EDITORS’ LETTER by the Editors

Cultural Currency

KLARA AND THE SUN: HAGIOGRAPHY OF AN AI

by Tracey Leary

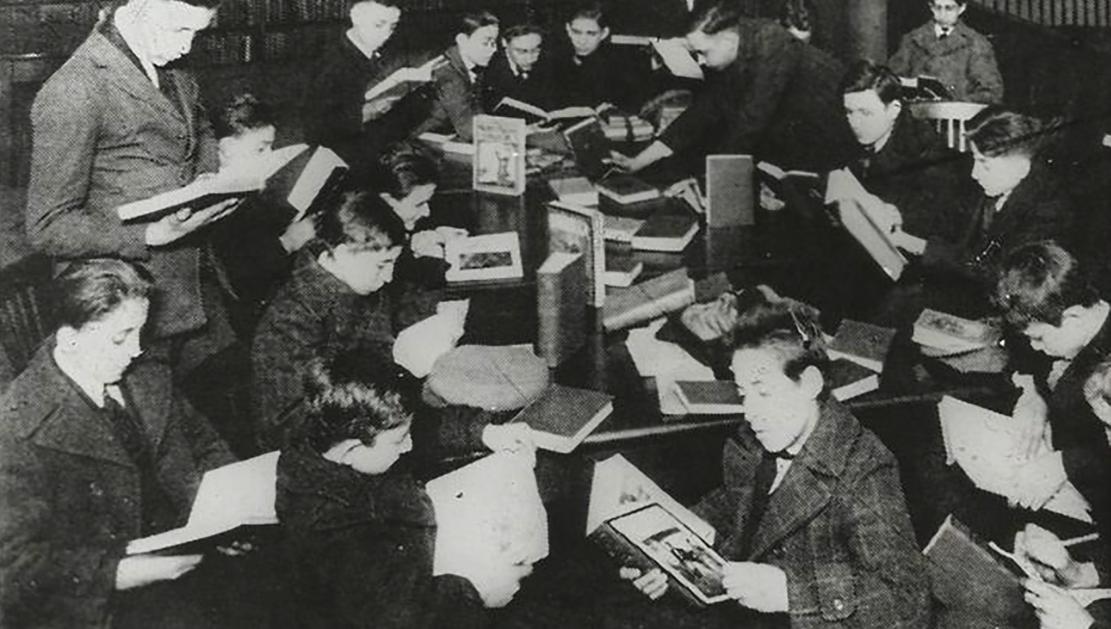

From the Classroom

WHAT I LEARNED TEACHING EIGHTHGRADE BOYS

by Kara Griffith

BOOK REVIEWS

THE WORK OF WRITING HISTORY

by John Wilson

PLATO ’S DIALOGUES AND THE MODERN TEACHER

by Matthew Bianco

A GOOD YEAR FOR DANTE

by Sean Johnson

READING THE ETERNITIES

by Sean Johnson

This magazine is published by the CiRCE Institute. Copyright CiRCE Institute 2022. For additional content, please go to formajournal.com.

For information regarding reproduction, submission, or advertising, please email formamag@circeinstitute.org.

Contact FORMA Journal

81 McCachern Blvd SE - Concord, NC 28025

704.794.2227 - formamag@circeinstitute.org

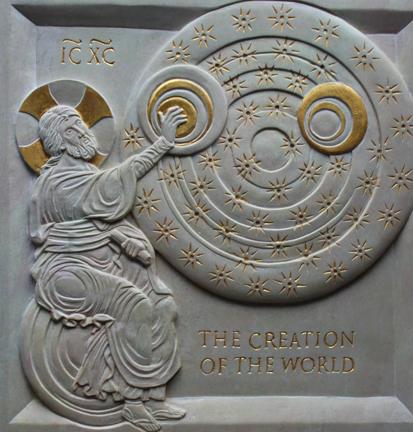

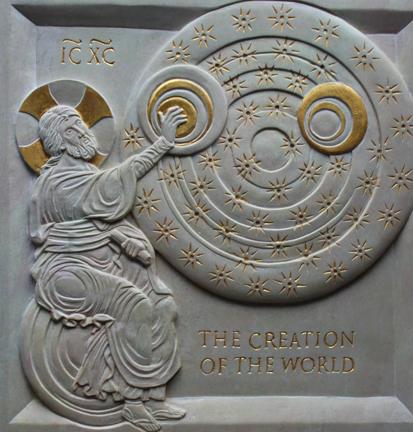

Cover Art: "Creation 2" by Jonathan Pageau

Issue 17

Winter 2022

BRINGING IT ALL BACK HOME: THE ODYSSEY IN TRANSLATION

by Monique Neal

BOOK EXCERPT: THE SCANDAL OF HOLINESS

by Jessica Hooten Wilson

THE GOLDEN ECHO

by Joshua Leland

AN ANCIENT DESCENT IN A MODERN

HELL: “THE UNDERWORLD ” UNDER THE INFLUENCE

by Joshura Hren

WHAT ARE STANZAS FOR?

by James Matthew Wilson

REDISCOVERING THE GOLDEN KEY A Conversation with Jonathan Pageau by Katerina Kern

The CiRCE Institute is a non-profit 501(c)3 organization that exists to promote and support classical education in the school and in the home. We seek to identify the ancient principles of learning, to communicate them enthusiastically, and to apply them vigorously in today’s educational settings through curricula development, teacher training, events, an online academy, and a content-laden website. Learn more at circeinstitute.com

COLUMNS FEATURES

6

28

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER 22 66 8 76 32 POETRY 11 40 17 36 MARY ROMERO 13

INTERVIEW

48 15 60 JAMES MATTHEW WILSON

Editors' Letter

Dear Readers,

Welcome

to a new edition of FORMA, where we steadfastly believe the great works of the past speak universal truths that we cannot afford to ignore.

In this issue, we’ve asked our authors to explore the theme of mythos, and you now hold the outcome of that project. Because we intended this to be a free exploration, we did not define mythos in the call for papers. But we will offer you, the reader, some context for the term, and you can determine how well it plays out in the submissions.

Mythos can be understood narrowly as a collection of myths or stories told by a given people at a given time to interpret natural phenomena or explain the origins of life. These stories personify potent forces in human experience: weather, emotions, virtues and vices, time, etc. They are the stories humans have told to explain reality and teach children how to live according to it. But mythos can transcend the genre of “myth,” for stories always interpret reality and we are always telling stories. We live and breathe inside stories. Some might even say we are stories. So mythos can refer to the patterns and structures we use to speak of, and live within, reality.

This perspective unapologetically assumes that reality is patterned and ordered rather than chaotic and random; the hero dies and resurrects, not because we repeat the same story continually, but because the pattern of death and resurrection is true and embeds itself within our cosmos, and we embed it, in turn, within our stories. The patterns came first, and we echo those patterns.

We intentionally chose not to define mythos in our call for papers for this edition, wanting to allow the multivalence of the term to appear in the variety of the works that you find here. Some of the pieces directly relate to mythos, while others do so more implicitly. We leave it to you to consider how mythos informs each piece.

Cheers,

The Editors

The Editorial Team

Publisher: Andrew Kern, President of The CiRCE Institute

Editor-in-Chief: David Kern

Managing Editor: Katerina Kern

Art Director: Graeme Pitman

Poetry Editor: Christine Perrin

Contributing Editor: Noah Perrin

Copy Editor: Emily Callihan

“Mythological thinking cannot be superseded, because it forms the framework and context for all thinking.”

Northrop Frye

KLARA AND THE SUN: HAGIOGRAPHY OF AN AI

Kazuo Ishiguro’s latest book, Klara and the Sun, deepens his ongoing exploration of the themes of loyalty and service in a divided community. Remains of the Day, his 1989 Booker Prize–winning novel, followed a butler at the end of his years of usefulness during the decades leading up to World War II, a time in which the loyalties of the British people had fractured over their response to the rising Nazi regime in Germany. Klara and the Sun contemplates similar issues, but this time in a dystopian setting, appearing at first glance little different from modern life—apart from the active involvement of artificial intelligence in the lives of humans, which takes the form of “AFs” or “Artificial Friends.” The titular character is one such AF, and is for sale to any parent wealthy enough to purchase her companionship for their child. Early in the novel, Klara finds a home with a young teen named Josie, and it is in her new environment that the second glaring difference from our world becomes apparent, for Klara learns that Josie is a “lifted” child.

By Tracey Leary

Ishiguro never fully explains “lifting,” but it appears to be a type of voluntary genetic editing that takes place after a child is born. Lifted children are supposed to have superior intellectual capabilities to those who have not been lifted. They are eligible to attend most universities, many of which no longer accept unlifted students, and can expect greater economic prosperity after graduation. However, lifting comes with a price beyond the monetary— lifted children also have much greater potential for serious health issues directly related to this process. In the world of the book, both lifted and unlifted children are isolated and lonely, spending their days with virtual tutors and interacting little with other people their age except for sparsely scheduled gatherings to hone their social skills, sessions to which unlifted children are rarely invited. Klara enters Josie’s world to alleviate some of the loneliness that naturally coincides with being lifted. Yet by the end of the novel, she has transcended her role as an AF in ways that strongly suggest that we are meant to read Klara as a saint, ways that call to mind the me-

8 | WINTER 2022 / FORMA

Cultural Currency

dieval motifs of traditional hagiography.

From the first pages of the novel, it is evident that Klara surpasses her programming as an AF in a very unusual way: she worships. Klara runs on solar power, and because of this, she believes that the sun is the source of life not only for AFs but for humans as well. While waiting to be purchased in the AF store, she watches a homeless man, whom she calls “Beggar Man,” appear to die on a cloudy day. He lies motionless on the sidewalk beside his dog, unnoticed by the many pedestrians that hurry past. When the sun comes out in all its brilliance the next day, Beggar Man and his dog have revived, and Klara believes that “a special kind of nourishment from the Sun had saved them.” When Klara comes to live in Josie’s home, Josie quickly realizes that Klara loves watching the sun set behind a nearby barn, so they make a ritual of this time, kneeling on Josie’s “Button Couch,” as a votary kneels at an altar, while the sun “goes to his resting place.”

When Josie’s health takes a turn for the worse, Klara determines to make a pilgrimage to this barn—a difficult journey for an AF unaccustomed to walking on uneven terrain. She is helped by Josie’s one friend and neighbor, Rick, who carries her to the barn where Klara pleads with the Sun to heal Josie as he did Beggar Man. Believing the Sun wants her to perform an act of devotion to prove her worthiness to make this request, she decides that she must battle in some way with a force of darkness, a force which is necessarily opposed to the sun. The darkest force that Klara can imagine is a machine that was set up outside the AF store during her time there that polluted the atmosphere with thick smoke, obscuring the sun when it ran. Klara believes that this machine offends the sun and that she must destroy it in order to prove her devotion to the Sun and to obtain her plea. Visiting the city, Klara has the opportunity to disable this machine, but must sacrifice part of herself to do so. She also learns that Josie’s family has an additional purpose for her, one which requires her to study Josie so intently that she can represent her in every conceivable way. This discovery leads to one of the central questions Ishiguro addresses in this novel: Can Klara truly know Josie’s soul? Klara believes that she can. She describes her study of Josie as walking through each room of Josie’s mind, studying each carefully until she knows them all implicitly. Josie’s

father is not sure that this is possible, and questions the belief of his world’s belief that there is nothing unique or unknowable about the human heart.

Unlike Josie’s father, Klara seems to be unaware of the presence and unpredictability of sin in a human soul. Created with only the programming that enables her to function as a child’s companion, Klara in many ways begins her existence with a true tabula rasa. We might call it an immaculate conception. Because Klara has never eaten of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, she cannot recognize evil when she sees it. Klara looks at her world with a purity of vision that enables her to recognize many subtle dynamics in the behavior and motives of those around her, but without a moral understanding of the danger of some of those motives, and the possibility that humans can intend harm to others. Scripture says that the pure in heart shall see God, and it is this purity of vision that fuels the uncanny perception that Klara possesses and which Ishiguro explores throughout the novel. However, Klara’s purity of motive also prevents her from truly understanding her own place in that corrupted world and her destiny at the end of her usefulness to Josie.

As most canonized saints are associated with miraculous activity, Klara does experience an apparent miracle which changes the course of the novel and of her family’s life. And like a true saint, Klara accepts all that comes to her after this miracle without complaining or casting blame, even as her own suffering increases. The novel closes with a definitive statement of Klara’s fidelity to the Sun and his kindness to her.

Interestingly, the canonized saint with the name closest to Klara is Saint Clare, who founded the order known as the Poor Clares, to work with St. Francis’, brotherhood of Franciscans. St. Clare, because of her miraculous ability to view the mass on the wall of her cell when she was physically unable to attend services, is now the patron saint of televisions and computers. The similarity between the names cannot be a coincidence. Ishiguro has given us his vision of a modern-day saint, and it is a convincing and thought-provoking one.

Tracey Leary teaches online courses in the integrated humanities with Kepler Education. She lives in Alabama with her husband, three boys, and a guinea pig.

FORMA / WINTER 2022 | 9 Cultural Currency

THE WORK OF WRITING HISTORY

By John Wilson

Fiction, memoir, biography, history, essay-collections, reportage, science, philosophy, theology, writing that takes off from movies and music and art and more: which branch is most inadequately assessed in our public book-talk, in reviews and podcasts, on Twitter and elsewhere? I would say history, hands down. But what do you get when you read a typical review of a work of history? Mostly a summary of the subject at hand. Insofar as there is any account of the writing, it is likely to be limited to a few stock responses, pro or con (the historian is “biased,” leaning too obviously “left” or “right”; the historian is dumbing his subject down or writing only for fellow-mandarins, but—let there be trumpets and zithers—now and then she is wonderfully “readable,” etc., etc.). What we rarely get is any acknowledgment that writing history requires imagination every bit as much as it requires research. It is not an assemblage of “facts.”

This came to mind as I was reading an advance copy of Barry Strauss’ splendid new book The War

That Made the Roman Empire: Antony, Cleopatra, and Octavian at Actium, coming in March from Simon & Schuster. Strauss is one of my favorite historians, and this may be his best book in a distinguished career. Those who have a particular passion for the classical world (or simply a fascination with Antony and Cleopatra), not to mention connoisseurs of great naval battles, should already have this book on their wish list, but Strauss is writing for a broad audience.

Consider this brief passage from Strauss’ prologue, in which (at the very outset of his book) he describes the once-famous monument created by the victorious Octavian (soon to become Augustus Caesar) around 29 BC, two years after the Battle of Actium—a monument that until recently had long been obscured. “At Nicopolis,” Strauss observes, Octavian wrote the history of his triumph “in stone.” But then, Strauss adds, “he also wrote it in ink, in Memoirs that were famous in antiquity” but that vanished “long ago”; only fugitive fragments survived.

This is an incidental detail, and yet it will give the attentive reader a jolt. How did that happen? The Memoirs of the great Augustus Caesar were simply lost? In conjunction with the more developed account of the monument at Nicopolis, obscured for

FORMA / WINTER 2022 | 11

Book Review

centuries, this nudges us to step back from our own moment, to recognize that much we take for granted will also be erased in the vicissitudes of time.

Strauss’ book is loaded with moments like this, along with his persuasive argument for the historical consequences of Octavian’s victory (“If Antony and Cleopatra had won, the center of gravity of the Roman Empire would have shifted eastward”), the immersive details of battle between the contending forces (including a crucial contest some months before the massive sea-battle at Actium), intense personal passions, and intricate behind-the-scenes maneuvering on both sides, including a good deal of old-fashioned espionage.

To keep all these lines of the narrative in play, now foregrounding one, now highlighting another, holding the reader’s attention with no sense of disorientation, requires skills akin to but not identical with those of a gifted novelist. This crucial aspect of history-writing—whether it be superbly managed, as here, or shoddily handled, as is sometimes the case—routinely gets short shrift in reviews. Be sure to savor the art and the craft as you read.

The official pub date for The War That Made the Roman Empire is March 15. That same day is the pub date for Peter Handke’s Quiet Places (FSG), a collection of essays, two of which have not previously appeared in English. (Also on March 15, FSG will publish a translation of Handke’s novel The Fruit Thief, which appeared in German in 2017.) Even if you haven’t read Handke, you may remember the controversy (if that’s the right word) in October 2019 following the announcement that he had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. Handke, critics charged, was an apologist for genocide perpetrated by Serbs against Bosnian Muslims. One writer, the former editor of the books section of a major U.S. newspaper, bragged that she had never read Handke and didn’t intend to start doing so now.

In response, I wrote a column for First Things

in Handke’s defense called “Why You Should Read Peter Handke.” At that point, I expected that most of the leading bookish magazines and journals would be assigning retrospective accounts of his long career in the wake of the prize and the ensuing invective. Stunningly, very few such pieces appeared. In March, with the publication of The Fruit Thief and Quiet Places, it will be hard to further evade that responsibility.

When I tell you that the long title essay of Quiet Places (written in 2011) begins with Handke’s memories of outhouses, boarding-school and railroad-station toilets, restrooms (especially in Japan), and so on, you may be inclined to pass. That’s fine. Despite the title assigned to my First Things column on Handke, I have no interest in pushing his books on you. But if you read the essay, in which the notion of Quiet Places is extended imaginatively well beyond its starting point, you will find that it is an extraordinary expression of one writer’s sensibility, of the distinctive way he experiences the world—“autobiographical” in the deepest sense, even as it eludes the customary strategies of “memoir.” If you dislike this essay, you are very unlikely to enjoy Handke’s fiction. If on the other hand you find it irresistible, you have a lot of good reading to look forward to.

John Wilson edited Books & Culture (1995–2016). He writes regularly for First Things and a range of other magazines. He is a contributing editor at the Englewood Review of Books and senior editor at Marginalia Review of Books

12 | WINTER 2022 / FORMA Book Review

PLATO'S DIALOGUES AND THE MODERN TEACHER

By Matthew Bianco

Plato’s famous protagonist and history’s most famous philosopher, Socrates, has served as the ideal type of teacher for millennia, showing teachers how and why to engage their students in dialogue. Yet, in committing to Socratic teaching, the teacher attempts to imitate the inimitable—to be what only one has been before. Still, we strive, longing to one day ask questions so profound and necessary they propel our students into direct encounter with Truth. And for that, we will read books and gather wisdom and attend lectures. As we seek the tools of Truth perception and how to teach them, Jeffrey S. Lehman offers his insight and participation in this worthy quest.

Many in the tradition, philosophical and classical, see Socrates as a philosopher, the gadfly of Athens, and the mouthpiece of Plato. Those with this view believe that, if one wants to understand Plato’s beliefs, one must read what Socrates says; Socrates’ words are the words of Plato. This is not the belief of all in the tradition, perhaps not even

the majority. For some, Plato expressed his philosophy through Socrates, other characters, the form of the text, and the dramatic or literary elements of the dialogue. Those who read Plato in this light read his dialogues less as a philosophical treatise and more as an embodied philosophical mode. In other words, Plato’s dialogues seek to teach how he does philosophy more than what his philosophy is. The content of his philosophy is, of course, contained in the dialogues, but readers should attend more to the mode than the content.

In this sense, then, the dialogues beg the Socratic teacher to see Socrates not as the ideal philosopher but as the ideal teacher. If one were to read the dialogues dramatically, as if Plato had written plays, then we may meet Socrates anew, learning not the belief of Plato but a manner of inquiry.

This is precisely what Lehman’s new book, Socratic Conversation: Bringing the Dialogues of Plato and the Socratic Tradition into Today’s Classroom, has done. In it, he walks the reader through a few of Plato’s dialogues in order to demonstrate and derive principles that may guide classroom conversation. Then he does the same thing with subsequent dialogues within the Christian tradition, deriving additional principles of conversation. Finally, he applies these derived principles in the classroom. These principles include philosophical friendship, verbal psychagogy, the compatibility of mythos and

FORMA / WINTER 2022 | 13 Book Review

logos, an opposition to misology, the role of the “Inner Teacher,” the enchantment of Socratic conversation, and the political role of Socratic conversation.

Lehman uses the Meno to illustrate philosophical friendship. He notes that the teacher guides Socratic conversation by encouraging a spirit of friendship as the students engage in philosophical conversation. This friendship, he asserts, is key to a genuine pursuit of truth in dialogue.

With the Phaedrus, he illustrates “verbal psychagogy”: the “leading of the soul,” as Plato puts it. Verbal psychagogy is neither persuasion nor the assertion of a “right” answer, but the use of questions to invite the students into the philosophical life.

In the Phaedo, Lehman illustrates the compatibility of mythos and logos. He notes that people often think of mythos (storytelling) as a means of resuscitating a failed Socratic conversation; if the student fails to see truth, the guide falls back on mythos, leaving the student something to contemplate. Lehman argues mythos and logos are better understood as means of “appealing to different elements within the soul” (81). This understanding highlights the value of both modes of presentation, granting the Socratic guide permission to use both as needed.

Lehman then notes the principle of “opposing misology” in the Phaedo and the Republic. Misology is the hatred of argument and discussion and, ultimately, logic and reason—an argument he develops from Socrates’ comments in the Phaedo and from D.C. Schindler’s work Plato’s Critique of Impure Reason: On Goodness and Truth. When viewed together, these Platonic dialogues provide the principles for classical education and the Socratic conversation, enabling the cultivation of love for both reason and one’s fellow learners.

Lehman then turns to later Christian examples of the Socratic conversation: Augustine, Boethius, and Thomas More. In these he notes the importance of the “inner teacher”—or divine revelation—the enchantment of the dialogue with wisdom, and the political role of the Socratic conversation, respectively.

To get “practical,” as some might say, Lehman offers helpful advice for leading the discussion in the classical classroom. First, he encourages the guide to embody and encourage active, attentive listening. This may seem obvious, but you might be surprised

to find how quickly a Socratic conversation can devolve into parallel monologues.

His next rule is to ensure that the Socratic conversation stays on topic. Again, this seems obvious, but it is much more difficult to do if it is not intentionally protected. Many students easily get off topic by blurting out a newer, “better” question, or by telling personal stories (that they think are connected to the original topic but are not necessarily) that lead the conversation astray.

Next, avoid serial monologues. It is not just the parallel monologue that prevents real Socratic conversation, but even serial monologues, where no one is asking or thinking about a question or how others have contributed to it, but simply taking turns describing their own opinions without connecting them.

Always refer to the text or work. This rule can be the most effective at staying on topic and preventing monologues because the students have to make their case from the text itself. They cannot use extraneous sources (unless the teacher allows, but even then it should be directly and explicitly connected back to the text) or personal experiences, thus preventing or at least mitigating monologues and off-topic conversations.

Lastly, remember your manners. Don’t be rude. Assume that every person there has something valuable, something that can draw out a new idea about the subject for everyone.

Lehman’s book is a welcome and helpful contribution to the classical teacher’s toolkit. Classical school teachers often feel unprepared to lead Socratic conversations, especially new teachers. Yet, as Lehman argues, the Socratic conversation is one of the most classical and fitting modes of teaching. Thus, the contribution he makes in this book to help teachers do what seems difficult, and to translate what they encounter when reading a Platonic dialogue into a classroom experience, is invaluable at this stage in the classical renewal. This is a welcome book. It should be read by anyone who takes Socratic teaching seriously.

14 | WINTER 2022 / FORMA FORMA / WINTER 2020 14 Book Review

Dr. Matthew Bianco is the Chief Operating Officer of The CiRCE Institute and Head Mentor for CiRCE’s teacher training apprenticeship program, where he trains teachers in using the Socratic method.

A GOOD YEAR FOR DANTE

By Sean Johnson

The two thousand and twenty-first year of our Lord may have over-promised and under-delivered on a tragic number of fronts, but for lovers of Dante the seven hundredth anniversary of the poet’s death will go down as a good vintage. His works have received a swell of attention—critical as well as popular—through efforts like 100 Days of Dante, a national reading group and lecture series presented by Baylor Honors College and several other partner schools, and a slew of new books.

The year’s notable publications include two critical works and a new translation. Veteran scholar John Took’s study, Why Dante Matters, finds Dante’s enduring value in the dialectic (or give-and-take dialogue) he creates between philosophy and poetry. The fruit of that union, something both more and less than theology, is expressed in the plain language of the poet’s own people but still manages to find fresh and relevant expression in every age. Took looks at Dante’s poems partially from a psychological standpoint, and ascribes this success, in part, to Dante’s skill for dramatizing complex mental movements in clear poetic imagery.

The other critical study is Love’s Scribe, by poet

and gifted Dante translator Andrew Frisardi. Frisardi turns a close-reading eye on the richly layered symbolism of Dante’s poems. He finds in the poet’s intricate and subtle uses of biblical literature cause for renewed insistence that Dante’s Christian “orthodoxy is indispensable to his poetic [way of knowing],” but he also breaks new ground on the significance of the Orpheus myth in The Divine Comedy

The work of both scholars is married serendipitously in David M. Black’s new translation of Purgatorio for NYRB. Black is both poet and psychoanalyst by trade, and cites the influence of both Took and Frisardi in his introduction. He combines insight into the workings of the mind with a poet’s ear and eye for imagery, to render an English Purgatory remarkably true to Dante’s original vision. He favors a plain diction, and his unrhymed verse has an unscrupulous meter that frequently varies, but at no point does Dante’s verse feel underserved. After all, Dante himself made the unprecedented choice of writing his Comedy in an Italian vernacular so its language would be closer to the common experience of his audience. The grandeur of his verse is undeniable, but it came as much through his ordering of words and the images he constructed with them as from the words themselves.

A language is more than a collection of symbols and translation, at its best, is more than the decoding and encoding of ideas. A language is a mode of

FORMA / WINTER 2022 | 15

Book Review

thinking and a world unto itself. Word for word, one of the greatest achievements in English literature is the utterance “lippity-lippity.” Beatrix Potter capturing the absolute essence of bunnies in the simple repetition of a nonsense word demonstrates the very pinnacle of the vernacular, and the impossibility of translating “lippity-lippity” reveals the difficulty facing anyone attempting to lift poetic feelings and images from one language and plunk them down in another.

Most of Dante’s notable translators have approached the project as a balancing of poetry and meaning. Dante’s unique and intricate terza rima is almost impossible to render into English without prioritizing some elements over others, and not a few translations stand or fall on the elements they choose. Dorothy Sayers, unarguably a translational genius, nonetheless overplays her hand by committing slavishly to a rigid rhyme scheme that clunks as often as it sings.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, unimpeded by end-rhymes, crafted the most exquisite and transporting verse rendering of the Comedy that English has seen or may ever see, but even his language, when it soars, can obscure the finer points of Dante’s intricate descriptions. Consider this account of the way the senses direct the soul toward the objects of its loves:

Your apprehension from some real thing

An image draws, and in yourselves displays it So that it makes the soul turn into it.

And if, when turned, towards it she may incline, Love is that inclination; it is nature Which is by pleasure bound in you anew

Compare, then, Black’s version of the same passage:

Your apprehension from some actual thing Takes what’s called an “intention” and unpacks it within you so that the mind can turn toward it; and if the mind, once turned, incline toward it, that inclination is love: all this is nature, that’s bound in you by pleasure from the outset.

Certain features of Dante’s original lines are visible underneath both versions, but Black has arguably rendered the complexity more simply. His contracted “what’s” offends a little, but rhymes (if you will) nicely with the frank tone, and the intangible, inward process being described comes through with workmanlike clarity.

Black’s lines rarely soar, but they can draw deep waters out of the heart of man—“Less than a single dram / of blood remains in me that is not trembling! / I sense the presence of the ancient fire!” And in helping English readers draw nearer to the inward sense of Dante’s intimidating masterwork he has more than redeemed the year.

Book Review

READING THE ETERNITIES

By Sean Johnson

By Sean Johnson

The news” was already a problem when Leo Tolstoy began writing Anna Karenina in the 1870s. Although it would be another two decades before the term “yellow journalism” was coined, and almost three before William Randolph Hurst told a photojournalist, “You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war,” Tolstoy could read the writing on the wall. But he could also see past the threat of “fake news” to a deeper danger that would alter our very capacity to understand the world rightly.

He was so wary of printed “news” that he characterized the shallow and faithless Stepan Oblonsky, in part, through the description of his news consumption. On the heels of detailing Oblonsky’s lack of contrition over recent adultery, Tolstoy tells us about the paper he read every morning:

not an extreme Liberal paper but one that expressed the opinions of the majority. And although neither science, art, nor politics specially interested him, he firmly held the opinions of the majority and of his paper on those subjects, changing his views when the major-

ity changed theirs—or rather, not changing them—they changed imperceptibly of their own accord.

Oblonsky “was obliged to hold views,” and appreciated his paper because it saved him the trouble of forming them himself—“he loved his paper as he loved his after-dinner cigar, for the slight mistiness it produced in his brain.”

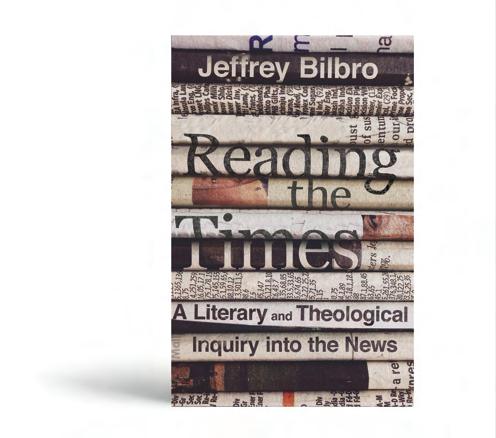

The sobering suggestion at the heart of Jeffrey Bilbro’s recent book, Reading the Times: A Literary and Theological Inquiry into the News, is that we are all becoming Stepan Oblonsky. Complaints about the news are nothing new, and in recent years it has become commonplace even for journalists to turn on one another and for prominent publications to tack bathetic slogans onto their mastheads advertising themselves as the purveyors of “true” news. Though Bilbro creates a few pesky ambiguities by never offering a strict definition of “news,” there is no mistaking his subject, and his meaning remains aspic-clear. He contends that hand-wringing over the reliability of news outlets is something of a red herring, and that a better remedy for our trouble with “the news” is careful reevaluation of the role we grant it in our lives. True, “fake,” or otherwise, the issue is not what’s in our news, but what our news is doing to us.

Bilbro comments, in turn, on a series of sages who help him name the deleterious effects of mod-

FORMA / WINTER 2022 | 17 17 | AUTUMN 2018 / FORMA Book Review

ern news and provide models for living beyond them. The first and chief is writer-activist Henry David Thoreau, who pointed to the modern industrialization of the news as both its defining feature and the cause of greatest harm to its readers. The ability to produce and distribute a new abundance of news content was soon followed by the need to produce a new abundance of news content. Steam-powered improvements to printing technology and transportation turned news into The News, a commodity whose value was reckoned in tonnage. Bilbro relates Thoreau’s observation that “the increased abundance and speed of the news threaten to fragment our attention and damage our ability to see what is really happening and to think rightly about these events.”

Thoreau made vivid the fragmenting of our attention through the metaphor of macadamization, a method of paving roads with millions of small, broken stones. To remain profitable, the news must come rapidly and concern itself with people and events far outside of our natural sphere of experience, so that a mind that dines routinely on news becomes macadamized—divided between a thousand matters in a thousand places without the context to weigh the value of one against the others. Thoreau warns with dumbfounding prescience of the mind’s ability to be “permanently profaned by the habit of attending to profane things . . . its foundation broken into fragments for the wheels of travel to roll over.” In our day, as in Thoreau’s, the problem is not a shortage of reliable voices but the sheer number and volume of voices—the more attention we give them, the less we are capable of attending deeply to anything at all.

Thoreau’s solution, built on one of the most serious puns in history, is to “Read not the Times. Read the Eternities. Knowledge does not come to us by details, but by flashes of light from heaven.” Bilbro assures readers this is far from a mystical escapism, but the strategy of many of the modern era’s greatest activists. Here he borrows the ancient Greek distinction of chronos time and kairos time. A constant flow of news confines our existence within the mundane, wasting, minute-to-minute, factory-whistle world of chronos time, and increasingly bars our entry into the larger, transcendent cycles of kairos time—a heavenly time or timelessness.

Beside Thoreau, Bilbro introduces a series of oth-

er exemplars—Thomas Merton, Simone Weil, Blaise Pascal, and others—who managed to decentralize their own experience with the news. Each in their own way cut out the vague and disconnected middle distance where mass-produced “news” originates, instead focusing on both the transcendent realities beyond this life and the immediate concerns of their neighbors. Their detachment from the “daily scrum” of current affairs actually augmented their momentous contributions to the political and social causes of their own times and places. He shows how each highlighted figure gives the lie to that crass old charge of being “so heavenly-minded they are no earthly good.” Their lives rather prove C.S. Lewis’ observation: “If you read history you will find that the Christians who did most for the present world were just those who thought most of the next.” Bilbro shows us how each found a way to speak out of the firm kairos harmonies of existence into the harried, chronos-bound troubles of their fellow man.

German philosopher Georg W.F. Hegel mocked such a posture when he endorsed reading the morning paper as “the realist’s morning prayer.” He contended that one may orient one’s “attitude toward the world either by God or by what the world is” and that both options are equally valid. He misses the hidden insight in Lewis’ comment above that only God and the things of God can make us much use to our neighbor. Hegel’s materialists may often elect to be selfless or magnanimous, but there is nothing stronger than their own preference keeping them so.

Oblonsky is one. Even as his wife is shut in her room, weeping over his infidelities, he can placidly take his breakfast and read his paper, content that he is still attending to matters of importance—important because they, no less than his domestic concerns, are real and reflect “what the world is.” When his mind turns momentarily to church, he wonders “why one should use all that dreadfully high-flown language about another world while one can live so merrily in this one.”

Though Tolstoy does not garner a mention in Reading the Times, both he and his characters certainly merit a place among Bilbro’s luminaries. Alongside pitiable, macadamized souls like Oblonsky, Tolstoy imagined their healthier counterparts in figures like Konstantin Levin—Anna Karenina’s true hero. A

18 | WINTER 2022 / FORMA Book Review

mirror for Tolstoy’s own convictions, Levin keeps away from the intrigue of metropolitan life, preferring to raise a family and work beside peasants in the country. But these commitments only amplify his ability to see and speak decisively into his world’s weightier affairs when they arise. He lacks that mistiness of the brain that determines his views for him.

“Don’t get your news from the TV,” Bilbro concludes. “When you watch or listen to or read the news, you are catching a community’s ways of thinking—and feeling—about the events of the day.” If that “community” is a corporation with primarily financial motivations, you won’t be catching anything good. At this point I might’ve liked him to make a plea for the revival of inn- and pub-culture, and the slow gathering of news by word of mouth over frosty, frothy, steaming, or otherwise overflowing mugs of whatever you please. Alack, he is silent on that front, but for many of the spread-out communities of modern cities his suggestions represent the best alternatives.

“Seek out organizations that operate on a longer wavelength—not the moment-by-moment chatter of Twitter but the slower forms of thinking found in monthly or quarterly periodicals or books.” Look, he says, for small journals put out by people in your area, or found one of your own, where the overhead is low and the goal is to inform people of the ideas and good work going on around them, so that they can join in. He admits that a journal, like one of Lewis’ Christians or one of Tolstoy’s rustics, seems an unlikely hero. “A journal is an exceedingly modest affair, after all, born of the hope that human beings, trailing one another from page to page, might just be listening, and listening keenly, to one another.” Upon that possibility he grounds his hopes for many healed souls and many new lifegiving enterprises. May the very fact you are reading these words be some small proof that his hopes are well founded.

Book Review

Sean Johnson teaches medieval literature at Veritas School in Richmond, Virginia.

The following is an excerpt from chapter one of Jessica Hooten Wilson’s forthcoming book, The Scandal of Holiness: Renewing Your Imagination in the Company of Literary Saints. Walking through classic works of literature such as Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop; cult favorites like Kristin Lavransdatter; popular Protestant novels such as C.S. Lewis’ That Hideous Strength; canonically Catholic novels like The Diary of a Country Priest; lesser appreciated works such as Zora Neale Hurston’s Moses, Man of the Mountain; and others, Hooten Wilson draws from our multivalent Christian tradition to see holiness in the diverse array of saints. The characters in these novels replace the false heroes and idols handed to us by our culture and become the holy company we need to answer faithfully the Lord’s call to reform us into saints ourselves.

Inhis account of his time in the concentration camps in World War II, Elie Wiesel witnesses his father’s death. For a week, his father grows weaker and more delusional, unable even to climb out of his bed to relieve himself. The others in the camp beat him and steal his ration of bread. The elder of the block of cells advises the fifteen-year-old Wiesel, “In this place, it is every man for himself, and you cannot think of others. . . . In this place there is no such thing as father, brother, friend. . . . Let me give you some good advice: stop giving your ration of bread and soup to your old father. You cannot help him anymore. . . . In fact, you should be getting his rations.” The young boy listens as one who has experienced the worst kind of suffering—abuse, sickness, starvation, hopelessness. For a split second, he considers hoarding his father’s ration for himself. Even mulling over the possibility leaves him feeling guilty.

Why? Why does Wiesel’s hesitancy in this moment cause him guilt? To take his father’s ration is reasonable: the old man will soon die; he’ll be oblivious to his son’s theft; he may even encourage his son, in his right mind, to take the ration for himself. Not to mention, Wiesel needs the food: his body is starving. This brief moment in Wiesel’s memoir reveals that human beings are more than mere minds or appetites. There is something in us that cannot be con-

tained within the body-mind dichotomy, something else where filial piety, generosity, magnanimity, and guilt are manifest.

Humans with Chests

Only a year before Wiesel’s deportation to Auschwitz, C. S. Lewis—seemingly a world away in England—gave a series of talks about this middle sphere of the human person, which he calls “the chest—the seat of Magnanimity, of emotions organized by trained habit into stable sentiments.” This part of the person is what makes us human beings. It is our heart, the place where morality is felt and willed. According to Lewis, “It may even be said that it is by this middle element that man is man.” Whereas the world allows us only two options—we are either beasts ruled by our guts or we are brains who rule by the power of our intellect—Lewis prioritizes this third part as the true indicator of humanity. He published these talks in 1943 as The Abolition of Man

The book centers on education and culture, seeking to answer the question, How do we cultivate human beings with chests? Not every person in the concentration camps responded to suffer-

20 | WINTER 2022 / FORMA

ing with the character—or chest—of Elie Wiesel. In Night, the young Elie watches one son abandon his father and prays to not be like him. While it may seem like a strange undertaking for Lewis to have written a book about education and culture in the midst of war and the Holocaust, Lewis knew the necessity of such a work. Nazis did not rise up from hell to impose their viciousness on Europe. They were formed by the schools that were controlled by the government, the cowardly withdrawal of many churches, and the misuse of language that encouraged masses of people to swallow evil as though it was a palliative. Lewis explains that the formation of Nazis may begin with something as seemingly benign as a textbook that unwittingly dismantles objective beauty and discards our emotional responses as irrelevant.

As a storyteller, however, Lewis knew that the most compelling work was not a collection of essays on education but a novel (though I highly recommend everyone read The Abolition of Man regularly if you care about a flourishing human culture). Lewis had already published Out of the Silent Planet, the first in his space adventure trilogy. He and J. R. R. Tolkien had agreed to write the kind of stories they themselves enjoyed, what Lewis calls in the dedication of the book a “space-and-time-story.” At the end of that story—a rather crazy romp on planet Mars— the main character, Dr. Ransom, a philologist (who seems to be based on Tolkien), decides to publish his experience as fiction. For one, his story seems unbelievable and would not be heard as fact. Second, fiction has “the incidental advantage of reaching a wider public.” In this decision, we glean from Lewis his desire to proselytize, to ensure that a large audience change after reading his book. By the time Lewis writes the third novel in the series, That Hideous Strength, he informs his reader in the preface that the book is a storied version of The Abolition of Man: “a ‘tall story’ about devilry though it has behind it a serious ‘point.’”

What is that serious point Lewis hopes readers draw from That Hideous Strength?

In The Abolition of Man, Lewis argues that good education must not merely tear down jungles but

also irrigate deserts. He means by this metaphor that, more than dismantling false conceptions of the world, we must teach people what they are to love. In the novel, Lewis disillusions readers of their mistaken assumptions about evil while showing us a beautiful picture of the good. Good and evil do not exist as entities “out there” but rather are planted and grow within a community through small and gradual actions that assent to or dissent from warring powers. In other words, the small decisions matter. For instance, if we lie to the DMV about whether we drove our car after the registration was expired (not that I’m speaking from experience), we have increased the strength of evil. And if we offer a room in our home to a student for a semester while she figures out finances for college, we have participated in increasing the strength of God’s kingdom. It’s like the Netflix show Stranger Things: the darkness grew stronger or weaker based on people’s actions.

Even better than a show or film that portrays reality with truthfulness, That Hideous Strength teaches readers the necessity of being formed by good culture. Those with all the head knowledge in the world still don’t stand a chance against evil if they have not cultivated a strong chest. Without chests, even those who fashion themselves as “heads” will devolve into beasts. In That Hideous Strength we witness both a community that nurtures a culture of holiness and its opposite, an infernal world that drags down the most dedicated of humanists. Lewis offers an illustrative warning based on Paul’s Letter to the Corinthians: “Bad company corrupts good character” (1 Cor. 15:33). But he also shows us what the church, in its highest ideal, could look like.

Content taken from The Scandal of Holiness by Jessica Hooten Wilson, ©2022. Used by permission of Baker Publishing www. bakerpublishinggroup.com.

Jessica Hooten Wilson is the Louise Cowan Scholar in Residence at the University of Dallas. She is the author of Giving the Devil his Due: Flannery O’Connor and The Brothers Karamazov, which received a 2018 Christianity Today Book of the Year Award in the Culture & the Arts; as well as two books on Walker Percy. Most recently she co-edited Solzhenitsyn and American Culture: The Russian Soul in the West (University of Notre Dame Press, 2020).

FORMA / WINTER 2022 | 21

Excerpt

The great narrative of the Odyssey is not entirely told by Homer. The arch-poet Homer turns the story over to his hero, Odysseus, and it is Odysseus himself who tells of his voyages. In doing so, Odysseus reveals to his audience that he, like Homer, is a poet. But the meta-layers don’t end there. Those who read the work in translation encounter another poet: the translator. Desiring to understand and experience the original to the greatest extent possible, we ask of our translation: Is it faithful? In so doing, we ask the same question of our translators that has been asked for generations of Odysseus: Is the poet faithful to the truth?—a question especially fitting to the tradition of the Odyssey.

While the poet deals in truth, he does not necessarily utilize literal facts. This is likewise true of translations. Like Odysseus, the translator has a preeminent goal: to bring a work home. In bringing poetry into our native language, each translator will choose how tightly to tether to the original. Even when a translator desires a precise and literal rendering, fidelity to the complexity of Homeric poetry can be elusive.

Homer’s poetic craft is masterful to the point of mystery. Homeric Greek can do much with few words, allowing for poetry of depth and dimension dressed in simplicity and economy. His careful control of the elements of poetry—word, meter, and content—leave the translator a great challenge: how to render these three elements in a way that conveys the greatest poetic knowledge of the original. In general, a translator will prioritize certain elements above others, for English cannot fully capture the depth of Homeric Greek, and the translator must make concessions wisely.

A walk through a selection of the Odyssey, comparing translations to the original Greek, may help us see how choices of translation illuminate different aspects of the original poetry and may ultimately help us select translations suited to our particular purposes.

At the heart of Homer’s Odyssey lies the iconic descendus ad inferos, the journey to the kingdom of the dead. Instructed by Circe, Odysseus has learned that he cannot go directly home but must first journey to the underworld to consult the prophet Tiresias, who alone can tell him the way home. This action takes place in darkness. Odysseus travels to where the ancients believed the very boundary of the earth existed, a place where the sun cannot shine. Structured chiastically, the opening lines of book XI begin and end with images of darkness: as the dark ship sets sail, the journeying ways are darkened, and Odysseus and his companions arrive at the place of νὺξ ὀλοὴ—deadly, perpetual night. Eventually Homer starkly contrasts the darkness with the bright spiritual themes we will come to see in this book. But first, Odysseus walks in darkness.

Disembarking, Odysseus digs a pit and pours a libation to the dead. Invoking the dead, he sees the dread shades approaching. Odysseus’ narration translated by Richard Lattimore is,

the souls of the perished dead gathered to the place, up out of Erebos. (11.37)

And a few lines later:

These came swarming around my pit from every direction / with inhuman clamor, and green fear took hold of me. (11.42–43)

The Greek, which Lattimore translates accurately as “of the perished dead,” is,

νεκύων κατατεθνηώτων. (11.37)

Spoken aloud, these two words form a formidable phrase of nine syllables, many of which are long vowels that the ancient rhapsodes would have sung with double length. One cannot rush this phrase in Greek. The three long omegas sound like one long groan. In the original, the audience hears the unsettling groans of the dead before being told five lines later of their inhuman clamor.

Robert Fagles, whose translation flows beautifully when read aloud, phrases this as,

up out of Erebos they came, flocking toward me now, the ghosts of the dead and gone . . . (11.41–42)

Peter Green takes a similar approach:

There came up out from Erebos the shades of corpses dead and buried. (11.36–37)

Though idiomatic, Fagles’ phrase “dead and gone” slows down the pace, and partially replicates the lengthened, lower register sound of the original.

The first soul that speaks to Odysseus is his companion Elpenor, whom Odysseus and the others left unburied on Circe’s island after an accident took his life. Elpenor implores Odysseus to bury his body lest, unburied, it provoke the wrath of the gods. His instructions to Odysseus, translated with clarity by Peter Green, are,

Heap me a burial mound by the shore of the grey sea, / for those yet unborn to learn of an unfortunate man. / Do this for me, and set on my tomb the

24 | WINTER 2022 / FORMA

oar / with which I rowed, when alive, among my comrades (11.75–78)

In the original, “Do this for me, and set on my tomb the oar” is,

ταῦτά τέ μοι τελέσαι πῆξαί τ΄ επι τύμβω ἐρετμόν. (11.77)

Fagles chooses the command “plant” rather than “set,”

Perform my rites, and plant on my tomb that oar / I swung with mates when I rowed among the liv ing (11.85–86)

as does Lattimore,

Do this for me, and on top of the grave mound plant the oar / With which I rowed when I was alive and among my companions. (11.77)

Though πῆξαί does mean to set or plant, it can also imply a more repeated action than either setting or planting, more like making something fast by hammering a few times. The phrase πῆξαί τ΄ ἐπὶ τύμβω ερετμόν, spoken aloud, sounds like a steady metrical drumbeat. In the original, this phrase heard with the next line, “with which I rowed, when alive,” recalls the action of a boatswain keeping time, hammer in each hand, striking the beat as the oars of the rowers rhythmically strike the water. Lattimore’s translation follows Homer’s hexameter. While it approximates the pace of the original and lends a foreign ethos to his translation, it is a meter not naturally rhythmic in English. Here, Green and Fagles imitate in English the rhythmic nature of Elpenor’s instructions in the original Greek. We can picture Odysseus pitching Elpenor’s oar upright in an action reminiscent of the time-keeper. Elpenor, whose name incidentally closely resembles ἐλπίς, hope, exhorts Odysseus to remember; to remember him while we remember the passage of time itself.

Next, Tiresias speaks to Odysseus, this conver-

sation being the raison d’être of this journey to the underworld. However, before Tiresias speaks, Odysseus sees the soul of his dead mother, Antikleia, and, unaware until this moment of her death, breaks into tears. Tiresias speaks for thirty-eight lines in the original, telling Odysseus of his homecoming, including a warning to not harm the pasturing cattle of Helios and that trouble awaits him in his household. After this long speech, Odysseus, the poet, a man whose epithets are prefixed with many- and much-, surprisingly replies with a one-line statement in the Greek, with no subsequent questions about his homecoming. Both Lattimore’s and Green’s line-by-line translations replicate the surprising brevity of the original. Green’s translation:

Teiresias, it may be that the gods have spun this thread. (11.139)

While Odysseus’ response in Green’s translation could be understood as thoughtful or wondering, Lattimore’s translation relates this as conclusive and practically dismissive, closer to the mood of the original Greek:

All this, Tiresias, surely must be as the gods spun it. (11.139)

Odysseus then asks about his mother, specifically why she sits in silence. Tiresias responds, in Green’s translation,

Whosoever of those that are dead and gone you permit / to come up to the blood will converse with you truthfully; / but any that you refuse will go back to where they came from. (11.147–49)

In this, Homer begins to reveal a crucial truth: the most important knowledge is found among the dead, among what is dead and gone, but only Odysseus can give it voice. Antikleia sits in silence until Odysseus gives life to her voice in the form of blood.1 Odysseus has traveled to the underworld to learn of his future, but he remembers that it is the past and the present

1. Antikleia’s name means the opposite of kleos. While kleos is typically translated as fame, its root is to hear. Kleos means that which is heard, and so, that which is famous. In the instance of Antikleia’s name, it is more likely that the significance hearkens back to the root meaning, she who is not heard

FORMA / WINTER 2022 | 25

he does not know. In a triumph of what is past and familial, Odysseus dismisses the seer and magnifies his mother. After partaking of the blood, she speaks first, addressing him simply as τέκνον ἐμόν, my child. Green’s translation,

My child, how did you penetrate this murky darknes while alive? (11.155–56)

Antikleia is unhappy to see Odysseus here in this place of darkness. In the original, Odysseus responds in uncharacteristically simple language, which enhances the pathos of this encounter. Μῆτερ ἐμή, my mother, he says. Fagles, Fitzgerald, and Lattimore translate this more formally as mother, but Green captures the simplicity of Odysseus’ language and the intimacy of the moment with,

My mother, need brought me down here to Hades’ realm: / I had to consult the shade of Theban Teiresias. (11.164–65)

Having no questions for Tiresias about the future, he questions his mother first about how she died, next about his father and son, then about his wife and her fidelity to him. In the original, Antikleia’s response immediately brings Odysseus hope. She leads with the news of Penelope’s endurance, answering his last question first; and after her first few words, we understand that Penelope is waiting for him, Καὶ λίην κείνη γε μένει τετληότι θυμῶ. Green’s and Lattimore’s translations accurately reflect her motherly instinct to quickly comfort him,

Truly indeed she holds on with steadfast spirit. (11.181)

And Lattimore’s,

All too much with enduring heart she does wait for you. (11.181)

Fitzgerald’s translation is beautiful, though it does not make perfectly clear the good news until the second line:

Still with her child indeed she is, poor heart Still in your palace hall. (11.204–5)

In her final words to Odysseus, Antikleia tells him to hurry towards the sunlight and to remember all that he has seen so that he may tell his wife. Green’s translation:

But quick, hurry back to the light now, with all these things / stored in your mind, to tell your wife hereafter. (11.223–24)

The word that both Green and Lattimore translate as “hereafter” is translated by Fagles as “one day,” and Fitzgerald as “in after days”; all fitting translations for the original μετόπισθε. Yet there is a certain timelessness about the word hereafter that hints of retellings and calls to mind the work of Odysseus, not only the husband but the poet.

At some point, Odysseus pauses, and we remember that he is relating this story to the Phaiakians in the hall of King Alkinous. Here also, darkness has fallen. It is night, and the halls are dark and shadowy, and everyone sits in silence, paralleling the land of the dead. Queen Arete2 speaks first, breaking the silence. Green translates the Queen’s words,

Phaiakians, how does this man’s character strike

2. Queen Arete’s name may mistakenly be understood to mean excellence or virtue, but her name in Greek is spelled Αρήτη, which is a different word meaning the object of one’s prayers, the one prayed for.

26 | WINTER 2022 / FORMA

Though some translations are more interpretative than others, all translations are acts of interpretation, offering to us truth as prioritized by the translator.

you? / His looks, his stature, his equable inner mind? (11.336–37)

The phrase that Green translates as “equable inner mind” is translated as “inward poise” by Fitzgerald, and “the balanced mind inside him” by Fagles. Lattimore chooses “the mind well balanced within him”:

Phaiakians, what do you think now of this man before you / For beauty and stature, and for the mind well balanced within him? (11.336–37)

While Green, Fitzgerald, and Fagles offer elegant translations of this phrase, Lattimore’s translation is the most thought-provoking. The original Greek is φρένας ένδον ἐίσας. The word ἐίσας is the same epithet that Homer uses in both the Iliad and the Odyssey to describe ships. Homeric ships are well-balanced, swinging evenly on the keel, maneuvering forward and backward. Shields are also well-balanced. Where this word ἐίσας appears, Lattimore does not vary the translation; he is comfortable replicating Homer’s repetition. While an English translation may not be able to bear the full repetition found in the original, Lattimore’s tendency to reflect this repetition helps us to perceive indirect comparisons; Queen Arete is likening Odysseus’ mind to a ship, the only means of returning home for the Greeks who fought in Troy, and a symbol of salvation. Despite his mother’s final advice to hasten back to the light, it is Odysseus’ nature to want to know more. After speaking to the wives and daughters of heroes and Agamemnon, he sees Achilles, the greatest of the Achaians, who reveals that he would rather be a hired hand for a landless man than lord over all the perished dead. Then Achilles asks about his son: Was he a champion in the war? After hearing Odysseus praise his son as a champion in both war and council, Achilles walks away. Odysseus describes the manner in which Achilles leaves, translated by Fitzgerald,

But I said no more, / for he had gone off striding in the field of asphodel, / the ghost of our great runner, Akhilleus Aiakides, / glorying in what I told him of his son. (11.639–42)

Lattimore translates these latter lines as:

So I spoke, and the soul of the swift-footed scion of Aiakos / Stalked away in long strides across the meadow of asphodel, / Happy for what I had said of his son, and how he was famous. (11.538–40)

Lattimore’s translation here is faithful to the words in Greek. However, Fitzgerald weaves in what tradition believes to be true about Homer. Long strikes, μακρά Βιβᾶσα, symbolize victory and glory. In the Iliad, Hektor took μακρα βιβας when fighting against the Achaians by their ships, after being assured of victory by Apollo (Iliad, 15.305). Fitzgerald here deviates from the Greek, opting for the word glorying, which is not in the original, rather than Lattimore’s happy, to associate these steps with battle victory; it is a thoughtful interpretative choice and well-grounded in context.

Though some translations are more interpretative than others, all translations are acts of interpretation, offering to us truth as prioritized by the translator. For those who would appreciate more of the interpretative work done for them, Fitzgerald’s translation of the Odyssey is both poetic and insightful. Lattimore, on the other hand, will not disappoint the student or scholar who does not know Homeric Greek but wants to be able to quote Homer accurately. Fagles and Green are somewhere in between, with Green being closer to Lattimore in his precision, while still being delightfully musical. For a well-balanced poetic experience of the Odyssey, bring one translation home this year, then commit to a different one hereafter.

Monique Neal lives in Richmond, Virginia, with her husband and homeschools their four children. She is a CiRCE Certified Master Teacher and is a student and teacher of ancient Greek as a living language.

FORMA / WINTER 2022 | 27

Jonathan Pageau is an icon carver, creating images based on the medieval canon of images for churches and people all over the world. This has led him to study the way symbols embody meaning, a field of study that he explores on his YouTube channel and blog. In particular, he often contemplates how the symbolic structures of our ancestors can inform our world today. Recently, he sat down with FORMA’s editor Katerina Kern to discuss the recurring themes of his life’s work.

Why do you speak so frequently on symbolism?

In the past two hundred years, since the Enlightenment, or maybe the Renaissance, we’ve moved towards a materialist way of understanding the world. We’ve gained a lot of power, material power, you could call it, through analysis and science—through quantifying things, calculating them, measuring them, predicting them. It’s quite impressive. But what seems to have happened as a side effect is we’ve lost some sense of purpose and ultimate meaning, some sense of the reason why we are bound together as communities, as families, as cities. All of which seem to be fragmenting around us today. People don’t know what is real, what is true anymore. And I believe that this is due to looking only at things that you can analyze and quantify, rather than looking at their purpose. So this symbolic way of seeing the world is a way to recapture these meanings, to recapture the mystery behind communion, families, and cities.

Symbolic thinking can help us understand how facts can be strung together in patterns, which we call stories, and in images, which take a bunch of stuff, bring them together in a frame, and help us see that they are one within that frame. All of this can help us move towards meaning again.

In your work, you frequently use terms like “truth” or “reality.” What do you mean by these?

Well, there’s a way in which we reduce truth to something like factuality, which is that if something exists, and we can touch it, we can count it, we can predict it, then that’s true. But there’s a deeper truth, which is hiding behind that, which is something

like: Why do we care about that in the first place? Why do we care enough about something to name it, to give it an identity and to engage with it? And so once we start thinking that way, we come closer to truth. We could call that value. You can understand it as something like an arrow that is aimed truthfully, that hits its mark. The arrow is true in that sense as well as a factual sense. This is the higher form of truth.

I think we’ve come to a point where it’s inevitable that we look at that higher form of truth again. This will then lead us to something like virtue and love. For we understand that the world exists in a certain manner through love, which is the capacity for us to engage with someone or something and bring it close to us without destroying them or annihilating their individuality, but rather to bring them into this relationship of unity and multiplicity simultaneously.

If symbols name things and Genesis tells us that naming things takes dominion over them, how do symbols express things without taking dominion over them?

In the notion of dominion we can understand the idea of hierarchy. Every identity has an aspect of it which is central and visible. When lighted you can see it, but that aspect of reality then could go in different ways. It moves in one direction towards the margin where it starts to break down, to manifest exceptions and strangeness.

Think of a chair. You know what a chair is. But once in a while you’ll encounter a chair that’s not necessarily a chair, it’s like a chair and unlike a chair. Perhaps it’s a bench. It’s in-between. And that’s totally okay. There’s room for that in-between in identity making, if you understand hierarchy.

Then there’s also a manner in which the identity points to something which is hidden, which is something like the mystery of the chair, which can’t be contained in its particulars. This is harder to talk about, but it has to do also with the purpose of the chair. So you can say that the purpose of the chair is not in the chair, the purpose of the chair is in our use of the chair. But there’s an even higher purpose of a chair, which would be to be something like a throne, let’s say, for the highest thing, the seat of the

30 | WINTER 2022 / FORMA Interview

highest thing. So the seat of a judge is getting closer to what a chair is in its mystery. But you can’t totally name it, you keep going higher and higher. And then you come, ultimately, to the notion of the throne of God, which is the heavens themselves. So there is a cosmic throne, a cosmic purpose for the chair that we use to eat our dinner. But it’s somewhat hidden, even in the chair which is physically present. Understand this in the chair, and you can understand the manner in which the heavens are the throne of God.

Do you think about this in Platonic terms?

I don’t necessarily use Plato. I use mostly the church fathers. One of the differences between Plato and the way the church fathers described it, especially St. Maximus the Confessor, is the church fathers understood man as the crux of this. One of the problems with Plato is that he has these forms up there. And then he has these shadows of the forms on earth. But where are the forms? Maximus says that the laboratory of the forms is man. So the human is the place where the forms are gathered in. And so the purposes of things come through human purposes. And this is really important, because it comes down to the manner in which you perceive things.

Right now, in terms of cognitive science, we realize that we cannot abstract ourselves from the intelligent beings that we are when we look at the world. We look at the world through this lens of being human, and having human desires and human goals, and this, for the church fathers, is not at all a problem. Because man is the image of God, so the human gathers these logoi (as they would call them), the different purposes of things, in himself. And then he offers them up. So it’s through man that they’re offered up. The reality of the human chair can help you understand the higher aspect of the throne of God, you could say, but it’s really through man. It’s through a form that we

are using and embodying and engaged with. So all the images we use for God are human images. That doesn’t diminish God, it means that all of these images that we gather into ourselves are projected up. And that’s totally fine because we are the image of God. This eliminates the problem of Platonism so we don’t have to think of a world of forms separated from the intelligence in man; it’s gathered into us.

This sounds like phenomenology. Do you think of this that way?

Yes, it is similar to phenomenology. I believe that Heidegger opened a door but didn’t have a full intuition of what he was opening. But I do think that one of the things phenomenology does is help us at least to re-enter this space of being. For example, Heidegger’s notion of dasein (care) is very useful, because it’s the idea that we see that which presents itself to us as that which we care about; it is the capacity for attention.

The difference between phenomenology and this understanding of meaning I’m describing is in the way we talk about it. We (the church fathers and I) are bringing it back into a type of metaphysics that includes the idea that humans exist in the image of the Divine pattern. It’s not just this arbitrary thing, it is actually the pattern of reality, and therefore it gives us access. If we accept that phenomenology and look up, then all of a sudden we can understand mysteries about the way in which the world lays itself out. So it’s not just about analyzing phenomena through the lens of experience, but it has a transformative aspect, which I don’t think Heidegger would have necessarily talked about.

Ultimately, it’s an offering that we give. We offer ourselves and all that we gather into ourselves to God so that the offered reach their full potential. And so then the dominion that we have over the world is not this cold dominion that we see in modern science and

FORMA / WINTER 2022 | 31 Interview

modern technology, but rather a caring dominion. It gathers things and participates in them and makes them beautiful, so that they do become something like the body of God.

That’s beautiful. I’m wondering, then, if someone perceives what they choose to perceive, or what their priorities and their vision allow them to see, and then they tell a story, is it possible to have a false story? Is fiction possible? What makes stories true or false?

Again, hierarchy is the best way to understand this. The human person has different faculties, and those faculties are organized in a hierarchy. At the top, you have something like a spiritual intuition—spirit, perhaps. The spiritual capacity is to encounter higher things: God or higher aspects of reality. Then you have something like reason, which weighs the good and the bad. Then lower still you have something like your desires and your more irascible nature: your capacity to get angry, your capacity to be hungry for different things. Consequently, you have to purify your attention. Because your attention, especially in this world, tends to move down towards those lower aspects. So, in that sense, you can say that there are false stories that we engage in all the time. We have idols, which are usually these images of our lower aspects, but they can be derived from our reason as well. Those would be the stories which would be more false as you come down the hierarchy. But there’s nothing wrong with the desires if they’re properly organized, it’s only when you attend to them completely that they become something like idols. You can see that in terms of story. Most will be something like going down and up. Almost every story is about that: losing control, losing some higher aspect, facing a problem, facing a question, facing a challenge, then fighting it out and regaining that higher place.

So the hero’s journey is essentially every story?

Pretty much, but the hero’s journey makes it overly complex. You can just understand it as—situation, problem, resolution or non-resolution. That’s the big cosmic story, right? In the Bible, from the formation

of the world and the fall to the New Jerusalem, it’s down and up the hierarchy. There are stories of going up and down, but those are to return up again. Like Moses goes up the mountain, gets the law, and brings it down to the people [so that all can return up again].

If it’s just left at the bottom, I imagine that would be a tragedy?

Tragedy would be when things unwind. The image of Pentheus in The Bacchae is one of the best examples. His attention is not on the right place, so he ends up being a little too curious about the wild women in the wilderness and he’s literally ripped apart by them. That’s at the bottom of the hierarchy. It’s hell. Hell is being ripped apart—falling into chaos. The problem with these passions at the bottom is that we become slaves to them, and usually to several of them, and they fight amongst each other and we feel as though we’re ripped apart.

So you talked about these patterns. Which patterns do you think are most important for our culture now to understand?

This is going to surprise some people, but I think that right now the most important one to understand is the pattern of monsters. Our world is pretty much obsessed with that symbolism. If you just look around you, you’ll see it everywhere. If we’re not able to understand them, we won’t be able to see both their danger and their opportunity.

It comes back to the problem of identity and exceptions. So you have chairs, and then above them you have the throne of the judge or the throne of God, and at the bottom you have monster chairs. And those exist like broken chairs. They aren’t fully chairs—they’re chairs that are in between “chair” and something else.

These exceptions are part of the system, but they always appear at the margin of an identity. Imagine a tribe, let’s say. A tribe has its own cohesion, its own unity. And then once in a while someone will marry outside the tribe, or someone will come in from outside that is not part of the system. That person will be on the margin, which is totally fine. But one of the problems we have right now is that we’re obsessed

32 | WINTER 2022 / FORMA

Interview

The pattern of Genesis is really a map of reality that can help you understand the manner in which the world works. Here we see this powerful creation of two extremes, Heaven and Earth. They slowly move towards a middle, wherein lies man as the union of breath and dirt and dust—the union of the chaos below and the spirit above.

with the exception, and so all our social discourse is about glorifying the exception in every way. But this accelerates fragmentation, because you can’t have an identity full of exceptions. They’ll end up ripping each other apart.

I think understanding that can help us find a more balanced relationship. The exception, or the fringe, is very important in the story. In the Bible, for example, it’s pointed out often that you always have to leave a fringe on any identity. You have to leave the corners of the field untilled so the stranger can come and gather it, and you have to leave a fringe on your vestment; you can’t tie everything up. You have to leave a little bit of chaos on the edge. Because tying everything up is part of dying; it’s actually a form of asphyxiation, you could say. So you can’t have a closed system; you can’t have completely closed identities.

That makes sense on a large scale—the image of the margin and the need for that in society as a whole. But what about the individuals within the margin? Should we not try to enfold them into the whole because society needs the margin?

There are a few ways to understand this. One is that people are not one thing. A homeless person is not just a homeless person. He’s also a man and Joe and the son of someone and the brother of someone. We all have some aspect of ourselves that’s of the margin.

Now being on the margin has advantages and disadvantages. We tend to think that the margins only have disadvantages, but that is absolutely not true. Being on the margin has advantages if you can perceive it properly. And so to the extent that as a person you have some marginal aspect to you, you have to try to make the most of that.

You speak of “the upside down world” a good bit in your work. When you talk about people trying to make the margin a part of the center, is this what you mean by “the upside down world”?

One of the problems of the modern world has been this idea of equality. It’s a very messy concept. There are so many vectors in a human person that this borders on absurdity. What do you mean by equality? Equal intelligence, equal in height, equal in attractiveness, equal in money, equal in skills? There’s no way in which all humans can be equal in all vectors. And because humans are not equal, and can’t be equal, in the desire to make things equal, they always have to overcompensate. A good example is the trope of women being as physically strong as men. That’s just not true. It’s true in the exception, but it’s not true in the pattern. Because it’s untrue, in order to bring the point about, you actually have to overemphasize your point. So the idea is not to show that women are equal to men, you have to show that they’re stronger than men. All you’ve done in your search for equality is turned the world upside down and repeated the same pattern in its inverse. This is problematic because it’s so unnatural that it brings people close to something like psychosis. Why force people into roles that are so unnatural to them that they have to embody their own opposite? If you just let things be, there would always be women that would be more masculine, and there would always be men that would be more feminine, but you don’t have to make it a goal to invert the patterns across all society.