6 minute read

In Focus

Project Zero Cultivating a culture of creativityHeroes

Anew type of learning has entered Grandview Heights Schools, and it’s changing minds and challenging the status quo.

Project Zero, a research center at the Harvard University Graduate School of Education, promotes new ways of thinking about intelligence, creativity and understanding. According to the Project Zero website, its aim is to “understand and enhance learning, thinking and creativity for individuals and groups in the arts and other disciplines.” In other words, it offers an entirely new way of learning – a way that empowers students.

Through seminars, book studies and courses, teachers in Project Zero use Harvard research to implement new educational practices in their classroom. The program offers tools in multiple different subjects and areas, but the underlying mission through it all is to help students think for themselves rather than just memorize facts.

Marc Alter, the director of 21st century learning for Grandview Heights Schools, began an unofficial Project Zero program in Upper Arlington before introducing it to Grandview five years ago.

Project Zero workshops demonstrate the research center’s findings and offer tools for teachers to implement in their classrooms. Alter says the practices Project Zero encourages include visualizing the process of thinking, documenting learning and fostering an environment of creativity.

“It really supports the idea of students gaining ownership of their learning, having a better understanding of their learning and being advocates for their learning,” Alter says.

Alter began by creating inquiry groups for teachers to study books following Project Zero’s ideas, including Creating Cultures of Thinking by Ron Ritchhart.

Through Project Zero, teachers also have the option to attend workshops and professional development days around central Ohio that relate to Project Zero. Events have been hosted by authors and organizations such as the Columbus Museum of Art.

If teachers need additional assistance in implementing Project Zero’s tools in the classroom, Alter works with them for as long as they need, anywhere from a few

Staff engage in professional development using Project Zero philosophies and techniques.

hours to a whole week. He offers one-on-one brainstorming sessions as well as co-taught classes.

“One of my goals is always giving the kids and teachers a space to slow down, think and be reflective,” says Alter, “because we have to bounce from one thing to the other all day long in school or in life.”

Alter helped a French teacher set up a visual flowchart project on Francophone culture. Students chose a topic then brainstormed subtopics visually by stemming them out on paper. Alter says that this setup provides a roadmap for research while also creating a record of the students’ thought process.

Exploring Creativity

One implementation of Project Zero’s tools is Alter’s Explore class, which is now in its fifth year.

In the class, students pursue and research any of their passions. Alter emphasizes that students are not bound by their academic or career interests in selecting a passion.

“It’s a class about self-discovery, advocacy and agency,” says Alter.

At the end of year, Alter hosts an Explore Fair where students can showcase their year-long projects.

Students’ project topics have included astrophotography, the theme of play and the originality of ideas.

Alter begins classes with creative warm-ups or challenges where students are given materials such as pipe cleaners or rubber bands and asked to create something that represents their current mental state. Alter believes that such activities encourage reflection.

“I like to create opportunities for students to think through ideas and let go of perfection,” he says.

Thinking Labs

Caleb Evans, Grandview Heights High School science teacher, joined a small book group five years ago, hoping its ideas on reflective learning would help him in his master’s research. Little did he know, the tools he learned from Project Zero would completely change his teaching style.

After discovering Project Zero, Evans is constantly looking for ways to improve as a teacher. Rather than keeping the same lesson plan every year, Evans is always revising.

In the classroom, he is particularly fond of Project Zero’s emphasis on reflection and visual thinking.

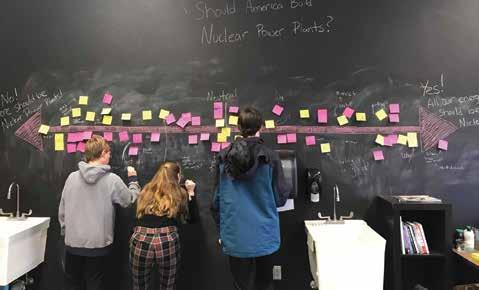

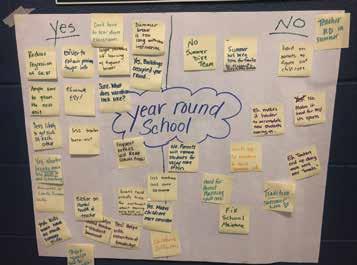

During a nuclear chemistry unit, students used visual thinking by placing their ideas on sticky notes. Other students could respond with their own sticky notes, and by the end of the unit, the students had learned more from each other than they would through individual research.

“Those were the best projects I’ve ever gotten,” says Evans.

He prefers hands-on projects over tests, as he believes projects provide more room to learn and reflect.

“We focus on the process over the product,” says Evans.

Evans allots time for journaling, when students can reflect on what they’ve learned and what they’ve struggled in. He takes away the students’ fear of failure by grading the reflection and thinking process rather than multiple tests.

“They can actually see their thought process throughout the span of weeks or months,” he says.

Evans applies this reflection method to his own teaching as well.

Students warm up for Alter’s Explore class with creative exercises like creating things out of pipe cleaners or rubber bands.

A student’s presentation of research at the Explore Fair.

“When a lesson (goes) wrong, I’ll address the class afterwards and (say), ‘Hey, this lesson failed. … Here’s why it’s on me and what we’re going to do next time to address it,’” he says.

Starting Young

While most of the teachers in Grandview using Project Zero tools work with high schoolers, Katie Konrad, a first-year third grade teacher, decided to take on the challenge.

Konrad first heard of Project Zero as a college student at The Ohio State University. She was interested in its ideas, so when she was hired by the Grandview Heights School District, she jumped at the opportunity to work with Project Zero.

Konrad appreciates how the initiative engages students in deep thinking even at a young age.

“You’re turning the kids into the holders of knowledge,” says Konrad. “You’re empowering them to wonder and to ask questions. … That makes them better lifelong learners.”

Konrad mainly uses two Project Zero methods. For the first, called “see, think, wonder,” Konrad asks her students to use all three of those processes when they are introduced to new concepts. She wants to find out what they already know and what they want to know.

When a student makes a claim, she asks them, “What makes you say that?” Through this Project Zero method, students learn to defend their reasoning early in their education.

“My goal is that when they are at home over the summer, they ask somebody, ‘Well, what makes you say that?’ or, ‘Why does that work?’” says Konrad. “(I want them to) continue that question asking in their own life.”

Konrad is grateful to work in a school district supportive of different learning styles.

“I’m glad that Grandview has a lot of really great leaders on board that are just trying to bring more of us into the Project Zero teaching style,” she says.

Students at the Explore Fair

Sarah Grace Smith is an editorial assistant. Feedback welcome at feedback@cityscenemediagroup.com.

- learn more about our special company WWW.DAVEFOX.COM | 614-459-7211

We’ll handle the details