7 minute read

The Summer of '72: Clarkson Vehicle Design Team Recalls Innovation, Dedication — and a Whole Lotta Beer Cans

By Jake Newman

It has been a half-century since Clarkson’s Urban Vehicle Design Competition (UVDC) entry drew national attention. Driven by a shared passion for cars and fueled by community support, a team of undergraduate engineering students met the challenge head-on.

Advertisement

In August 1972, the UVDC judged vehicles developed by students across the U.S. and Canada to be low-emission, safe urban vehicles. After weeklong testing at the General Motors

Proving Ground in Michigan, Clarkson’s design finished in the top 10 of more than 70 vehicles while relying on a fraction of the budget of its competitors.

Six members of the Class of 1972 — ED CICHANOWICZ, STAN KUJAWSKI, HERB HELBIG, THRUSTON AWALT, DAVE COX and EVERETT “BUZZ” GRANGER — formed the core of Clarkson’s team for the competition.

“We were a small but dedicated team focused on building a car with unique safety features and improved emission control systems,” Helbig recalls. “Our small size required that everyone pitched in to do whatever was required.”

A year before the competition, Cichanowicz remembers the symposium for prospective teams, held at the University of Toronto, as intimidating.

“We came up, and there were a lot of schools with fancy graphics and showing a lot of swagger — and Stan and I didn’t,” Cichanowicz says. “Some of these teams found that talking about building a car and actually doing so are very different; many never delivered a vehicle to the Proving Ground for trials the following year.”

Community Connections

As the project took shape, the group’s energy was matched and supported by devoted Clarkson faculty and staff. Mechanical engineering professors Ken Saczalski and Richard Wirtz advised on the design of the energy-absorbing frame and emissions control technologies. Perhaps of greater value were Ray Smith, a machinist, and electrician Carl Stevens. They were instrumental not only in vehicle construction but also in using their Potsdam network to source parts and services.

According to Cichanowicz, Smith and Stevens secured contributions from local businesses that included material for the vehicle mockup and professional welding and fabrication services for the frame. The team roughed out the body skin in a wing of Old Main, but a professional body shop in Massena donated materials, services and the use of specialized power tools and shop space.

Article from The New York Times, July 15, 1972

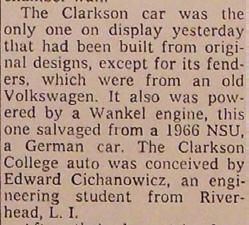

The team located a rare NSU Spider — one of only a few vehicles powered by a Wankel engine — in a nearby salvage yard and received the engine and drivetrain as donations. The front suspension was also donated, repurposed from an MGB sports car. A local paint shop offered materials and services to cloak the vehicle in Clarkson gold.

“We learned how a small, dedicated group of engineers could accomplish great things by having a can-do attitude,” says Helbig. “We didn’t have a lot of money or a big staff, but we were resourceful and didn’t understand the meaning of the word ‘can’t.’”

Built With Innovation

Indeed, “can’t” was a word the group heard throughout their build. The group relied on innovation and effort to bypass impossibility, particularly when working with the seemingly random assortment of parts cobbled together for their build.

“Scratch building a car from scavenged and donated parts created design problems. One example was coaxing a V8 electronic ignition system to work on a Wankel engine, something its manufacturer, Motorola, said ‘couldn’t be done,’” says Awalt. (Following the competition, Motorola recognized this feat and reached out to hire Kujawski and Cox.)

One significant expenditure was for passenger seats with unique features, intended to earn high scores for safety. Due to their high cost, justified to earn valuable points, the team couldn’t order the second seat until they secured the funds. The second seat arrived just in time before the team left for Michigan, thanks to the Herculean efforts of a Watertown delivery driver. “He volunteered to bring the seat on a Friday night,” says Cichanowicz, laughing. “He strapped it to the roof of his car on his way to take his family on a camping vacation.”

But it wasn’t the expensive seats that garnered the attention of the national media during the tests in Michigan at the Proving Ground. In fact, it was one of the least expensive features — albeit the most innovative — of the vehicle that landed the Clarkson students on a brief ABC News feature: the beer-can bumper.

The beer can bumper

The bumper lacked a façade to cover its energyabsorbing devices. When it became apparent that Clarkson’s car had repurposed Pabst Blue Ribbon cans as part of its bumper, the cameras went wild.

“The Alcoa plant in Massena provided us with partially finished cans,” Cichanowicz remembers. “One end looked like a normal can, but the other end was unfinished with the right curvature to collapse in a manner that absorbed the most energy.”

Thanks to the support of the North Country and the innovative Clarkson spirit, the team’s submission placed seventh out of 72 vehicles and cost just a fraction of the other top-performing cars. While the winning build from The University of British Columbia came in at $35,000, Clarkson’s cost less than $5,000.

Long-Lasting Legacy

Clarkson students continue to learn how to do more with less — and come out on top. Project teams similar to the UVDC group exist in a much more robust fashion at Clarkson today, as students from all educational disciplines represent the University as part of more than a dozen Student Projects for Engineering Experience and Design (SPEED) teams. The UVDC team, in some ways a precursor to today’s SPEED teams, benefited in much the same way: by gaining hands-on experience that prepares them for life after Clarkson.

—ED CICHANOWICZ ’72

“Half a century later, it’s impossible to deny the role that Clarkson and the UVDC project had on what was a long and rewarding career in automotive powertrain electronics,” says Cox. “From early ignition systems to complex engine control computers, capture. Awalt, who designed much of the digital dashboard, settled in Silicon Valley for a career dedicated to integrated circuits.

Helbig became the project lead on the Chrysler team that developed the Dodge Viper. Kujawski, who artfully shaped the vehicle from repurposed fenders and aluminum panels, initially started at Motorola with Cox but eventually established his own product design firm.

“The UVDC provided me an opportunity to exercise my desire to be an automotive designer,” says Kujawski.

“While Detroit never came into play beyond this project, the experience helped me realize I was interested as much in aesthetics as performance.” integrated circuit accelerometers and gyroscopes and electric vehicles, it was a very interesting time to be in the industry.”

Cichanowicz believes the event highlighted the potential to advance automotive innovation.

“The national attention on the UVDC contributed to the debate in the 1970s over safety and environmental controls, which by decade’s end saw further safety mandates, and, in 1977, amendments to the Clean Air Act lowering tailpipe emissions,” he says.

While the UVDC project challenged team members, provided a springboard for careers and showcased advances in technology, Clarkson’s team members believe the big win was the camaraderie of a school and a community providing solutions to a problem at the highest level.

Each project member leveraged the UVDC experience to launch their career. Cichanowicz, responsible for the vehicle’s emissions control system, devoted his career to developing environmental control technologies for fossil power plants to address acid rain, and, today, he contemplates CO2

“A renowned Clarkson legacy is that one in five alumni become accomplished entrepreneurs, business owners or senior managers — a feat achieved by almost the entire UVDC team,” adds Cichanowicz. “The takeaway for students? Get on a project team. Now.”