BACKDIRT

ANNUAL REVIEW OF THE COTSEN INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY AT UCLA

FRONT COVER: Graduate students Brandon Keith (UCLA) and Mia Evans (University of Kent) use geophysical methods to investigate the remains of the Church of San Giovanni di Dustria, near Turin, Italy, in September 2022.

BACK COVER: Anya Dani, director of community engagement and inclusive practice as well as a lecturer at the UCLA/Getty Interdepartmental Program in the Conservation of Cultural Heritage, works on ancient pottery. (Photograph by Peter Ginter, Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology.)

ABOVE: After years of online meetings, Moupi Mukhopadhyay, a graduate student in the conservation of cultural heritage, presents “Understanding Pigment Composition in Kerala Temple Murals Using Non-Invasive Imaging Techniques,” the first of our hybrid (both in-person and online) Wednesday Talks (formerly Pizza Talks), on October 12, 2022.

To request a copy or for information on submissions, please contact the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press via email at: nomads@ucla.edu

Read Backdirt online at: http://ioa.ss.ucla.edu/content/backdirt ©2022 UC Regents

Willeke Wendrich Director of the Cotsen Institute Randi Danforth Publications Director, CIoA Press Hans Barnard Editor, Backdirt Roz Salzman Assistant Editor, Backdirt Peg Goldstein Copyediting Sally Boylan Designcontents

back D irt 2022

Message fro M the Director

4 Willeke Wendrich

t he i nstitute in the n ews

5 Robbert Dijkgraaf, Minister of Education of the Netherlands, Visits UCLA and the Cotsen Institute

6 Giorgio and Marilyn Buccellati Receive Prestigious Balzan Prize

8 NEH Awards Conservation Program $310,000 for Training in Preservation of Indigenous Collections

8 Glenn Wharton Honored with Conservation Award

9 Sarah Beckmann Awarded Rome Prize Fellowship

10 Justin Dunnavant Welcomed as Scholar in Residence at Occidental College

11 Justin Dunnavant Attends Artifact Analysis Workshop in Monticello, Virginia

11 Two Cotsen Institute Alumnae Accept Tenure-Track Positions

13 Vanessa Muros Awarded Boochever Endowment

14 Cotsen Affiliates Present at Congress in Turin, Italy

15 Gregson Schachner, Reuven Sinensky, and Katelyn Bishop Contribute to Book Honored by the SAA

15 Christopher Donnan Publishes Book on a Royal Moche Tomb

f ro M the f iel D

16 Transformation of a Sacred Landscape around Lake Gilli, Armenia

Arsen Bobokhyan and Kristine Martirosyan-Olshansky

28 Bikol, the Philippines

Robin Meyer-Lorey and Stephen Acabado

32 St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands

Justin Dunnavant

34 Underwater Archaeology Near Maui and Lana’i

Justin Dunnavant

36 Industria (Monteu da Po), Italy

Hans Barnard and Willeke Wendrich

42 Fire on Rapa Nui (Easter Island)

Jo Anne Van Tilburg

50 The Forgotten War in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia

Hans Barnard and Willeke Wendrich

M ESSAGE from the Director

I HAVE AT TImES wondered why our annual report is called Backdirt. For non-archaeologists, this term has little meaning, so in brief: backdirt is the sand, soil, or rocky matrix left behind after the digging is done, the soil has been sifted, and the samples and finds have been cataloged, studied, and stored. In most cases, backdirt then becomes backfill: it is put back in the hole, covering and protecting whatever ancient remains are left underfoot. For archaeologists, it has positive connotations. Dirt is a term of pride. A dirt archaeologist is the opposite of an armchair archaeologist. He or she is someone who is not afraid of physical labor, getting dusty and sweaty; someone who thinks through the point of a trowel or the hairs of a brush.

Yet archaeology is rapidly changing. Much of our work is now nondestructive: geophysical methods can map out what lies underground without actual digging. A slew of techniques for the analysis of excavated material allows greater insights from less material. Our emphasis has shifted from discovering objects and buildings to finding things out. Many archaeological finds and archives that were never published are worthy of finally being published, even if the original excavator has long since retired or passed away. So increasingly, dirt archaeologists are getting less dirty (although storerooms and archives can be pretty dusty) but are no less involved in the materiality of our discipline.

The back in Backdirt probably makes sense if we consider an annual report to be about looking back, but that’s the thing: we are equally looking forward. In this volume you will find out how local conflicts directly affect archaeological projects in Tigray (Ethiopia) and Rapa Nui (Easter Island). On the brighter side, you will also read preliminary reports of recent fieldwork, much of which has been on hold for at least two years.

We are welcoming new cohorts of students in archaeology and conservation, and gradually the basement of the Fowler Building is becoming filled with voices again. I want to thank Greg Schachner, who served as chair of the Archaeology Program under very difficult circumstances, and to welcome Stephen Acabado as the new program chair. We also welcome new postdoctoral scholars, lecturers, and faculty members. Piphal Heng is a two-year postdoctoral scholar at the Cotsen Institute and the Program for Early Modern Southeast Asia. Greg Woolf, the Ronald J. Mellor Distinguished Professor of Ancient History, has joined the core faculty of the Cotsen Institute. Anya Dani is the inaugural director of community engagement and inclusive practice, as well as a lecturer in cultural heritage conservation for the UCLA/Getty Interdepartmental Program in the Conservation of Cultural Heritage. The program is also strengthened by the arrival

of Thiago Sevilhano Puglieri, a professor in the Art History Department with a background in chemistry. Our website has more information in the news section.

With that, I come to the large amount of work dedicated to providing up-to-date information on our website (https:// ioa.ucla.edu) concerning news, special events, and the accomplishments of staff, students, and faculty. Many times, I hear, “I was not aware of that,” while the fact in question featured on our website recently. Emails that draw attention to new entries are circulated regularly but are probably deleted rather than read. That’s understandable considering the avalanche that fills our inboxes, but please take a moment and check our website and its archive now and again to remain up to date. For its content, and that of Backdirt, we are obviously dependent on your contributions, so please do not hesitate to forward anything noteworthy to Roz Salzman (rsalzman@ioa.ucla.edu) or Hans Barnard (nomads@ucla.edu).

The Covid-19 pandemic stopped almost all fieldwork in its tracks but also resulted in two very well-filled issues of Backdirt. These included important reflections on the world in general and on the disciplines of conservation and archaeology in particular. It seems that our forced pause was helpful in some aspects, but it was devastating for students in the midst of their research. Despite or because the summer of 2022 saw a return into the field for many of us, this issue of Backdirt is slightly slimmer than those from the previous two years. I do hope that it provides you with both information and inspiration.

Willeke Wendrich Director, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Cotsen Institute Director Willeke Wendrich

Cotsen Institute Director Willeke Wendrich

THE INSTITUTEIN THE

Robbert Dijkgraaf, Minister of Education of the Netherlands, Visits UCLA and the Cotsen Institute

As part of an ongoing effort to strengthen collaborations between UCLA and Dutch universities, Jo Anne and Johannes Van Tilburg hosted Robbert Dijkgraaf, the Dutch minister of education, culture, and science, during his visit to UCLA on September 9, 2022. Before accepting the position of minister, Dijkgraaf, a theoretical physicist working on string theory, was director of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey.

The event, the culmination of a two-week trip to visit universities, major corporations, and governmental agencies in the United States, was cosponsored by the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology and the Center for European and Russian Studies (CERS) at the UCLA International Institute. UCLA Dutch Studies, under the direction of CERS, is the largest program in the United States focused on the study of the Netherlands and Belgium in a global perspective, promoting student and faculty exchanges and scholarship in Dutch language and culture. The Cotsen Institute is a premier research organization dedicated to the creation, dissemination, and conservation of archaeological knowledge and heritage. It also houses the UCLA/Getty Program in the Conservation of Cultural Heritage, which educates and trains students in the highest standards of the conservation of material culture.

The minister and his delegation were welcomed by Darnell Hunt, UCLA executive vice chancellor; Anna Spain Bradley, vice chancellor of equity, diversity, and inclusion; and other campus leaders and faculty, including Laurie Kain Hart, director of CERS. “In keeping with UCLA’s mission of global reach, it was a great honor to welcome Minister Dijkgraaf and his delegation to UCLA for a rich exchange of knowledge across cultures and nations,” Spain Bradley said. “The minister’s deep commitment to the power of education to advance inclusive societies in which all peoples can thrive is a vision that UCLA and I share. We look forward to continued cooperation with the minister and the government of the Netherlands in years to come.”

Alex Swart, board member of the Netherland-America Foundation, Southern California Chapter, attended the luncheon with several NAF colleagues and explained, “Our organization supports meaningful exchanges between the Netherlands and Southern California in the science, commerce, culture, and education spaces, which of course include Dutch Studies and the annual Van Tilburg Lecture at UCLA, a highlight in the intellectual life of the Dutch community in Los Angeles.” The annual Johannes Van Tilburg Lecture in Dutch Studies was established in 2005 by a generous gift from Johannes and Jo Anne Van Tilburg for the establishment in perpetuity of an annual lecture in Dutch studies, as part of an exchange program between UCLA and the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands.

Johannes Van Tilburg has served for more than a decade as honorary consul of the Netherlands for Los Angeles.

Jo Anne Van Tilburg is director of the Rock Art Archive at UCLA and an associate researcher at the Cotsen Institute, as well as principal investigator of the Easter Island Statue Project. She noted, “The Van Tilburg family is proud and very pleased to support the Johannes Van Tilburg Lecture in Dutch Studies within the UCLA International Institute. The important watchword inclusion, which is inherent in the approach of UCLA to higher education and a shared goal with the Dutch Ministry of Education, tends to suggest the generosity of sharing something already established. Perhaps at UCLA it could be amended to expansion, which better describes growth in cooperation with the community as a whole and within the long-established UCLA tradition of diversity.”

Willeke Wendrich, director of the Cotsen Institute, welcomed the visitors via Zoom from Budapest (Hungary), where she was attending a conference. Herself an alumnus of Leiden University in the Netherlands, Wendrich noted, “The push by UCLA for equity and diversity is extremely important, and I am delighted that we have been able to hire a diverse faculty. It is also important to put in the minds of all young students that UCLA is something they can aim for. The combination of having a role model and being told ‘this is for you’ is very powerful.”

At the conclusion of the meeting, Dijkgraaf reported, “This isn’t just the end of the trip; this is a grand finale. UCLA made sure we finished our visit to the United States on a very high note.” ■

Giorgio and Marilyn Buccellati Receive Prestigious Balzan Prize

On February 2, 2022, the International Balzan Prize Foundation announced that Giorgio Buccellati and Marilyn Kelly-Buccellati had been awarded the 2021 Balzan Prize for Art and Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. This prestigious prize is awarded annually to a maximum of four recipients and includes a cash component for each recipient of approximately $800,000, half of which must be invested in research by young researchers. Previous winners have included several Nobel Prize laureates. The aim of the prize “is to foster culture, the sciences, and the most meritorious initiatives in the cause of humanity, peace and fraternity among peoples throughout the world.”

Giorgio Buccellati is a professor emeritus of the Department of History and the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures and the founding director of the Institute of Archaeology at UCLA, now the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology. He is also director of the Mesopotamian Laboratory. Marilyn KellyBuccellati is a professor emerita of archaeology and art history at California State University–Los Angeles. Both are researchers affiliated with the Cotsen Institute.

Giorgio and Marilyn received the award “for their achievements in the study of Hurrian culture and for highlighting its importance as the foundation of a great urban civilization, among the most flourishing in the ancient Near East in the third millennium BCE; for promoting a digital approach to the study of archaeology; and for enhancing theoretical reflection on the nature of this discipline,” according to the announcement by the Balzan Prize Foundation.

The International Balzan Foundation was created in Lugano, Switzerland, in 1956 by Lina Balzan, daughter of Eugenio Francesco Balzan. Upon his death she decided to use his wealth to honor his memory. Eugenio Balzan was born on April 20, 1874, in Badia Polesine, near Rovigo in northern Italy, into a family of landowners. He spent almost his entire working life at Corriere della Sera, the leading newspaper in Milan. After joining the paper in 1897, he worked his way up from editorial assistant to news editor and special correspondent. In 1903 editor Luigi Albertini made him managing director of the paper’s publishing house, of which he became a partner and a shareholder. In 1933 he left Italy for Switzerland,

where he had successfully invested his fortune. He continued his significant charitable activities until his death in Lugano in 1953.

Nominating letters on behalf of the Buccellatis came from an array of distinguished international scholars who have worked with them over the years. The letters praised their efforts in the areas of archaeological theory, art history, conservation, digital analysis, fieldwork, institutional commitment, and public archaeology. The letters were signed by Max Hollein, director, and Daniel Weiss, president and CEO, of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; Tim Whalen, director of the Getty Conservation Institute in Los Angeles; Sarah Kansa, executive director, and Eric Kansa, program director, of Open Context in Berkeley; Wang Wei, president of the Institute of Archaeology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences; Nazeer Awad, director general of the Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums in Damascus (Syria); Christian Greco, director of Museo Egizio in Turin (Italy); Stefano Valentini, director of the Center for Ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern Studies in Florence (Italy); and Willeke Wendrich, director of the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology.

In his letter from the Getty Conservation Institute, Whalen writes that the work of the Buccellatis “reflects an extraordinary blend of scholarly erudition and pragmatic

commonsense. They see near and far. Practicing archaeologists who have embraced both site and artifact conservation, innovators and experimentalists, brilliant networkers across multiple disciplines with the ability to engage help effortlessly from others with different expertise—these are the attributes of Giorgio and Marilyn. Their contribution to the integration of preservation, archaeology, and community comprises a milestone. Their record of accomplishment is stellar. We stand in admiration of their inventive ways of harnessing the benefits of archaeology for a larger purpose and in ways they never would have imagined— as a bulwark against the ravages of war.”

Wendrich congratulated the Buccellatis, whom she has known as colleagues for more than 20 years, on their well-deserved award, which she enthusiastically supported. In her letter of nomination, she extolled both professors as “great educators. They have trained students from UCLA, several Italian universities, the University of Damascus, and schoolchildren from the nearby city of Qamishli. They are fundamentally concerned with the safety and well-being of their Syrian counterparts and support a large community by helping to develop economic opportunities. Central to their work are the deep historical roots of the region; at the forefront of their minds are the living communities.” ■

THE INSTITUTE IN THE NEWS

NEH Awards Conservation Program $310,000 for Training in Preservation of Indigenous Collections

The National Endowment for the Humanities has awarded the UCLA/Getty Program in the Conservation of Cultural Heritage a grant of $310,362 for a project titled Preservation of Indigenous Collections: Training for Tribal Materials and Museums, to be directed by Ellen Pearlstein, a professor in the Department of Information Studies and the UCLA/Getty Program in the Conservation of Cultural Heritage and a core faculty member of the Cotsen Institute.

The award will fund a continuing education program for collections stewards that will include six online courses, two in-person regional workshops, and followup mentoring to support sustained application of lessons learned. The program is targeted to Native Americans working with tribal materials at museums and cultural centers across the country. Critical to preparation of the winning proposal were two staff members of the Mellon Opportunity for Diversity in Conservation program: Bianca Garcia, program manager, and Nicole Passerotti, program associate. Pearlstein is project director for the Mellon program.

Glenn Wharton Honored with Conservation Award

NEH Preservation and Access Education and Training awards are made to organizations that offer national, regional, or statewide education and training programs across the pedagogical landscape and at all stages of development, from early curriculum development to advanced implementation. Awards help the staff of cultural institutions, large and small, obtain the knowledge and skills needed to serve as effective stewards of humanities collections. They support projects that prepare the next generation of preservation professionals as well as projects that introduce heritage practitioners to new information and advances in preservation and access practices. ■

Glenn Wharton, professor of art history and chair of the UCLA/Getty Program in the Conservation of Cultural Heritage, which is part of the Cotsen Institute, has received the 2022 Sheldon and Caroline Keck Award for outstanding and distinguished contributions to the field of conservation from the American Institute for Conservation. The award recognizes a sustained record of excellence in the education and training of conservation professionals. The award was presented in Los Angeles on May 14, 2022, during the Fiftieth Annual Meeting of the American Institute for Conservation.

The American Institute for Conservation is the leading membership association for current and aspiring conservators and allied professionals who preserve cultural heritage. Its mission is to support conservation professionals in preserving cultural heritage by establishing and upholding professional standards, promoting research and publications, providing educational opportunities, and fostering the exchange of knowledge among conservators, allied professionals, and the public. ■

Sarah Beckmann Awarded Rome Prize Fellowship

Sarah Beckmann, an assistant professor of classics and a core faculty member of the Cotsen Institute, has been awarded a 2022 Rome Prize Fellowship in ancient studies for her work on “The Villa in Late Antiquity: Roman Ideals and Local Identities.” The highly competitive fellowship supports advanced independent work and research in the arts and humanities, according to an April 2022 announcement by the American Academy in Rome, which describes the award as “the gift of time and space to think and work.”

Each fellow receives a stipend, workspace, and room and board at the 11-acre campus of the academy on the Janiculum Hill in Rome, starting in September 2022. “These fellowships are transformative, and we look forward to seeing the ways this experience is translated in the work to come,” according to Mark Robbins, president and chief executive officer of the American Academy in Rome. Beckmann’s award was described as “a stunning achievement” by Alex Purves, a professor and chair of the Department of Classics at UCLA.

“I am delighted to be next year’s recipient of the Andrew Heiskell Rome Prize,” Beckmann said, noting that the prize will “allow me to spend the 2022–2023 academic year in residence at the American Academy in Rome.” She will work on her first monograph, focused on late antique villas. Beckmann describes the first part of the book as looking at architecture and decor, focusing on regional variations of so-called elite display traditions. Part two of the book moves beyond villa owners, analyzing evidence for estate laborers, both as “actors in their own right and as pawns in the promotion of the villa into a status symbol.”

On a more personal level, “I am absolutely delighted to return to Rome,” Beckmann added. “I studied there in college, and it was that experience that started me on my studies toward a PhD in Roman archaeology. Years later, I am incredibly lucky to be returning. I will be writing my first book but also touring around a bit to gather material for my second book project. And of course I am excited to revisit my old favorite places and find new ones. I am really looking forward to updating my images of major monuments and sites in and around Rome” for a class on Roman archaeology that she teaches every year at UCLA.

“I cannot wait to work alongside scholars from different disciplinary backgrounds,” she continued. She

described the opportunity presented by the Rome Prize as offering “time to think and write in a creatively stimulating environment with others whose work touches on or is in dialogue with Rome as a place or an ideal.”

Beckmann will be joined by her family, including her one-year-old son and four-year-old daughter. “I feel very lucky to bring them all, and I am looking forward to time off from writing to watch my son learn to walk on the cobblestones, sharing gelato with my daughter, and watching her Italian surpass my own, as well as spending a year in the magical city where my partner and I spent our honeymoon.”

Rome Prize winners are selected annually by independent juries of distinguished artists and scholars through a national competition. Beckmann continues a tradition of Cotsen Institute awardees, following in the footsteps of core faculty member Ellen Pearlstein, a professor in the Department of Information Studies and the UCLA/Getty Conservation Program, who received a Rome Prize in 2021–2022. ■

Justin Dunnavant Welcomed as Scholar in Residence at Occidental College

Justin Dunnavant, an assistant professor of anthropology and a core faculty member of the Cotsen Institute, has been honored with the 2022 Stafford Ellison Wright Black Alumni Scholar-in-Residence Award from Occidental College in Los Angeles. His residency took place through online lectures and presentations on February 16 and 17.

The Stafford Ellison Wright Endowment supports “select esteemed scholars whose work on Black life and culture has made a significant contribution and whose research will excite and engage the entire Oxy community,” according to Occidental College president Harry J. Elam Jr., who introduced the first lecture. Created by the Black Alumni Organization at Occidental College, the endowment honors its first Black graduates from 1952: Janet Stafford, George F. Ellison, and Barbara Bowman Wright. The residency is by invitation only and includes a financial award.

As part of his residency, Dunnavant gave a public lecture, “In Search of Maroon Geographies: Archaeologies of African Fugitivity in the Virgin Islands,” and participated in a panel discussion: New Approaches to Caribbean History and Heritage. Regina Freer, a professor of politics and a member of the Stafford Ellison Wright Committee, praised him for “exploring the remains of shipwrecks to investigate the ecological effects of the slave trade with an eye towards current-day connections.” She added, “His work is community-connected and he is passionate about training future maritime archaeologists. We are so excited to have him with us.”

Dunnavant described his approach to the Maroon geographies lecture as being “from the water perspective and GIS perspectives.” His second lecture “was framed toward an intergenerational conversation,” he said. “The mentor I was in conversation with, Dr. ChenziRa Davis Kahina,” has been working in Black studies since the 1980s “and is able to look at it from a historical perspective.”

He also addressed two classes, one in biology and the other in African American studies. To prepare for those presentations, he got syllabi from the respective professors, so he knew “what they’ve been talking about and what they’ve been reading.” Because he does so much interdisciplinary work, “I try to tailor

my conversation around the disciplines that they are coming from. So for biology, we’re talking about ecological work, about coral science and coral mining.” He also tries to explain to students that many of these fields fall within anthropology and archaeology. “I’m sort of trying to get them to convert over,” he said.

His recruitment of young people into anthropology and archaeology began with his work in the Virgin Islands, where he started a youth training program. “We take middle and high school–age kids and teach them archaeology. So from that, we’ve adopted this mind-set where everywhere we go, we have to be able to translate the work we do to a younger audience. And that was something I’ve been adamant about. Before coming to UCLA, I was interviewed for a series on Hulu, in which my work was shown as an animation. I wanted something that would attract young people, not only to my work but also to the fields that I explore.” ■

Justin Dunnavant

Attends

Artifact Analysis Workshop in Monticello, Virginia

In the summer of 2022, Justin Dunnavant, core faculty member of the Cotsen Institute and a 2022 NEH Digital Archaeological Archive of Comparative Slavery Fellow, attended a monthlong intensive workshop for the analysis of colonial ceramics, glass, metals, and small finds, held in Monticello, Virginia. The workshop aimed to facilitate uploading archaeological data into an online, open-source database that will allow for cross-site comparisons of archaeological sites related to slavery. ■

Two Cotsen Institute Alumnae Accept Tenure-Track Positions

Carrie Arbuckle MacLeod and Debby Sneed, both of whom earned PhD degrees from the Cotsen Institute in 2018, have recently accepted tenure-track positions. Arbuckle MacLeod is now an assistant professor of classical and Near Eastern archaeology at St. Thomas More College at the University of Saskatchewan, Canada, and Sneed is an assistant professor of classics at California State University–Long Beach.

The alumnae agree that hard work and perseverance are major contributors to their success. Sneed explained, “There really is no key to success in academia. You can do everything you are told to—publish in the right journals, teach in the right departments, communicate with the right people—and still not land a tenure-track position.” Her priority is “to focus on doing what I find fulfilling about this work, without fixating on trying to work within a system in which there are no guaranteed outcomes. For example, I have tried to focus on writing the articles that I wanted to write, not those I thought would get me the most mileage in the job market, because I didn’t want to regret neglecting what I’m passionate about.”

Sneed will primarily teach ancient Greek to undergraduate students, as well as courses in ancient Greek and Roman myth, culture, history, and archaeology. She also plans to develop a new course on disability in the ancient Mediterranean world. Sneed had been a lecturer in the same department since January 2020. She said, “I got my current position because of terms outlined in the new collective bargaining agreement negotiated by the California Faculty Association, which represents faculty in the California State University system.” She advises current students and recent graduates to unionize.

Since receiving the Ben Cullen Prize for an article published in Antiquity, Sneed has completed a research fellowship at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, where she was from January through August of 2022. She also published an article on disability and infanticide in ancient Greece in Hesperia and submitted other articles scheduled for future publication. She is in her second year as a lecturer for the National Lecture Program of the American Institute of Archaeology and is working on additional projects, including a book about disability and daily life in ancient Greece, an article about disability and religious practice in archaic Athens, and an article about assistive technology in the ancient world.

Two Cotsen Institute Alumnae Accept Tenure-Track Positions (continued)

Arbuckle MacLeod is originally from Vancouver, Canada, and was interested in finding a position in Canada. Before obtaining her PhD from the Cotsen Institute, where she taught the course Archaeology in the Digital Age, she completed her BA in classical and Near Eastern archaeology at the University of British Columbia and her MA in Egyptology at Oxford University. After graduating from UCLA, she returned to the University of British Columbia, where she spent four years in a postdoctoral position teaching ancient Egyptian archaeology, religion, and language courses and working as an editor for the Database of Religious History. Together with Danielle Candelora, also a UCLA alumna, she is codirector of a short undergraduate teaching program at Museo Egizio in Turin, Italy.

As an archaeologist who specializes in the study of ancient Egypt, she is interested in understanding the lives and techniques of ancient Egyptian carpenters. She studies the long history of coffin construction in ancient Egypt to understand better how carpenters adapted their techniques to political, environmental, and religious shifts. She is also frequently involved in public history and digital humanities projects, particularly those related to archaeology and digital games. Regarding teaching, she says that “creating a welcoming learning environment should be the first goal of every instructor. When students feel confident that their voices will be heard, discussions are more productive and both students and instructors will gain greater enjoyment from the experience.” She teaches the courses Introduction to Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology and Introduction to Egyptian Archaeology. She has also proposed a course on her

subspecialty: Introduction to the Archaeology of Wood and Woodworking.

Arbuckle MacLeod found the call for applications for her current position on Indeed.com, but she also subscribed to many listservs and maintained contacts at UCLA and elsewhere, through which she would get updates on different openings for positions. She points out that there were “maybe five or six openings every year that I was suited for, and there may have been hundreds of people applying. Last year I think I applied for five positions. You find out pretty quickly that you are one of many very qualified candidates. It really just depends on what the position calls for. For my current job, the call was open to scholars in Greek, Roman, the Near East, and Egyptian specialties. So I thought I had a foot in there.”

She continued, “In the United States, the job postings often say that priority is given to American citizens. It was the same thing here: priority was given to Canadian citizens. I had a postdoc that they were willing to extend to a third year if I wanted, so I was only applying for jobs that were tenure track.” She mentioned things that need to be done to make sure your CV is competitive: publish, teach, present at conferences, and so on. “But everybody is doing that. So I would say it is about 30 percent that and 70 percent luck, quite frankly. I know it gets very disheartening when you apply for these things and you don’t even make it to the final round, thinking that there is something wrong with you or your CV. Usually it is just that there is a really specific gap that they are trying to fill, and you don’t happen to fill that gap.” She concluded, “It is just a matter of persistence.” ■

Vanessa Muros Awarded Boochever Endowment

Vanessa Muros has been awarded funds from the Kathleen and David Boochever Endowment for Fieldwork and Scientific Analyses by the Archaeological Institute of America. The endowment supports fieldwork or laboratory research informed by new technologies. Muros is director of the Experimental and Archaeological Sciences Laboratory at the Cotsen Institute.

The project for which she received the award will test the efficacy and reliability of two low-tech methods: ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence and the Raspail test, a microchemical test for plant terpenoids to analyze organic residues in pottery in the field.

Muros will first run tests on ceramic tiles she will make in the laboratory. Based on the results, she will use the developed methods on pottery from ancient Methone in northern Greece when she works in the field in summer. A conservator on the Ancient Methone Project, she is responsible for the preservation of the excavated materials. She is mainly focused on the conservation of artifacts (ceramics, metals, stone, glass, bone, and ivory) but also helps other team members with research on the excavated material.

“Part of the work that I do in terms of conservation and research is materials identification,” she explained. She is often asked to help archaeologists identify residues found in excavated ceramic vessels. “Sometimes we can bring portable analytical instruments to the field for more sophisticated characterization of materials, such as with the portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometer. Most of the time, however, we need to rely on low-tech methods that we easily can use in the field.”

She has already been using ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence and the Raspail test for the identification of residues but says that some work from the Arizona State Museum showed that the analysis is not consistent. “Because I was relying on these techniques in the field, I thought it would be important to set up systematic testing of the methods to check how consistently either can be to identify the types of organic materials that we may be looking for on the excavated material at ancient Methone. To do this, I am now creating a set of ceramic tiles that I will be coating with different materials (pine resin, mastic,

beeswax, and birch bark tar), and then I’ll analyze the resins using both methods. The thickness of the coatings will vary, so I can see how this affects my identifications.”

She added, “I also am going to artificially age a set of coated tiles to see if that has any impact on the results. The goal is to understand how the two methods respond to the materials and how consistent they can be if the residue thickness changes or the material is aged and deteriorated. The results of the tests will be used to determine how best to apply these methods on the ceramics I will be examining this summer at Methone.” ■

Cotsen Affiliates Present at Congress in Turin, Italy

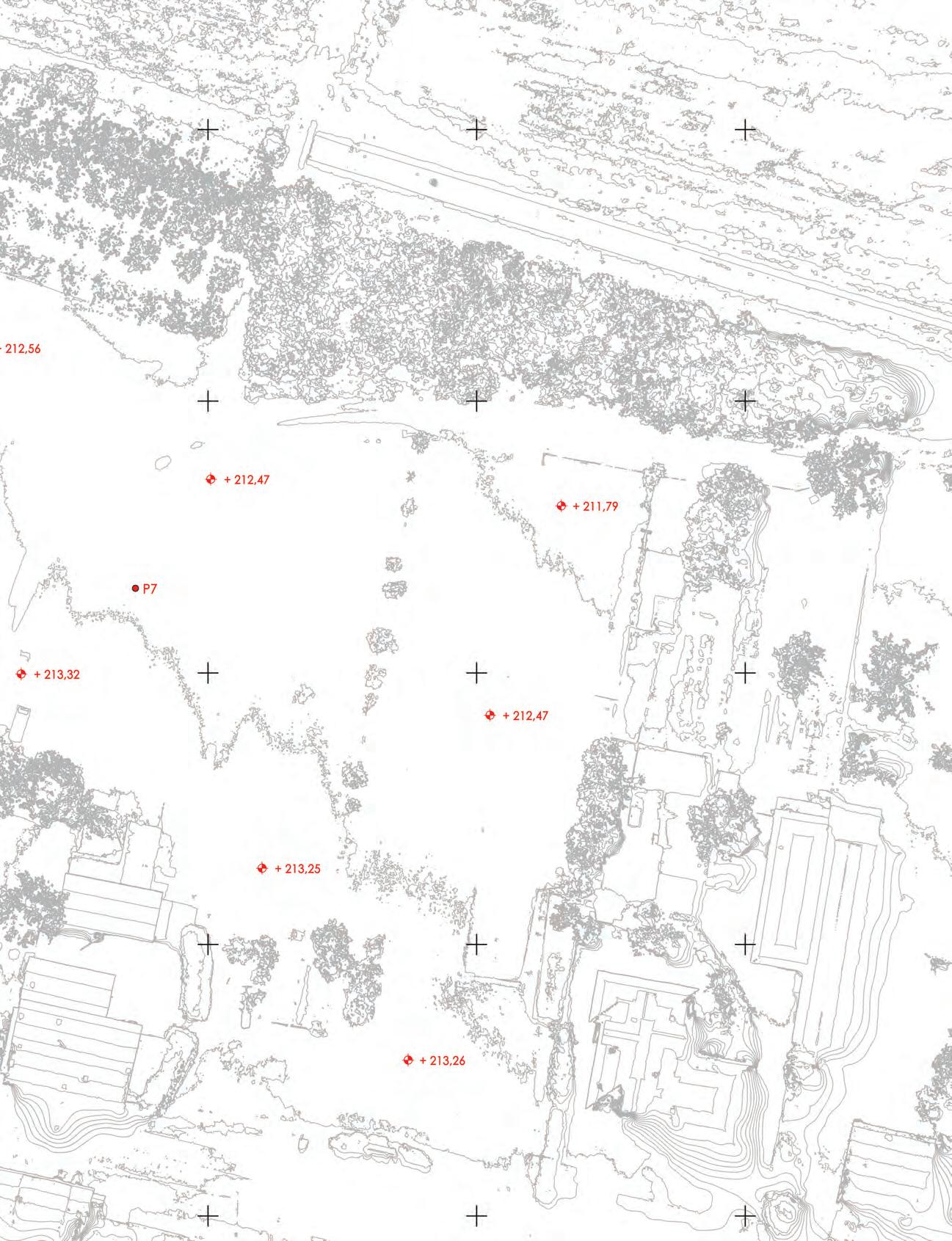

Willeke Wendrich, director of the Cotsen Institute, and UCLA graduate students Brandon Keith, Iman Nagy, and Matei Tichindelean presented their research at the tenth congress of the Italian Association of Urban History, held September 6–10, 2022, in Turin, Italy. The association aims to promote the study of urban history. The theme of the congress was “Adaptive Cities through the Postpandemic Lens.”

Nagy, who presented by recorded video, and Tichindelean are both graduate students in the Cotsen Institute. Keith is a graduate student in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures. Their presentation was “Construction, Destruction, and Reconfiguration of the Ritual Landscape of Philae (Egypt)” and was part of the session Expressing the Longue Durée, 3D Modeling Change Over Time, co-organized by Wendrich and Elaine Sullivan, currently at UC Santa Cruz and a former postdoctoral

researcher at UCLA. Wendrich presented in the plenary session Controversial Adaptivity and reported on the session Interactions between Humanity and the Environment in the Long Durée. Keith, Tichindelean, and Wendrich are currently involved in archaeological fieldwork just east of Turin.

The Italian Association of Urban History is one of the most active Italian cultural associations and is concerned with the history of cities. It enjoys strong institutional support from universities, research centers, and cultural institutions, as well as broader academic engagement. Because the history of cities is multifaceted and plural, the association is multidisciplinary, inclusive, and international. It is in this context that the association seeks to promote scientific research and interdisciplinary and cross-sector dialogue; to stimulate debate in civil society; and in particular to support the many young researchers who attend the various activities it organizes every year. ■

Gregson Schachner, Reuven Sinensky, and Katelyn Bishop Contribute to Book Honored by the SAA

Christopher Donnan Publishes Book on a Royal Moche Tomb

The Society for American Archaeology (SAA) has named Becoming Hopi: A History the recipient of its 2022 Scholarly Book Award. The book, published by the University of Arizona Press, was coedited by Wesley Bernardini, Stewart B. Koyiyumptewa, Gregson Schachner, and Leigh J. Kuwanwisiwma. Schachner, an associate professor of anthropology and former chair of the Interdepartmental Archaeology Program; Reuven Sinensky, a doctoral student in anthropology at UCLA; and Katelyn Bishop, a UCLA graduate in anthropology and now an assistant professor at the University of Illinois UrbanaChampaign, coauthored multiple chapters in the volume.

The SAA announcement commended the book as follows: “Becoming Hopi shows a masterful interwoven collective work of conventional archaeological data and Hopi traditional knowledge to carefully study the Hopi Mesas of Arizona. In this volume, the voices of the Hopi are integrated with archaeological and ethnographic work conducted over two decades to show an important Indigenous group of the American Southwest with its rich and diverse historical tradition dating back more than 2,000 years. This tradition is deeply rooted in time, and the voices of the Hopi can be heard by scholars and non-experts. In addition, the collaborative effort resulted in a book that can be used by members of the Hopi community to learn about their own past.”

Schachner was also an editor, together with Richard Wilshusen and James Allison, of Crucible of Pueblos: The Early Pueblo Period in the Northern Southwest, which was published by the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press in 2012. This volume received a Choice 2013 Award for Outstanding Academic Title. ■

Christopher B. Donnan, a professor emeritus of the Department of Anthropology at UCLA and former director of the Andean Laboratory at the Cotsen Institute, has published La Mina: A Royal Moche Tomb (University of New Mexico Press). The book includes more than 200 color images of archaeological treasures unearthed at La Mina, an “extraordinarily rich tomb that was looted on the north coast of Peru in 1987,” according to the publisher. Joanne Pillsbury, editor of Moche Art and Archaeology in Ancient Peru, calls the book a “monumental achievement and an incomparable contribution to the field of Andean archaeology and art history.”

For more than 50 years, Donnan has studied the Moche civilization, which flourished between 100 and 700 CE in northwestern Peru, combining a systematic analysis of Moche art with numerous archaeological excavations. He is the author of several monographs from the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, including Chotuna and Chornancap: Excavating an Ancient Peruvian Legend (2012) and Moche Tombs at Dos Cabezas (2007). He is a coauthor of several other publications by the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, including The Pacatnamu Papers (1986), written with Guillermo A. Cock, and Moche Fineline Painting from San Jose de Moro (2007), written with Donna and Donald McClelland. ■

Transformation of a Sacred Landscape around Lake Gilli, Armenia

Lake Gilli (also known as Lake Zodi, Tilli, Mazrayi, or Jili) and its basin once formed a unique ecological environment southeast of Lake Sevan in the Masrik Valley, Armenia (Figure 1).3º Lake Gilli was a shallow and swampy lake with a circumference of about 7.5 km (4.5 miles), surrounded by lush reed vegetation. Three rivers—the Akanic’, Karmir aġbyowr, and Kaler—once flowed into the lake. The Masrik River passed through it and flowed into Lake Sevan. Lake Gilli sustained unique flora and fauna, especially birds, but dried up completely in the mid-twentieth century due to the artificial lowering of the water level in Lake Sevan.4

The Gilli Reserve was later established to preserve the remaining swamps, along with the aquatic vegetation and endemic fish species in Lake Sevan (Figure 2; Ananyan 1952, 1961–1975; Hakobyan et al. 1986:863). This unique ecological niche has been a source of various

1. Director, Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia.

2. Director, Armenian Laboratory, Cotsen Institute.

3. Archaeological surveys on the eastern shores of Lake Sevan are realized under the auspices of the National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia and the Scientific Committee (Grant 21AG-6A080). They are partly supported by the Research Program in Armenian Archaeology and Ethnography at the Cotsen Institute.

4. The artificial drying of Lake Gilli began in 1959–1960. In 1978 the Armenian government decided to establish Sevan National Park and restore Lake Gilli within the park area. Studies on the restoration of Lake Gilli and project work resumed in 2000. The restoration program was presented as a global biodiversity conservation issue (Government of the Republic of Armenia 2002). In 2003 the government issued a restoration of Lake Gilli postage stamp (no. 285; designed by Albert Kechyan).

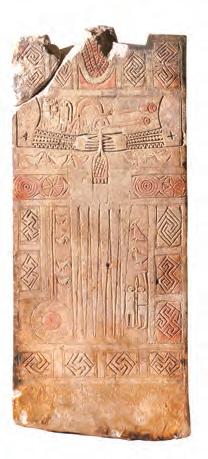

folk tales and legends. These are best summarized in Vakhtang Ananyan’s 1951 novel On the Shore of Lake Sevan, which was later adapted into a film.5 According to legend, a dragon lived in the lake; roars and growls regularly heard from the lake were attributed to the dragon. For inhabitants of the Armenian highlands, the various folk tales, stories, and worldviews concerning dragons have long been associated with monolithic steles called višapak‘ar (dragon stones), which depict animal forms and images with specific symbolic meanings indigenous to the highlands (Ananyan 1952:17–18; Bagoyan 2019:269; Hovhannisyan 2019:80; Petrosyan 1987:64, 2015:14; Simonyan and Hovhannisyan 2019:170). The monuments, located between 1,200 and 3,000 m (4,000–10,000 feet) above sea level, date to the Middle and Late Bronze Ages (2300–1200 BCE). In Armenia, the two main višapak‘ar clusters are on Mount Aragats and in the Geghama mountain range (Hnila et al. 2019).

Višapak‘ar have long been associated with dragons

Very little archaeological and ethnographic research was carried out in the Gilli Basin during the pre-Soviet and Soviet years (before 1991), primarily because the region was unwelcoming to researchers for ethno-political reasons (Smbateants 1895:631). Among the few studies of importance are the works of Yervand Lalayan and Sedrak Barkhudaryan, who studied the history, population, and monuments of the villages around Lake Gilli, in particular Geġamasar (Šiškaya), during the first half of the twentieth century (Barkhudaryan 1973:311–12; Lalayan 1910:21–30). More systematic research in the region, under the auspices of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia, began after independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. This article presents some of the results of this research, detailing historical processes of the transformation of the area from a pre-Christian to a Christian sacred landscape, as exemplified by Spitakavor Church in the village of Geġamasar.

et al. 1986:863), though some have proposed a connection to the archaic root geġ-, the basis of many historical toponyms of Geġark’ownik’ (Petrosyan 2015:14). Indirect information on the history of the Gilli Basin appears in various publications about the Lake Sevan Basin or Sotk’ Province. From these texts we know that during the Middle Ages (the fourth through eighteenth centuries CE), the Gilli Basin was within the province of Sotk’ (Alishan 1893:63–76; Grigoryan 2020:186–206; Orbelean 1910:514–15).

Historic sources and archaeological excavations in recent years show that the Lake Gilli Basin, and the region in general, reached its peak of urban development in the Middle Ages, when spiritual and secular infrastructures, defense systems, and settlements preserved from the previous periods were renovated, restored, and actively used. The single-naved Spitakavor Church (also known as Akk’ilisa, Axilisa, or Ag-Gilisē),6 located on the former shore of Lake Gilli, 4 km (2.5 miles) to the southwest of the village of Geġamasar, is first mentioned by Ghevond

There is very little information about Lake Gilli in medieval sources. The name is probably connected with the adjacent settlement of Gil (Basmajean 1927; Hakobyan

Alishan (1893:75), who writes, “On the shore by Šišgaya is the old church Ag-Gilisē, perhaps also a monastery, which is otherwise not known to me.” Yervand Lalayan (1910:24), describing the valley in front of the village of Šišgaya, which stretches for about 3 km (2 miles), writes that there is “a half-ruined small church here; there is a large xačk’ar (cross-stone) within it which bears a distorted epigraphic inscription” (Barkhudaryan 1973:311). Archaeologist Hovsep Yeghiazaryan (1942:5) mentions a medieval settlement around the church under the cultivated fields and notes the presence of pottery fragments dating to the tenth through thirteenth centuries CE. A church with the name Akkilisa also appears on Soviet maps.7

To date, our team has not found any information about the construction date of the church. However, its historical-archaeological context provides a rough estimate.8 Spitakavor Church is situated on the edge of a flat area, 1,929 m (6,329 feet) above sea level (Figures 3 and 4). Before excavavations, it was filled with soil and garbage (Figure 5). In 2021 the Sotk’ expedition of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography carried out excavation, conservation, and restoration work at the church under the direction of Avetis Grigoryan. After cleaning, it became clear that the church is a single-naved building with a rectangular plan (6.1 x 4.3 m [20 x 14 feet]; Figure 6). At one point, it had a vaulted roof, which has not been preserved. It is built of locally sourced, unworked white marl limestone and river stones, bonded together with lime mortar. Large chunks of conglomerates—sediments of fossilized lake sandstone—were also used in the wall masonry.

Entrance to the church is from the west (Figure 7). Twin windows have been preserved on the east facade, and there are small niches on the northern and eastern walls, one on each side. Slightly to the west of the north–south axis of the church, the remains of a vaulted arch have been preserved. The lower parts of the vaulted arch extend down the wall along a pilaster but do not reach the floor, ending 0.5 m (1.5 feet) above it. The inner facades of the church walls and the floor were lime plastered and have been preserved in some areas. It is perhaps because of the lime plaster that local Muslim populations called the church ag-Gilisē (the White Church). On the western side, a fragment of a wall abutting the church suggests that there used to be an anteroom, only the southern wall of which has been preserved. This structure, made with a much simpler construction technique, with walls having an earthen filling, was probably a later addition. The eastern part of the church is divided into two parts by a low partition wall (height and length about 0.9 m [3 feet]), separating the area into two niches, which probably served either as prayer rooms or as sacristies. In each niche, a centrally placed window would have lit the area.

There is little about Lake Gilli in the medieval sources

One fragment of a višapak‘ar (dragon stone) remodeled into a xačk’ar (cross-stone), discussed in more detail below, was likely the main sacred object of the church. It stood upside down (from the perspective of the višapak‘ar) in the center of the church. Examination of the placement and measurements of the fragment indicates that it also served an architectural function as a pillar bearing the load of the vaulted ceiling over that section of the church.

Excavations revealed a clay-plastered floor, which was preserved throughout the interior, apart from the area immediately around the višapak‘ar-xačk’ar (a dragon stone remodeled into a cross-stone), where the floor was damaged when the stone was embedded into it. The lower fragment of another finely carved xačk’ar was found near the entrance of the church, embedded into the lower masonry of the outer wall (Figure 8). The fragment depicts interlaced patterns and a pair of pigeons facing one another under a palmetto. The pigeons probably symbolize those who prayed for the salvation or intercession of the soul of the deceased. Based on the characteristics of the iconography, this xačk’ar should date to the thirteenth century (Figure 9; Petrosyan 2008, 294–97). Inside the church, near the

entrance, three reliquaries filled with ashes were found. The middle one was built with roughly worked slabs, the western one was simply dug into the ground, while four roughly rectangular stones with furrows were used to line the walls of the eastern reliquary. The latter stones likely belonged to an older structure in the vicinity. The reliquaries were looted, so the details of their initial contents remain unknown (Figures 8 and 9).

With its architectural design (Figure 10), Spitakavor Church has a number of parallels in the eastern basin of Lake Sevan, such as a small church on the eastern peak of Šorža, the Ada Monastery on the Artaniš Peninsula, the church of Gill, the St. Astvaçaçin (Mother of God) and St. Gevorg Churches of Ayrk’, and others. In Arc’ax, parallels include the old part of the single-naved Basilica of Hoṙekavank’, the churches of Jrvštiki, the Monastery of the Apostle Eġiše, and the church-tomb of Vačagan the Pious (Ayvazyan and Sargsyan 2013:1–11; Barkhudaryan 1982:104–5). It cannot be excluded that Spitakavor Church could have been a church-tomb. Judging from the architectural elements of the church and the geopolitical environment of the region, the church was most likely constructed in the sixteenth or seventeenth century. The discovery of building stones of

secondary use within Spitakavor Church, an assortment of pottery dated to the thirteenth through fifteenth centuries, a fragment of an ornately decorated xačk’ar, and an inscription on the višapak‘ar-turned-xačk’ar attest to the existence of an earlier sanctuary here, on the base of which perhaps the present church-reliquary was built. Spitakavor Church fell out of use sometime in the second half of the nineteenth century, when the region was emptied of its Indigenous Armenian population (Smbateants 1895:592–631).

The thick wall constructed of roughly worked, large stones that surrounds the church was part of the medieval landscape of Spitakavor (Figure 6). In its style and masonry, it is more like Bronze and Iron Age structures in the vicinity. Stone structures of indeterminate use found within the parameters of the wall, a roughly worked stone with a simple cross carved on one face found near the northern wall of the church, and a primitive xačk’ar bearing a cross with two-lobed wings, typical of the ninth and tenth centuries, were part of the medieval church complex. The latter is now around 1.5 km (1 mile) northeast of Spitakavor, in the middle of a field, near a large apple tree. It is now a sacred place and frequently visited by locals.

The xačk’ar was erected in the center of Spitakavor Church and, at the time of our visit in 2020–2021, was broken into three fragments. Village inhabitants recently placed one fragment in front of the entrance to the church. One of the two fragments that remained within the church leaned against the eastern wall. The other fragment was embedded in the floor of the church (Figure 5). Two of these fragments show a relief of a cross erected on a stepped pedestal, linear crosses on the lateral faces, and an Armenian inscription (Figures 11 and 12). The arms of the main cross have a simple double-branched ending, with each branch ending in three spheres. This is one of the earliest examples of the transition from two spheres to three spheres typical of the early iconography of the cross.9 The stepped pedestal into which the cross was placed, as a rule, symbolizes not only the important, sacred status of the cross in Christian art but also the hill of Calvary (Golgotha), on top of which stood the

cross used for the crucifixion of Jesus Christ (Petrosyan 2008:278.) The symbolism of a stepped pedestal and a circular rosette, not present on this xačk’ar, is usually the same. Thus in the presence of a stepped pedestal, a rosette is absent and vice versa (Petrosyan 2008:279).

The inscription, with its asymmetric letters and lines, gives the impression that an inexperienced hand carved

them into the xačk’ar (Figure 13). The average height of the letters ranges between 10 and 15 cm (4–6 inches). The inscription consists of nine lines and was carved to the right of the cross, near the bottom of the xačk’ar. Yervand Lalayan (1910:24) wrote, “I found out only the year 1251.” More than half a century later, Sedrak Barkhudaryan (1973:311), in his discussion on the history of the region, quoted Lalayan; thus we assume that he did not see the xačk’ar himself. The inscription was finally deciphered in 2021 by Arsen Harutiunyan, who also noted that Lalayan had misread the 1251 date The inscription, which is published here for the first time, reads: “The Holy Cross was erected in memory of Abgar’s son, Gregory and the latter’s son, let them be remembered in glorifying God, 936.”

The višApAk‘Ar Turned in T o A XAčk’Ar

During initial examination of the stone in 2020, our team noted that certain characteristics—such as the style of processing the stone and the type of rock—are more typical of pre-Christian steles. A detailed examination of the individual fragments revealed an outline of a bull’s head carved onto one of them. It became clear that the fragments once formed a complete, even if not finely executed, bull-headed višapak‘ar. The stele is not described as a višapak‘ar in any historical texts dealing with the region or this monument in particular. Despite having been broken into three pieces, the stele is relatively well preserved. When joined it measures 360 x 107 x 55 cm (142 x 42 x 22 inches). The freestanding fragment measures 123 x 85 x 46 cm (48 x 33 x 18 inches), the fragment inside the church is 137 x 104 x 50 cm (54 x 41 x 20 inches), and the

fragment embedded in the ground is 115 x 107 x 55 cm (45 x 42 x 22 inches). Although the relief is incomplete, a bull’s head and front legs can be made out on the obverse of the stele (Figures 11 and 12).

One question is whether the višapak‘ar-turnedxačk’ar is in its original location or was moved to its current location from elsewhere. At present this question cannot be answered with any certainty. The wall surrounding the church is typical of megalithic structures of the Bronze Age, such as cromlechs and Cyclopean structures, made during a period when višapak‘ar steles

became widespread in the Armenian highlands. It is thus possible that the višapak‘ar is in its original location and was placed on a small hillock or a barrow, which was there until Spitakavor Church was built. However, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that the stele was brought to its current location from the surrounding plain sometime during the Middle Ages. The area around the village of Geġamasar is famous for various Bronze and Iron Age sites, as well as for a Cyclopean fortresssettlement (Biscione et al. 2002:63–65). From the point of view of secondary use, in addition to the already

mentioned crosses and inscription, there are cup-marks on two of the fragments of the višapak‘ar. 10 These are often found on višapak‘ars and were often made after the fall of a monument, likely during the Iron Age.

From the description of Yervand Lalayan above, it is clear that during his visit in the first years of the twentieth century, the “big xačk’ar” was standing in one piece and was not broken. The break must thus be recent, likely dating to the Soviet period (1922–1991), when the church was closed and filled with debris. According to a local inhabitant, in 2010 only the upper part of one of the freestanding fragments was visible on the surface. It was cleared, removed, and placed in front of the church as a xačk’ar, while the second stone was cleaned by the villagers in 2015 and was left inside the church (personal communication with Gurgen Abrahamyan, resident of Geġamasar). After excavation of the church and its surroundings, the three fragments were joined by our team in 2021 and placed to the east of the church (Figure 6).

Petrographic analysis of the rock of the višapak‘arxačk’ar to determine its mineral composition was undertaken by Arshavir Hovhannisyan of the Institute of Geological Sciences of the National Academy of Sciences of Armenia. The sample was taken from the central part of the višapak‘ar, directly from the edge of the broken fragment, away from the face of the stele. Analysis determined that the rock is an andesite-basalt, with 1.5, 2, and

3.5 mm–long crystals of long prismatic hypersthene, rich in mineral inclusions and micro-dendrites. Based on these characteristics, the raw material used to carve the stele can be sourced to the Quaternary-period andesite-basalt lava flows of the Geghama and Vardenis mountain ranges. A defining feature of the višapak‘ar rock is the adhesion of biotite crystals to the walls of its pores. This is typical of the lava flows of P’orak, a volcano in the Vardenis mountain range. The lava flows of P’orak reach the southern shores of Lake Sevan and occupy a significant area. These lava flows are the closest to the current location of the višapak‘ar, 13 km (8 miles) in a straight line across the lake. If we take into account that the water levels in Lake Sevan were 15–20 m (50–65 feet) higher at the time of the creation of the višapak‘ar and that the current location of the višapak‘ar then also must have been on the shore of Lake Sevan, then the most optimal route for transporting the višapak‘ar, or its raw material, to Spitakavor was across Lake Sevan (Figure 14). Alternatively, the višapak‘ar could have crossed a land route of about 25 km (16 miles) through unfavorable terrain. In all probability, rafts were used to transport the rock across the lake to its final destination, where it remained for centuries until it was appropriated, remodeled, and incorporated into Spitakavor Church.

d i SC u SS ion

Lake Gilli was a unique ecological environment in ancient times and became an important and sacred center of collective memory. The višapak‘ar, or its raw material, was likely brought to its current location at Spitakavor, across Lake Sevan from the lava flows of Mount P’orak, sometime during the second millennium BCE. During the first half of the tenth century, the stele was remodeled into a xačk’ar by adding symbols typical of Christian iconography, mostly crosses of various types. An inscription haphazardly carved near the central cross identifies the time of the event and the persons associated with it. A few centuries later, probably during the sixteenth or seventeenth century, a church-reliquary was built around the xačk’ar, so it appeared in the center of the structure, serving a dual purpose as both a sacred object and a pillar supporting the vaulted roof.11

11. A remarkable historical-ethnographic parallel of this connection between pre-Christian and Christian monuments is known from the Javakheti region in Georgia. At the end of the nineteenth century, local Armenians worshipped a stone measuring 1 m (3 feet) in length on the top of Mount Great Abuli, under which a saint was said to be buried. According to legend, previously the idol of Apollo was on Mount Great Abuli, from which the name Abuli may have derived (Melikset-Bekov 1938:117; Rostomov 1898:23–24).

Spitakavor Church probably fell out of use in the second half of the nineteenth century, when the region was emptied of its Indigenous Armenian population. According to modern accounts, the višapak‘ar-xačk’ar was broken during the Soviet period, though it is unclear if this was an intentional act or an accident. During the earliest appearance of xačk’ars, in the ninth through eleventh centuries, many pre-Christian and early medieval steles, including višapak‘ars, were remodeled into xačk’ars by carving a cross or crosses into them. Inscriptions were often added to commemorate those who had commissioned or carved the cross-stones (Harutyunyan 2019:504). The probable reason for such a phenomenon was the destruction of pagan steles, viewed as a form of idolatry, through application of a cross (Muradyan 1985:22–23), although, in the case of višapak‘ars, the destruction was a symbolic one, as the parameters of steles were ideal for turning them into xačk’ars. That is, in the early years, when xačk’ars began to be created and used, višapak‘ars were perceived as ready-made steles that could be repurposed by simply carving Christian symbols—crosses, rosettes, birds, palmettos, stepped pedestals, and so on—into them.12

One more reason can be singled out in the context of the stability of collective memory. In particular, in the case under discussion, the act of turning a višapak‘ar into a xačk’ar after the adoption of Christianity and the act of “destruction” of a višapak‘ar-turned-xačk’ar after the appearance of non-Christian nomadic tribes in the region clearly illustrate points of connection and breaks of collective memory and value systems during transformation of the sacred landscape. The nomads broke the višapak‘arxačk’ar, destroyed the church, covered it with soil, and actively leveled the surroundings, trying to cover up the existence and long history of the sanctuary as much as possible (for similar cases, see Korkotyan 1932:26–7, 112–13) This implies a radically different approach to perception of space compared to the former Indigenous population. Though the natives did not have a direct memory of the makers of the višapak‘ar, they nevertheless felt a connection to the sacred space and perhaps even the stele. It is also not by chance that the axis of visibility of the višapak‘ar-xačk’ar is Mount Aragats, which is visible beyond Lake Sevan and is home to the highest accumulation of višapak‘ars on the Armenian Plateau.

The three fragments were joined by our team in 2021

r eferen C e S Ci T ed

Alishan, Ghevond. 1893. Sisakan: Topography of the Syunik Region. [In Armenian.] Venice: St. Lazarus.

Ananyan, Vakhtang. 1952. On the Shores of Lake Sevan. [In Armenian.] Yerevan: State Publishing House.

–——. 1961–1975. Fauna of Armenia: From Ancient Times to the Present Day, vols. 1–5. [In Armenian.] Yerevan: State Publishing House.

Ayvazyan, Samvel, and Gagik Sargsyan. 2013. Excavations of Horekavank “Vardsk.” [In Armenian.] Foundation for Research on Armenian Architecture 9:1–11.

Bagoyan, Alla. 2019. Motif of Dragon in the New Armenian Literature. In Vishap between Fairy Tale and Reality. [In Armenian.] Edited by A. Bobokhyan, A. Gilibert, and P. Hnila, pp. 257–72. Yerevan: Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, National Academy of Sciences.

Barkhudaryan, Sedrak. 1973. Corpus of Armenian Epigraphy. Vol. 4, Gegharkunik: Regions of Kamo, Martuni and Vardenis. [In Armenian.] Yerevan: National Academy of Sciences.

———. 1982. Corpus of Armenian Epigraphy. Vol. 5, Artsakh. [In Armenian.] Yerevan: National Academy of Sciences.

Basmajean, Karapet. 1927. New Armenia and Neighboring Countries. [In Armenian.] Paris: Palents Publishing House.

Biscione, Raffaele, Simon Hmayakyan, and Neda Parmegiani (editors). 2002. The North-Eastern Frontier: Urartians and Non-Urartians in the Sevan Lake Basin. Rome: CNR, Istituto di studi sulle civilta dell’egeo e del vicino oriente.

Government of the Republic of Armenia. 2002. The Decision of the RA Government on Reorganizing the “Sevan National Park” State Institution, Approving the Statutes of “Sevan” National Park and “Sevan National Park” State Non-Commercial Organization, no. 927-N. [In Armenian.] Yerevan: Government of the Republic of Armenia.

Grigoryan, Avetis. 2020. Memoirs of Medieval Armenian Historians on Historical Sotk. [In Armenian.] HistoricalPhilological Journal 2:186–206.

Hakobyan, Tadevos, Stepan Melik-Bakhshyan, and Hovhannes Barseghyan. 1986. Dictionary of Toponyms of Armenia and Adjacent Regions, Vol. 1. [In Armenian.] Yerevan: Yerevan University Press.

Harutyunyan, Arsen. 2019. The Epigraphic Inscriptions on Dragon-Stones Turned into Cross-Stones. In Vishap between Fairy Tale and Reality. [In Armenian.] Edited by A. Bobokhyan, A. Gilibert, and P. Hnila, pp. 505–17. Yerevan: Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, National Academy of Sciences.

Harutyunyan, Khachik. 2019. Memoirs of Armenian Manuscripts. [In Armenian]. Yerevan: Matenadaran.

Hnila, Pavol, Alessandra Gilibert, and Arsen Bobokhyan. 2019. Prehistoric Sacred Landscapes in the High Mountains: The Case of the Vishap Stelae between Taurus and Kaukasus. In BYZAS 24: Natur und Kult in Anatolien, edited by B. Engels, S. Huy, and C. Steitler, pp. 283–302. Istanbul: Veröffentlichungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Istanbul.

Hovhannisyan, Karen. 2019. Manifestation of the Archetypal Image of Dragon in the Armenian Worldview. In Vishap between Fairy Tale and Reality. [In Armenian.] Edited by A. Bobokhyan, A. Gilibert, and P. Hnila, pp. 75–107. Yerevan: Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, National Academy of Sciences

Korkotyan, Zaven. 1932. The Population of Soviet Armenia during the Last Century (1831–1931). [In Armenian.]

Yerevan: State Publishing House.

Lalayan, Yervand. 1910. New-Bayazet Province or Gegharkunik: Topography, Rural Society of Mazra. [In Armenian.] Ethnographic Journal 19(1):21–30.

Melikset-Bekov, Levon. 1938. Megalithic Culture of Georgia. [In Georgian.] Tbilisi: Federation.

Muradyan, Paruyr. 1985. Turned into Xačk’ar Vishap Stelae from Eghegnadsor. In Artistic Monuments and Problems of Culture of the East. [In Russian.] Edited by B. Lukonin, pp. 20–26. Leningrad: Nauka.

Orbelean, Stepannos. 1910. History of Sisakan Province. [In Armenian.] Tbilisi: N. Aghanean Press.

Petrosyan, Armen. 1987. Reflection of Indo-European Root *wel- in Armenian Mythology. [In Russian.] Herald of Social Sciences 1:56–70.

———. 2015. Thirty Years Later: Vishap Stone Stelae and the Myth of Dragon Slayer. In Vishap Stone Stelae. [In Armenian.] Edited by A. Petrosyan and A. Bobokhyan, pp. 13–52. Yerevan: Science.

Petrosyan, Hamlet. 2008. Khackar: The Origins, Functions, Iconography, Semantics. [In Armenian.] Yerevan: Printinfo.

———. 2015. Some Remarks on Vishap Stelae. In Vishap Stone Stelae. [In Armenian.] Edited by A. Petrosyan and A. Bobokhyan, pp. 81–98. Yerevan: Science.

Rostomov, Ivan. 1898. Akhalkalak District in Archaeological Terms, Collection of Materials on the Description of Localities and Tribes of the Caucasus. [In Russian.] Tbilisi: Directorate of the Caucasus Educational District Press.

Shahinyan, Abraham. 1984. Medieval Monumental Stelae in Armenia: Xačk’ars of the 9th–13th Centuries. [In Armenian.] Yerevan: National Academy of Sciences.

Simonyan, Lilit, and Karen Hovhannisyan. 2019. Ancient Water Supply Systems, Minor Mher and Vishap-Stones. In Vishap between Fairy Tale and Reality [In Armenian.] Edited by A. Bobokhyan, A. Gilibert, and P. Hnila, pp. 164–79. Yerevan: Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, National Academy of Sciences.

Smbateants, Mesrop. 1895. Topography of See-Surrounded Province of Gegharkunik, Which Is Now Nor-Bayazet Province. [In Armenian.] Vagharshapat: Publishing House of the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin).

Yeghiazaryan, Hovsep. 1942. Report of H. Yeghiazaryan, the Collaborator of the Committee for the Preservation of Monuments in Armenia of the Armenian Branch of the USSR Academy of Sciences on the Results of Archaeological Survey in Nor-Bayazet, Martuni and Basargechar Regions. [In Armenian.] National Archives of Armenia, Collection 1063, List 1, Folder 1421, p. 5.

Bikol, the Philippines

conversation

Sur. A barangay is the smallest political unit in the Philippines. Community-engaged work allowed us to interview community leaders and local residents about American industries in the present-day towns of Tinambac and Siruma. Many older community members recall the presence of logging companies during their childhoods and recount stories told by parents and grandparents. Given the important role of priests in the region, our research was greatly facilitated by collaboration with the Archdiocese of Caceres. Detailed drone imagery of barangays, three-dimensional models of selected buildings, and aerial photographs were all important results, which we shared with community members and local governments. Left to right: Maddie Yakal, anthropology graduate student anthropology at UCLA and codirector of this year’s field season, Robin Meyer-Lorey, Stephen Acabado, and Annie Cabral.

St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands

Justin Dunnavant1

Justin Dunnavant1

We returned to Estate Little Princess for the first time since the pandemic to continue archaeological excavations at the eighteenthcentury Danish sugar plantation. Our team comprised colleagues from UC Berkeley, Stanford University, and the California Academy of Sciences, as well as four students in the UC-HBCU program, which seeks to improve diversity and strengthen UC graduate programs by investing in relationships between UC faculty and historically Black colleges and universities. Among the students was Darartu Mulugeta, an undergraduate Bunche Fellow at UCLA. Excavations explored the extent of the village once housing the enslaved community and the architecture of the cabins, as well as the daily life of enslaved Africans on the plantation.

Underwater Archaeology Near Maui and Lana‘i

In October 2022, I received a grant from the National Geographic Society to join a team of maritime archaeologists, educators, and science communicators researching submerged heritage sites around the islands of Maui and Lanai in Hawai‘i. For two weeks, I helped create photogrammetric models of a sunken Grumman F6F Hellcat fighter aircraft, a Curtiss SB2C Helldiver bomber, a tracked amphibious vehicle, and other remains dating to the Second World War. Our

research was complemented by a primary school curriculum created by Ashleigh Glickley. We conducted project operations from the EV Nautilus , owned and operated by Robert Ballard, National Geographic explorer at large, who previously discovered the wrecks of the Titanic (1985), the battleship Bismarck (1989), the USS Yorktown aircraft carrier (1998), and John F. Kennedy’s patrol torpedo boat PT-109 (2002).

Industria (Monteu da Po), Italy

Aresearch project at the Roman city of Industria (modern Monteu da Po), postponed for several years because of the Covid-19 pandemic—which hit northern Italy particularly hard—was at last initiated in September 2022.3 Industria was founded during the first century CE as a typical Roman city to replace the Ligurian settlement of Bodincomagus (mentioned by Pliny the Elder, Natural History iii, 122), its location most likely chosen because of its proximity to the confluence of the Dora Baltea, coming down through the Aosta Valley, and the river Po. Around the same time, and only about 30 km (20 miles) to the west, the Roman city of Augusta Taurinorum (modern Turin) was founded to replace the Ligurian settlement of Taurasia, near the confluence of the river Po and the Dora Riparia, coming down through the Susa Valley.

Under patronage of the Avillius family, the city flourished during the first and second centuries as an industrial town, as reflected in its new name, processing metal ores brought down from the Alps. Originally from Padua, near Venice, the Avillius family had made a fortune in trade across the Aegean Sea, with their main base at the Cycladic island of Delos, and looked to diversify their assets. Initially attracted by possible gold deposits in the Alps, they ultimately settled on exploring the much larger copper deposits and on the production of bronze ingots and

At the time of the founding of Industria, the Roman Empire was at the height of its expansion and power, resulting in an increased exposure to foreign cultures and religions. This was certainly the case for the internationally connected Avillius family. Prominent examples in

Industria was founded during the first century CE

Rome of the resulting fascination with cultures farther east include the pyramid (tomb) of Gaius Cestius (circa 18–12 BCE), statuary of Hadrian and his companion Antinous in remarkable Egyptianized style (circa 135 CE; originally in Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli and now mostly in Room III of the Gregorian Egyptian Museum in the Vatican Museums), eight Egyptian obelisks moved to Rome between around 10 and 350 CE, five obelisks carved in Italy in Egyptian style between around 25 and 275 CE, and the first century CE Bembine Tablet of Isis (Mensa Isaica), now in Museo Egizio in Turin. In Industria, this trend and the influence of the Avillius family seem to have resulted in the two main temples of the city being dedicated to the Egyptian deities Isis and Serapis

After reaching its peak in the second and third centuries CE, the fortune of Industria changed when the river Po slowly moved away from the settlement and Roman economic structures changed. During the fourth century CE, the bronze industry came to an end, and the inhabitants abandoned the city, with many moving into the foothills of the Monferrato Mountains farther south. Most of the Roman building materials were removed to be used elsewhere, and the remains of the city slowly disappeared under orchards and agricultural fields.

During the fourth century the bronze industry endedFigure 4. Willeke Wendrich (left) discusses research strategies with codirector David Walsh of the University of Newcastle.

In the course of the eighteenth century, the dukes of Savoy, based in nearby Turin, developed an interest in Industria, seeing another opportunity to increase their cultural and intellectual standing and with that their political influence among the noble families of Europe. In 1745 Charles Emmanuel III sent his librarians Giovanni Paolo Ricolvi and Antonio Rivautella to investigate the site. They returned to Turin with many ancient artifacts, which became part of the growing collection of the Savoy family. These are now kept in Museo di Antichità in Turin. In Napoleonic times (1798–1814), the site was purchased, excavated, and studied by Count Bernardino Morra di Lauriano. More excavations, as well as protection and presentation of the ancient remains, were performed between 1981 and 2003, mostly under the direction of Elisa Lanza and Emanuela Zanda of the University of Turin. Federico Barello and Alessandro Quercia of the Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio published additional insights, overviews, and reconstructions (Barello 2012; Zanda 2011).

Much of the archaeological attention on the site focused on the center of the city, with its temples and other public buildings, also because many of the ancient remains are below privately owned land. Large areas thus remain mostly unexcavated and understudied, including living quarters, industrial facilities, and cemeteries. This leaves many details of the economic and technological function of the ancient settlement unclear. This holds true for details about the daily life and religious practices of the common inhabitants of the city. After visiting the site several times with students of the summer teaching program in Museo Egizio and in close cooperation with the local authorities, we developed a project to reinvestigate the site,4 focusing on areas outside the protected center of the ancient city. This obviously required significant communication with the local community to reach consensus on the meaning and value of the ancient remains. The name of the project—Comunità Antiche e Moderne a Industria (Ancient and Modern Communities at Industria)—reflects this focus.