7 minute read

Undercover Heroes @ APSU

By Tony Centonze

APSU's GIS (Geographic Information Systems) office has been quietly going about its business for more than two decades, always providing great services to our community, but never receiving much fanfare. Then came the pandemic.

“We are part of APSU, but our center is a stand-alone unit,” GIS Director Mike Wilson said. “We do a lot of work in the community for various city and county governmental departments. We work with firstresponders, and manage the Montgomery County 911 Center's data. We've also worked on various disaster relief efforts with the city and county. After the last tornado, we put together an app to speed damage assessment. Doug Catellier is our project manager. He spends a lot of time flying drones and making maps.”

The GIS office normally operates with six full-time staff, and approximately ten to twelve students. Currently, the office has an additional ten to fifteen people working on a very special Covid-19 related project, making 3D printed face shields for medical personnel, and others working on the frontlines of this world-wide crisis.

“This is our priority now, but we're still maintaining our GIS work with local agencies,” Wilson said. “We are very well known to city and county agencies, but the general public doesn't really know what we do. We've found ourselves in the media spotlight a lot more in recent years.”

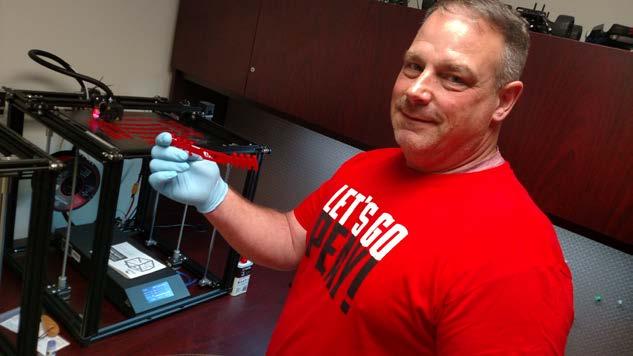

GIS Director Mike Wilson

In 2008, Catellier did extensive work related to Kentucky's Wolf Creek Dam. “Wanting to understand the effects of a possible dam burst in Kentucky, we helped local officials build models to predict how the flooding might occur,” Catellier said. “Fast-forward to the actual flood of 2010, our models were pretty accurate. We ended up working extensively with EMA (Emergency Management Agency), doing damage assessments. We personally helped capture a lot of data.”

Doug Catellier

Wilson's GIS office actually acquired its first 3D printers just two or three years ago. “The university gives us latitude on what we can purchase, as long as the center is paying for itself,” Wilson said. “We got 3D printers at the same time a grant came through for a drone. These printers can get pricey. Our first one was about $1,500. At first, we were just making attachments for our drones. One of our students had a $200 printer that was as capable and flexible as ours. So, we ended up adding a second printer to our arsenal.

“This current project kicked off around March 19,” Wilson said. “APSU's General Scott Brower was appointed to the Governor's Coronavirus Task Force. He called and said, 'can you meet me in ten minutes? The state wants to know if we can print any medical equipment.' I said, funny you should ask, we just started researching that earlier this week.

“I told Mike Hunter, start looking around before General Brower gets here. Let's see what's out there, and who is already having some success. In General Brower's meeting they had highlighted the need for masks, face shields, etc. Face shields were among the items Hunter had already identified as something of interest. He investigated, and found a model that was popular overseas. General Brower said, 'let's see what we can do'. That was late morning. Within three hours we pulled our first one off the printer.”

For this process, a roll of plastic wire is fed through, heated and melted. 3D printers utilize an additive manufacturing process to build the product, so there is virually no waste.

“There are three main components, the frame, an acetate sheet, and an elastic band,” Wilson said. “It still takes about three hours to make one on this particular printer. Some of the other printers are slightly faster. The frame and elastic are the easy parts. The hard part is the sheet of acetate. It's a 12” x 12” sheet that has to be cut. A complete set up is one frame, one elastic band, and 10 sheets of acetate.” Wilson says, this way, the end user can determine how often they want to replace the shield. The frame is reusable, and can be easily cleaned. The acetate is meant to be thrown away. The sheets are cut with a rounded bottom, and four holes that allow easy attachment to the frame.

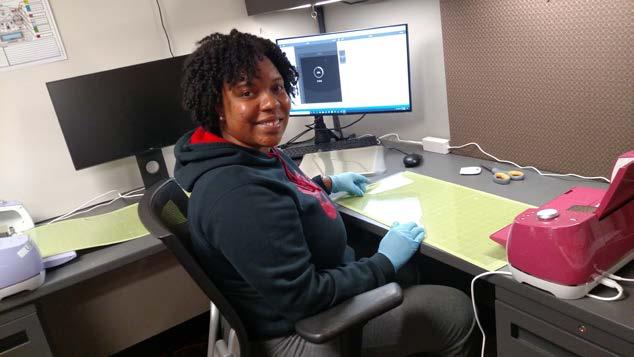

Shemekia O'Neal

“We started with Cricut cutting machines,” Wilson said. “Two machines would get us between 40 and 60 sheets per hour. The state wants 10,000 frames, so that's 100,000 sheets of acetate. Luckily, we are part of a state coalition. We have other locations making frames and shipping them to us, but we are finishing everything here.”

Rachael Perkins

Several other Tennessee universities are printing and sending frames. Wilson and his team are doing most of the acetate cutting, attaching of elastic bands, and final assembly. At the time of the interview, 102 boxes had been shipped. Each box contained 36 frames, 36 elastic bands, and 360 face shields. All are sent to TEMA (Tennessee Emergency Management Agency), the agency in charge of getting the product to the medical facilities that need them most.

Toya Jones

“We tried not to reinvent the wheel,” Wilson said. We found an open-source design that was being used successfully. The cost per unit is probably around $1. This office is a non-profit, so our main cost is labor. THEC (Tennessee Higher Education Commission) is working with TEMA and the state to supply all the materials. We have however bought some additional equipment to ramp up production.” Wilson says the student response has been great. “They are highly motivated and excited to get involved. Initially, I had to put the word out, but after the first couple signed up, others heard and wanted to get involved. We tried to hire friends and family members of those students, to help limit exposure.” “I know some Physician's Assistants and Nurses, and I hear from them how grateful they are,” Catellier said. “I didn't know how important these face shields were at first, but one of the medical professionals told me that wearing them extends the life of their masks, and those are hard to get right now. So, that's a big positive. “I want stories to get out there about people taking positive action to help the community,” Wilson said. “We are in a position to do something that helps, but for most people, the best thing they can do is stay home and watch their favorite streaming service. We all have a part to play.”

Brandi Miller

Wilson and Catellier haven't gotten any feedback directly from end users. Nor have they heard much back from TEMA.

“Some of our resources have been used bylocal folks,” Wilson said. “Feedback from them has been positive. They say our products are helping out a lot. We want to help as much as possible. We looked at operating 24 hours a day, but that wasn't feasible, so we've been running two shifts for a total of 16 hours a day.

Mason Cordell

“Our quota from the state is four boxes a day, but we're now able to produce about ten boxes a day since we added laser cutters. The Cricuts can cut 60 an hour, the lasers are way quicker. They've asked us to continue until May 31. TEMA wants 10,000 to 15,000 face shields in total, so we'll keep this going as long as it's needed.”

The immediate and long-term importance of this moment is not lost on Wilson and Catellier.

“This center has always tried to step up during an emergency,” Wilson said. “I believe strongly that one, we have to help our community. We are citizens of Clarksville, Montgomery County, Tennessee, so we have to help. And two, the students that work here have to see leaders stepping up in a time of crisis. It's important to see us as good mentors, trying to go above and beyond, helping out and doing the right thing. We hope they will continue that legacy when they are in the workforce.”