The Yard volume 13 issue 3

The Yard volume 13 issue 3

White

White

12

16

22

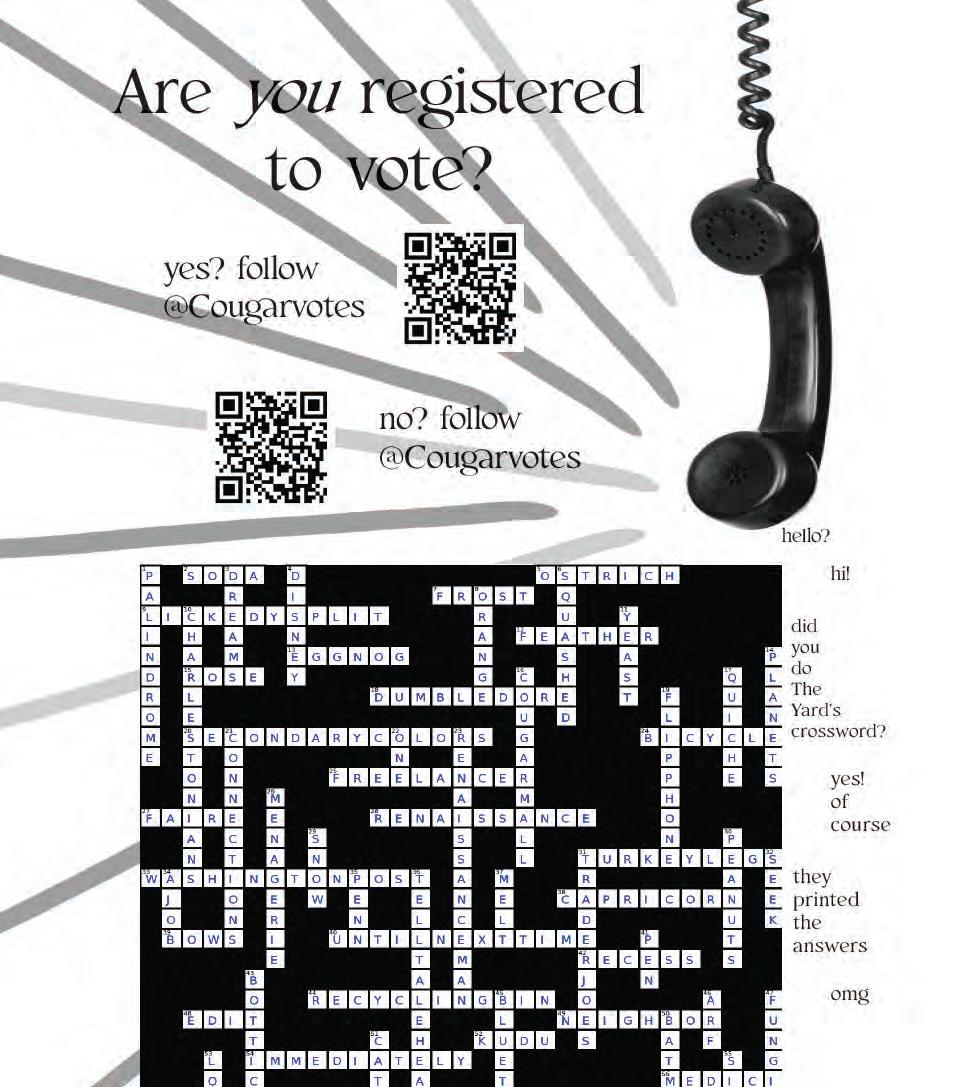

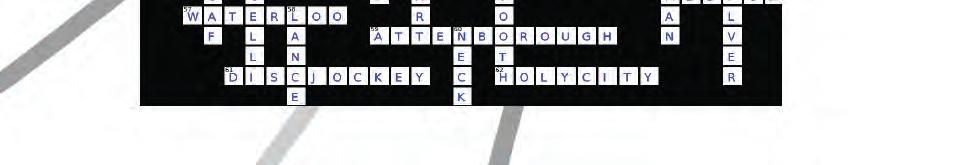

The Yard’s Spring Crossword

34

The Letter Men: An Unlikely Story of WWII Love

The Toxicity of Tech

The Evolution of Drag

Dear readers,

ank you for taking a look into our magazine! Volume 13 Issue 3 is e Yard’s very rst Black and White issue. Our goal for this magazine was to curate visual art and written articles that experiment with the lack of color.

As a sta , we nd so much creative freedom through this magazine. However, we wanted to challenge ourselves and our volunteers to discover what a modern magazine could look like without color at the center of its lure. e content of this issue covers a vast range of interests: love during the time of World War, drag over the centuries, black and white lm photography, technology and its pitfalls. As always, I am impressed by the amalgamation of things our volunteers and sta took an interest in documenting during the production of this magazine. It has produced a very memorable issue.

Cistern Yard News has always equipped me with the tools to discover what I am passionate about and the freedom to experiment with those passions. As Editor, I have loved being able to continue to understand my love for design and journalism and extend those opportunities to the campus. As my sta and I nish this issue and begin work on our last magazine together, I am acutely aware of the opportunities Cistern Yard has given me over the years. I am forever grateful for this organization’s dedication to studentexpression and the community oriented environment fostered by sta before me.

Graphic Designers

May Lebby ompson

Alix Averitt

Camila Carrillo-Marquina

Devin Dehollander

Sally Pham

Madison Como

Sabrina San Agustin

Photograhpers

Alix Averitt

Camila Carrillo-Marquina

Marina Silvestri Writers

Eva Neufeld

Devin Dehollander

Julia Bianchini

Caz Kopf

Anna Rowe

Models

Liza Malcolm

Barb Malone

Jack Watson

Lara Odell - Editor in Chief

Alix Averitt - Creative Director

Camila Carrillo-Marquina - Head of Photography

Madison Como - Managing Editor

Anna Rowe - Opinions Editor

Devin Dehollander - City News Editor

Blakesley Rhett - Features Editor

1. an ageless boy

3. additionally

8. month of presidential election

10. opposite of is so

12. a cookie that fits this mag’s theme

17. winner of Best New Artist at the Grammys

21. bitter beer

2. South Carolina presidential candidate

18. second queen to go home in RuPaul’s 16th season

22. You’ve Got ____

24. first science fiction film

28. where literary discussions take place

29. mix of pink and purple

30. book of transactional records

31. performer at the 2024 Super Bowl

32. intellectual property

4. annual book of weather and astrological predictions

5. a bear that fits this mag’s theme

6. what you are doing right now

7. after Millennial

9. shortened name of a print publication

11. site for higher education

13. when people act like sheep

14. holder of written secrets

15. where you can always find a copy of The Yard

16. jeans material

19. King of Thebes

20. a French term for a popular type of American media in the 40s and 50s

23. cough reliever

25. siezed illegally

26. treat for kitty

27. City News Editor for The Yard presidential what

scan this

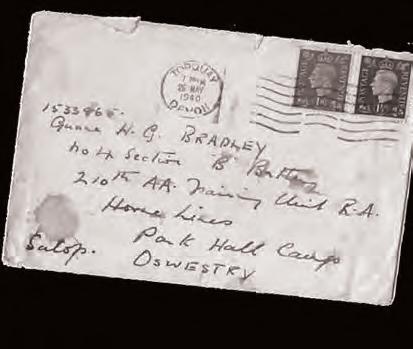

It was a breezy day in 2008 in Brighton, England when a home clearance company emptied the house of one Gilbert Bradley. Mr. Bradley had recently passed away, and without a spouse or surviving kin to his name, his property was purchased by a local company and its contents distributed to di erent vendors. Among these contents were a series of old letters written between Bradley and one of his sweethearts in the years during and a er World War II while stationed overseas.

Imagine being inside that old home. Fine chinas line the sides of dusty cabinets. Black and white photographs watch you walk down the creaky hallways. You nd Bradley’s letters in the study, old, yellowed pieces of paper sent between a soldier and his sweetheart over half a century ago. e handwriting is sloppy, and what little of the letters you can make out isn’t that interesting- they mostly contain correspondences about living conditions or accounts of how much the two lovers missed one another.

You nish clearing out the house and move on with your life. e clearance company sells the letters o to a local dealer which promptly puts them up for sale on eBay without much thought. ey’re old letters from

some guy’s house- nothing more. ey might have held some value to the man’s family if any had survived him, but otherwise, they seemed worthless to anyone who wasn’t an interested historian.

As fate would have it, though, a historian would take interest. Mark Hignett, a curator for the local town museum, bought a small handful of the letters, believing them to be nothing more than a curious look into the life of your average wartime couple. It wasn’t until he got to work transcribing them, though, that he realized just how special they were. At the end of every letter, Bradley’s sweetheart signed “G”. At rst, Hignett just believed this to be a shorthand way to sign o the letter, but he soon learned that Bradley’s lover was signing an initial for one very speci c reason- Bradley had been writing to a man, not a woman.

It would be an understatement to say that being queer during the Second World War was di cult. Even if you weren’t enlisted, loving someone the same gender as you in the 1930s and 40s could easily result in being shunned by, or in some cases even physically attacked by their community.

And contrary to the narrative we’re o en told, these relationships did exist in abundance, as evidenced by other letters similar to those between Gilbert Bradley and his lover, Gordon Bowsher. We don’t know how many couples hid away in secret, shielding one another from the cold world they found themselves in, but the precious few stories we have of this phenomenon paint a vivid picture. We nd beautiful little instances of queer love crystalized across history in stories just like Bradley and Bowsher’s. I want to look at the letters these two men exchanged during the course of World

War II and talk about why they stand out to me so much.

e two soldiers met at a houseboat party in 1938, a mere year before the beginning of the war, and they hit it o . Gordon was a gentleman from a wealthy family; his father ran a shipping company and owned tea plantations. When combat broke out, the two men were dra ed. ey wrote to one another from the beginning of the war, in 1938, until 1945.

So, what makes their letters historically signi cant in the rst place? A er all, the actual contents of the more than 600 correspondences between the two men are mostly banal- they talked about their everyday lives and wrote gushy love notes to one another, but that’s about it. And they aren’t important just because they highlight an LGBTQ+ relationship, either. Rather, it’s the unique circumstances surrounding the men’s relationship that make it so interesting and so unlike others of the time, even other queer relationships.

e rst unusual aspect of the letters is their existence in the rst place. Nearly all queer couples of the time would destroy evidence of their relationship- for instance, in one correspondence, Bowsher writes to Bradley, saying “do one thing for me in deadly seriousness. I want all my letters destroyed. Please darling do this for me.” Had it not been for Bradley’s commitment to preserving these letters in his Brighton home, we would never have known of his relationship with Gordon Bowsher. It’s chilling to think how many couples have intentionally erased their mark on history for no practical reason other than fear of discovery. erefore, the collection of love letters found in Bradley’s home is an incredibly rare archaeological nd, even for the period.

in a homosexual relationship during this time was a court-martial o ense. Dubbed “gross indecency”, participation in this illegal activity could mean dishonorable discharge, jail time, and even execution in certain cases for British soldiers. So, to discover a relationship between two men that not only has surviving documentation but also has a happy ending is a one-to-amillion shot.

And the happy nature of the men’s relationship was not lost on Andrew Vallentine, a queer lmmaker who directed the 2021 short lm ‘ e Letter Men’ based on Bradley and Bowsher’s lives. e lm stars Garrett Clayton and Matthew Postlethwaite and follows the story of the two men’s meeting and subsequent separation as a result of the war. It’s an excellent lm thanks to its great lead actors and historically accurate sets, one that paints a beautiful vignette of a wartime love ing. In describing how he wanted the movie to be, Valentine notes the tranquil, happy nature of the men’s relationship, saying “in a lot of LGBTQ+ cinema, we tell our worst stories, some of the worst things that have happened to us from over the years. In ‘ e Letter Men,’ we didn’t explore hate crimes, we didn’t explore people being shunned…. We really just told the story of these two men in love.”

e second reason the letters are strange, though, is due to how surprisingly light-hearted and whimsical Bradley and Bowsher’s relationship was. So many queer narratives end in heartache, especially those from bygone eras, that it’s strange to nd a story of two normal people just… falling in love. Being involved

I believe this is the power of Bradley and Bowsher’s letters, and is the reason why their story resonated so deeply with me. All too o en, the stories of queer people, and those of soldiers, are ones of tragedy, as if the mere act of being born gay or choosing to enlist in the army immediately dooms you to your fate. You get put on a pre-determined track, one that may have its fair share of positive moments, but one which ultimately will end in heartache. Plus, it doesn’t help that those who do manage to escape the world’s expectations and live happy lives are the only ones we don’t hear about. Stories like Bradley and Bowsher’s remind us that happiness IS real, and that it IS possible. It warms my time-hardened heart to think that, even during the largest armed con ict in human history, within one of the most homophobic times in recent memory, love blossomed. And if two people can be happy under those circumstances, maybe there’s hope for us all.

Two seemingly unrelated things, yogurt and the digital age, now represent one of the rst self improvement trends of the new year. e icelandic yogurt company Siggis is o ering customers who believe participating in a digital detox will change their life a chance at their 10,000 dollar cash prize, and three months of free yogurt of course. When participants are selected, they agree to lock their phone in a box for the month and rely on a ip phone as their only source of digital communication. e company hopes people can nd a di erent way to spend the 5.4 hours a day the average person spends with technology, but like the many other resolutions people commit themselves to in the new year, facing phone addiction can be harder than it seems. You can turn o screens and unplug devices in an instant, but it takes much longer for your brain to accept this change in lifestyle. When vowing to spend less time in front of screens or even give up devices completely, people don’t think about how integrated technology is in our brains, in our lives, and in our society.

A high level of interaction with technology has been a part of daily life since the early 2000’s, meaning the majority of Millennials and Gen Z have had access since their early childhood. It has become standard for TVs to ll living rooms, computers to reside in o ces, and phones to be kept close by at all times. e integration of these devices in daily life meant the integration of these devices into our childhoods. Initially, kids used screens for education and entertainment. ey learned their ABC’s from educational Youtube videos and built friendships with animated characters on TV. Tweens and teens gain access to new devices, introducing them to the concept of social media. ey can talk to people all over the world, learn and obsess over the newest trends, and post content online for an audience much larger than just friends and family. e use of technology at di erent ages is becoming standard and these experiences are now parallel with other developmental milestones. e age where kids are expected to interact with their

peers is now also the age they interact with TV characters and online gures. e age where teens and tweens start to look to others for approval is also the age where they begin using social media to accomplish that goal.

e moment where teens begin to use social media is such an important milestone, and it o en lines up at a time in their life where they are experiencing a lot of emotional changes and vulnerability. As they are maturing, teenagers experience a strong desire to t in with the people around them and relate to their peers. With access to social media, they are now comparing themselves to the millions of other social media users instead of just the people in their schools and communities. e most popular users,now better known as in uencers, have created a standard to what our day to day lifestyle should look like. For most people but especially young children, these expectations are completely unrealistic. Teens exhaust themselves trying to look, act, and live like the people they see online and then feel defeated when they fail to achieve such impossible standards. Even if these young users are not trying to emulate the people they see on social media, they can encounter hate comments, cyberbullying, or grooming behaviors for simply posting personal content. No one would think to send a tween or teen into the world by themselves, but by using social media, they are experiencing the same level of interaction with strangers, and yet not many people have questioned its safety until recently.

Social media and device usage seems so integrated into our daily life that it makes sense why society didn’t ask questions about the safety of these devices and the e ects of their prevalence. Technology is responsible for managing the many di erent aspects of our lives, so looking into and admitting its aws would disrupt so many of the systems currently in place. Also, the majority of technological advancements we rely on today are all fairly new, so it has taken time for research to emerge on the mental toll excessive technology use has on our health. But as research has begun to emerge, scientists have found that one of the reasons technology has caught on so well are their addictive properties. When people are using technology or devices, the brain releases dopamine which makes your body feel a sense of temporary pleasure. Kids and adults alike gured out from the creation of early technology that using these devices is exciting and fun- so fun nobody wants to put them down. Of course parents are go-

ing to give their kid an iPad to settle them down and distract them; the child likes the device and the parents know the iPad is guaranteed to work thanks to that dopamine release the child desires. Even for adults, the psychological response to the dopamine release is enough to forget about workplace stress and whatever else you care to forget in your personal life. But as parents and kids clung to their devices more and more, the unnatural source of happiness has begun to alter the way our minds work permanently.

and other so wares made it possible for classes to meet and for us to learn again. Even though society has been increasing their interactions with technology and social media for over twenty years, things have become much more extreme in the past four years as a result of the pandemic. Covid presented a lot of modern problems and technology was readily available to provide modern solutions.

As more scienti c research has centered around obsessive device usage, there has been more and more similarities between the inability to put down devices and the inability to quit other addictive substances. Studies have shown that the speci c way dopamine is released while using devices can alter the structure of the brain overtime, like changes experienced as a result of drug or alcohol addiction. e prefrontal cortex is changing, damaging its decision-making abilities, emotional processing systems, memory, cognitive function, and stress management systems. Some of the direct e ects of these changes in the brain include di culty concentrating, irritability, loneliness, increased anxiety, and other issues that can impact the way kids and teens behave in their day to day lives. A lot of these issues relate to how well kids can do in school, how they interact with others, and how they are developing as people in society overall, but these issues are also a ecting a larger audience than just kids. When devices were rst starting to be introduced, they were seen as a luxury for adults to consult for information and for families to use as entertainment. is minimal interaction with devices can be sustained for a longer period of time without causing permanent e ects. But now the brain is a ected faster and more drastically as people consult devices and technology for virtually everything they do.

One of the main reasons people consult devices is to stay connected to people all around the world. When Covid put restrictions on our usual way of life and our connectivity with the people around us, technology created solutions that provided a sense of normalcy. We weren’t allowed to visit our friends and family so we turned to Facetime to keep connected. e stores were too dangerous so grocery delivery apps and Amazon gured out how to bring us what we needed. When we couldn’t go to school, Google Meet, Zoom,

With all the negative e ects of excess technology use, it seems surprising that more people aren’t making an e ort to cut back until you think about all the aspects of daily life that require some sort of technology usage. As industries look to advance and streamline their production processes, incorporating technology almost seems like second nature in this age. Our careers are managed with apps, we customize and control our homes with apps, our daily errands are made easier with apps, and when we need to relax from the stress of the day, we turn to other apps for entertainment. Apps and devices have also started to change the culture of many aspects of our society. When technology was rst being introduced into the workplace, the equipment was expensive and inaccessible to the public so employees would only be interacting with those devices at work. Now, employees are encouraged, or sometimes expected, to continue working a er their scheduled hours, something which has been made easier with devices like laptops and company management so ware. It creates a culture where overworking is celebrated which is connected to the increase in adults addicted to their technology. Even for those who make an e ort to manage work-life balance, technology is such an available resource for unwinding and ignoring problems that it still manages to have such a strong prevalence in daily life.

All of those factors give Siggi’s digital detox strategylocking your phone in a box for the month- a high failure rate. Immediately changing such a large part of your life instead of easing into change gradually is what holds people back from actually being able to detox from technology. Making small choices throughout the day to nd screen-free ways to accomplish your daily responsibilities can have such a positive impact on your well-being that it’s worth the extra e ort. In a society that forces an access to digital interaction, a large corporation promoting taking a break from devices is a step in the right direction.

Your favorite crime podcast just dropped a new episode, this time about a proli c serial killer that ravaged the streets of a small town. You religiously listen to every twist and turn the story reveals, silently judging the victim for not hearing the glass break when the perpetrator breaks in. You feel slight relief that you haven’t found yourself in this type of situation. As the episode concludes, no matter how violent and disturbing it might have been, you continue about your day. You forget about the victims and what they went through; that the story you were told didn’t include characters, but people from real life, and how much it has a ected the families and friends of the victim. True crime podcasts, and its sister, true crime documentaries, have skyrocketed in popularity over the past few years. We all have an innate curiosity towards mystery and the abnormalities of human behavior. We are disgusted at how a person could commit such heinous crimes, yet are still engrossed in every episode of podcasts released.

e phenomenon of true crime originated when Truman Capote published “In Cold Blood” (a great read by the way) in 1964. e book follows the 1959 murders of four family members of the Clutter family in a small farming community located in Kansas. e non ction novel garnered a lot of popularity for the true crime genre, reaching a wider American audience. It wasn’t until the late 2000’s that the introduction of true crime entered an even broader platform, podcasts. e rst ever podcast that hypnotizes its audience to continually listen to gruesome crimes is “Serial”, a spino of the public radio show “ is American Life”. “Serial” is an investigative journalism podcast that narrates a non ction story over multiple episodes. It won a Peabody Award in 2015 and remains the fastest podcast to reach over 5 million downloads. Now, it seems as though everyone and their moth-

By Anna Roweer has a favorite true crime podcast, and there are loads of them to choose from. From “Dateline” to “Crime Junkie”, listeners can learn about the immoral acts of serial killers, stalkers, and outcasts. Each episode uncovers the psychological horrors of an individual who decided to take another person’s life. Something that was once unfathomable to hear about, has turned into a casual listening during a Friday afternoon stroll.

It is only natural to want to solve a problem, and true crime provides a suspenseful and exciting way to do that. Dean Fido, a psychologist at the University of Derby, describes our desire for crime as, “...we are always looking for something new and novel. Whether it’s good or bad, we need something that creates an element of excitement. When we mix this desire with insight and solving a puzzle, it can give us a short, sharp shock of adrenaline, but in a relatively safe environment”. We experience a range of emotions, from sadness for the victim, to anger, to fear of the killer. Many listen to crime as a safety net, a way to reconcile the fear of being in harm’s way. If someone knew all of the ways that people were attacked or victimized, then they can protect themselves from falling victim to that situation. But, like many podcasts emphasize, the victims never see it coming. Which begs the question, at what point does it become an attack on the victim rather than a tool to spread awareness of injustice?

Let me further explain this question. When you listen to a podcast, you learn about the victim or victims that su ered the horrors and brutality of the killing. Many podcasts go into detail about the motive, the murder itself, and share very personal aspects of the victim. Sometimes this is necessary to tell the story accurately, but other times, it may be more harmful than benecial. Are these episodes sanctioned by the families of the victim? Are they aware that these people are telling this story for the world to hear? Crime podcasts tether

between the line of ethical and unethical, sharing a story to bring about awareness for the victim, while smearing their secrets to the audience. ere are, of course, many cases that highlight the pure injustice of our legal system, ones that are shocking and unfair. Talking about cases such as those are vital to acknowledge the corruption of our legal system. ere are also instances where the families want the victim’s stories to be told. But, again, at what cost? Literally! Podcasters are making a pro t o of telling violent and grueling stories about real people, and more often than not, those people are not present to consent. How ethical is sharing true crime?

For many, listening isn’t enough. People want to see it happen, watch the crime unfold before their eyes. Crime documentaries provide the audience with rsthand accounts of some of the most horri c crimes to date. Most of the time, the documentary follows the victim’s story, often highlighting their testimony along with detectives who worked the case. In one documentary, “American Nightmare”, the victims of an unbelievable crime are heavily involved in the narration and production of the series. e documentary attacks the injustice that the victims faced, along with illuminating the strength and resilience of the victims. It’s purpose is clear, to give a platform for the victims to share their story, and expose the unfathomable experiences they had with not only the perpetrator, but law enforcement. However, there are instances where the victim isn’t involved, and the documentary does more harm than good.

Everyone at this point has heard the name Dahmer. Whether you remember when he rst wreaked havoc in the late 1900’s, or watched one of the many documentaries on him, he has quickly become one of the most infamous American serial killers. And with fame (good or bad) comes fascination. ere are at least 6 di erent movies detailing his disgusting and unthinkable crimes. e public, never having to go through

the terror of Dahmer, watch one of the many featured documentaries with popcorn in hand, treating it as just another must-watch, recommended by all of their friends for the twists and turns. However, what some fail to realize is how retraumatizing the making and remaking and re-remaking of Dahmer’s career in murder is to the surviving victims and their families. Imagine being able to live through one of the most horrifying experiences in your life, only to see the man’s face pop up on Net ix under the “Most Watched” category. It is impossible to hide from him. More often than not, the families of the victims are not asked for permission to release another version of Dahmer’s serial killings story, nor do they o er to share pro ts with them. Although this is only one instance of America glamorizing murder, it is not uncommon for Hollywood to monetize victim’s pain and su ering.

I must admit, I am an avid true crime listener. I follow closely as the narrator reveals who killed the next victim, ignorant that the story is real and not an episode of Law and Order. It’s di cult to even begin to grasp the unfortunate truth about each episode: that every name of a victim was someone’s mother, son, or friend. at it happened, and there are people who su er from it every single day. Will I stop listening? Probably not. But I am less ignorant towards my innocent fascination with crime. Listening while cooking dinner allows me to experience and learn from a horri c event without having to go through it myself. I listen to crime to prepare for the worst, but often forget that the “worst” that I am afraid of actually did happen to the victims of the story. Take into account how the story is being told, and who in the end is bene tting from sharing it. Next time you or I listen to a new episode, take a second to understand that it may be a story, but it’s someone’s story. Someone’s life.

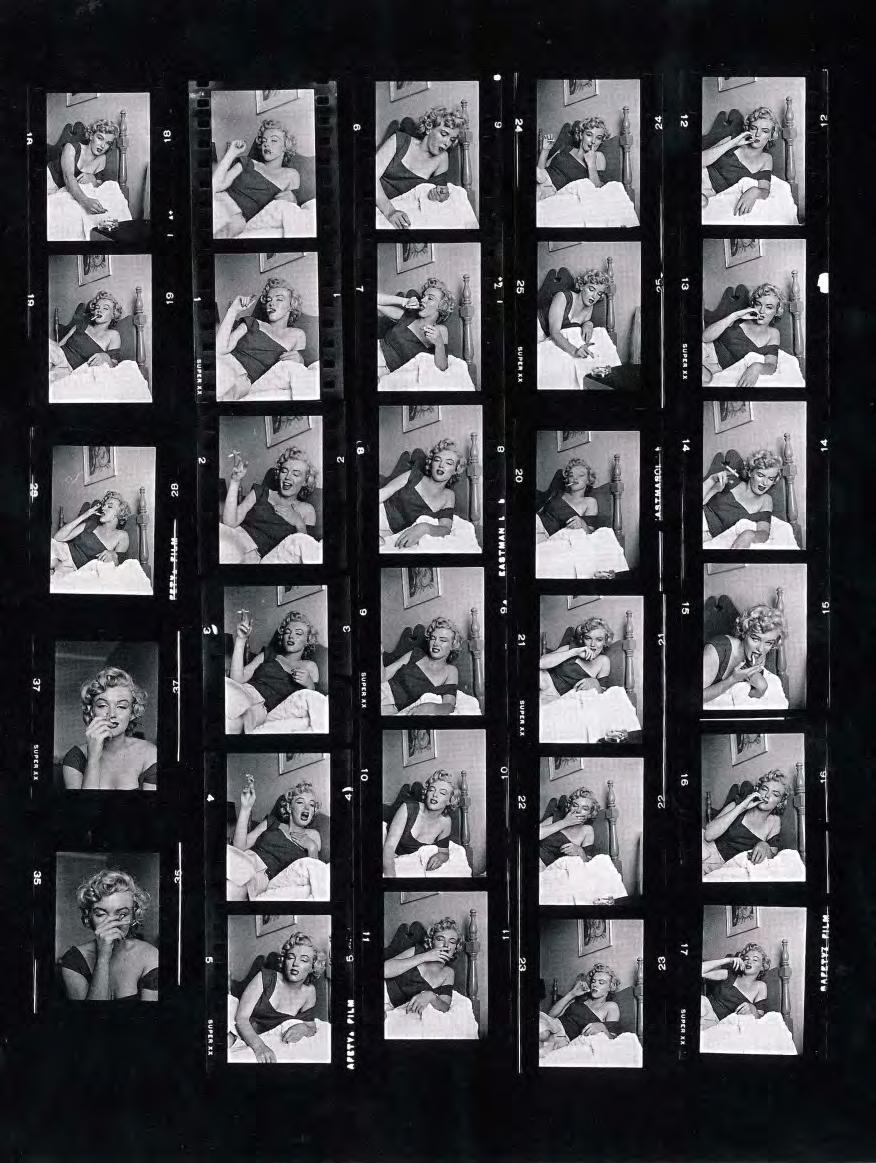

Oscar Wilde once said “Life imitates art far more than art imitates life”. This almost prophecy would not make itself more true than in the age of film noir.

Film noir is a style of movie making and cinematography most prevalent in the 40s and 50s. These movies were known for their dramatic lighting, thrilling plot lines, and unsavory characters.

By Caz Kopf

Film noir quite literally translates to “black cinema” and showed exactly that. It was a style of storytelling unlike anything seen before. The dark mood and pessimism displayed in these movies were new to audiences used to seeing comedies with Charlie Chaplin and romances like Gone with the Wind. The political and economic state of the country throughout the whole of the 30s and early 40s heavily impacted the rise of the film noir genre. Audiences were disheartened and disillusioned. The idea of the “American dream” no longer held any merit and people were tired. And as Oscar Wilde stated, life and art go hand in hand. The film noir movies being produced at the time

only seemed to reinforce the attitudes circulating the country all while delivering an exhilarating story at the same time.

Film noir movies are characterized by stories including detectives, crime, seedy bars, chain smoking cigarettes, and a mystery needing to be solved. The detective most likely is upset with the world for some reason or other. It could be he just got back from the war, his long time girlfriend broke his heart, or he’s just down on his luck. Whatever the reason, a shady dealing or gruesome crime needs to be solved. But he can’t solve it on his own. In walks the alluring, seductive femme fatale. She’s the missing piece to the puzzle and conveniently knows what to do next when the male characters are stuck.

Femme fatale, which translates to fatal woman, are characters that are gorgeous, striking, confident women who know what they want and go after it. Some even go so far as to take down the male character to achieve their motives all with a simple smile and a few flirtatious touches. Any man’s resolve is

easily broken down after meeting a femme fatale. These women want vengeance for the deeds done upon them and if somebody’s feelings have to get hurt? So what? This type of character was completely new to audiences, and they loved it. But she was actually just being reinvented for the times.

The idea of a woman getting revenge on her abuser or anybody who did her wrong can be traced back to ancient Greek and Mesopotamian mythology. In “The Odyssey”, Circe turns Odysseus’s men into pigs for invading her home. She did this even being Odysseus’s lover. Similarly, Ishtar, the goddess of war and love in Mesopotamian mythology, takes her revenge out on King Gilgamesh after he refuses her advances by creating the Bull of Heaven to kill him. The femme fatale has been leading men to their demise for millennia. Film noir just gave them a name.

Looking at any ranking of film noir movies online, The Maltese Falcon is sure to be on that list. It’s considered the first true film noir movie. The movie follows detective Samuel Spade and his investigation to discover who killed his partner, Miles Archer. This investigation leads to an even bigger mystery surrounding a priceless artifact, the Maltese Falcon. Sam gets caught up with shady characters willing to commit robbery, bribery, and murder to obtain it. Brigid O’Shaughnessy is one of these characters. Mary Astor who played Brigid was a controversial woman in real life as well. A few years before the movie was released, Astor was in a custody battle with her second husband which was being dutifully reported on by the media, and her notoriety even helped her to land the role.

Miss O’Shaughnessy is a woman in a man’s world trying to get by. She enlists the help of Samuel Spade after claiming her sister is caught up with a man named Floyd Thursby who whisked her away which was unacceptable for the time. Miles Archer is sent out to shadow Thursby which results in his death. Shortly thereafter, Thursby turns up dead as well. Sam is thought to have killed Thursby to avenge his partner making him all the more motivated to find out who really killed the pair. In comes

the mysterious Brigid O’Shaughnessy. Sam doesn’t trust her from the start which ends up being his saving grace because it was Miss O’Shaughnessy who killed them. She killed Archer to frame Thurby, and then killed Thursby to avoid sharing the profit from the Falcon. Miss O’Shaughnessy is a liar and confesses to her lies. She has no qualms about making somebody else take the blame, nor does she feel any guilt for using Sam’s love work in her favor. She was one of the first women in media who was a complex character. She did more than just take care of the kids and have dinner ready for her husband. Women were drawn to her for her deceit, and men were drawn to her for her looks. Everybody in the audience loved her for something.

Perhaps that’s why the femme fatale was and still is so popular. The femme fatale is a woman who is not afraid of anything. She is comfortable in normally uncomfortable settings. Settings where women “aren’t” supposed to be. Women started seeing themselves in other roles than housewives. But on the flip side, they were still disrespected and sexualized in these new roles.

Throughout the entirety of The Maltese Falcon, Miss O’Shaughnessy is addressed with pet names. “Precious”, “darling”, “good girl”, and others. These names degrade her and reveal the men in the movie regard her as a child playing dress up in a man’s world. Who cares that she killed two people for her own selfish gain? She’s a woman, so she couldn’t possibly join the men in the big leagues. And Miss O’Shaughnessy has the worst ending. She goes to jail for her two murders while Joel Cairo who held Sam at gunpoint and Mr. Gutman, who bribes and cheats his way to the Falcon, goes free to continue searching for the elusive Falcon.

The modern day femme fatale is starting to show women can be both good and bad and a myriad of other characteristics. Natasha Romanoff, aka Black Widow in the Marvel universe, is a classic example of a stereotypical femme fatale who eventually becomes a fleshed out character. Upon her first appearance in Iron Man 2, Natasha is an ass-kicking

woman in tights and a full face of makeup. As the years went on, Marvel expanded, and Natasha’s appearances became more frequent even having her own movie, she grew into more than just a seductress. She cares about her team, ethics, and outsmarting her enemies using more than just her looks. Another example is Lorraine Broughton in the 2017 film Atomic Blonde. The movie follows spy Lorraine as she tracks down double agents in 1989. She seduces men in nightclubs only to kill them when they are alone. This movie even goes so far to flip the femme fatale stereotype by having a scene where Lorraine seduces a woman. Not only is modern media making women more than just a “good girl” but also breaking out of the heteronormativity of old school Hollywood.

Who knows where the film industry will go with the future femme fatales but if recent films are anything to go by, female characters are going to be more than just a pretty face at the whim of a man.

Every Friday since January 5th, my friends and I have sat on the couch for 2 hours and watched the airing episode of season 16 RuPaul’s Drag Race. This season is campy, consists of fashion and drama, and full of insane talent; but drag hasn’t always been just glitz and glamor.

The performance of gender expression dates can be traced all the way back to 700 BC, where in ancient Greek plays men cross-dressed as women, since women were not allowed to participate in theater. This practice continued all the way into the late 1500s to 1600s with English Renaissance Theatre performing plays such as Twelfth Night that would have male cross dressers playing Viola and Olivia. The “drag” terminology can generally be traced back to Shakespeare’s plays. Where when male actors would perform as women and wear long costume dresses; those dresses would “drag” across the stage floor. Another early form of drag was present in Japan, in the early 18th century. Kabuki, a classical form of Japanese theater, consisted of dance-drama, including performances featuring female impersonators. These performers would showcase intricate makeup, falsetto voices, and feminine dances. This was similar to Baroque operas when in the mid 1700s, the Catholic church in Italy banned women from appearing on any Italian stage, so men had to learn how to sing in falsetto and perform effeminately. These early representations of gender performance are evidence that the art of drag

has been embedded across time and culture. However, the modern drag tradition, as we understand it, began to emerge later in history.

The term “drag queen” first emerged in a subset of queer-coded English slang in the late 19th century, also known as Polari. The secret language born out of the criminalization of the LGBT+ community in England, when it was used to describe men appearing in women’s clothing in the theater community. By the 1920’s, “drag” was knowingly and widely being used by gay people, but the first known use of the word was in 1870. The grand debut of “drag” can also be traced to 1860s England, when Ernest Boulton of the duo Boulton and Park described his cross-dressing act as drag. Thomas Ernest Boulton and Frederick William Park, also known as Fanny and Stella, were Victorian-style crossdressers who got arrested in 1870 for leaving the theater in drag. They were both held in prison for two months. During the hearings Reynolds’s Newspaper, a popular paper in the UK at that time, reported that a witness said, “We shall come in drag,” meaning they would appear at the hearing in women’s clothing. This is the first known published use of the term “drag” for queer cross-dressing. However, it is important to mention that around the 1860s in the United States the drag tradition had roots in racism. Female impersonators were performing

in minstrel shows. During these shows white male actors wore blackface to portray black women. Drag has a very complex history and is done and performed differently by everyone.

A prominent figure when discussing drag inthe late 1800s is William Dorsey Swann, the first queen of drag! William Dorsey Swann was born enslaved in 1858 in Maryland. After he was freed Swann lived a life dedicated to LGBTQ+ activism. He began to host drag balls as early as 1882. Drag balls at this time were mainly parties where men could attend dressed as women, women could attend dressed as men and where gay men could dance with each other. The first recorded drag ball occurred in 1869, but they gained popularity in the 1880s, especially with Swann’s help. Most of Swann’s balls consisted of formerly enslaved men who gathered to dance in formal gowns. Swann and his attendees performed dances such as the cakewalk, which was a dance created by enslaved people that mocked the mannerisms of plantation owners. This resistance dance consisted of movements and offbeat ‘oomph’ rhythm evolved to resemble voguing, a popular dance style popularized in the 1960s Harlem’s queer ball scene. In 1888, during one of Swann’s drag balls, there was a police raid on his

home. A report of the raid was posted in the Washington Post in April 1888, and spotlighted Swann, “who was arrayed in a gorgeous dress of cream-colored satin.” Swann tried to prevent the police from entering, allowing a few guests to escape before he was arrested. The National Archive, while undergoing the project of rediscovering black history, recovered a case file mentioning William D. Swan. The federal record reveals Swann making queer history, since the file displays the first instance where an “American [took] specific legal and political steps to defend the queer community’s right to gather without the threat of criminalization, suppression, or police violence.” William Dorsey Swann was the first in person in history to describe himself as a “queen of drag,” a precursor to the modern drag queen. As a black gay man, Swann paved the way for future drag queens and gay men of color.

By the early 1900s, drag shifted from a performance of actors to an individual form of entertainment. This shift emphasized a new spectacle of entertainment of what is known as “Vaudeville”. Vaudeville deepened the connection between drag and gay culture. This theatrical genre combined female impersonation with burlesque; it also fused with new versions of comedy, music, and dancing. Vaudeville drag performances paved the way for gender-bending theater that spread into the 1920s. It was through Vaudeville performances that another drag queen came to fame, Julian Eltinge. Julian Eltinge began performing as a female impersonator at age 10 and starred in shows from 1910-1930, when unfortunately the police began to take strong action against people in public drag. Another shift occurred in the 1930s with Vaudeville going out of the theater and into nightclubs. Also between 1920-1933 the Unit-

ed States entered the Prohibition era, which abolished alcohol production and consumption. This led to gay people and drag performers using newly created underground clubs as an opportunity to express themselves. These secret spaces offered an underground utopia for American gay men and women. However, this didn’t last long. As drag gained popularity, the safe spaces began to be hunted down by the police. Female impersonation was completely banned in New York, one of the drag havens in the US, in 1935 putting an end to Vaudeville performances.

Fast forward to the 1950s and 1960s, World War II reinstilled the heteronormative culture and beliefs that fought against the acceptance of drag and queer culture. Throughout these years the LGBTQ+ community fought back, most notably Drag queens, including the acclaimed Marsha P. Johnson who protested police raids on homosexual clubs in New York City during the Stonewall Riot of 1969. Drag continued to suffer up until the 70s, when the hub of queer culture expanded

to San Francisco, and a new way of drag took over. Drag returned to parts of New York in the 1970s, especially Harlem, and some of the biggest drag balls were organized there. Drag was gaining popularity all over the states, especially in pop culture, with the Cockettes. The Cockettes were a multiracial and gender fluid drag group from San Francisco who performed lavish and wild productions that included chorus lines. Alongside the Cockettes, John Waters began releasing transgressive films that included aspects of queer culture. The film Pink Flamingos, even starred the iconic drag queen Divine. Even though drag was beginning to be more widely embraced, much of drag culture remained rooted in underground scenes.

Drag continued to be captured on screen with the 1990 Paris Is Burning, directed by Jennie Livingston, which made drag mainstream. Drag culture seen in the 80s was now a lot more visible to the public. The documentary paved the way in giving voice to a community of people that had long been hidden in popular media. Paris Is Burning hones in on New York City’s Black and Latinx Harlem drag-ball scene. The film was made over a course of seven years and intimately offers insight into the extravagant fashion contests taking place between rival fashion “houses.” The fashion houses eventually evolve into today’s drag families. The 1980s were a time of rampant homophobia and racism, brought on by the AIDS crisis. Within the drag culture that emerged however, the LGBTQ+ community, especially Black and Latinx individuals, found refuge and expression in the drag-ball scene. One of these people was the queen we all know and love, RuPaul!

In the late 1980s going into the early 1990s, RuPaul worked the club scene in Georgia. During this time, RuPaul was still performing in a kind of drag known as genderfuck. Her appearance generally consisted of feminine makeup and clothes, but no padding or taping to make the body look female. She co-produced and starred in an low-budget underground film series called Starbooty in 1987, where she was in genderfuck. RuPaul’s first prominent national

exposure came later in 1989, when she was featured in the “Love Shack” music video by The B-52’s. The 1990s were a quick rise to fame for the queen of all queens. In 1993, RuPaul released her hit song, “Supermodel,” which quickly rose to number two on Billboard’s Hot Dance Music/Club Play chart; she now has 15 thriving albums out. She began performing at several New York City nightclubs, one where she met the famed Michelle Visage, and also began performing at the annual Wigstock drag festival. In 1996 RuPaul began hosting her own talk show on VH1, called The RuPaul Show. She interviewed celebrity guests and performed music and comedy skits with Visage as her co-host. Then in 2009 the world stopped when the now hit show RuPaul’s Drag Race premiered. On the show drag queens competed in music, fashion, and acting challenges to be selected by RuPaul as America’s next drag superstar. The show has greatly changed over time, when the series premiered, the aim was to show the female illusion done by cisgender gay men. This completely ignored the reality that trans women had been doing drag alongside these men. The franchise did evolve to now have a wider LGBTQ+ representation and today some of the greatest queens that have appeared on drag race are proud trans or nonbinary individuals. Along with the show, RuPaul’s DragCon also started taking place, it is the largest drag convention in the world. RuPaul’s Drag Race has won 29 Emmy Awards and the art of drag is more universal than ever before.

Today, the 16th season of Rupaul is airing and bringing us a new set of ultra talented queens. The evolution of drag has brought about a new love for the art with drag shows in every city, queens performing concerts and broadway shows, and conventions with rising queens competing for fame. Current drag ranges from dressing up to wearing intricate and colorful makeup, gender crossing or performing a persona; but drag will always have its roots in queer culture. While today’s drag brings nothing but joy and comfort, drag is often subject to political controversies and opinions that are seeped in unjust fear. Dragphobia is an extension of the United State’s shameful history of homophobia and transphobia, and a lot of the anti-drag rhetoric used today was started by conservative lawmakers. They use this hate speech and target primarily “Drag Queen Story Hours,” which

are family-friendly events where drag queens dress in fun costumes and read books to children. The books read often have themes of diversity and acceptance. Policing gender isn’t new for this country and the laws put in place trying to stop the public appearances of drag are simply the latest attack on the LGBTQ+ community. As RuPaul said at the 2024 Emmy’s, “If a drag queen wants to read you a story at a library, listen to her.” Drag allows people to play with gender roles; it can be a way to explore and challenge societal norms surrounding gender and create beautiful queer art through performance. Drag is ever-evolving and has absolved boundaries, making it a place of comfort and expression for people who do not fit into the rigid binary. If you want to get a taste of gender-bending drag in person, Sasha Velour is coming to Charleston for the Spoleto Festival in June and the world of Charleston drag is always ready to be explored.

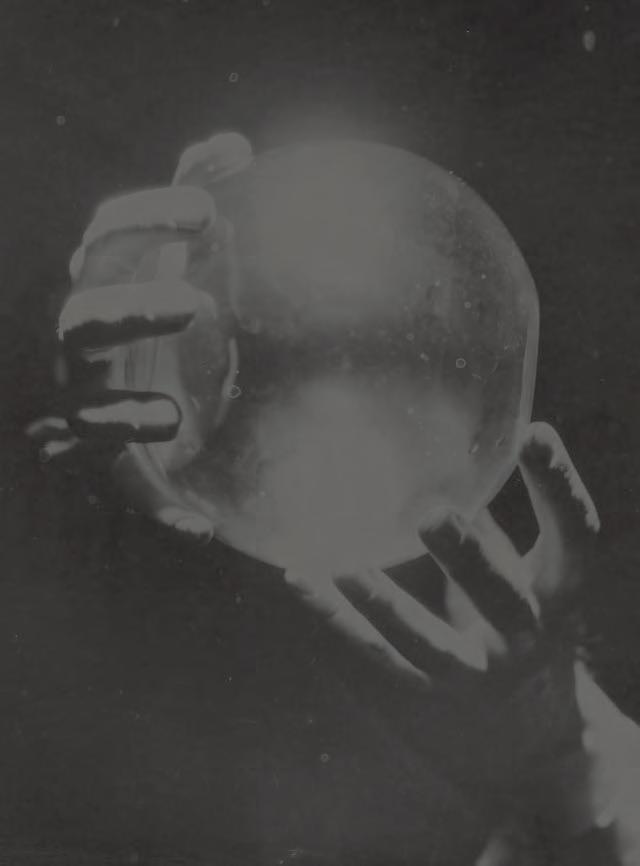

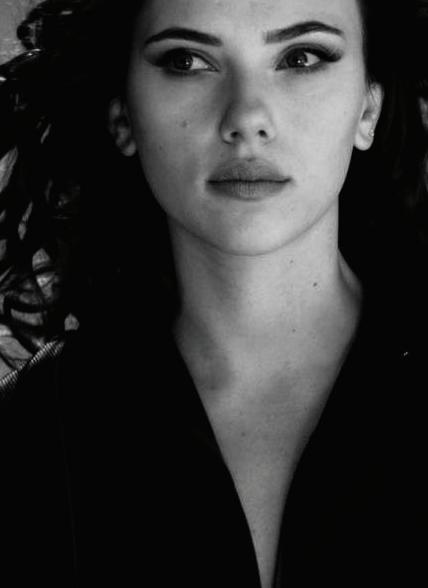

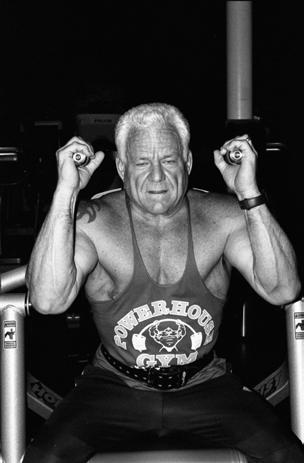

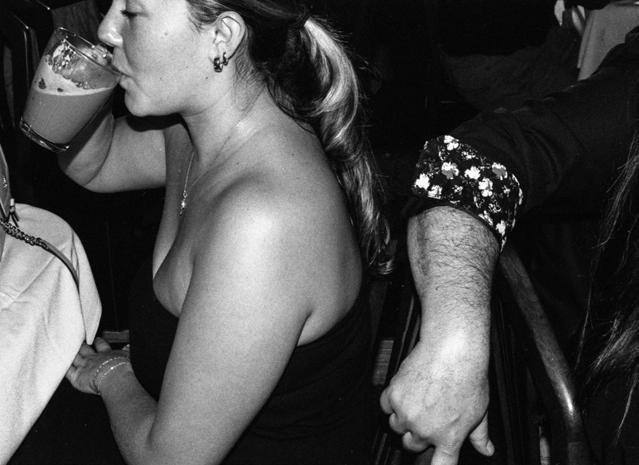

On the next two pages, take these images and add them to your own scrapebook, journal, or anything you want.

Be Creati ve. Make these images your own.

Marina Silvestri

Marina Silvestri

ciao! until next time...