20 minute read

HEMP

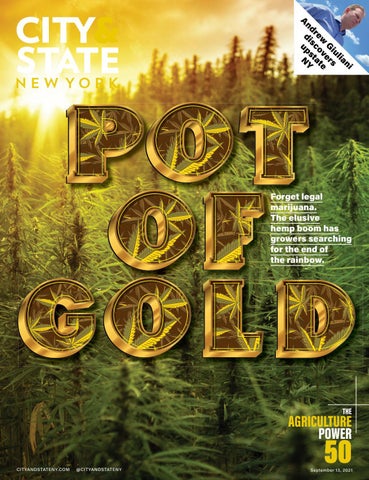

IN CASE YOU missed the parades featuring giant doobie floats, the joint giveaways for the vaccinated or the general celebratory aroma of city streets, recreational marijuana is now legal in New York. While attention is trained on the new legal drug business the state is building, another even larger cannabis business is awaiting its day in the sun. Already legal to grow and process, industrial hemp is the potentially billion-dollar New York industry few are paying attention to yet. While it may take longer to scale up than recreational marijuana, industrial hemp could have even greater economic potential for the state.

Although most people are familiar with the drug marijuana that comes from the cannabis plant, far fewer know about the many uses for hemp, which looks similar, but has negligible amounts of the psychoactive chemical THC. For those who are familiar with hemp, they may most closely associate it with their local hippie stores next to the crystals and incense. But its uses range from textiles for clothes to construction material to food. “People are chasing these bright shiny objects, and I think those will have maybe short-lived potential,” said Daniel Dolgin, owner of

Advertisement

Eaton Hemp in Central New York, of recreational marijuana. “I think there will be more losers than winners – there will be big winners, but the industrial side has much less sex appeal.” As companies seek green alternatives to traditional products from cotton (which is incredibly water-intensive to grow and process) to plastics, hemp is becoming increasingly popular.

But it still must overcome a decadeslong disinformation campaign associating it with its closely related drug cousin, and set up the supply chains to compete with the major industries that helped to kill hemp in the first place.

Dolgin’s farm was one of the first to win a license under the state Department of Agriculture and Markets’ Industrial Hemp Agricultural Research Pilot Program established in 2015. Since then, he’s been growing his vertically integrated business – growing, processing, creating and marketing hemp products – as a sort of proof of concept to others interested in the industry. “We’re in sort of the innovation stage where you have to show like, hey, this can be done,” Dolgin said. Currently, Eaton Hemp has entered the pet care industry with a popular hemp pet bedding, among other products including hemp-based foods. The major roadblock now is getting other farmers interested in

HemphypeA new industry is budding in New York. It could be transformative, or a lost chance.

EATON HEMP Daniel Dolgin is one of New York’s first licensed hemp growers. He calls this the crop’s “innovation stage.”

Hemphype By Rebecca C. Lewis

taking the potential risk, as well as getting investors and companies to buy into the industry, which takes time.

EATON HEMP ALSO sells CBD products, which are made from a hemp extract that for a brief moment completely dominated the hemp market. It’s not a drug per se, but it’s touted as offering a calming effect without the high of THC. Unlike with other industrial hemp uses that require a degree of risk in building up the market, CBD was a popular fad seen as an easy market to enter. The problem was that the market became oversaturated with products without proper regulations. Southern Tier Assembly Member Donna Lupardo, sponsor of various hemp bills, said that while she’s eager to get those CBD regulations finalized, the state is ripe to capitalize on hemp’s many other uses. “I have a briefcase – I call it my hemp sample bag,” Lupardo said of a briefcase made of hemp fibers that she uses to carry sample hemp products like alternative Styrofoam and building materials. “Once people see what’s possible, they’re very intrigued by it.”

New York is already in a good position to enter the slowly burgeoning industrial hemp market as a major national leader. “We’re already considered a leader in this industry,” Lupardo said, adding that the state was among the top five in the country in terms of licensed acreage before the pandemic. “We are absolutely viewed as not only innovators in terms of new products and new potential, we’re also viewed as a state that’s willing to push the envelope.” Daniel Walcyzk is a professor of mechanical engineering at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute focused on hemp biocomposites as an alternative to the likes of carbon fiber. He said that he can think of no state that is more advanced in its research. “New York has the potential to be a key leader in bast fiber – including hemp – research, and development and application,” Walcyzk said. “There just needs to be more thought into where the funding is going to go.”

From an agricultural standpoint, New York is well-suited for growing hemp, which thrives in a temperate climate like the state’s, unlike cannabis for recreational marijuana, which does better in warmer climes. It is not water intensive; it helps replenish soil when used as part of a regular crop rotation (and can even be used for remediating brownfields with toxic or hazardous materials in the soil); and generally does not require pesticides or herbicides to grow as it naturally suppresses weeds. Also, it offers a high return on energy consumed to grow the plant as effectively every part can be used in some way. “Our motto is nothing goes to waste, because we use every part of the plant to create a viable product,” Dolgin said.

Certainly, the state is better suited for growing industrial hemp than recreational marijuana, most of which will likely be grown in energy-intensive indoor grow operations in New York. Jennifer Gilbert Jenkins, an associate professor of agricultural science at SUNY Morrisville, said that the state’s geography also is conducive to a robust industrial hemp industry as it has agricultural regions interspersed with small urban areas. “This means that materials don’t have to travel far to get from farm gate to the first

Hemp grows well in New York, where many farmers have licensed land to cultivate it.

stage of processing,” Gilbert Jenkins said. “The geography of the state lends itself to ease of tying agricultural and industrial sectors together.”

In that vein, the agricultural side is just one part of the industry that could potentially benefit New York, with the processing and manufacturing side presenting a potential boon for the state as well. Gilbert Jenkins pointed out that the growth of the hemp industry could help revitalize rural areas that have lost manufacturing jobs in the past several decades if major industries decide to move into the state to process the raw materials they purchase. “That’s the million-dollar question,” Gilbert Jenkins said when asked just how big this industry could be for New York. “I think it could be a great tool to use to revitalize downtrodden poorer areas of the state hurting for investment and job growth.” Hemp also offers New York an avenue into the green jobs sector as more companies are looking to invest in environmental alternatives to traditional products. Much stock has been put into the prospect of solar panel manufacturing plants in the state, but hemp growing and processing is another way to grow the sector. Hemp could be a multibillion-dollar industry, particularly in the construction field, said Walcyzk. But it’s more than that. “It could be huge, but I think more importantly is that it’s the future,” Walczyk said. “Oil is going to run out, natural gas is going to run out – and carbon fiber, by the way, is petroleum based. … (Hemp) materials have to be part of the engineering material future.”

DESPITE THE MULTIFACETED nature of industrial hemp, the state still has major roadblocks to overcome. First and foremost are the decades of disinformation about the plant after it was lumped in with the drug marijuana that depressed its use and research for years. Hemp was at one point a major crop in the U.S., to the point that colonial farmers were required to grow it. In the 19th century, Henry Ford famously created blueprints for a car built out of hemp biocomposites. In fact, in an article written in 1937, one magazine said that hemp was poised to become “the billion-dollar crop.”

But in the 1930s and later with the Nixon era and the Rockefeller drug laws, hemp got lumped together with marijuana as part of a concerted lobbying effort by major industries that stood to lose if hemp became too big, including petroleum (the producer of synthetic materials), cotton and paper. In fact, strict laws about and demonization of marijuana have been traced back to the attempt to kill the hemp industry when new inventions made processing it easier and cheaper than before. It wasn’t until the 2014 U.S. Farm Bill that hemp became legal to grow for research purposes and was given a definition to differentiate it from marijuana. So the state has a long education campaign ahead of it to undo years of intentional effort to keep the hemp industry from burgeoning, even as attitudes change.

There is also the issue of getting investors interested in the industry, companies to set up shop or source from New York and support from the state. “There’s no real way that farmers on our own can just create this industry through entrepreneurship and grit and hustle,” said Damian Fagon, owner of Gullybean farm in the Hudson Valley. “It has to kind of come from the top down with some guidance from the state.” Lupardo is working on her end to get buy-in from the state through conversations with Empire State Development, but she said that the pandemic has interrupted her efforts.

Dolgin said he has had conversations with the state Department of Transportation and the Executive Chamber about using hemp for phytoremediation – remediating land with toxins – and erosion control, but he also acknowledged the hurdles the state still needs to overcome. He compared the industry to different stages of development for the advent of the internet. “Right now, a lot of people who are kind of looking at the industry are looking at internet 3.0 and looking at uses for industrial hemp that don’t have a market, don’t have the technology, don’t have the efficiency, but it all holds a lot of promise,” Dolgin said. It’s why he says his company is thinking about “internet 1.0” by finding industries they can add products to for which there is already demand and buying hemp from other farmers to encourage them to begin growing it themselves.

Fagon also cautioned against pinning too much hope on the promise of industrial hemp in New York once the market begins to take off more and other states start to get involved in growing, manufacturing and processing. He said that while hemp textiles could help revitalize the likes of garment-making in New York City, he said that competing with other states with more farmland and infrastructure could put a damper on industrial hemp in New York. “Industrial hemp will be subject to the same push and pull factors that pushed the dairy industry out of New York,” Fagon said. He doesn’t want to see farmers fall into the same trap as with CBD, which promised big payouts but turned into a bust for many.

But many hemp proponents see a real opportunity for New York to enter the industry in a big way. And with a new governor in the Executive Mansion, they have renewed hope. “We have a governor who’s not afraid to have her picture taken with me standing next to a cannabis plant,” Lupardo said, recalling a 2017 picture then-Lt. Gov. Kathy Hochul asked to have taken at the state’s first industrial hemp summit. “She’s very, very, very big on what we’re talking about right here.” ■

On the farm with Andrew Giuliani

The long shot Republican candidate for governor is taking his message of MAGA cliches straight to the people.

By Zach Williams

On the day state Attorney General Letitia James released the report that ended Andrew Cuomo’s career, Andrew Giuliani was talking to upstaters at Empire Farm Days.

ZACH WILLIAMS A NDREW GIULIANI IS easy to spot in the crowd at Empire Farm Days. The Republican candidate for governor is the only guy wearing casual knit sneakers and Jacob Cohën slacks at the largest agricultural trade show in the Northeast. He leaves no doubt about where he comes from every time he shakes a hand or slaps a back. “I’m out of Manhattan,” he tells one after another. “I’m one of those downstaters, but that’s OK.” He might not know much about the nuts and bolts of combines, or recognize the name of the local member of the Assembly, but the 35-year-old son of former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani can relate in another way to the types of conservative voters he needs to win the GOP nomination next June.

It starts with the name. While Rudy Giuliani might be a target of scorn on the political left nowadays because of his association with former President Donald Trump and their joint efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election, the former mayor had plenty of fans among the people who talked to his son at Empire Farm Days. “He’s just a stand-up guy,” Bruce Reeves, a farmer from Baldwinsville, said about the former mayor in an interview. Andrew Giuliani then shifts the conversation to the “defund the police movement” and “Second Amendment rights.” Reeves had not heard of any other GOP candidates for governor and he likes what he hears from Andrew Giuliani. “What do we got to lose?” he says of electing the millennial son of Rudy.

Appearances at events like Empire Farm Days are Giuliani’s way of overcoming some big disadvantages in his long shot campaign for governor. He cannot compete with Rep. Lee Zeldin in fundraising or endorsements, but Giuliani has a famous name, hustle and command of the culture war clichés that could appeal to GOP primary voters. That might not be enough to get him elected as the first Republican governor in two decades, but it could go a long way toward changing the public’s perceptions of him.

He used to be best known for loudly repeating his father’s words at Rudy’s 1994 inauguration as mayor, which was lampooned by comedian Chris Farley in a “Saturday Night Live” skit. Andrew attracted additional attention as an undergrad at Duke University after several incidents led to him being kicked off the golf team. He then sued the school claiming he was guaranteed a spot on the team and lifetime access to the Duke golf facilities, but the suit was later tossed. His appointment years later as a White House aide during the Trump administration – which included a lot of time hitting the links with the president – only added to his reputation as a lifelong beneficiary of nepotism. Rivals like Zeldin of Long Island – the front-runner for the GOP nomination for governor – and former Westchester County Executive Rob Astorino have experience as elected officials and connections to the state party, but Giuliani touts something else. “I’m a politician out of the womb,” he told reporters while announcing his campaign in lower Manhattan in May. “It’s in my DNA.” His suspect claim of being the most experienced candidate in the race with “parts of 32 years in politics and government” and “parts of five decades in politics” inspired a fresh round of mockery in the media.

His candidacy has not fared much better since when it comes to the mainstream media.

He got burned at a Schenectady bakery after staging a campaign event there uninvited. “If I were going to host a political candidate, it wouldn’t be Andrew Giuliani. It would be someone with more traction, to put it diplomatically,” the owner told The Daily Gazette. “I’m at a loss here.” New York magazine wrote about how his campaign was less about politics and more about dealing with lingering issues following his parents’ public divorce. Father and son were estranged for years, though they eventually smoothed things over in time for Rudy’s political influence to power Andrew’s rise in right-wing circles. “(The author) pushed a narrative and it is what it is,” Giuliani said of the magazine story.

Andrew Giuliani’s campaign was dealt a big blow when he did not get a single vote from party insiders at a gathering in June where they deemed Zeldin their preferred choice. That fact alone highlights the limits of his father’s name and helps explain why an Upper East Side native is appealing to voters directly by attending events like the Lewis County Fair and Empire Farm Days while making appearances on right-wing media outlets. “It’s just a matter of going and meet-

Giuliani talked up his connections to former President Donald Trump, though Trump hasn’t returned the favor.

ing as many voters as possible,” Giuliani says following an impromptu appearance on Newsmax – where he was briefly a paid contributor – minutes after the release of the damning report by state Attorney General Letitia James on sexual harassment allegations against Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

The report gives Giuliani a chance to hate on the Democrats while grandstanding with potential voters. “Do you think Tish James is going to run?” Monica Cody of Cazenovia asks him after he approaches a table where she is sitting with her husband Bill Cody and their children. “You know what? Good question,” Giuliani responds. “We were just talking about it. I think there’s a good chance that she does. I think there is a good chance that she does.” He explains how the state Senate could convict the embattled governor if he were to get impeached. Bill and Monica Cody are no fans of Cuomo, but they have some questions about who might replace him:

“Giuliani, he’s definitely running?” Monica Cody asks.

“Yeah, that’s me, so I’m running,” Giuliani replies.

“No, I’m Andrew. I’m his son,” Giuliani replies.

“You’re running? Not your dad,” Monica Cody asks.

“No. He’s not running. I’m running,” Giuliani responds.

“Well good luck. You know who else is running?” Monica Cody adds.

Giuliani explains that there is a guy named Zeldin and a guy named Astorino – but he says he is the guy to beat based on a poll his campaign released weeks before that showed him with an 8-point lead on Zeldin. “You get my vote!” someone yells from a nearby table as Giuliani goes on about how he is going to stop the “AOCs of the world” from hurting the good people of upstate New York. Monica Cody asks where he stands on the use of agricultural land for green energy. Giuliani responds with a long-winded answer. “There’s nothing that actually we can implement as a way to actually take over what’s happened, let’s say downstate at Indian Point or as a way where we can do clean fracking, let’s say on the Southern Tier over here,” he says. “We’ve just seen this kind of quick rush to green energy and renewables without actually saying: ‘Well, can the grid actually handle it yet?’ It can’t handle it yet. So it’s not actually in a place right now where we actually can power our state with.” That was not exactly what the Codys were getting at.

“What about 94C landowner property rights?” Monica Cody asks. Giuliani asks for an explanation. Bill Cody explains that 94C is a controversial state law that streamlines the process for locating renewable energy projects in places like Central New York. This drives up demand for agricultural land and places limits on zoning laws imposed by local governments. Giuliani pivots back to a key campaign talking point. “This has happened on so many different issues – not just energy, not just agriculture – where you continue to see the Cuomo administration centralize power in Albany and all that,” he says. “Yeah,” replies Bill Cody, but his wife still has doubts that Giuliani is up to the task of protecting upstate farmland. “My concern is that anybody that’s (dealing) with the Legislature has to be well informed,” she says in an interview. Still, they say they are willing to give Giuliani a chance in the absence of other attractive candidates. They have never heard of Zeldin, and Bill Cody says Astorino – who lost the 2014 gubernatorial election to Cuomo – is too “weak” to challenge the forces of liberalism run amok.

Opposition to Democrats is a theme that Giuliani returns to at Empire Farm Days. The political left will defund the police while he will “back the blue” and allow them to do their jobs as they see fit. “Stop, question and frisk worked in the ’90s in New York City,” he says in an interview. “It’s not as dangerous as it was 35 years ago, but we see crime going up.” He also harps on the dangers of critical race theory, though he strug-

– R.J. Windhausen, homebuilder

gled to define exactly what that term means. “The theory is this original sin in the United States of America that we cannot recover from,” he adds. “We are continually divided on racial lines, on religious lines, it’s kind of a continued push of that.” Giuliani does not differ much from Zeldin and other Republicans when it comes to identifying what they say is wrong with Democrats, but he has a knack for putting it in uniquely personal terms. “(Cuomo) described himself as Italian (while) grabbing people,” he tells One America News Network during a late afternoon appearance from the hill overlooking Empire Farm Days. “As an Italian, I’m offended that he would actually even say that, and group us in like that. That’s beyond disgusting.” Then it’s back to bashing the Democrats with voters in person at a tractor pull down the road.

The Manhattanite is no expert on the rural sport of measuring how far a turbocharged tractor can drag a weighted sled down a dirt track, but Giuliani does know a thing or two about appealing to the types of people who will pay $20 on a Tuesday night to watch their favorite drivers compete. Giuliani is sipping a spiked seltzer and introducing himself to as many people as he can amid the cacophony of screaming engines and billowing smoke. Many of them have never heard of him, but they get an idea of what he stands for as soon as they hear his last name. “This is all grassroots people,” homebuilder R.J. Windhausen explains. “I can tell you right now there ain’t 10 of them up here that want anything more than Trump.” The former president has not expressed any public willingness to endorse his former golf partner despite Giuliani’s efforts to talk up their connection, but the long shot candidate for governor may not need it if everything goes well for him on the campaign trail.

His family name gives him an in with voters at a time when he is pushing hard to be taken seriously as a candidate. He cannot offer voters policy nuance or the benefit of much political experience except for a few years as a liaison to sports teams and small businesses as a White House aide. Party elites have already gotten behind Zeldin. However, long shot candidates have staged upsets before in Republican primaries. Businessman Carl Paladino beat former Rep. Rick Lazio to become the 2010 GOP gubernatorial nominee despite his lack of institutional support. Giuliani has reported having just a few hundred thousand dollars to compete against Zeldin, who has amassed a multimillion-dollar war chest for the primary.

Giuliani has also had to adjust his campaign messaging since Cuomo’s resignation by joining other Republicans in labeling his successor, Gov. Kathy Hochul, as just another out-of-touch Democrat who is pushing supposedly unconstitutional vaccine and mask mandates on law-abiding New Yorkers. The boos a Giuliani sign got at a recent baseball game at CitiField, and the unflattering headlines it generated, highlight his ongoing struggles in being taken seriously, but Republican voters see him differently – at least judging by the reception he got at Empire Farm Days. “I said to my wife, ‘Hmm, that’s Rudy’s boy right there,” Windhausen said in an interview. “He introduced himself and I’m not into politics but I’ll listen and see what he has to say.” ■