13 minute read

THE DIGITAL AGE HAS ITS OWN MANTRA FOR CAREER SUCCESS: CHANGE OR DIE

Radio Shorts

MYTHS, LEGENDS AND OBSCURE FACTS FROM 100 YEARS OF RADIO

Advertisement

____ by Crystal Hammon

RADIO’S FIRST CULTURE WAR At the beginning of 1920, there were no radio stations. Two years later there were roughly 600. In the early days of radio, nearly everything on the airwaves was experimental. Skirmishes over purpose and content were rampant. Some people, for example, considered classical music on the radio a possible answer to America’s labor problems. If everyone listened to Bach and Beethoven, some thought Americans might live in perfect harmony without labor strikes, racial strife or class warfare. “Among the upper bourgeoisie in the early 20th century, [there was a belief that] the spread of ‘good music’ equaled the spread of moral and political goodness— that initiatives of cultural uplift could counteract vice and criminality, promote temperance and chastity, pacify class antagonism, neutralize labor unionism and hasten the integration of unassimilated immigrant groups into the AngloProtestant mainstream,” writes Cliff Doerksen, journalist, historian and author of American Babel: Rogue Radio Broadcasters of the Jazz Age.

WOMEN IN RADIO The first woman radio DJ in Indianapolis was Gwendolyn Schort Burris, a private drama teacher and Butler University graduate who was invited in 1937 to co-host Tea Time Tunes, a radio program at WFBM—the ancestor of WRTV. “In those days, women just did not do anything,” Burris said in a 1977 interview. “I just couldn’t believe it. Here I was, a little nobody, and yet I was going to become a radio personality.” Burris went on to host Apron Strings and Wishing Well, radio shows that targeted women. Wishing Well was sponsored by Kittle’s Furniture. “The thing that we tried to do was entice the listening audience to [go in and pick up] a contest blank and wish for something,” Burris said. “Wishes came true each week because the company would have me read the letters they selected.”

RADIO FACT & FICTION Practically everyone knows about The War of the Worlds, the famous Orson Welles radio drama from the Golden Age. Two things you might not know about that broadcast: 1.

2.

For decades, a myth circulated that the show caused widespread hysteria. American newspapers started that legend. They were so threatened by radio’s growing advertising revenues that they jumped at the chance to discredit radio as a credible news source by exaggerating the show’s effect.

The radio waves from the original 1938 broadcast of The War of the Worlds are not dead. They’re traveling in space a mere 80 light years away. That’s because sound waves travel at the speed of light— forever. ■

INDIANA HISTORICAL SOCIETY, M0614

Maestro of Peace

FORMER ISO CONDUCTOR PROMOTED RECONCILIATION AFTER WORLD WAR II ____

by Kyle Long

As the conductor for the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra (ISO) from 1937 to 1955, Fabien Sevitzky is widely credited for bringing the ISO to national prominence, in part because he understood the importance of mass media in establishing the orchestra’s reputation. He secured important recording and broadcasting opportunities for the ISO and believed that radio could be harnessed for the greater good, as revealed by one of the maestro’s finest moments near the end of his ISO career.

Fabien Sevitzky was born Fabien Koussevitzky in Vyshny Volochyok, Russia in 1891. Sevitzky shortened his family surname at the request of his uncle Serge Koussevitzky, the famed conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The elder Koussevitzky was understandably concerned about the potential for confusion between the two identically named maestros. Throughout his career, Sevitzky lived in shadow of his venerated uncle, but his contributions to classical music are unforgettable. Decades before the concept of diversity entered the national dialogue, Sevitzky realized that classical music was in need of greater cultural representation. During the Jim Crow era, Sevitzky’s ISO featured black guest soloists, performed at Crispus Attucks High School and forged relationships with Ruth McArthur’s Indiana Avenue conservatory. Sevitzky countered the near-monopoly of European and Russian composers in the concert hall by championing the work of new voices from across the Americas and the Far East. He was an ardent supporter of the trailblazing black composer William Grant Still, commissioning work from Still and conducting the premiere of Still’s 1960 opera, Highway 1, U.S.A. Sevitzky also played a role in bringing the work of South American composer Astor Piazzolla to international attention. In 1953 Sevitzky traveled to Argentina to conduct Piazzolla’s symphonic work Buenos Aires and awarded the composer a scholarship to study music in Paris with Nadia Boulanger. In April of 1954 Sevitzky programmed Buenos Aires on an ISO bill, marking the first major U.S. performance of the Argentinian master’s work. Today Piazzolla is remembered as the king of tango, and his music is celebrated around the world. One of Sevitzky’s most interesting artistic relationships featured the Japanese composer Akira Ifukube. In 1936 Sevitzky conducted the world premiere of Ifukube’s Japanese Rhapsody with the Boston People’s Symphony Orchestra. The young composer was so grateful to Sevitzky that he later dedicated the piece to the maestro. So began an enduring long-distance correspondence between Sevitzky and Ifukube that would survive the tumultuous period of Japanese and American hostilities during World War II.

There is relatively little scholarship on Sevitzky’s life, but one thing is clear: the maestro believed deeply in music’s power to influence social change. Sevitzky also believed music could be used to incite war. Horrified by the nightmarish reports of Nazi war crimes emerging from the Second World War, Sevitzky generated national controversy in July of 1945 with a series of sensational remarks connecting German music to the rise of Nazism.

If music could be used to start war, Sevitzky believed it could also inspire goodwill and peace among nations. In that spirit, Sevitzky summoned the compositional talent of his old friend Akira Ifukube to plan what would become the most dramatic musical gesture of his tenure with the ISO.

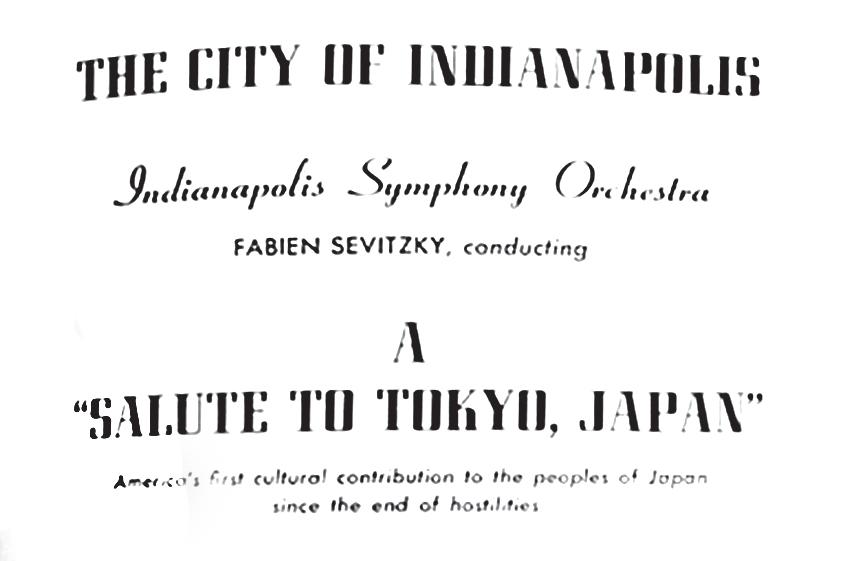

Ifukube had promised Sevitzky the debut performance of his Sinfonia Tapkaara. Sevitzky seized the opportunity to construct a program that would function as a musical olive branch to Japan. Sevitzky’s premiere of Ifukube’s symphony was scheduled for January 26, 1955 at the Murat Theater, just ten years after the United States’ cataclysmic detonation of atomic weapons in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The concert was titled A Salute to Tokyo, Japan and ambitiously billed as ”America’s first cultural contribution to the people of Japan since the end of hostilities.” A commission to score a rather odd Japanese film, depicting the psychological terror of wartime Japan interrupted Ifukube’s completion of Sinfonia Tapkaara. Godzilla premiered in Nagoya, Japan in October of 1954. The film’s iconic title character represented a metaphor on the dangers of nuclear weaponry and reflected the atomic destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The ominous brass motif Ifukube created for Godzilla is one of the most famous themes in international cinema and remains the composer’s best-known work. It’s unclear if Sevitzky was aware that record numbers of Japanese moviegoers were experiencing Ifukube’s music in 1955 as they packed theaters to marvel at the awesome spectacle of Godzilla. The maestro wasn’t content with his Tokyo tribute being confined to Indianapolis. With the assistance of Indy’s long running AM powerhouse, WIRE, Sevitzky recorded the concert and planned its broadcast in Japan. Immediately after the concert, a recording was flown to Japan and “broadcast over 61 Japanese stations to a potential audience of more than 3,000,000 persons,” according to a January 26, 1955 report in The Indianapolis Star. There are no available English language records of the Japanese response to Sevitzky’s broadcast of international goodwill. In fact, there’s very little record of his gesture at all. Nevertheless, his message of civility and peace calls out to listeners today as an enduring beacon of hope. ■

Music Imitates Nature

AN ORIGINAL COMPOSITION CELEBRATES INDIANA’S NATURAL WONDERS ____

by Eric Salazar & Anna Pranger Sleppy

Nature is mystifying and beautiful. The calls of a bird or shades of color on a flower surround us, yet often go unnoticed. In celebration of nature’s majesty, Classical Music Indy partnered with Indiana’s Fort Harrison State Park to draw attention to the wonders of Indiana’s locale. The idea: create the first-ever classical composition that pays tribute to the unique natural assets of one of Indiana’s most beloved state parks, and present the music in a concert series. Thanks to the Indiana Arts Commission’s Arts in the Parks and Historic Sites program, Classical Music Indy commissioned local composer Rob Funkhouser to write this new piece, which premiered at the park on April 28. Funkhouser is “a composer, performer and instrument builder who can never quite sit still.” The Butler graduate has released recordings on various music labels in three countries and maintains an active career as a performer in central Indiana. In addition to the Fort Harrison commission, his recent projects include music for Parade 2017, a dance choreographed by Rebecca Pappas and facilitated by No Exit Performance, as well as a new work for Forward Motion, a local ensemble.

Funkhouser’s Three Peacetime Images for Fort Benjamin Harrison State Park tells the story of the park’s creatures in three movements. In the first movement, percussion instruments imitate woodpeckers with varying rhythmic patterns, ranging from steady to sporadic. The second movement’s melodicas and alto saxophone stand in for frogs croaking in the night. As a finale, Funkhouser raids the collection of Rhythm! Discovery Center, incorporating one-of-a-kind “plank marimba” to evoke the visual excitement of lightning bugs through the audible sensation of mallets on wood.

A local trio of percussion and saxophone artists will perform the piece live on Saturday, September 22 at 2 p.m. at Fort Harrison State Park. The performance is free, but the park has an entrance fee per vehicle. More information can be found on Classical Music Indy’s Facebook Event page. ■

This activity is made possible with support by the Indiana Arts Commission, the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, and Fort Harrison State Park.

A Viola Plays in Baghdad

by Burton Runyan

Bloomington violist Dena El Saffar grew up surrounded by Arabic music, but it wasn’t until she visited Iraq that she finally understood it.

When she was 17, the Iran-Iraq war had ended, and she was able to accompany her father on her first trip to visit family in the capital city of Baghdad. “I’ve reflected back so much on that trip,” she says. “There was a lot of build up, wanting to go—it started really young for me.” It was the perfect age to appreciate the journey. “At that age, you really start to become more self-aware. Asking yourself, ‘Who am I compared to my peers?’ I wanted to be an individual and to know my roots instead of being like everyone else.” El Saffar is glad she made the trip when she did. Shortly after her return, the Gulf War erupted, followed by a series of conflicts that still impact the region. “It was as if I had a premonition I may never be able to go back, because I told myself, ‘I’m going to absorb every experience, every landscape, every building.’ I don’t think I’d felt that way about anything before. I think that awareness deepened my experience there.” Her age also afforded another moment of serendipity. Growing up in the suburbs of Chicago, El Saffar was an accomplished violist. She was preparing to go to conservatory to study classical music and brought her viola on the trip to stay in practice. When El Saffar’s cousins asked her to play along with an Iraqi pop song, she obliged, and their excitement set her life on a new course. “I had been playing very serious, classical things. And as soon as I started playing [with my cousins] it was like a big dance party,” El Saffar says. “I don’t think anyone had really danced to my viola music before. That was a pivotal moment for me.” After returning from Iraq, El Saffar formed the Bloomington-based band, Salaam. Today, they get radio airplay, take interviews with National Public Radio and play for crowds at festivals, pop-up concerts and private parties across the country. “My favorite situation is playing for a mixed audience,” she says, describing the cultural interactions that happen when Hoosiers hear her perform a classical vocal tradition that has been around for centuries—the Iraqi maqam. Americans tend to be very circumspect and stoic—even meditating—whereas people from the Middle East clap and dance, which brings about a fun realization for Americans who haven’t experienced the music as it’s played on the streets of Baghdad. “It’s such a loosening up, and I love that because that’s the kind of cultural interaction I love to create. It’s humanizing, which is what we all need right now.” That trip to Iraq helped El Saffar connect to her family roots and introduced her to a new genre of music, showing her how music can bring people together across boundaries. “One of the things that has stayed with me is the soundscape in Baghdad,” she says. “All the different mosques broadcast the call to prayer at the same time. It sort of clashes in a really great way. You hear the near ones and the far ones, and they’re all in different keys and voices.” El Saffar found beauty in classical music and discovered humanity on the streets of Baghdad. Today, she brings the two together in the heart of the Midwest. ■

MUSIC AND DANCE: Greater than the Sum of Two Parts

by Chantal Incandela

THE ENERGY BETWEEN A DANCER AND AN AUDIENCE CAN BE A POTENT, PALPABLE THING.

Often we hear of artists “feeding off” the energy of an appreciative audience and vice versa. Add the energy between a musician and dancer, and you get an extra element of excitement for performers and audience alike.

“We dance to canned music most of the time,” explains Mariel Greenlee, dancer with Dance Kaleidoscope, describing the relationship dancers have with prerecorded music. “It feels like a conversation. And when you add another person to the mix, it feels a little more alive. It makes the music seem like a living, breathing thing that you dance with like a partner.” Helping her create this connection in October is the music of George Gershwin and Claude Debussy in Music of the Night, played by Eric Zuber, a 2013 American Pianist Association finalist. Each artist views the collaboration through a distinct lens. Zuber, who has a special relationship with Gershwin’s music, has collaborated with other musicians before, but never with a solo dancer. Nevertheless, he appreciates what it will bring about. “Participating in a multi-disciplinary collaboration like this can really expand one’s horizons and change the way one thinks about music,” Zuber says. “Working with and studying the movement of dancers, instrumentalists can gain a number of insights into musical flow, phrasing and other such important elements that can benefit our interpretations of solo music. I’ve always enjoyed the process of creating something special together in a spontaneous way.” Now in her 14th season with Dance Kaleidoscope, Greenlee has danced to this repertoire before, but never accompanied by a live musician. She finds the collaboration with Zuber easy, fun and exciting. “In dance, you’re in a hyperactive listening frame of mind,” she says. “You’re also hyperaware of your body, which is your instrument. Things happen, and you’re like ‘Oops, I accidentally balanced that in a way I haven’t before, but then I was late. But then he sped up and I sped up, and we were together, and it was a magical.’” There’s a hyperawareness for Zuber as well. “When working with dancers, I expect it to be more akin to solo playing, but that doesn’t mean I’m not going to have my attention fixed constantly on how I can musically assist what the dancer is attempting to convey on stage,” he says. Greenlee describes her role as dancer as “the physical embodiment of music.” She feels closely connected to all music—especially when it comes from a live artist. “These moments can’t be forced,” she says. “They only happen as two living, breathing things together. It’s magic.” ■

For Music of the Night performance and ticket information, visit Dance Kaleidoscope’s website at www.dancekal.org.