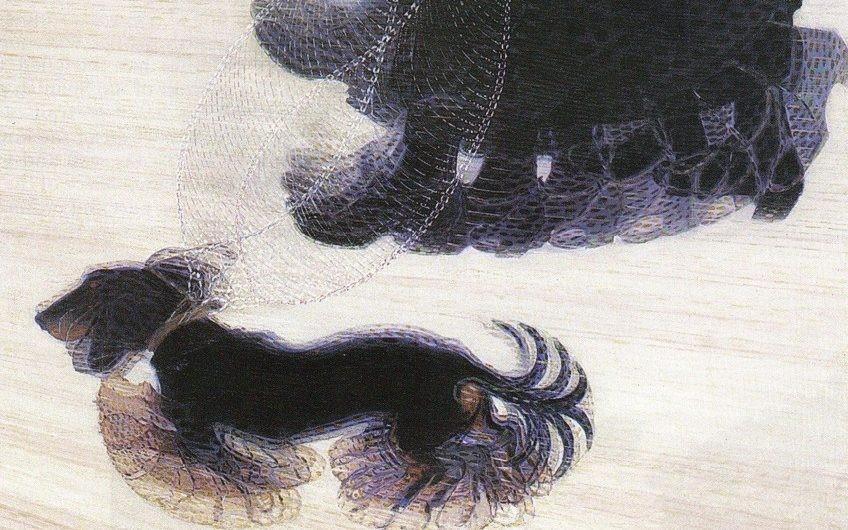

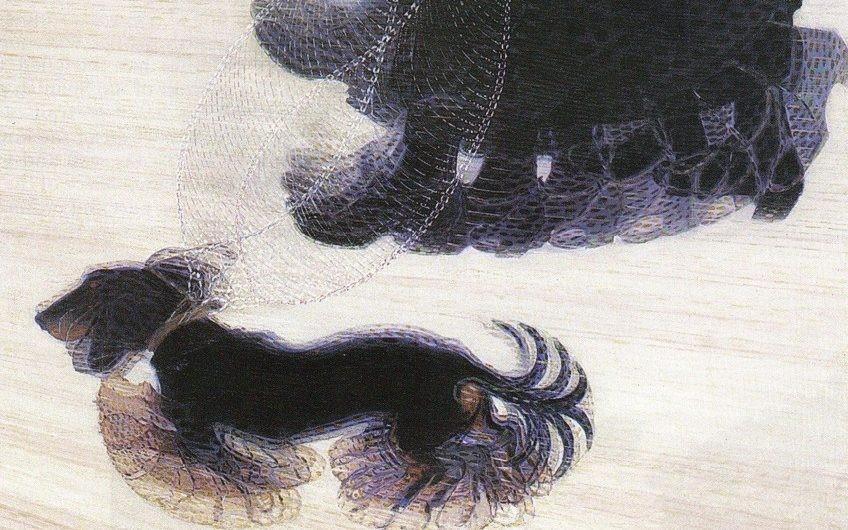

What methods do artists use to capture movement in their work and what does it add to it? Josh Rowley

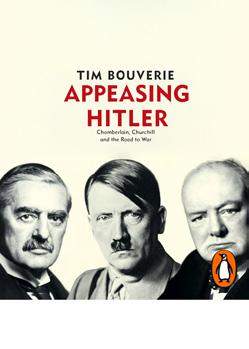

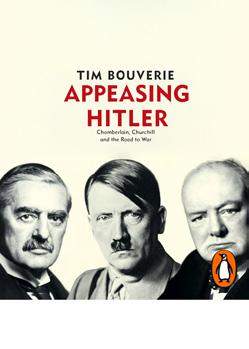

36 To what extent were Hitler and Stalin similar? Josh Taylor

37 Marriage is an outdated concept

38-39 Are politicians dishonest or can we trust them? Josh Wild

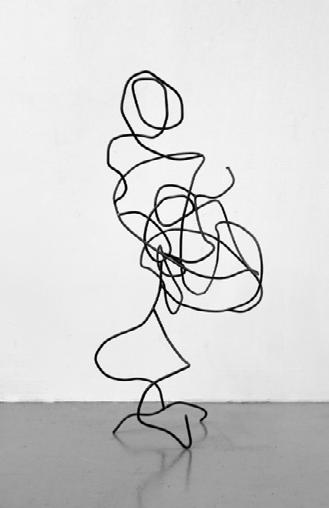

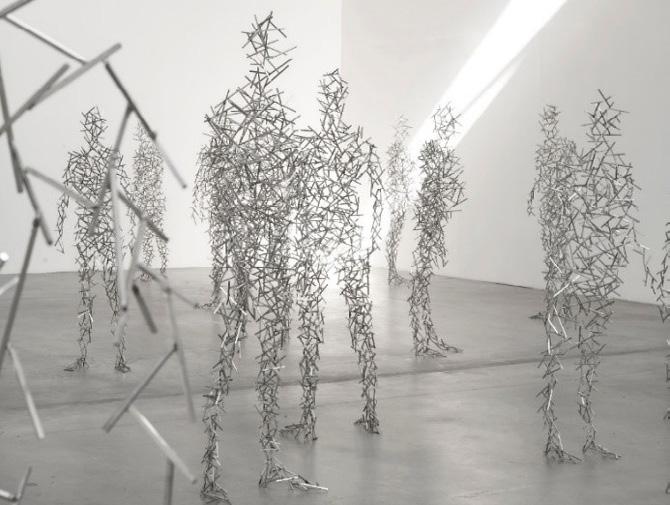

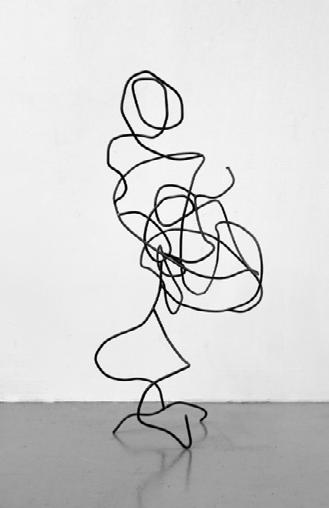

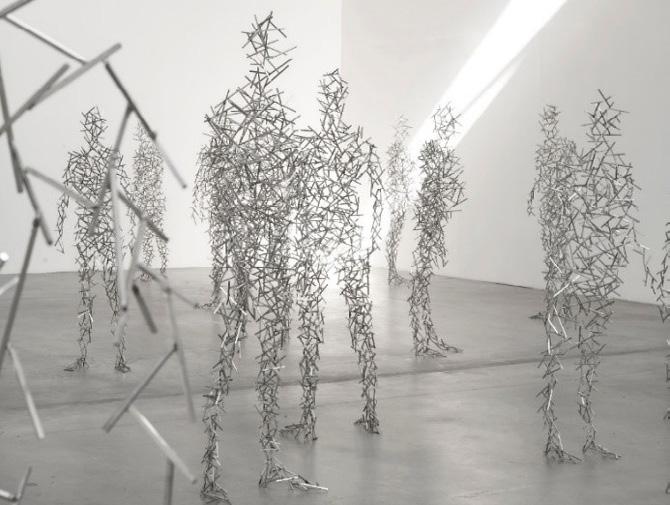

40-42 How have artists used line within sculpture? Natalia Schmitt

43-45 Must we always obey the law?

46 Oh my goodness, I hate spiders

Joel Ireland

Orion O’Connor

What are the environmental costs of current consumer trends, behaviours and purchasing decisions? Tom Dodgson 49 Should the monarchy end when the Queen dies? Ben Dakin

47-48

Evans de Céspedes 51 Shell Shock

Cassidy

William Baker Head of Sixth Form

Cover painting by Millie Virtue: Still life (GCSE)

Rosalind Mitchell

Gabriela

Contents Editorial 2

50 Les glaçons Clara

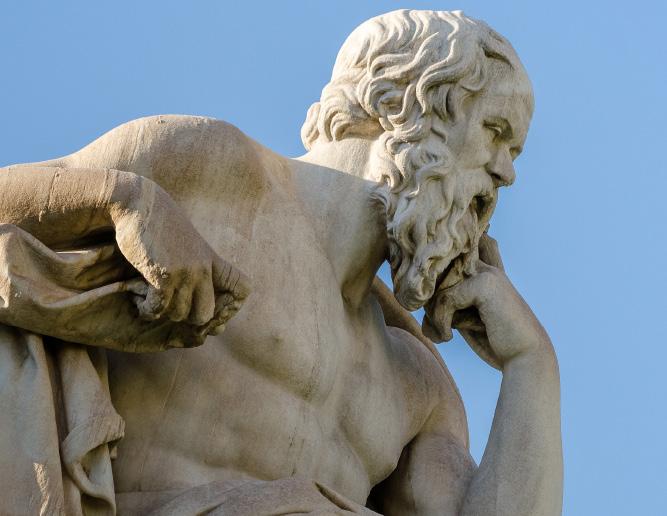

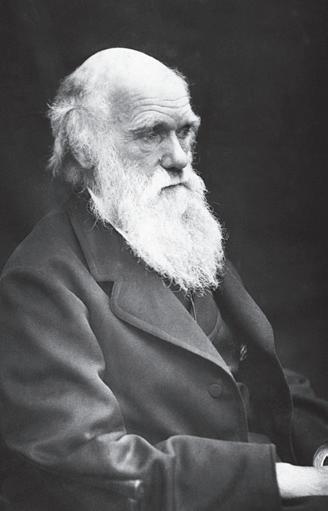

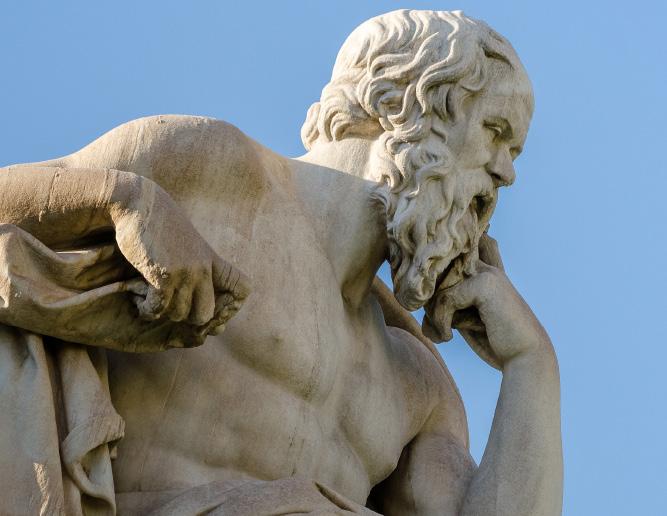

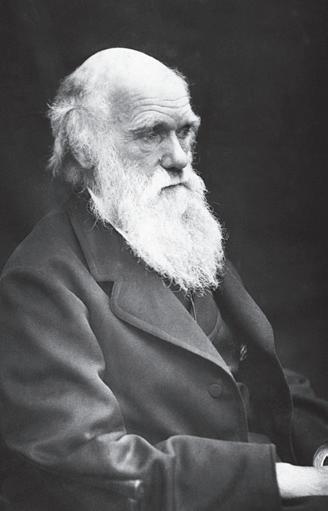

In Darwin’s Theory of Natural Selection, he proclaims that “There is no fundamental difference between man and the higher mammals in their mental faculties”.

(Humane Decisions, 2016) He also advocates that the difference, if any, between humans and non-human animals (animals hereafter) “is one of degree and not of kind”. If this aforesaid comparison holds merit, then it ought to be our moral obligation and responsibility to provide similar rights to animals as the ones established to protect humans. Numerous animals are akin to humans in their capacity to discern by sense and so providing them with legal instruments for the redress of their grievances is justifiable. However, our supposedly superior metacognitive capacities and human nature might be enough of a reason to explain the current moral distinction held between humans and animals and provide an argument against extending animal rights.

Firstly, we need to address what this essay aims to answer. The question being, is it true that biological similarity holds overriding value on the debate of animal rights law? Is biological similarity an adequate reason to grant rights to animals?

Biological similarity can be defined as common traits shared interspecies due to the genetic composition of such beings. Features such as cognitive ability,

fundamental organismic processes and sentience will be characterised as biological similarities. Sentience is dependent on cognitive abilities and environmental analysis, resulting from complex brain activity and for that reason it is classed as a biological trait (Centre for Animal Welfare and Anthrozoology Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Cambridge, 2014).

Biological similarity is a sufficient reason to provide animals with the same rights as humans because if they are alike, we should not treat them differently. Chimpanzees are among our closest living relatives, sharing a common ancestor with humans a mere six to eight million years ago. In 1960, Jane Goodall investigated the behavioural characteristics of wild chimpanzees in Tanzania (Jane Goodall Institute UK, 2023). Studies of chimpanzees like Jane’s have revealed several aspects of human evolution, including tool use and other cultural traits such as hunting and intergroup violence (National Library of Medicine, 2017). If justice demands that like beings be treated alike, it cannot be just to exploit biologically similar animals on the grounds that humans themselves are

not subject to such behaviour. If animals possess the characteristics which we use to define humans, then they should be entitled to equivalent protection under the law. This biological similarity argument is what drove numerous other movements including the civil rights movement of the US, which was a campaign by Black Americans to receive equal protection under the law. They advocated against segregation and proclaimed that such treatment should not be permitted in a just, constitutional society. Therefore, because there is no obvious fundamental difference between humans and higher mammals, we are morally obliged to present such animals with matching laws, as that is what a just society must do (Bryant, 2007).

However, biological similarity might be deemed insufficient in the eyes of the law. There are many flaws with this similarity argument. Whilst our closest relatives, chimpanzees, share several essential human characteristics, this statement is not entirely true for all animals. Furthermore, the caveat that animals do not share enough characteristics to receive equal protection under the law holds merit. Whilst a successful study conducted by Daniel J Povinelli in 1997 proved that chimpanzees

If there is no essential difference between human and other animals, how does this affect the arguments for and against animal rights laws?

[T]here is no obvious evidence of animals engaging in mental time travel which is the ability to foresee future scenarios.

Lower Sixth

Joel Ireland

Jane Goodall

3

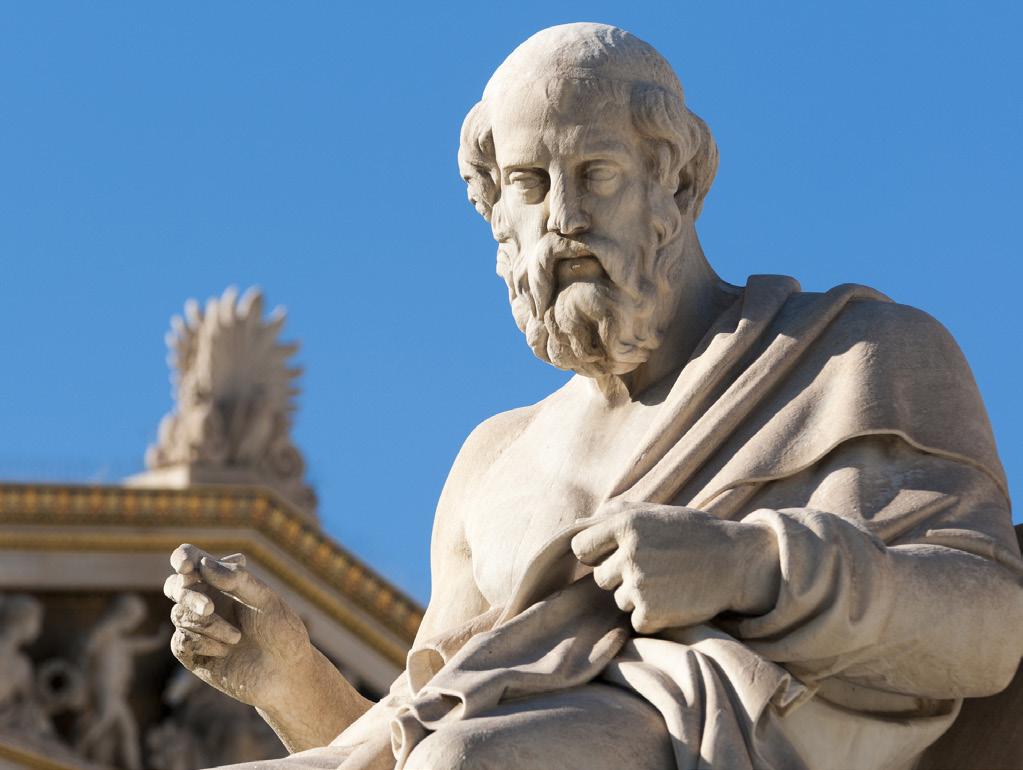

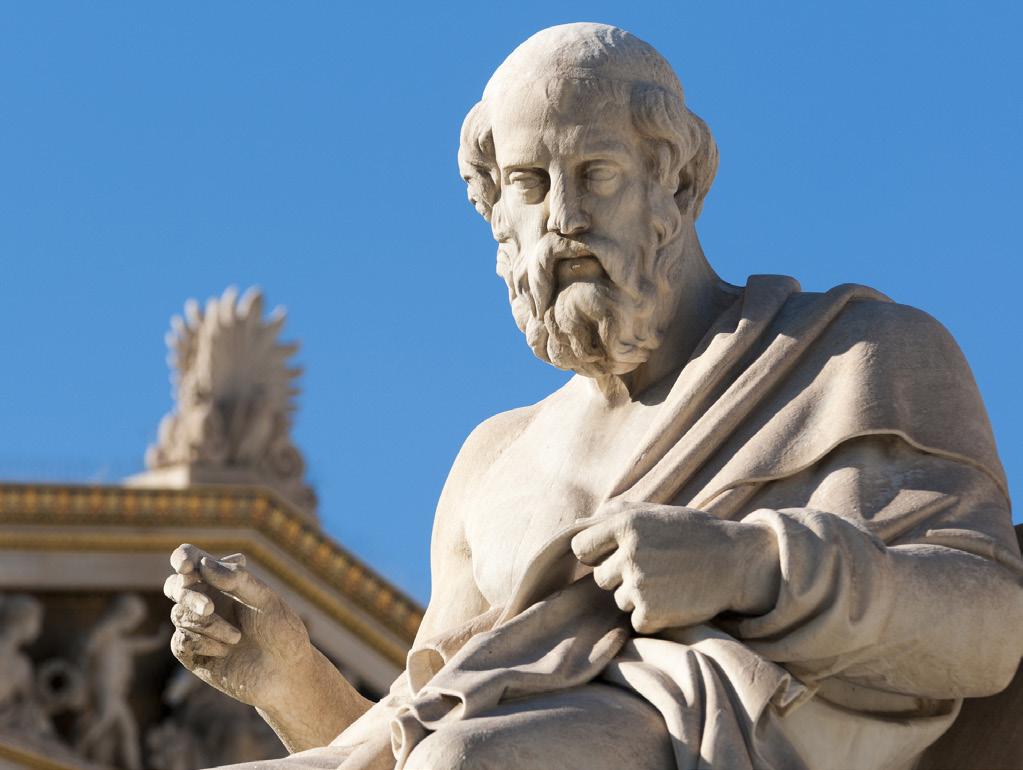

Charles Darwin an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology

exhibited self-awareness traits (Science Direct, 1997), various cognitive abilities which humans display have not yet been demonstrated by animals. For example, there is no obvious evidence of animals engaging in mental time travel which is the ability to foresee future scenarios (Scientific American, 2018). Mental time travel is one of the main reasons why we impose laws in the first place. Because we can see potential future predicaments, we try to prevent these by enacting laws. Aristotle proclaimed that the difference between humans and animals was that humans possessed a “rational soul,” in addition to the “sensitive soul” of animals (The Guardian, 2022). Furthermore, another pitfall of the similarity argument is that it would be impractical to supply rights to animals with the closest biological proximity to humans and not others. Determining whether a certain species exhibits enough similarities to reap the benefit of protection under the law would be injudicious and would create an unmanageable hierarchy in the animal kingdom led by humans. Consequently,

whilst biological similarity has some influence on the debate of animal rights, the similarities might just fall short of equal access to legal protection.

Furthermore, biological similarity must not have such a profound influence on the animal rights debate, since we are already supplying laws protecting animals which are distant from humans. For example, under the Protection of Animals Act of 1911 (The National Archives 2023), it is stated that “If any person cause[s] any unnecessary suffering to any domestic or captive animal [they] shall be liable on summary conviction to imprisonment for a term not exceeding six months or to a fine not exceeding level five on the standard scale”. The act aims to protect any “sufficiently tamed [animal which] serve[s] some purpose for the use of man”. This reveals that rights and laws are issued to animals which possess some use to humans as opposed to being biologically similar.

To conclude, whilst similarity should be sufficient grounds for granting rights to

animals, this advocation itself might not be the problem. The problem might rest in the social construct of society, a common misconception being that animals are not sentient beings and cannot experience suffering and pain. There has been an absence of necessity in petitioning new animal rights laws. It was only recently that the law recognised certain animals as sentient. The Animal Welfare (Sentience) Act 2022 (The National Archives, 2023) is an example which states that any vertebrate other than homo sapiens such as any cephalopod mollusc, and any decapod crustacean will be formally recognised as sentient entities by law as of 2022 (Gov. uk, 2022). Hence, biological similarity is an adequate reason for providing such animals with equal rights. Regrettably though, in the society in which we live, reflective of human nature, if such animals do not bear sufficient value to humans, society will not prioritise or feel the need to provide them with mirrored rights. Moreover, it would create a hierarchical society. Animals which are more closely related to humans would receive more extensive rights than others and it would create a complex unjust system of laws impossible to enforce.

It was only recently that the law recognised certain animals as sentient.

4

The United Kingdom was the first country in the world to implement laws protecting animals as early as 1822

Discussion of Act 3 Scene 1 of Hamlet, exploring Shakespeare’s use of language and its dramatic effects

Julia Nicholls

Lower Sixth

be that Hamlet is actually aware that he is being watched by the king and Polonius and chooses to lie in order to confound Polonius’ doubts about his mad love for Ophelia.

Despite Ophelia’s seemingly natural reticence and her quiet demeanour, she seems to assert herself against Hamlet’s cutting remarks towards the start of the scene. Following Hamlet’s lie that he ‘never gave…aught’, Ophelia replies by saying ‘you know right well you did’, suggesting that she is finally starting to stand up for herself. Similarly, when Ophelia describes how ‘rich gifts wax poor when givers prove unkind’, it seems as if she is retaliating against Hamlet’s contempt and making a dig at his animosity once and for all.

built up in the exchange between Hamlet and Ophelia, making the audience wary of what might happen next.

In this passage, Hamlet and Ophelia find themselves in an increasingly heated exchange whilst being spied upon by King Claudius and Polonius, Ophelia’s father. The overall feeling conveyed by the passage is one of anger and bitterness, making it somewhat painful for the audience to witness. There is also a significant focus on sex, forced mainly by Hamlet, which not only seems inappropriate but also poses the key question of whether or not his supposed madness is actually real.

At the start of the passage, when Hamlet first sees Ophelia on stage, he says ‘soft you now’, telling her to be quiet and to wait a moment. This implies that he is impatient and suggests a certain level of disrespect as he does not even bother to greet her politely.

Likewise, when he says, ‘I humbly thank you, well’, it is presented as sarcastic to the audience and his lack of sincerity is highlighted.

Following Ophelia’s request to ‘redeliver’ the ‘remembrances’ that Hamlet once sent to her, Hamlet replies by saying that ‘no’, he ‘never gave… aught’, which is a lie. This could reflect his potentially hurt pride, since Ophelia has refused his gifts to her under her father’s orders and so he could be lying simply to protect his ego and conceal his humiliation. However, a different interpretation could

Despite this, Hamlet appears to regain control of the conversation as he shifts the register from Ophelia’s couplet to prose, allowing him the opportunity to question her more closely through a change into rapid dialogue. His response to her rebuttal seems rather strange, and could make the audience uneasy, as he exclaims ‘Ha! Ha! Are you honest?’ in what could be perceived as an aggressive tone. It signifies not only a change in register, but also a change in the subject of the conversation, as Hamlet suddenly starts analysing Ophelia’s beauty and chastity. Perhaps the reason for this could be a continuation of Hamlet’s hurt pride, along with internal surprise at her assertive replies to his remarks, or contrastingly he could be asking her the question because he knows that they are being spied upon, and thus wishes to aim the question at Polonius, who would be interested in the matter of his daughter’s virginity. Furthermore, this sudden outburst could affirm suspicions of his madness to the onlookers, although ironically the audience knows that this could simply be the antic disposition being acted upon. However, it must be made clear that whether or not Hamlet knows of the espionage in this scene remains an unknown fact to the audience. This uncertainty increases the tension already

Whatever the reason for Hamlet’s eruption, it clearly throws Ophelia off guard as well, as her responses are short and seem to lack the confidence and assertion that she possessed not long ago. This results in stichomythia, in which Ophelia cannot seem to answer Hamlet’s questions for she is too shocked, only managing to utter a simple ‘my lord’ and ‘what means your lordship?’ in reply. Hamlet turns the conversation into a scrutiny of Ophelia’s fairness and honesty, saying ‘that if you be honest and fair you should admit no discourse to your beauty’. Essentially, he is repeating the conventional belief of the Shakespearean time, which is that beauty and chastity are seemingly incompatible and difficult to reconcile. It suggests that beauty is a potential threat to chastity, which in itself portrays the concept of virginity as something sacred and unbreakable. However, in today’s society, we can see how misogynistic this view is, as it limits women’s sexual liberty and independence.

In Ophelia’s response to this personal attack on the matter of her chastity, the audience can see that she attempts to move the focus away from herself by using abstract personifications to take meaning away from the individual and turn it into a philosophical debate. The capitalisation used when Ophelia says, ‘could Beauty, my lord, have better commerce than with Honesty?’ shows how she is personifying these abstract qualities to make them more generalised. However, Hamlet seems to somewhat ignore Ophelia’s attempts to reconcile the conversation, and instead he continues describing ‘the power of Beauty’ to ‘transform Honesty…to a bawd’, showing his cynicism of love and the deep-rooted societal misogyny he adds to, along with imagery of disease and sexual corruption. This discourse is concluded when Hamlet tells Ophelia ‘I did love you once’ in a monosyllabic sentence, implying that his strong cynicism of love has led him to not even know what it means anymore. However, this sentence is short and, particularly when compared to the longwinded points he makes before it, could be

[T]his sudden outburst could affirm suspicions of his madness to the onlookers.

5

interpreted as the only candid thing Hamlet has said to Ophelia so far, suggesting a certain vulnerability in love, and bringing the philosophical element back round to a more personal sentiment once again.

Nevertheless, the moment is short-lived, as Hamlet proceeds to tell Ophelia that she ‘should not have believed’ the fact that he once loved her. This is ironic, as it echoes Polonius’ earlier advice to his daughter (that she should ‘not believe his vows’), and it is also strange, as Hamlet’s words to Ophelia are contradicting each other and he seems to be robbing language of its meaning. His manipulation of words continues as he says, ‘I loved you not,’ which comes as such a stark contrast to what he has just admitted (‘I did love you once’), that it suggests an element of indecision and internal conflict which he could be unaware of if his antic disposition has developed into real madness.

This supposed madness appears to escalate as Hamlet proclaims, ‘get thee to a nunnery!’, after a short and rather dejected interjection from Ophelia that she ‘was the more deceived’ by Hamlet. The possible ambiguity arising from the double meaning of the word ‘nunnery’ could have different implications in the way that the exclamation is interpreted by the audience. On the one hand, and in its usual definition, Hamlet could be trying to preserve Ophelia’s beauty by deterring her from losing her chastity. However, as ‘nunnery’ can also mean a brothel in the slang sense, there is a small chance that Hamlet could be saying this in order to get her to lose her virginity and thus ruin her natural beauty in a brothel (perhaps out of spite and bitter vengeance as she rejected him before). This seems unlikely though, as Hamlet’s whole case up until this point has been based off of the supposed need for Ophelia to guard her chastity. Either way, Hamlet’s repetition and his persistence in the matter of discussing chastity and nunneries so openly with Ophelia suggests a potentially disturbing obsession or preoccupation with sex. And, particularly in the low chance that the latter interpretation was to be correct, there could also be a suggestion that Hamlet’s antic disposition is causing him to act like this.

The audience’s attention is shortly brought back to the matter of Hamlet’s suspicion, regarding espionage, when he asks Ophelia ‘where’s your father?’ at the end of his discourse. This sudden change of subject, once again, indicates Hamlet’s erratic mind which could be a further cause of his antic disposition. More importantly, the abrupt reference to Polonius seems to be rather pointed, almost as if he knows he is being watched and wants the spies to know and hear him as well. In this way, when Hamlet says to Ophelia ‘let the doors be shut upon him that he may play the fool nowhere but in’s own house’ the audience sees it as such a decided reference to Polonius, as he is clearly heavily insulting the man, that it suggests Hamlet must know that he is being watched. His insolence is further highlighted when he abruptly tells Ophelia ‘farewell’, which the audience could perceive as being a very blunt and arrogant thing for him to say when he has just ordered her to go away to a nunnery.

However, despite Hamlet’s impoliteness, Ophelia seems to remain as compassionate and gentle as ever, proclaiming ‘o help him, you sweet heavens!’ as an aside. Here she understandably assumes that Hamlet is genuinely mad, yet in doing so she still holds an incredible amount of empathy for someone who has treated her so badly. Later she also says ‘heavenly powers restore

him’ in an act of sympathy, despite the fact that beforehand he insults not only her but the whole female population too. In saying ‘if thou wilt needs marry, marry a fool, for wise men know well enough what monsters you make of them,’ Hamlet shifts from his specific castigation of Ophelia to attacking women in general, which highlights both his cynicism of love once again and the fact that he feels betrayed or let down by his mother. Additionally, his reference to marrying ‘a fool’ links back to his recent insult against Polonius, suggesting that he believes stupidity runs in the family and jumps between generations. Parallels could also be drawn to Freud’s theory of the Oedipus Complex, in which young children are said to desire sexual involvement with the parent of the opposite sex during their Phallic stage of development. This concept also suggests that, when grown up, heterosexual women often tend to marry those who resemble their fathers, while the reverse is said to be true for men. In this way, Hamlet could be suggesting that, in order to agree with this theory, Ophelia should marry a fool, just as her father is one. Equally, this would suggest that Hamlet sees himself as an example of one of the ‘wise men’ that he refers to in his comparison, implying that he has a strong superiority complex and wrongly views himself as better than both women and other men.

The repetition of ‘farewell,’ interspersed with long ramblings from Hamlet, implies that he keeps turning to go before thinking of something further to say; this emphasises his volatile manner and suggests that his bitterness for Ophelia is far-reaching, as

[M]uch of what Hamlet says is inherently misogynistic and reflects a deeprooted cynicism of love and women in general.

6

David Tennant as Hamlet in Gregory Dornan’s 2008 RSC production of Hamlet © Ellie Kurttz @ RSC

he cannot seem to stop insulting her. Even after all this, Ophelia stays calm and civil, only praying that the ‘heavenly powers restore him’. However, all that this sympathy and submission from Ophelia manages to do is to simply inspire Hamlet to continue insulting her, spurring him on in his attack of women. He goes on to slander the way women look and act, with reference to a woman’s ‘face’ and ‘jig’ as being ‘wanton’. He also calls off the marriage between himself and Ophelia, claiming that she ‘hath made [him] mad’, which once again raises the question of whether there is any truth behind Hamlet’s antic disposition.

His claim that ‘those that are married already…shall live’ – ‘all but one’ – seems like a very pointed reference to Claudius, suggesting once again that he knows he is being spied upon. It also seems like a rather dangerous thing to say as, if Claudius has any sense at all within him, he should surely be aware that Hamlet is referencing his potential future murder. The passage ends with Hamlet’s repetition of ‘to a nunnery, go!’, which is both ironic and hypocritical as, not only has he said this several times before, but he has also consistently returned to pester Ophelia some more after

she has tried to end the conversation. In some strange way this could almost imply that Hamlet, for all his want to insult and belittle Ophelia, still holds some affection for her and feels hurt by her rejection of him.

Overall, this passage portrays Hamlet as rude and hostile, particularly towards Ophelia, although some might say that her betrayal and rejection of him somewhat justifies his behaviour in response. Regardless of this, it seems clear to the modern audience that much of what Hamlet says is inherently misogynistic and reflects a deep-rooted cynicism of love and women in general (perhaps stemming from his precarious relationship with his mother and her betrayal of his father’s love). Likewise, Hamlet seems to maintain a strong focus on sex throughout the passage, suggesting a somewhat unsettling obsession that keeps on developing and unravelling. It could be argued that Ophelia was wrong to follow her father’s instructions of ignoring Hamlet, and perhaps such behaviour makes her immoral to some extent, but on the other hand she could be seen merely as the victim of an oppressive patriarchy, as both her father and Hamlet seem intent on manipulating her to suit their own selfish needs. These various elements, along with evidence of Hamlet’s antic disposition and his suspicions of espionage, combine to create tension in the passage and reveal the underlining painful nature of this scene.

Patrick Stewart as Claudius in Gregory Dornan’s 2008 RSC production of Hamlet © Ellie Kurttz @ RSC

Patrick Stewart as Claudius in Gregory Dornan’s 2008 RSC production of Hamlet © Ellie Kurttz @ RSC

7

Mariah Gale as Ophelia in Gregory Dornan’s 2008 RSC production of Hamlet © Ellie Kurttz @ RSC

Should we allow political donations?

Adam Smith

Upper Sixth

Introduction

It is clear that in some countries, and their political systems, political donations are integral in allowing the candidates to run their campaigns effectively. For instance, in 2019, Joe Biden’s presidential campaign raised $6.3 million dollars in the first 24 hours, amassing to a remarkable $1.6 billion. In order to win his presidential battle, Biden spent 99% of these funds. Donations therefore are a critical factor, especially within the American system, in allowing candidates to run campaigns, and for the current system to work. However, time and time again, political donations have produced, and perhaps encouraged, corruption and abuse of the political system. They can be argued to lessen the value of an individual’s support and encouraged the idea that money can win elections.

Do Donations Encourage Corruption?

When it comes to explaining the ethical complexities that arise when discussing the value of political donations, it is important to consider the detrimental effect that donations can have upon a system. For example, a government’s legitimacy may come under question if individuals within the government are found to be taking bribes or illegally and immorally spending money. This was especially true for Brazil, who outlawed corporate donations in 2015 amid a corruption scandal in which the country’s president at the time, Dilma Rousseff, was almost driven to impeachment. Under further investigation, it was found that five of the top ten corporate donors in the 2014 elections had employees who held senior executive roles within the party, showing the abuse that had been taking place due to unrestricted political donations as well as the potential damage political donations in general can cause. Therefore, allowing political donations undoubtedly opens the door to corruption and abuse of the political system. Examples such as Brazil are a great example of what Katz and Mair dubbed as a ‘cartel party’, under their ‘Cartel Party Thesis’. This thesis holds the view that political parties increasingly function like cartels, by employing the resources of the state to limit political competition and to ensure their own electoral success. Brazil is a classic example of this particular

idea, considering that, according to the Guardian in 2015, the Worker’s Party treasurer, João Vaccari Neto, was charged with corruption and money laundering, possibly related to illegal campaign donations. In total, Brazil loses 1-4% of its national GDP each year to corruption, equating to around 30 billion reais, or £4.8 billion. In addition to this, in a more wellknown example, the Cash-for-Honours scandal, which occurred in the UK in 2006, is yet another example of how loopholes in how donations are restricted can produce corruption within a political system. This particular scandal resulted in the eventual arrest of the Labour Party’s Lord Levy. Not only did this undermine the legitimate nature of political donations in general, but it can also be argued that it hastened Tony Blair’s resignation as Prime Minister, showing that not only can the abuse of donations affect the whole system, but it can also have a detrimental impact on any and all parties involved.

It is important to note that this is not a problem of the past, one must only look to France in 2018 to see the undemocratic effects that donations are having upon the system. In an examination into the role that money plays in French politics, it was found that private donations represent a much higher funding for right-wing candidates than their left-wing counterparts. On average, right-wing candidates receive an extra €3,400 in private donations. Whilst this does not sound like a big discrepancy, it is important to note that average spending per candidate in an election is only €22,000, showing the immense difference and subsequent inequality, that political donations produce. Further research showed that an extra €8,000 in private donations received by right-wing parties compared to socialist party candidates in legislative elections helps enable them to gain a 1,367 to 2,734 vote advantage. It is clear to see that this

is hugely and unarguably undemocratic and supports the claim that donations can corrupt the legitimacy of elections as candidates can effectively ‘buy’ people’s support, as well as the vote that comes with it.

‘One Euro One Vote’

Arguably, the guiding principle of democracy is that one person gets one vote. In a democratic system, everyone’s vote should be valued equally and hold the same worth, no matter your social standing or wealth. Political donations can undermine this core principle as parties will see potential donors as more important than people who don’t have significant amounts of money to give. For example, in the United States mega donors fuel the rising cost of elections through their donations, with one particular group, Future Forward USA, contributing $151 million, almost 10% of the total money raised, to Joe Biden’s campaign in 2020. Although these donors get the same number of votes as everyone else, they are seen as more valuable to the candidate and so the candidate will be inclined to alter policies to benefit the donor so they can secure the potential donation. A historical example of this is the Labour Party’s continued support of trade unions, by promising to keep unions strong, they can secure the immense funding that unions contribute through membership fees. For example, up until 2014, unions had a system in place, the electoral college system, that allowed them to elect the leader and deputy leader of the party. Unions donated £5 million to the

8

Labour Party in 2019, 93% of the party’s total donations that year. By having a party or candidate reliant on you for a significant amount of their funding, donations grant certain groups, or wealthy individuals, a significant amount of influence over parties and candidates that many people cannot afford, highlighting yet another reason that political donations should be limited and how the value of people’s vote is changing.

Another argument to support the negative impact money can have on politics is by giving significant donations, donors may be given exclusive access to MPs and members of the cabinet. Angus Fraser, who had previously donated around £2.5 million to the Conservatives under David Cameron’s leadership, was given a place on Cameron’s ‘leader’s group’ which gave its members special access to the PM and other ministers. It is important to note that this is not a problem limited to the UK or any one country. An even more striking, and perhaps more relevant example is The National Rifle Association and their personal relationship with many senior politicians, in particular with Senator Mitt Romney. The NRA has donated more money to Senator Romney than any other Republican Senator, amassing to a grand total of $13 million. It surely can be no coincidence that Senator Romney has ferociously and publicly defended gun rights, even accusing president at the time Barack Obama of restricting US citizens of their Second Amendment, the right to keep and bear arms. It is also likely that he spoke at the annual NRA conference in 2012 in St. Louis as a result of these substantial donations. This shows the access the NRA has gained from their donations and how they continue to benefit from them through their lobbying arm, the Institute for Legislative Action. In 2020 the NRA spent around $250 million in donations; this is more than all the country’s gun control support groups put together. This shows the extensive reach

that donations have given them, and how money has been able to buy the extensive influence that may not otherwise have been available to them. This is a strong argument to back the idea that money can distort the value of your support, and to a certain degree, your vote. This, therefore, is another argument that supports the potential ban or regulation of political donations.

Is There an Alternative?

There have been plenty of arguments and campaigns over the years protesting the use of political donations. For example, in 2007, the Phillips Report stated that there “was now a strong case for political parties to be funded through taxation”. This could, however, result in an increase in taxes. However, it would negate many of the negative aspects that political donations can have on a system. For example, in Sweden, public subsidies provide 80-90% of the major parties’ annual revenue and all anonymous political donations are capped at SEK 2,275 (£183). A party’s funding is allocated according to the share of votes in the previous election. Furthermore, funding is not accessible to parties that have received donations from any anonymous donors. This is a legitimate way of ensuring democratic competition between parties, as no party has a significant advantage over the other based on substantial anonymous donations. Australian politician David Tollner has proposed making major political donations illegal, restricting them to no more than $1,000. He argued that “this is the only transparent way of doing it” and that the existing system has become “all too grey and blurry”. Although this sort of system allows some donations, it would mostly wipe out any influence that any groups or individuals may have as a result of significant donations, as they are capped at a very small amount. This could be argued to be a successful alternative as it allows individuals to support their party, and as a consequence of this, encourages political

participation which can be seen as good for the democratic system.

At the extreme end of the spectrum, you could ban political donations entirely. This is what Labour Senator Sam Dastyari in Australia has called for. He claims that this would “even up the playing field” for all parties and would “eliminate the perception and reality that rich donors are able to buy access of influence in politics”. Although this may be true, a total ban is perhaps not a realistic alternative. Elections are expensive, and the cost is only increasing. The current amount that parties receive from public funding sources are frankly not enough to pay for an expensive election campaign. Take the USA as an example of this; the 2020 Presidential Election cost a record $14.4 billion. This is more than double the total cost of the 2016 election and more than three times as much as the 2014 election. It is therefore clear to see that banning political donations entirely is not the solution to the problem regarding abuse of donations. I believe the only way to allow to properly fund elections, whilst avoiding corruption, is to cap donations at a specific amount which isn’t large enough to cause significant sway in an election. This is a system used internationally and has been proven to work.

Conclusion

By altering the way in which we regulate political donations, we can retain the good that political donations provide and eliminate the negative aspects that they can bring. In this essay, I have clearly outlined the drawbacks of political donations, not only their influence on those in power, but how they also affect the voter. They are a way for people to participate in politics, and a way in which people can support those who represent their thoughts and views. By removing them entirely, you are removing a way in which the voter can allow their voice to be heard. It is therefore clear that the solution is not to remove them entirely. This is simply not manageable and will only harm the system that it is trying to fix. It would instead be better to simply regulate them, in a way that people can still provide effective donations to support their chosen party or candidate, whilst avoiding any one individual or corporation from gaining any influence or causing any corruption within a government. We have seen increasing arguments arise calling for the regulation and / or removal of substantial donations and it is perhaps time to acknowledge these arguments, in order to improve the political and democratic system in which we all partake.

[B]y giving significant donations, donors may be given exclusive access to MPs and members of the cabinet.

9

Murder and the media

This article was published in the ATP Today magazine

Daisy Holroyd

Upper Sixth

The media is essential to the spread of information these days, whether it be via newspaper, radio or tv, media has an astronomical impact on what people know and their perception of what they know. To maintain this power the tabloids and news shows must have high audience interest rates, often resulting in news outlets primarily publishing stories with big shock value, such as war, politics and crime. A 1996 US news and world report article stated that the number of crime stories on the network evening news in 1995 was quadruple the 1991 total, despite the actual crime rates being lower; 375 of those stories were on murder, excluding the ones from the trial of OJ Simpson. A national survey in 1997 reported that of 1,500 respondents, 95% said they wanted to know about crime, a higher score than any other topic. But why is this?

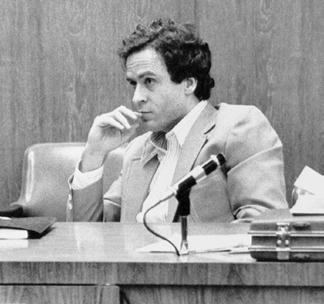

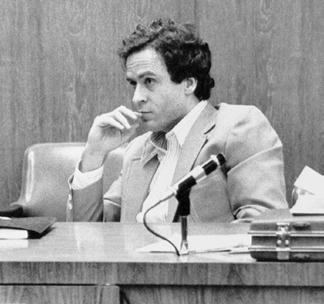

One theory is that women are attracted to such deviant men because they are jealous of the attention and spotlight they receive. When we make serial killers celebrities and household names in media and entertainment, they gain loyal fans; in the case of Ted Bundy in 1977 Hickey wrote, “several young women similar to his victims attended the court sessions and frequently corresponded with the killer; some wanted to marry Bundy, others believed they could help Ted”. Some believe that women see how much attention these criminals and their worshippers get and become obsessed, craving the 15 minutes of fame they may obtain from having a relationship with such a man as they are being incarcerated.

On the other hand, many believe that people are attracted to serial killers in order to try to understand why they commit such violent crimes. Human nature is to empathise with each other, so we often find ourselves trying to justify their heinous acts, especially if we know they’ve experienced traumatic events throughout their lives.

In fact, many serial killers have experienced some sort of trauma, in 2005 a child abuse and serial murder study was conducted by Mitchell and Aamodt. They selected 50 serial killers from the United States who had some sort of sexual gratification involved in their killings. Childhood abuse was categorized as abuse suffered by an

individual when they were under the age of 18, they divided childhood abuse into three subgroups; physical abuse, sexual abuse and psychological abuse and neglect. They concluded that childhood abuse is far more common across serial killers than the general population, except from neglect. Their results showed of the 50 serial killer participants, 36% suffered physical abuse, 26% sexual abuse, 50% psychological abuse, 18% neglect and just 32% reported no abuse at all.

Childhood trauma could be an explanation for some serial killers need for attention and media coverage is one way to gain attention fast, potentially making it a motive. On the other hand, some criminals are attracted to the feeling of power that accompanies high profile cases, this is particularly prevalent within male serial killers as a motivator. Regardless, we know that serial killers spend a hugely significant amount of time crafting their public images, whether it be by leaving letters and markings or by maintaining a pattern within the method of their crimes, watching the world glorify them fuels their desire to continue and even opens the doorway to other individuals who envy the spotlight.

So why is media such a dangerous catalyst to crime? Larry J Seigel’s Social Learning Theory proposes that “human behaviour is modelled through the observation of human social interactions, either directly observing those who are close and from intimate contact or indirectly through

media”. This suggests that by exposing the public, specifically those who are vulnerable to aggression, to so much crime, we may induce criminal behaviours in more individuals. Another theory Seigel introduced was Social Reacting Theory, the view that “people become criminals when significant members of society label them as such and they accept those labels as a personal identity”, so even if someone was falsely suspected of a crime but not convicted, they could be conditioned into believing they are a criminal and turn to something they may not have previously.

A study that suggests that media has a large-scale impact on the nature of crimes committed was a piece of research carried out by Rios and Ferguson about how media coverage of violent crimes affects homicide perpetrated by drug traffickers in Mexico based off the general aggression model. Exposure to media coverage of violent crime triggers the development of aggressive attitudes through desensitisation, someone previously not violent becomes violent - and the copycat theory - offenders mimic behaviour they see, showing that although crime rates in themselves stayed the same, criminals do tend to copy the worst of what they see in attempt to gather attention and notoriety to intimidate enemies.

To say that the media encourages crime is inaccurate, however it is clear that for many killers the speculation that surrounds being involved in a high profile case can be a main motivator; and for the general public, we have a tendency to get so engrossed in the intricacies of the crimes that we become desensitised and forget the victims and how they and their families have suffered enough without their trauma being aired to the world. Should news outlets, blogs and platforms for sharing be allowed to publish such sensitive information and articles? A straightforward answer is near impossible to reach, however a personal conclusion may be reached rather easily - do you believe that media has a significant impact on murder?

10

[P]eople are attracted to serial killers in order to try to understand why they commit such violent crimes.

Ted Bundy

Can animal therapy reduce the effects of dementia?

Dementia affects over 50,000,000 people worldwide and as of yet there is no cure for any Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD), the only treatments manage the symptoms. There are four types of dementia:

• Alzheimer’s disease

• Frontal Temporal dementia

• Vascular dementia

• Dementia with Lewy bodies

The most common symptoms are Behavioural and Psychological symptoms, BPSD – agitation, aggression, psychosis, anxiety and depression. Usually, they are given drugs like Donepezil to help manage symptoms, but the side effects, for example dizziness, can lead to hospital admissions. On top of that, caring for someone with an ADRD can be time consuming and stressful and caregivers have a high risk of depression as, especially in late stage ADRDs as the person can become totally dependent and full-time care is required, the demand of looking after someone who can become increasingly irritable and difficult can cause caregivers to neglect their own health and wellbeing,

ADRDs are caused when the cerebral cortex is damaged. In Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia, nerve cells die causing the brain to shrink, meaning that the whole brain and all its functions are eventually affected, but the cerebral cortex is the earliest part of the brain to be damaged. This is very problematic as this is where much of our higher order cognitive functions come from. It is made up of four lobes: the frontal lobe which manages thinking, the temporal lobe which manages auditory processing, the parietal lobe which receives sensory information and the occipital lobe which manages visual processing. The cerebral cortex makes us who we are and during dementia it is the first part of the brain to be affected, which is why many families can find it so hard to watch as the person they loved starts to slowly disappear; starting with forgetting memories, then losing control over their emotions, thinking deteriorates and eventually leads to that person passing away. Whilst there is

currently nothing that can cure ADRDs, reducing the effect of the symptoms can make a real difference to help a person suffering with dementia enjoy the time that they have left and reduce the emotional strain that loved ones of a dementia patient must go through.

Bryanna Streit, a researcher from Florida Atlantic University, has investigated the effect of an interactive toy pet on the BPSD and cognitive status of adults over 50 with Alzheimer’s or dementia. The goal of the study was to increase positive emotions, reduce risk of depression and improve cognitive status using a non-pharmacological approach which is safe, affordable, non-invasive and comes with no side effects. The use of toy pets rather than real pets eliminated potential concerns about the wellbeing of the animal and the owner.

Twelve people with mild-severe dementia from South Florida Adult Day Centre received a “Joy for all” companion pet cat which they used twice a week over twelve visits for one hour. The toy interactive pet (TIP) that was used in this study was a cat and only two participants initially expressed they would prefer dogs but later said they would make an exception after

naming and forming an attachment to their robotic cat. The TIPs provided a sense of comfort, entertainment, a companion and provoked conversation with other participants about memories of past pets. Results found that all mood scores improved over the 12 visits and 67% scored higher on their MMSE, mini mental state examination, which is used to measure cognition. Research suggests that potential benefits of implementing pet therapy could lead to a decrease in verbal aggression as well as the other symptoms which could make caring for ADRD patients a lot easier for caregivers.

The idea of animal therapy is a historically used idea: the ancient Greeks and physicians in the1600s are both thought to have used horses to lift the spirits of the severely ill, Florence Nightingale supported the use of animal therapy for psychiatric patients, she wrote in her book Notes on Nursing that “a small pet is often an excellent companion for the sick”, trips organised by the American red cross to look after farm animals were used for veterans suffering from trauma in the 1940s and small animals have been used to calm children down in hospitals. However, it was only formally researched in the 1960s when Dr Boris Levinson noticed that his dog had a positive effect on his young mentally impaired patients.

This article was published in the ATP Today magazine

11

[A] small pet is often an excellent companion for the sick.

Upper Sixth Izzy Jupe

Florence Nightingale

Josh Rowley (A Level)

Lucia Martin (A Level)

Josh Rowley (A Level)

Lucia Martin (A Level)

12

Katherine Withers (GCSE)

Bo Texier (A Level) Jess Watling (A Level)

(A Level) 13

Phoebe Hammond

Charlie Angel (A Level)

Natalia Schmitt (A Level)

Charlie Angel (A Level)

Natalia Schmitt (A Level)

14

Bella Gaunt (GCSE)

Chrissie Holligon (A Level)

Sophie Knowles (A Level)

Chrissie Holligon (A Level)

Sophie Knowles (A Level)

15

Abigail Svarovska (A Level)

An Analysis of the Representation of Conflict in Modern Art

Georgia Humberstone

Upper Sixth

Over the last century, we have seen as much war as ever, fought the most global and bloody battles in history, and built more mass graves than one could have ever imagined. Artists, however, have always been able to create from these atrocities, whether from their personal trauma or general frustration at the cyclical nature of human history. But why do artists seek to relive their trauma? Why do they look to shock their audience? Why do they fight what cannot be fought – human nature?

Of course, this all depends on the artist. Where Anselm Kiefer may aim to reclaim his culture from the clutches of Nazism, On Kawara may question the meanings of life and death. Where Mona Hatoum may despair in noting that wherever there is humanity there is conflict, Simon Norfolk may point out the repetitiveness of our past. Whatever personal or external inquiries they follow, there is one thing that brings them – and the rest of humankind –together: war.

Anselm Kiefer:

When considering the wars of modern history – and the atrocities that ensued –one cannot ignore World War II and, by default, Nazism and the Holocaust, both of which are explored extensively in the vast oeuvre of Anselm Kiefer. Taking inspiration from the work of Jewish poet Paul Celan, who himself was incarcerated in a forced labour camp during the war, Kiefer has created several pieces exploring the legacy of the holocaust, including the works ‘Sulamith’ and ‘Margarethe,’ named after the contrasting Jewish woman and ‘Aryan’ woman in Celan’s poem ‘Death Fugue.’

Kiefer’s use of materials portrays both the physical traits of the characters of Margarethe and Sulamith and the lives of the real people that they represent.

In ‘Margarethe,’ the straw used evokes the eponymous character’s “golden hair” and in ‘Sulamith’ the black painted straw imitates the Jewish woman’s “ashen hair.”

In ‘Margarethe’ the straw is partially blackened, still in the process of burning as its candle like flames slowly eat at the straw. Totally burnt in ‘Sulamith,’ the straw illustrates the destruction wrought on Jewish people in Nazi-occupied Europe, both figuratively as a symbol of wreckage

and literally as a reference to the thousands of Jewish people burned alive by the Nazis. In ‘Margarethe,’ the partial burning of the straw shows that while the persecution of Jewish people by the Nazis did not directly endanger “Aryan” Germans (so long as they complied), it portended an overwhelming loss of European culture and identity for which all Germans would be the poorer. Echoing the sentiment of another poem on the Holocaust, ‘First they came’ by Pastor Martin Niemöller (Niemöller, 2019), Kiefer shows through these paintings that, as the straw is still burning, the Nazi regime, had it not been defeated, would only have continued to seek out and destroy different ethnic, political and religious groups until all there was left to destroy was itself. This is Kiefer’s way of warning coming generations of the danger of the incitation of racial hatred – the promises of the instigators are never true, hatred never benefits the ones who hold it in their heart, it devours them from the inside out, causing only pain.

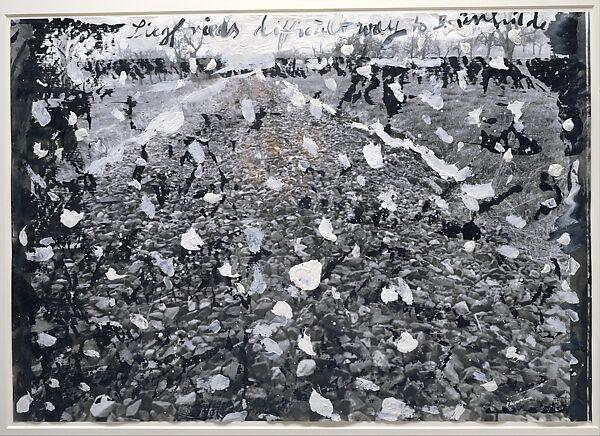

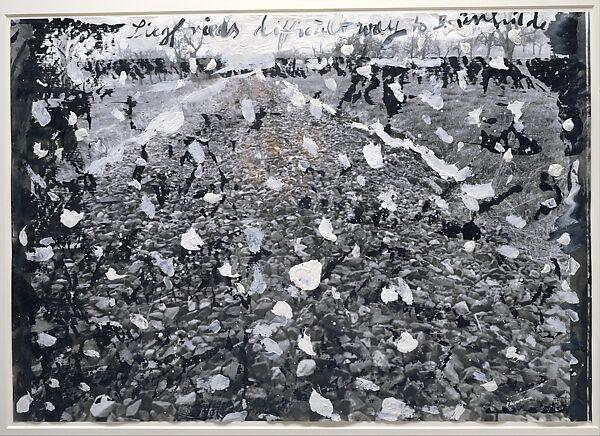

Another way in which Kiefer investigates his homeland’s past is through the reclamation of elements of German folklore that were corrupted by Goebbels’ propaganda machine. A work exemplary of this is ‘Siegfried’s Difficult Way to

Brünnhilde,’ the title of which refers to Wagner’s epic ‘The Ring Cycle’ and the hero Siegfried’s journey to his lover. Depicting a railway bed, the photo is painted with sporadic splotches of monochromatic acrylic and gouache, and at the top is written the title of the piece. The motif of a railway bed is used frequently throughout Kiefer’s art, suggesting Auschwitz and its infamous railway tracks. Such abhorrent connotations take the viewer instantly to one of the darkest times in recent human history, without directly referring to it. It is rendered even more sombre by the total lack of colour in the image. Contrasting the journey of condemned people towards concentration camps or death camps that they are not likely to survive, with that of the protagonist Siegfried in one of the most iconic German-language operas of all time demonstrates how great German history could have been but how harrowing it really was. In this way, it seems as if Kiefer is mourning his country’s potential for artistic greatness, as, after the Holocaust, Germany’s art will be overshadowed by national guilt.

Kiefer’s work is inextricably linked to the legacy of WWII and its associated

[T]he horror that he saw and heard stayed with him forever.

16

‘Margarethe,’ Anselm Kiefer

atrocities. He seeks to confront his country with its past through his art, so that one may never forget. After all, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” (Santayana, 1906).

On Kawara:

Like Kiefer, On Kawara knew what it is like to grow up in the rubble of a vanquished empire. Older than Kiefer, he witnessed the atrocities of war as a child. He was 13 years old when bombs dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima in his native Japan – and the horror that he saw and heard stayed with him forever.

His conceptual art was strikingly original, existential, and consistent, always working with time – or against it perhaps? A millennium, a year, a day; Kawara used the obvious tools for measuring life, but he used them in unconventional ways, he measured his life in days – not years – and he measured those days in people and places – not hours or minutes. Obsessed with time, Kawara incorporated the questioning of it into every aspect of his practice, revealing his misgivings about the purpose of life. Having grown up during a time when so many people died, it was inevitable that he questioned the reason he lived, and they did not. It could have easily been his city annihilated by an atomic bomb, but, for whatever reason, Tokyo survived with On Kawara in it. Luck, perhaps? Fate? Kawara’s investigation into humanity’s quantification of the universe is his way of questioning existence itself. Years and days are inventions of humanity,

not universal truths, and so, by questioning these things, Kawara shows how small and insignificant humanity is. We can try, but we will never understand why we are here.

Kawara’s best-known work is his monumental series of Today paintings, numbering just under three thousand by the time he died at 29,771 days old (Weiss et al., 2015). The idea of this series was to create a painting of the date every single day before midnight, white text on a variety of dark coloured backgrounds. Simple and meditative, this task was a life-long observation of the passage of time, noting each new day that he lived. The limited use of colour in the Today paintings keeps the focus on the date, rather than what happened on that day, showing that for Kawara all that mattered was that he was “still alive” (Kawara, 1973). Given his childhood in a country at war, perhaps the idea that all that is important is that he is alive comes from survivor’s guilt. No matter how difficult a singular day was for Kawara, at least he was alive, he could not say the same for others.

Also questioning human quantification of time is Kawara’s work One Million Years, a two-volume book project, of which the first book is titled ‘Past’ and dedicated to “all those who have lived and died” and the second book is titled ‘Future’ and is “for the last one”. Exhibited as an installation in which two people, a man and a woman, take turns to read a line starting with ‘Past’ and ending with ‘Future’, the books list every year from a million years in the past to a million years in the future (at the time of writing). As the books are read out, a normal human lifespan lasts just a few lines, demonstrating the fleetingness of life. In the grand scheme of the universe, we are all incomprehensibly tiny blips. This way of thinking about life was likely prompted by his childhood. Seeing all that death and suffering, he could not have helped but question the meaning of life and death itself.

Overall, On Kawara’s startlingly strippedback art style marks him as one of the most original conceptual artists of the 20th Century. His themes of life, existence and time were irrefutably influenced by growing up in Japan in the first half of the 20th Century, a time of political turmoil, war and death, which caused him to question the meaning of staying alive when so many people were dying.

Simon Norfolk:

While the world has not since seen war to the extent of WWII, where there is humanity, there is war. Responding

‘Sulamith,’ Anselm Kiefer

‘Siegfried’s Difficult Way to Brunnhilde,’ Anselm Kiefer

17

‘Today Painting,’ On Kawara

to modern conflicts, Simon Norfolk’s photography exposes the repetitive nature of human history and contrasts the natural world with humanity’s sins, creating a sense of despair at the inevitability of yet more war, yet more pain. A vocal critic of the United States, Britain and NATO’s military engagements in the Middle East, particularly in Afghanistan, Norfolk’s remarkable works expose these wars as neo-colonial lies. By all accounts against war, Simon Norfolk’s work also puts humanity’s conflicts in context with the world that we live in. Even if we move on, nature remembers.

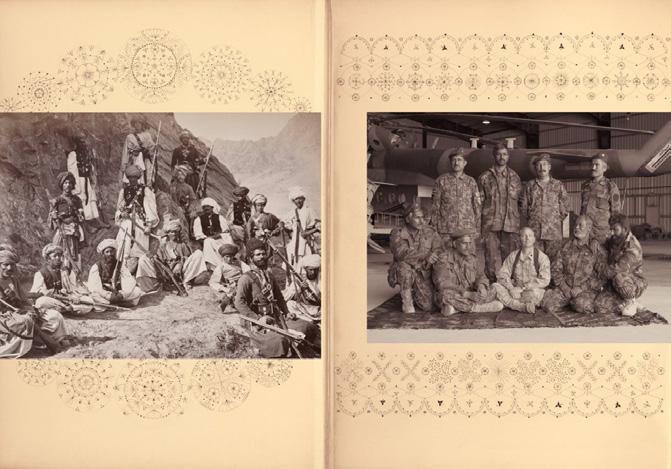

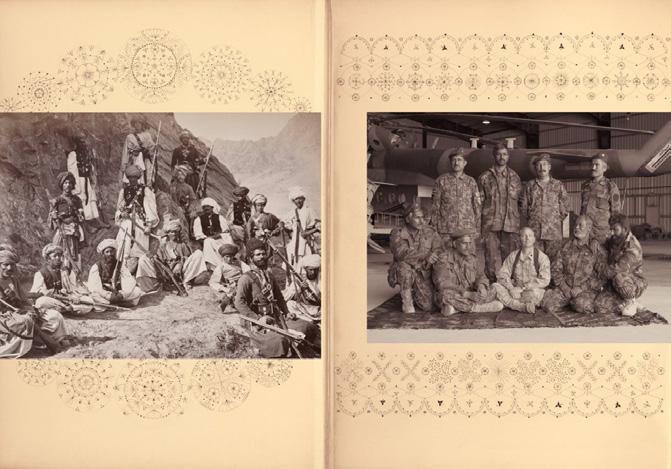

One of Norfolk’s most striking works is his “collaboration” with the Irish photographer John Burke (1843? -1900) who took the first ever photographs of Afghanistan, documenting the British empire’s first contact with the “mountainous and secretive” country (www.simonnorfolk. com, n.d.). While, being Irish, Burke was somewhat of an outsider from the imperial hierarchy, his photography served the British Empire by painting the war in Afghanistan in the light of white saviourism. Take, for example, the above pair of photographs: on the left is a photo taken by Burke of the Khan of Lalpura (a warlord), his followers, and his English

“handler” and on the right is Norfolk’s contemporary echo of this, members of the Afghan Airforce with their trainer, Maj. Jason A. Church of the US Marines. Both photos are examples of white people advising and training Afghans ‘in need’. Of course, things had changed: the nature of the conflict was different than before, but in noting the similarities between the two wars (the white foreigner training Afghans to fight in a war that they did not

start or even want), Norfolk shows that the mentality of westerners towards poorer, culturally different countries had not really changed, they were still seen, at least by the politicians who had any say in the matter, as countries that needed to be ‘civilised’.

Another of Norfolk’s stand-out photographs is that of an aluminium waste pond at a factory complex in Karakaj, on the border of Bosnia and Herzegovina and

‘Future leadership of the Afghan airforce’ Burke & Norfolk

‘Future leadership of the Afghan airforce’ Burke & Norfolk

18

‘Aluminium waste pond at the Karakaj aluminium factory complex,’ Simon Norfolk

Serbia. Published in the monograph ‘Bleed’ (Norfolk, 2005), the photograph seems to represent just that – blood. Contrasted with the snowy white canvas of the countryside is a red pool of manufacturing waste, sitting in the landscape like a deep wound. But this wound in the land is not just an illusion, this landscape is truly scarred by the atrocities and war crimes committed during the Bosnian War. One event in particular is the reason Norfolk photographed this scene: on the 14th of July 1995, hundreds of Bosniak Muslim men, some of whom were minors, were executed at the aluminium plant and thrown either into mass graves or into the lake. Of course, looking at this photograph, the viewer knows in their mind that it is not real blood, but the resemblance is haunting. Nature plays its part too, the white snow blanketing the land like the skin of a colourless, lifeless corpse. The leafless shrubs forming a natural barrier between the viewer and the stage of the mass execution, begging us to leave it alone, to let it heal. Humanity will not leave it alone though – there is still aluminium production taking place in the border town of Karakaj. Hence, all that this landscape has seen from humanity in recent years is destruction, whether of itself, with war and hatred, or of the landscape, through aluminium manufacturing, the process of which relies on fossil fuels (IEA, 2022)). With this comparison of how humans destroyed other humans, and how humans are destroying the world, Norfolk paints a cynical image of humanity, as a ruinous species that brings only carnage.

While the other artists’ work I have explored was affected and influenced by war, for Simon Norfolk war is not just an influence, it’s the main subject of his art. Norfolk sees humanity as the executioner, devouring not just others of our species but the entirety of the world, in a constant, selfdestructive pursuit of power.

Mona Hatoum:

A daughter of Palestinians exiled in Lebanon after the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, who later immigrated to London due to the Lebanese Civil War, artist Mona Hatoum knows what it is like to be displaced by conflict. Encompassing expatriation, separation and loss caused by war, Hatoum’s work transcends cultural barriers and tells a truly human story of conflict, unrest and the way it changes lives forever.

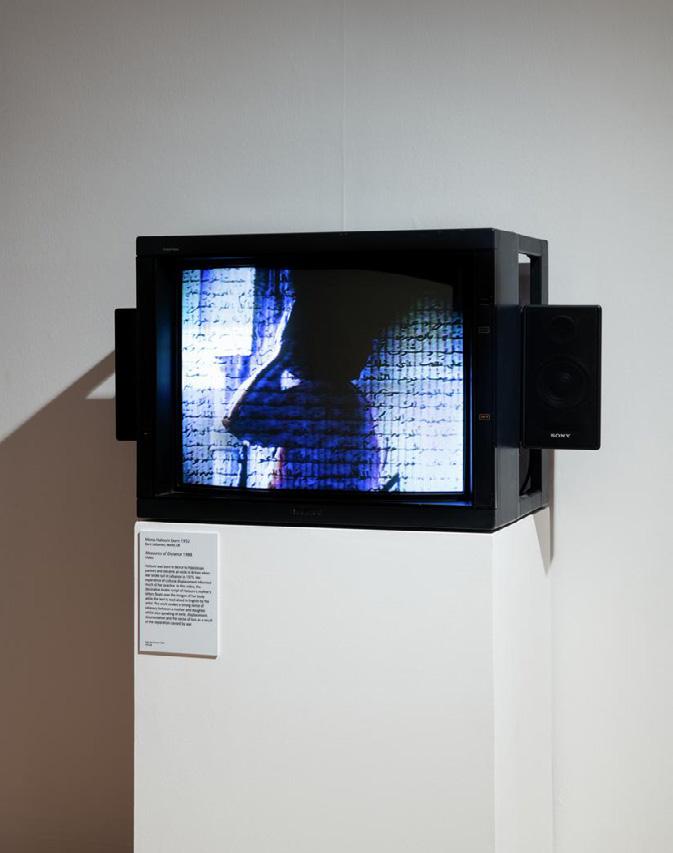

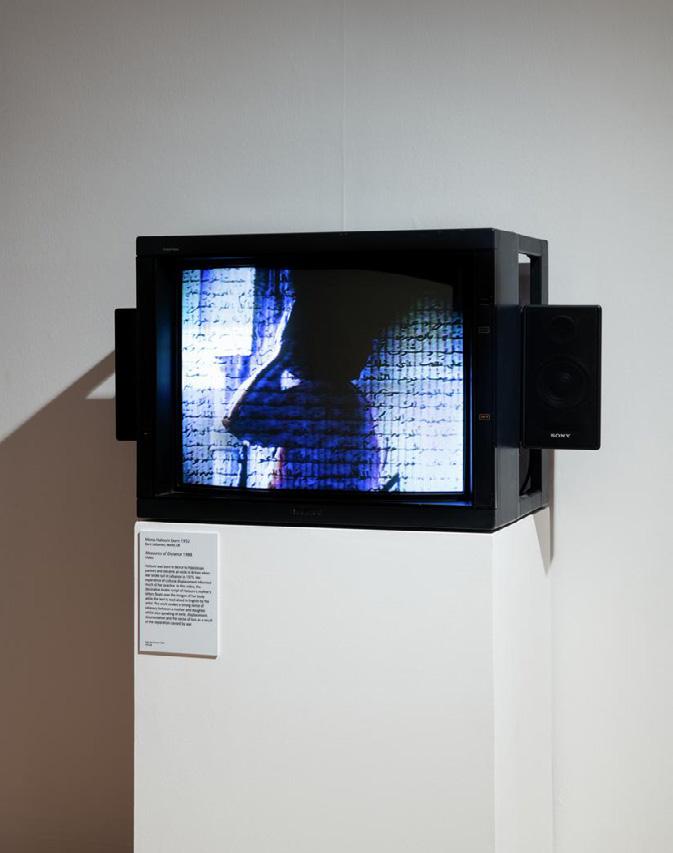

One of Mona Hatoum’s most intimate and personal works is her 1988 ‘Measures of distance,’ a film comprised of four layered elements: in the background play nude photos of her mother in the shower which

are somewhat concealed by Arabic text –correspondence between Hatoum and her mother – layered on top of it. The audio is a taped conversation in Arabic between mother and daughter in which they talk freely about their feelings, sexuality and about fragile masculinity. The conversation is intercut by Hatoum reading her mother’s letters in English. Being nude, the film becomes a deeply intimate portrait of Hatoum’s mother and their relationship as it lets us see the real person without any barriers. In Hatoum’s reading of the letters, her mother tells her that her father was angry about the photographs, as if he owned her body and felt that Mona had infringed his property. Yet, at the same time, she gave her daughter full permission to use the images in her art, as long as Mona did not tell her father. In this way, the film subverts the stereotype of an Arab mother as a non-sexual, passive person by presenting Hatoum’s mother as a woman

who has sexuality and is rebellious in her defiance of her husband’s wishes. That being said, the text layered over the images, partially concealing them, shows that she is not just sexual, she is intelligent and she has a personality; basically, it demonstrates to the audience that Hatoum’s mother is a full person with an identity and not just what misogyny and colonialism might teach us about an Arab mother.

Although the most obvious subject in the film is Hatoum’s relationship with her mother, it also reveals the effects of war on her. As we come to the end of the film, Hatoum’s mother writes to Hatoum telling her about how lonely she has become due to the war. She is isolated from her children, who cannot return to Lebanon because of the war and she can hardly even visit her family that lives in Lebanon due to the danger outside of her home. Illustrating how war and displacement cuts people

19

‘Hot Spot III,’ Mona Hatoum

off from their support systems, rendering them even more vulnerable to the traumatic mental effects of conflict, Hatoum is denouncing the war for the pain it has caused her family.

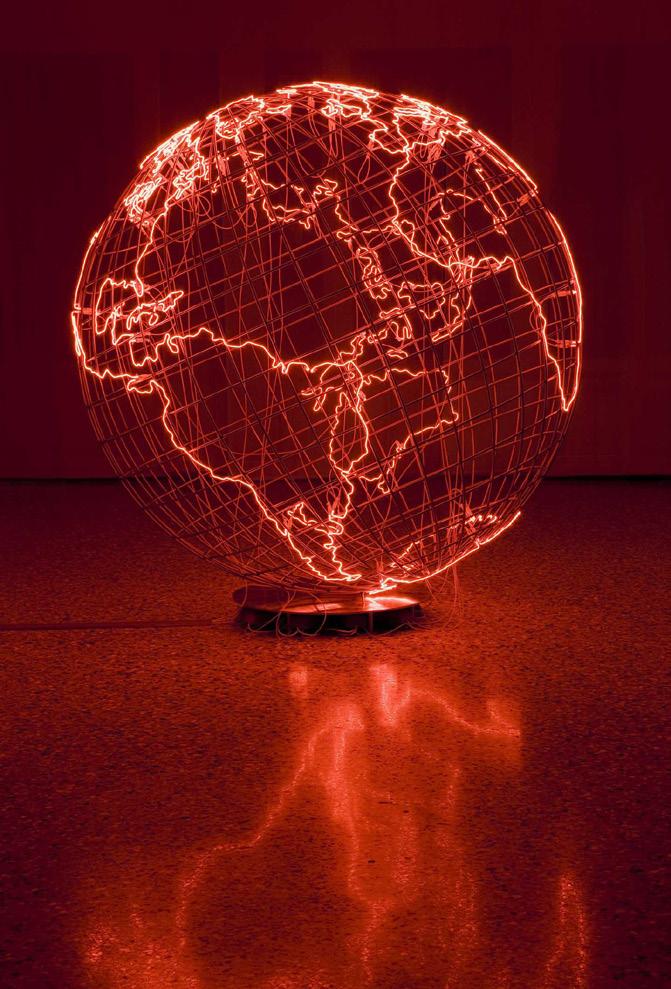

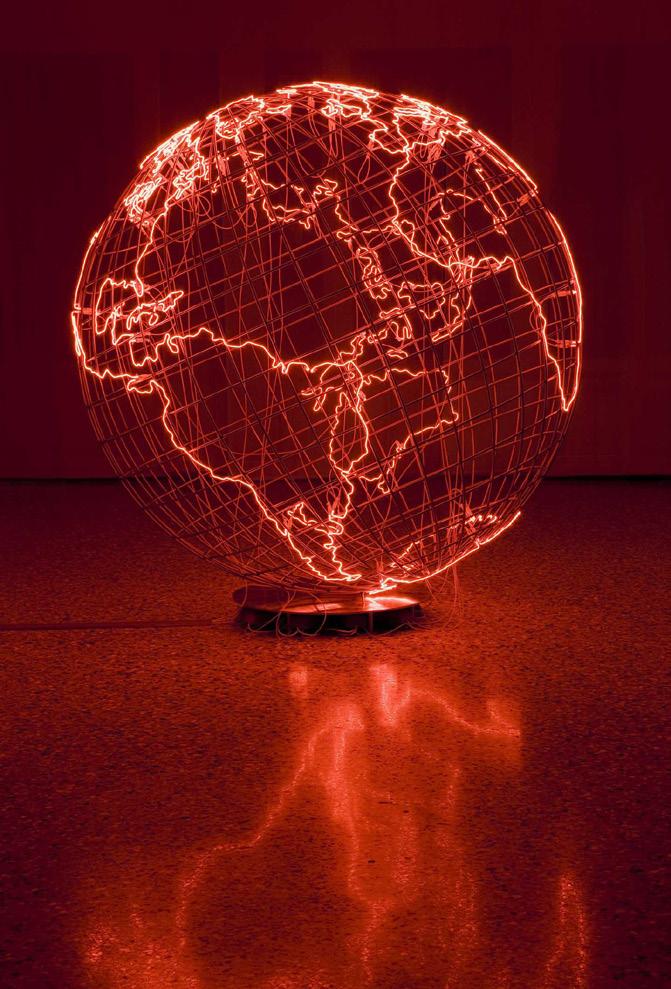

Another artwork by Hatoum that deals with war, ‘Hot Spot III,’ a globe made of metal adorned with continents of neon lights, demonstrates Mona Hatoum’s despair at humanity’s unrelenting pursuit of war. The title of ‘Hot Spot’ refers to a term meaning a place of military or civil unrest. By delineating the continents in red neon lights, red being a symbol of danger, Hatoum suggests that the whole world is a ‘hotspot’. If the whole world is a ‘hotspot’, then war is an inevitability of human nature, and wherever we go, war and its atrocious consequences follow. The curved metal bars that make up the globe suggest a cage, as if the world is trapped within this

endless cycle of war. The idea that all of humanity, no matter where we are on the planet, is trapped in a repetitive pattern of war illustrates Hatoum’s disappointment with humanity, as it has consistently failed not just her and her people, but also everybody else that has been touched by the devastating hand of war.

Although war is not the main theme in all of Mona Hatoum’s work, its sinister influence can be found throughout all that she has done. For example, ‘Measures of Distance’ shows that although life goes on where it can, once you are affected by war, its presence is always there.

‘Hot Spot III’ however is a work directly confronting war and its consequences. Overall, in exploring war, separation and culture, Hatoum’s art demonstrates the persistence of war and shows despair at the apparent inevitability of it and its consequences.

Conclusion:

From WWII to the Lebanese Civil War, the representation of conflict in modern art screams out at the viewer, begging us to not repeat the pain of the past. Obsessive with his warnings for his country, Anselm Kiefer’s work is an obvious example of this plea. In confronting Germany with its atrocious, deadly past, for example in his works based on the poems of Paul Celan, Kiefer aims to protect the world from the repetition of such destruction. However, artists Mona Hatoum and Simon Norfolk know that this is a fruitless effort. In Hatoum’s eyes, war is an inevitability of humankind, evidenced by her work ‘Hot Spot III.’ At the same time, Norfolk’s work with the photography of John Burke clearly illustrates the repetitive nature of human history. Despite their belief that war will always persist, both Hatoum and Norfolk continue to expose the devastating consequences of war in an attempt to prevent it, fighting an impossible battle against human nature.

Whether war can or cannot be prevented is not the focus for On Kawara, in fact war is hardly even mentioned in his work. However, war’s silent presence within Kawara’s work is undeniable as the artist was forever changed by the war he witnessed in his youth. Kawara’s existentialism is a direct consequence of war and for this reason his work on time and existence shows the impact of conflict on modern art. Also showcasing the consequences of war is the oeuvre of Mona Hatoum, an artist forever displaced, whether that be from growing up as a Palestinian exile in Lebanon or from being forced to leave Lebanon for England due to the civil war. Both of these displacements become obvious in her work ‘Measures of Distance.’ Consciously or unconsciously, both of these artists present conflict in their art through its terrible consequences.

Having explored these artists, it has become clear that once exposed to war, artists cannot resist it’s influence in their work; Norfolk was compelled to examine motives behind war once he understood the reality of war in the Middle East, Hatoum has the pain of war in her genes, Kawara witnessed the desolation of his country, and Kiefer grew up in the rubble of his. From red hot globes to railway tracks, these transformative experiences are reflected in the oeuvre of each artist, thus leading to the simple realisation: war is a tenet of human nature, so is art. Hence, as sure as the sun will rise, there will be more war, more pain, and more art.

‘Measures of distance,’ Mona Hatoum

20

[B]oth Hatoum and Norfolk continue to expose the devastating consequences of war in an attempt to prevent it.

The Red String

Beth Roberts

Everyone seems to be looking for ‘the one’, a soulmate, someone to love forever, something that makes sense in a nonsensical and ever-changing world. Whether you’re a cynic or a romantic, everyone can appreciate a good myth.

Homer first speaks of fate (moira) as a singular power, but the poet Hesiod goes on to establish the Fates as three old women who spin threads to determine human destiny, often attributed to a particular time period, named Clotho (the spinner, present), Lachesis (allotter, the future) and Atropos (inflexible, the past). The Romans had similar ideas with Nona, Decuma and Morta. The Fates were portrayed originally as fatherless daughters of Nyx, but later as the offspring of Zeus and Themis. Orphic cosmology presents their mother as Anake. The women were frequently portrayed as old and ugly in literature, but in art they were often very beautiful. It is said that when a

baby is born Clotho spins their life thread, Lachesis measures how long they will live for and finally Athropos cuts the thread with her shears when their life comes to an end. Together they represent inescapable human destiny and everyone’s threads make up a complex web-like tapestry.

The red string of fate is different to your main life thread and is featured in many different cultures. In Chinese mythology it is tied around the couple’s ankles, in Japanese culture it is bound from a male’s thumb and from a female’s little finger to their partners; in Korean culture the red thread is from each of their little fingers. In Chinese lore the deity in charge of the red thread is Yuè Xià Laorén, the ‘old man under the moon’, who seeks out couples to bind together in an unbreakable bond. In one story, a boy walks home on a dark night and meets an old man (Yuè Xià Laorén) standing under the moonlight. The

man shows the boy he is attached to his future wife by a red string, but the young boy, wanting nothing to do with romance, throws a stone at her. Many years later the boy has grown up into a young man and his parents arrange for him to be married. When he meets his bride and lifts up the traditional veil covering her face, he notices she is wearing a strange piece of jewellery above her right eyebrow and when he removes it he sees the scar beneath where she says a boy threw a stone at her when she was young. This story embodies the belief that the red thread of fate connects two people destined to be together regardless of time, place or circumstance and although it may stretch or tangle it never breaks. Chinese culture celebrates the symbolism of the colour red by featuring it in weddings where the bride and groom wear it throughout or at some point during the rituals. The red thread is very similar to the Western concept of soulmates.

21 Plato

Lower Sixth

In ‘The Symposium’, Plato discussed soulmates and explained that God created joined humans with four legs, arms and two faces. These beings were prideful and wanted to overthrow the Gods, so Zeus separated them as a punishment by splitting them in half and putting their genitals on their backs. These newly separated humans wandered the Earth looking for their other half in devastation. Over time, the humans became miserable from loneliness and with the inability to find their other half they starved to death. Apollo took pity on the humans and stitched them where they were cut apart, moving their genitals back to their front so that heterosexuals could produce offspring as offerings to the Gods and both they and homosexuals could find love and happiness. Some continued the search and found their soulmate, but most found contentment with another.

The issue of soulmates continues to affect society today, with people holding out for someone who might not even exist. There are many cases of relationships ending prematurely over very fixable problems or disagreements, simply because people have an unrealistic expectation of love. From a young age we are exposed to movies, books and articles that tell us what to expect from your partner and show us these perfect couples who never fight, and every story ends with a happily-ever-after straight from Disney. Humans are curious beings by nature and inherently selfish due to innate survival instincts. This makes for people who are too paralysed by fear to enter into a relationship that could possibly end, or people who are so focused on this idea of ‘the one’ that they sabotage good relationships, because they don’t match up to this perfect ideal in their mind.

The argument of “tis better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all”, famously said by Tennyson, is one that plagues people even now. It would suggest in relation to soulmates that you shouldn’t spend your life searching for the person at the end of your red string and should rather not fear falling in love and attaching yourself to another person even if it’s not the person you spend the rest of your life with, because love is the strongest emotion of them all and one that everyone deserves to feel, so whether you lose or hold onto your love, it is better to feel something real than to hide from heartbreak.

The term ‘forever’ is continually misused in regard to love. People make these larger-than-life declarations with enough hyperboles to make astrological references

seem tolerable and forget that you cannot promise someone ‘forever’. Life is highly unpredictable; one of the reasons why many take comfort in ideas like fate is so that something is guiding them throughout their lives. Due to the unforeseeability of existence no-one can promise to be with someone for an immeasurable amount of time. Not only is it not physically possible given the human lifespan, but it is disingenuous to swear a never-ending future with someone when you are fully aware that will never happen. I suppose fate is a far more becoming alternative to life without such beliefs, giving your life some sort of meaning and worth whether you accomplish anything or not. There is a sort of blame sharing to it and a relinquishing of harsh memories in favour of a planned pathway that means all you suffered for will be worth it as everything will miraculously work itself out in the end so you will find happiness. I think this very optimistic view of life is somewhat naive, but very comforting, so I can understand why many people believe in it. To believe in an existence without purpose, meaning or any insight to your future is a very daunting

task, but when you choose not to believe anything or anyone has a plan laid out for you, you can seize control of your own destiny and give your life any purpose you choose. It is a very freeing experience when you choose to make things happen and not let fate decide things for you: carpe diem.

Therefore, in love and life, choose to create your own happiness, embrace new opportunities and don’t fear the unknown or possibility of ending up alone. Every decision you make and don’t make contributes to a million possible alternative realities and not making a choice is still a choice. Whether you meet the person at the other end of the red string or don’t, remember that if you open up your soul to another person, you might just find your soulmate, not as Greek mythology states it, but rather, someone who understands you like no other, who treats you with love and respect and as an intellectual equal, who you may not always like, but you will always love. In a world full of uncertainty and misfortune, we need to reclaim and reinvent the word ‘soulmate’ to be someone who isn’t perfect, but is right for you.

22

Clotho spinning life thread

As a cosmological concept, the idea of our universe as merely one parallel member of a much larger ‘multiverse’ dates back to the fifth century B.C., and a philosophy known as ‘atomism’. These Ancient Greek natural philosophers supposed that the universe was made up of tiny, indivisible particles called atoms, which determine not only the objects around us, but also our perceptions and emotions - it was thought that tastes were caused by the texture of atoms, and temperature caused by the atoms’ friction. It was suggested that our universe was the result of these atoms colliding randomly with each other in a vacuum that Democritus called “the void”, and that these collisions formed many other, less perfect, parallel universes. However rudimentary this explanation of the cosmos may seem now, it introduces the multiverse as one of humanity’s first attempts to explain the origin of our universe without the help of a divine creator. The current revival of this ancient idea has come as a response to some of the most perplexing mysteries about our universe facing modern-day physicists, due to its extraordinary explanatory power.

Although the multiverse seems to be a convenient answer to a lot of the questions we currently have, it is important to remember that the multiverse hypothesis is still only a hypothesis, and will remain so until we have conclusive evidence on which we can accept it as a scientific theory.

The enormity of a potential proof of the multiverse hypothesis cannot be overstated: string theorist Brian Greene describes such a proof as “the biggest upheaval of our understanding of cosmology since Copernicus proved that Earth wasn’t at the centre of the universe”.

How Likely Is the Multiverse?

Within the scientific community, many different hypotheses about the multiverse have emerged - physicist Max Tegmark attempted to categorise the various multiverse hypotheses into four ‘levels’ of multiverse as early as 2003, and the

James Restell

aforementioned Brian Greene went further in proposing nine levels of multiverse in 2011.

The numerous suggested multiverses illustrate the problem facing the multiverse hypothesis - its foundations in scientific conjecture. Some claim that belief in the multiverse is akin to religious belief in its complete lack of evidence. However, this argument doesn’t appreciate the perfectly rational scientific reasoning behind the modern revival of the hypothesis. If we take evidence as “that which justifies belief”, the fact that the multiverse explains many of the major astrophysical questions that are currently unanswered could arguably fit this definition, providing substance to the multiverse’s claim. In recent years, science has produced significant amounts of “suggestive evidence”, meaning “results that indicate a strong possibility of something without decisively proving it”, making belief in the multiverse hypothesis a potentially rational belief.

The Argument from Fine-Tuning Our universe appears to be perfectly suited to our needs, almost custom made for