8 minute read

Through the Lens

16 CivilWarNews.com April 2022

We Are Not Here For Plunder

“It looks like fate, twice Texas makes me a rebel.” – C.S. Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston

In March 1862, U.S. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s “Army of the Tennessee,” was preparing to attack Corinth, Miss., a major railroad hub and considered one of the two most essential places for the survival of the Confederacy. Grant was assembling his attack force at Pittsburgh Landing, Tenn., on the west bank of the Tennessee River. Gen. William T. Sherman assigned camp sites as the units arrived. The greenest soldiers, Sherman’s and Gen. Benjamin M. Prentiss’s Divisions were located on either side of a one room church named Shiloh.

At Corinth, incoming fresh troops were swiftly being formed into an army by Confederate generals Albert Sidney Johnston and P.G.T. Beauregard. Johnston knew his last opportunity to protect “the vertebrae of the Confederacy,” would be to attack the Federals while both sides had about an equal number of troops; that meant before U.S. Gen. Don Carlos Buell’s “Army of the Ohio” could reach Pittsburgh Landing.

Before the War, Johnston was highly regarded by both sides. His friend and West Point classmate, President Jefferson Davis, considered Johnston to be the greatest soldier in the country. Johnston rose from private to general in the Texas Revolution, served as Secretary of War for the Republic of Texas, fought in the Mexican American War, and on April 9, 1861, resigned his post as the U.S. Commander of the Pacific in California.

In June, Johnston left his young family in Los Angeles, Calif., to join the Confederacy. Both sides were fascinated as 59-yearold Johnston “plunged into the desert” on horseback, avoiding the gauntlet of Federals looking for him during the hot summer months. Johnston’s safe arrival in Richmond, Va., was greeted with joy across the South, and he was assigned command of the Western Military Department.

It took three days for Johnston to move his 40,000 men the 23 miles from Corinth to Shiloh due to a heavy rainstorm. Keeping noise to a minimum was another issue. The men whooped when they spotted a deer; soldiers fired guns to check if their gunpowder was too wet, bugles sounded, and men yelled. At the evening conference of the generals, Beauregard vigorously recommended calling off the battle. The Confederates had lost the element of surprise and the men had already eaten their rations.

Johnston listened to Beauregard’s concerns. He reasoned that if the Federals were aware of the Confederates’ presence they would have already attacked, and the men could eat the Union supplies. He decided to attack at daylight. Johnston told an aide, “I would fight them if they were a million,” adding, “I intend to hammer ‘em!” On his return, Beauregard discovered that the drumming he had ordered silenced came from the Federal camp. The lines between the belligerents were closer than he realized.

The Federals, perhaps believing the Confederates would stay in place, waiting to be attacked, had been ignoring reports of Confederate activity. Former Chief Engineer of the Memphis & Ohio railroad, U.S. Col. Everest Peabody, 25th Mo., “thought we were lying in the face of a powerful enemy, in a very careless and unguarded position, liable to be surprised and overwhelmed at any time. … instead of lying idle, as we were at that time, we ought to put ourselves in some condition to resist an attack, in case one should be made by Johnston, and which was liable to happen at any time.”

The Battle of Shiloh, Tenn., April 6-7, 1862, began before dawn. Peabody, unwilling “to be taken by surprise,” sent out a reconnaissance force of 300 men. Maj. James Powell was ordered that, if he encountered the enemy, he was to “drive in the guard and open up on the reserve, develop the force, hold the ground as long as possible, then fall back.” Powell encountered C.S. Maj. Aaron B. Hardcastle’s 3rd Miss. Infantry Battalion. The sound of firing alerted the Federals. Prentiss angrily rode up to Peabody telling him, “Colonel Peabody, I will hold you personally responsible for bringing on this engagement.” Peabody responded that he was always responsible for his actions and galloped off to lead his brigade, interrupting the Confederate timetable.

Earlier, Johnston had telegraphed his attack plan to Davis: [Leonidas] Polk the left, [Braxton] Bragg the center, [William J.] Hardee the right, [John C.] Breckinridge in reserve. Beauregard was promoting a complicated plan to send the troops in three waves. A clear agreement of the battle plan wasn’t made. Before sunup, Beauregard was continuing to advocate canceling the assault until musketry was heard. “The battle has opened, gentlemen,” said Johnston. “It is too late to change our dispositions.”

Johnston, aware that he had brought the smaller army into the area previously agreed as Beauregard’s, was “unwilling that a subordinate should suffer by his arrival.” He graciously assigned the commanding position, directing the troops forward from the army’s rear to Beauregard. Beauregard misinterpreted the gesture as giving him carte blanche. Johnston believed his plan would be followed, he would be supported and decided to ride at the front with the men, more like a brigade or division commander. As he rode off towards the fighting, Johnston turned in the saddle and spoke to his staff, “Tonight we will water our horses in the Tennessee River.”

The Confederate advance wavered as men entered the Federal camp and ate the prepared breakfast. Curious men explored the tents, read letters “to find out what northern girls were like,” and collected souvenirs. Johnston rode in to redirect the men. Having hurt the feelings of a souvenir hunter by admonishing, “We are not here for plunder.” Johnston took a tin cup off a table

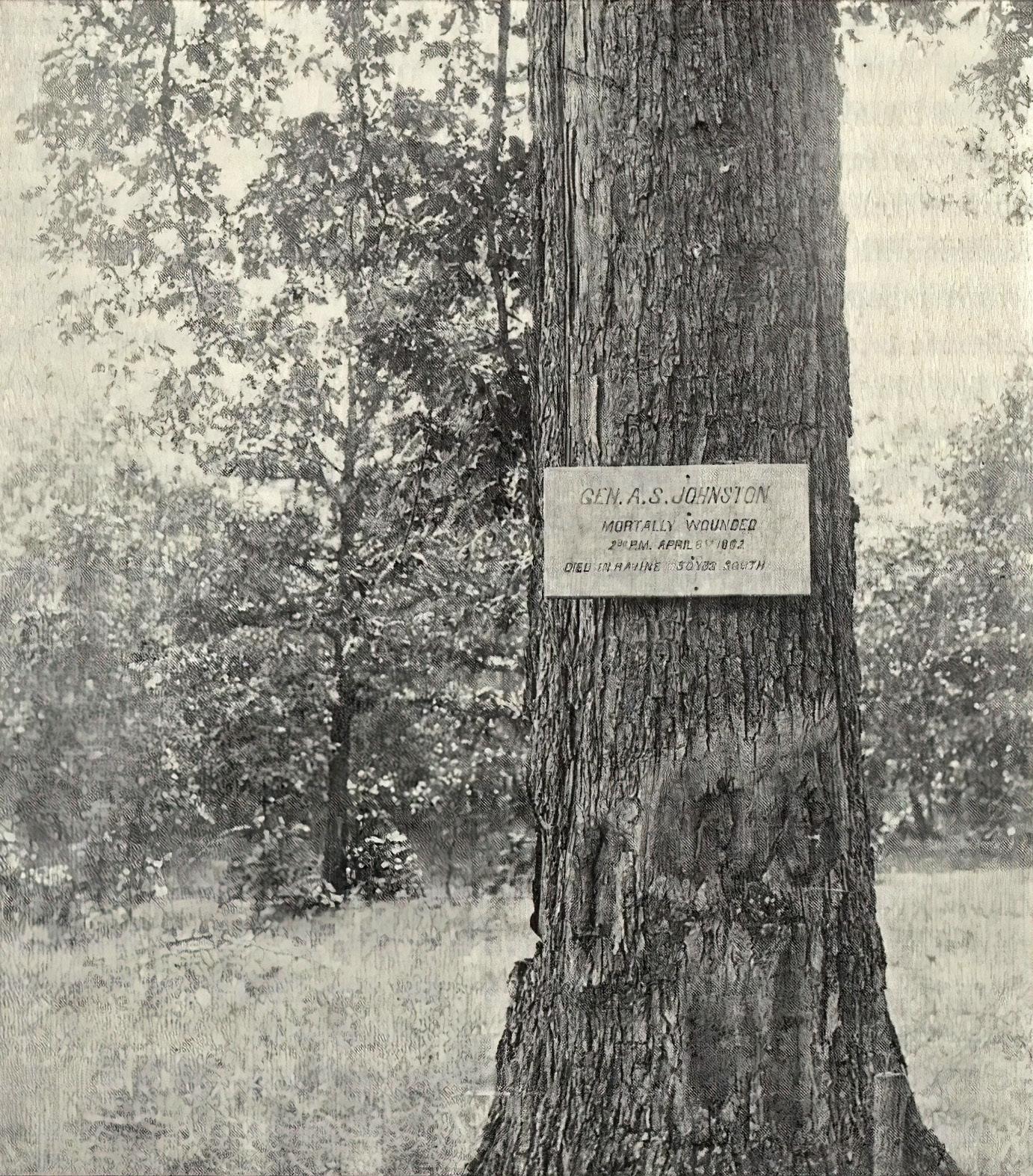

United States Senator Isham G. Harris, revisited the Shiloh battlefield in April 1896, for the express purpose of locating the spot where Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston had been mortally wounded on April 6, 1862. A sign was put on the tree that read: Gen. A.S. Johnston Mortally Wounded 2:00 p.m. April 6th 1862 Died in Ravine 50 yds South Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston. Colorization © 2022 civilwarincolor.com. Courtesy civilwarincolor.com/cwn. (Public Domain)

April 2022 CivilWarNews.com

General Albert Sidney Johnston monument on the Shiloh Battlefield. The plaque reads:

C. S. General Albert Sidney Johnston Commanding the Confederate Army, Was mortally wounded at 2.30 P.M.,April 6, 1862, Died in ravine, 50 yards south-east, at 2:45 P.M.

The monument features an upright U.S. 30-pdr. Parrott rifle. Visible on the right rimbase is the foundry number 666, matching to registry number 183. The rifle was produced in 1863, by West Point Foundry, and weighs 4,240 pounds. (Jack W. Melton Jr.)

Gravesite of Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston at the Texas State Cemetery in Austin, Texas. (Library of Congress, Highsmith, Carol M., photographer.) The tree stump in 2001. (Jack W. Melton Jr.)

States: D. Appleton, 1879. ✸ Neal, W.A. Dr. Illustrated history of the Missouri Engineer and the 25th Infantry Regiments:

Donohue and Henneberry, 1889.

Stephanie Hagiwara is the editor for Civil War in Color.com and Civil War in 3D.com. She also writes a weekly column for History in Full Color.com that covers stories of photographs of historical interest from the 1850’s to the present. Her articles can be found on Facebook, Tumblr and Pinterest.

stating, “Let this be my share of the spoils today,” and used it instead of a sword to direct the battle.

Breckinridge’s men were reeling from the Federal guns planted in the ten-acre peach orchard in full bloom. “We must use the bayonet,” Johnston said as he rode by, touching the tips of the bayonets with the tin cup. Still the men were hesitant. Johnston went out front in the center ahead of the men, stood in his stirrups, and called, “I will lead you!” On his thoroughbred, “Fire-eater,” Johnston led a charge into the sheet of flame and raining pink blossoms, driving the Federals.

Afterward, Johnston was grinning, proclaiming “they came very near to putting me hors de combat in that charge.” He showed off his boot sole dangling from the toe; his uniform was nicked as well. Alas, soon Johnston was wobbling in the saddle, his femoral artery had been cut. The tourniquet in his pocket could have saved him but Johnston’s personal physician was caring for wounded elsewhere and no one knew how to use it.

Johnston was the highest ranking general on both sides to die in the war. According to Davis, “When Sidney Johnston fell, it was the turning point of our fate; for we had no other hand to take up his work in the West.”

– MAKER –LEATHER WORKS

WWW. DELLSLEATHERWORKS.COM

Sources:

✸ Nevin, David, and the Editors of Time-Life Books. The Road to Shiloh: Early Battles in the

West: Alexandria, VA, 1983. ✸ Foote, Shelby. The Civil War:

A Narrative: Volume 1: Fort

Sumter to Perryville: Vintage

Books Edition, 1986. ✸ Johnston, William Preston.

The life of Gen. Albert Sidney

Johnston, embracing his services in the armies of the

United States, the republic of

Texas, and the Confederate

Tim Prince

College Hill Arsenal PO Box 178204 Nashville, TN 37217 615-972-2418